Chapter 2.

IMPERATOR ANDRONICUS KOMNIN OF THE XII CENTURY - IT IS JESUS CHRIST DURING HIS PRESENCE IN TSAR-GRAD OF THE XII CENTURY.

41. THE REPETITIONS OF ANDRONICUS’ STORY IN NICETAS CHONIATES’ MANUSCRIPT.

41.1. ‘THE TWO KINGS’ ALEXIUS COMNENUS – A REPETITION IN CHONIATES’ ‘HISTORIA’.

We have repeatedly noted that the text by Nicetas Choniates which we have today is by no means an ancient original, but a rather recent compiled work, however undoubtedly based on the original sources. The editor – compiler ‘Choniates’ by no means always understood the meaning of the chronicles he was processing. You can tell from the numerous unclear passages in his ‘Historia’. Only now, having understood what it’s actually all about, we in many cases are able to reconstruct the real picture.

In particular, having told the story of Andronicus-Christ in detail, Nicetas Choniates on several occasions returns to it, but in a much more concise way and using different names.

The matter of the fact is as follows. Prior to Andronicus there was reigning Alixius Comnenus, the son of Emperor Manuel. Choniates claims that the young Alexius was strangled by Andronicus, and effectively disappeared from the historical stage [140]. However, some time later Alexius Comnenus reappears on the pages of Choniates’ ‘Historia’. In order to make both ends meet, Choniates has to call this ‘new Alexius’ an imposter, ‘looking phenomenally alike’ the murdered young Alexius. ‘Thus, an imposter, who called himself the son of the Roman emperor Manuel Comnenus, played his role so artfully and so craftily simulated the appearance of the deceased King Alexius, that he resembled him even in the style and golden colour of his hair and he also stammered in the same way the late young king did… He was able to lure Sultan Arslan and several other Turks ... so that in a short time assembled an army of 8,000 men willing to follow him anywhere. With these forces he marched on to the cities in the valley of the Maeander River: some of them capitulated; the other, which put up resistance were brought by him to the most disastrous state… Many military commanders were sent to deal with the pretender; but they all had very little success and returned back having achieved nothing, fearing defection of their own troops, amongst whom there could be felt a considerably bigger sympathy towards the newly appeared prince, than the allegiance with emperor Isaak’ [141], p.71-72.

In the end, according to Choniates, emperor Isaak sent his brother –also called Alexius – against the ‘pretender’, but he could not do anything either. Then Pseudo-Alexius ‘disappears’ in some kind of mysterious way. Allegedly, when he fell asleep a certain priest decapitated him [141], p.73. In a short while Alexius Angelos – the brother of Isaak – deposes Isaak from the throne, becomes the king, gives up the name ‘Angelos’ and takes the name ‘Comnenus’. For absolutely inexplicable reasons! The event is so strange that Choniates, feeling it, tries to give here some kind of explanations. Albeit rather confused. [141], p.118.

There emerges a clear impression that Alexius Comnenus was not murdered and in fact came to power for the second time. Otherwise before us there is a repetition of Alexius Comnenus’ story shifted by just a few years. Either way on the pages of ‘Historia’ by Choniates there are present the two kings with two completely identical names – Alexius Comnenus. Therefor it has to be expected that the events under one Alexius could be attributed to the other and vice versa. While some of them, not being identified as the duplicates, could have been mentioned twice. This is exactly what we see.

41.2. RECURRENCE OF THE STORY OF CHRIST-ANDRONICUS UNDER THE ‘SECOND’ ALEXIUS COMNENUS.

We shall remind you that according to Choniates Andronicus Comnenus rebels against the ‘first’ Alexius Comnenus and seizes power from him. A certain CHRIS rebels against the ‘second’ Alexius Comnenus. He is already mentioned under Isaak Angelos but the main events connected with Chris unfold under the ‘second’ Alexius Comnenus. Chris’ revolt started under Isaak Angelos. It is said that a certain Chris ‘conceived to obtain an independent rule and therefore was captured and taken into custody. He was then set free … but he dashed the emperor’s hopes … and abusing his rank, became a relentless enemy of the neighbouring Romans’ [141], p. 151-152. They tried to capture him for a long time to no avail [141], p.157. But Isaak Angel did not succeed in it.

Having ceased power, Alexius Angelos, who ‘renamed himself’ as Alexius Comnenus, also fights against Chris [141], p.171. However Chris hid himself in some kind fortified place. ‘Having such a fortification at his disposal Chris did not fear the emperor’s campaign whatsoever ’ [141], p.172. There is a lot said about a lengthy and unsuccessful struggle with Chris – over the seven pages. The emperor could not capture Chris and marries one of his relatives off to him. Then Chris disappears from the pages of Choniates’ ‘Historia’ altogether.

On the whole Chris’ story remarkably resembles the story of Andronicus-Christ before his enthronement. Like Chris, Andronicus was jailed, but escaped the prison. Then he spent a long time in exile and they constantly tried to capture him as a claimant to the royal throne. The same is said about Chris. We would like to note now that the name ‘Chris’ itself is virtually identical to the name ‘Christ’. Thus we can see the duplication of Andronicus’ story, but under the name of ‘Chris’ – Christ. However, Choniates did not see this story through to the end. Nevertheless, there is a distinct trace of Christ’s story.

Over some time after Chris disappears from the pages of ‘Historia’ by Choniates there flares up a dispute about the Resurrection and the body of Christ. Where it was stressed that this dispute concerned a new subject which had never been discussed before. ‘A NEW TEACHING about Holy Communion comes to general attention. This teaching caused division between the Christians into two opposing parties; so that in the streets as well everyone was giving their own interpretation of the subject matter… The question was in the following: ‘Is the Holy Body of Christ which we take a communion of as incorruptible as it became after the passion and the Resurrection, or is it perishable as it was before the passion [141], p.185-186.

Moreover the dispute unravelled not only around Christ’s Resurrection, but also about the way those resurrected should behave. A heated discussion takes over several pages of Choniates’ writing. Here is just one of the examples: ‘Because, as they were saying … when resurrected we also will be beyond the tactile sensation, being visible or any definite human form, but will be hovering in the air like some immaterial shadows’. In regards to this last idea they insisted that Jesus entering the room where his disciples were, when the doors were shut, was not a miracle, but a natural and typical of anyone resurrected from the dead’ [141], p.188.

Thus the Gospel events were discussed as the very recent ones, which just took place. People had heated debates about miracles of Christ, and whether they also will be able to perform such miracles after their own resurrection, etc. In the later epochs there were no more vocal ‘evangelical debates of that kind.

It is remarkable that under the ‘second’ Alexius Comnenus, a little bit further after the story about Chris, - i.e. precisely where it is necessary, - there follows a colourful narrative about Herodias and John the Baptist. Under the ‘first’ Alexius this story sounds muted, though some traces of it are still present.

42. HERODIAS = EUPHROSYNE.

With the accession to the throne of Alexios Angel (aka Alexios Comnenus) his wife Euphrosyne acquires excessive degree of power. Nicetas Choniates describes indignantly and at length disgraceful actions committed by Euphrosyne. Where the particular rage of the society was caused by her following actions. ‘But the sovereign lady’s shameless escapades spread even further. She knocked off the genitals of some statues depicting men; and DECAPITATED the others STRIKING THEM WITH A SLEDGE HAMMER ON THE HEAD. For that there was no shortage of unseemly indecencies in her address in the city and bad mouthing by the crowd for such deeds’ [14d1], p.191. She was also accused of ‘CUTTING OFF THE NOSE OFF ‘Calydonian boar’, a brass statue in the Hippodrome… gave a violent shellacking on the back to the famous ‘Hercules’, a divine creation by Lysimachus representing a hero lying down on the spread LIONS SKIN’ [141],p.191.

This text is rather vague, but a theme of abuse or mutilation, murder of a certain famous man sounds clearly in it. Which incited fury and hatred of the entire city towards her. Certainly, such a description by itself is not sufficient enough to consider it to be the trace of Herodias in the story of John the Baptist. But literally in two pages Nicetas Choniate describes an incident which unequivocally refers to John the Baptist. After this, identifying Euphrosyne with Herodias seems quite obvious.

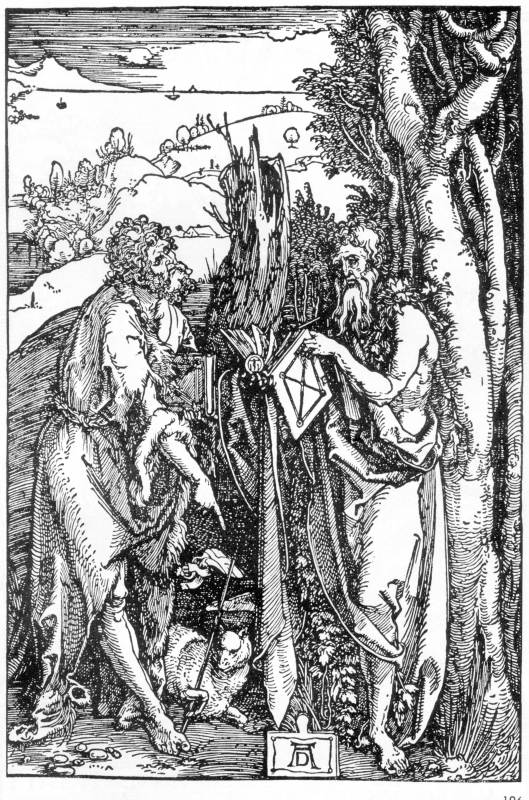

By the way, in regards to the LION’S SKIN which ‘Hercules was lying on’. Let us remember that John the Baptist was wearing animal skins: ‘John had his raiment of CAMEL’S HAIR AND A LEATHERN GIRDLE about his loins’ (Matthew 3:4). See for example fig.2.88  . Besides, as we have already noted in our book ‘Novaya Chronologia Egipta’ (‘The New Chronology of Egypt’ – Tr.), there are ‘ancient’ – Egyptian images of a man wearing LION’S SKIN, who baptising people, pouring water on them from a jug. See for example, fig.4.23

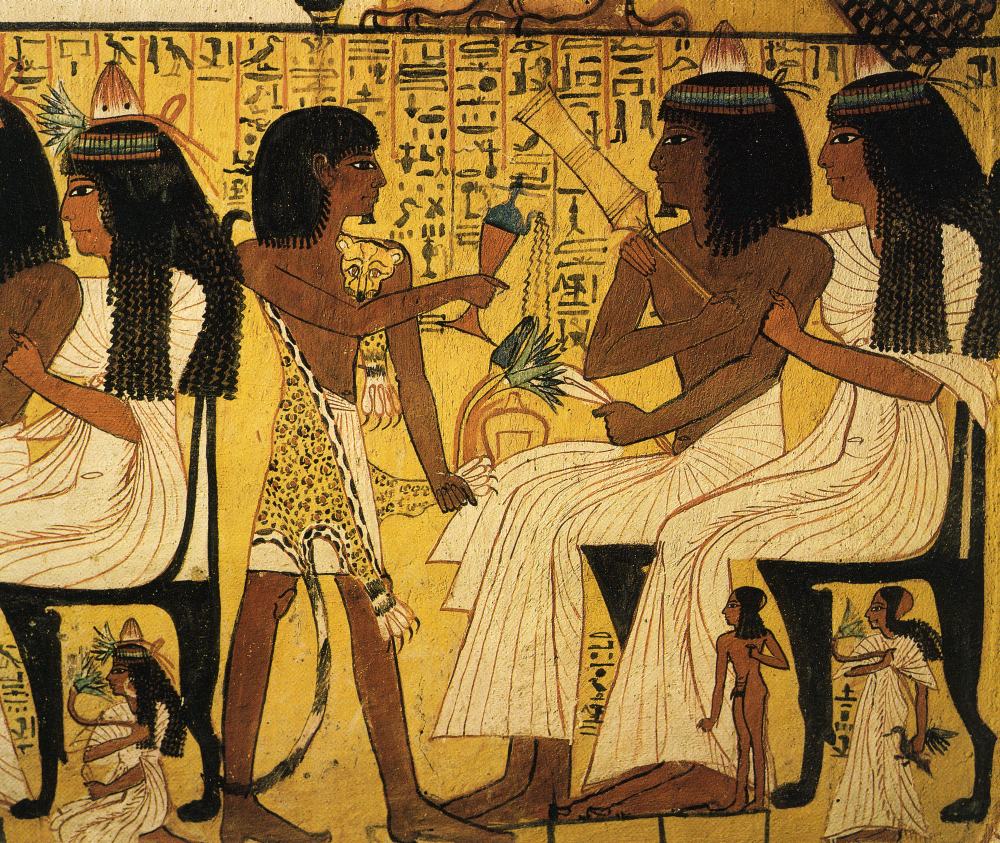

. Besides, as we have already noted in our book ‘Novaya Chronologia Egipta’ (‘The New Chronology of Egypt’ – Tr.), there are ‘ancient’ – Egyptian images of a man wearing LION’S SKIN, who baptising people, pouring water on them from a jug. See for example, fig.4.23  in the aforesaid book [MET3]. We have already noted that it is most likely a depiction of John the Baptist. Aka the Egyptian Aquarius (Water-Bearer). In the sky it corresponds with the zodiacal constellation of Aquarius. In fig.2.89

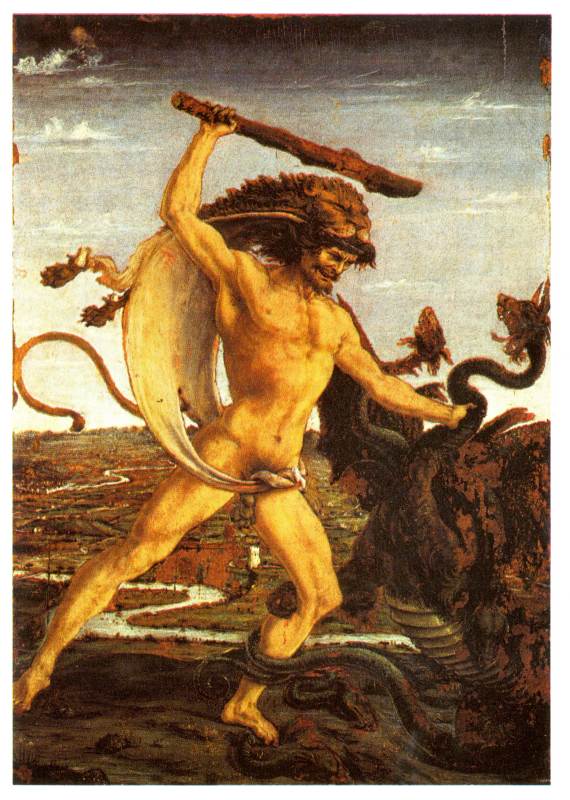

in the aforesaid book [MET3]. We have already noted that it is most likely a depiction of John the Baptist. Aka the Egyptian Aquarius (Water-Bearer). In the sky it corresponds with the zodiacal constellation of Aquarius. In fig.2.89  is presented a painting by Antonio Pollaiuolo ‘Hercules and the Hydra’. A LION’S SKIN is slipped on Hercules.

is presented a painting by Antonio Pollaiuolo ‘Hercules and the Hydra’. A LION’S SKIN is slipped on Hercules.

43. JOHN THE BAPTIST = JOHN COMNENUS.

Having given us his account of Euphrosyne – Herodias, Nicetas Choniates inserts another colourful duplicate of the story of Andronicus-Christ. This time Christ is called John Lagos. Here quite openly sounds the name LAGOS. As LOGOS or LAGOS, i.e. ‘Word’ (‘Slovo’ in Slavic) is one of the names of Christ (John 1:1). We will talk about this duplicate of Christ in the later paragraph, but now we shall proceed on to John the Baptist, whom Choniates begins to speak of IMMEDIATELY AFTER Lagos – Christ. We shall note that the resulting sequence of events is exactly the same as in the book ‘Strasti Christovy’ (‘Passion of Christ’). We have already pointed out earlier that in this book the execution of John the Baptist is placed AFTER the capture and Passion of Christ.

We quote Choniates: ‘Hardly had this calamity passed (i.e. ’Logos revolt’ – Author), when a certain man by the name of JOHN from the Komnenoi clan rebelled against the emperor… Unexpectedly storming into the Grand Cathedral John laid one of the wreaths upon his head, which were hanging around the altar and looking this way presented himself to the people… Accompanied by the people who had gathered largely by hearsay about the happening event, he entered unobstructed the Great castle, sat on the gilded throne and embarked on appointing various personages to the highest posts; meanwhile the mob together with some of the rebels … proclaimed him the Roman Emperor. As night fell John did not see properly to either installing the guards in the palace, or restoring its smashed gates; but … was PUFFING AND PANTING ALIKE TO A DOLPHIN, DEVOURING ENTIRE JUGFULS OF WATER… At this time the king sent his attendants and the members of his family who were with him ordering them under the shelter of night TO ATTACK JOHN … The king’s men … TRACKED HIM DOWN, MURDERED HIM … AND BROUGHT HIS DECAPITATED HEAD TO THE KING. The head of the rebel was IN A NOOSE lifted above in the middle of the trading square for everyone to see’ [141], p.198-200.

Here we see literally all the core components of the Gospel story about the death of John the Baptist. We shall give you a brief reminder of the Gospel story. John the Baptist was the famous prophet, greatly respected by the people. Between him and king Herod there arose a conflict as the Baptist argued against Herod’s marriage to Herodias. Herod puts John the Baptist in prison. Then at the instigation of his relatives – his wife Herodias and her daughter Salome – he sends off to kill John the Baptist. John is executed, he is decapitated and his head is brought to Herodias on a platter (Matthew 14:3-12). Incidentally it is stressed that Herod wants to put John to death, but he fears the people, who regard him as a prophet (Matthew 14:5).

Nicetas Choniates fundamentally says the same thing, but in slightly different way and from a different perspective. Judge for yourself.

- JOHN THE BAPTIST AND CHRIST – ARE RELATIVES. The Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 1:36) directly refers to it. We see the same in Nicetas Choniates’. I.e., John Comnenus (i.e. John the Baptist) is a relative of Andronicus Comnenus (i.e.Christ). They both have the same family name of Comnenus (the Komnenoi).

- BAPTISM BY WATER. John the Baptist preaches baptism by water. In many images he is shown next to the water, baptising in the river, etc. And according to Nicetas Choniates John Comnenus has an egregious need for water. He allegedly was ‘devouring water’ in great amount and still could not quench his thirst. Here Choniates’ text sounds very strange if taken literally. It would seem that a person’s being thirsty and his craving to drink enough water is not of such utmost importance to mention historically. An impression arises that here is something much more significant. If John Comnenus is John the Baptist, then it immediately become clear what they were referring to. The later editor ‘Nicetas Choniates’ distorted the original text of the old source. It could have been done purposefully. But a clear trace of the distortion remained.

- JOHN’S ARGUMENT WITH HEROD. John the Baptist opposes King Herod, and his duplicate John Comnenus opposes emperor Alexios Comnenus. The Gospels tell us of the conflict over Herodias., i.e. the queen. Nicetas Choniates talks of the conflict over the royal power.

- Nevertheless in the end Herod achieves his goal. John the Baptist is put to death and decapitated. Nicetas Choniates tells us literally the same, but in other words. Emperor Alexios Angelos-Comnenus wants to kill John Comnenus, but fears the people. That is why he orders to kill him at night, when the people are already asleep [141], p.199. THE PERSONAL PARTICIPATION OF THE EMPEROR’S RELATIVES in this matter is being stressed. I.e. the emperor mentions the order of the murder not only to the common servants and soldiers, BUT ALSO HIS RELATIVES [141], p.199. From Choniates accounts it is not very clear what the relatives have to do with it. Why was it necessary to send them in particular to fulfil this dangerous task? In such cases they send a special ops unit, but not the relatives. Most likely here too ‘Nicetas Choniates’ distorted the original text of the old source. He kept the direct participation of the relatives in the murder of John the Baptist, but changed the description of their exact actions. Instead of mentioning the king’s wife’s demand to execute John the Baptist, Choniates stated that allegedly the emperor’s relatives together with the soldiers arrested and murdered John Comnenus.

- THE HEAD OF JOHN THE BAPTIST IS PLACED ON A PLATTER. The Gospels speak directly about it and it is depicted in various old paintings and icons. Most likely John’s head on the platter astonished the contemporaries. Nicetas Choniates reports something very similar to us. The head of John Comnenus was paraded in the market square by ‘lifting it in a noose’, see above. Let us consider for a moment what it means – to raise a decapitated head in a noose? The head was separated from the body and so it would not hold in a noose. Most likely it was meant, that the head was placed in a chalice or a platter and lifted aloft to show the people. They could have lifted it, by the way, using a rope. In regards to the word NOOSE, which was used here, it is possible that it had appeared as a result of an error by a later editor. Either deliberate or unintentionally. As the words PLATTER (BLIUDO in Russian – Tr.) and NOOSE (PETLIA in Russian – Tr.) have the same stem of the consonants when changed places and when the sound B transfers into P (B à P) and the sound D transfers into T (D à T), i.e. blyudo = BLD à PTL = petlia.

- JOHN THE BAPTIST IS A PROPHET. According to Nicetas Choniates ‘John Comnenus having stormed into the Grand Cathedral, laid one of the wreaths upon his head, which were hanging around the altar and in this way presented himself to the people…’ [141], p.198. At that the crowds of people greeted him adoringly, see above.

HEROD SENDS OFF TO PUT JOHN TO DEATH ON THE INSISTENCE OF HIS RELATIVES – HIS STEP DAUGHTER AND HIS WIFE. It is stressed that it is not an easy matter for Herod as he fears the people: ’And when he would have put him to death, he FEARED THE MULTITUDE, because they counted him as a prophet’ (Matthew (or John) 14:5)

Thus the account of Nicetas Choniates about John Comnenus is none other, but an undisguised duplicate of the Gospel story about John the Baptist.

44. JOHN LAGOS AS ANOTHER REPETITION OF THE STORY OF ANDRONICUS–CHRIST

IN THE ACCOUNTS OF NICETAS CHONIATES.

Let us get back to John Lagos, the story of whom was placed by Nicetas Choniates immediately before John Comnenus (aka John the Baptist). This is what we are told. ‘After some time passed another disaster has come about, which also ended in BLOODSHED. A certain John by the name of LAGOS having received from the king a Praetorian PRISON under his command took it into his head to extract money … from there… Many have already REPORTED TO THE KING REGARDING THE CRIMINAL ACTIONS OF THIS LAGOS, but he, after promising to amend the evil deeds, continuously postponed his decision, as if something implacable prevented him. That is why Lagos was by no means afraid and continued even completely openly perform his villainous deeds as before… Once he arrested a craftsman, gave him a good beating and condemned him to shave his head. THIS CAUSED A REVOLT... especially amongst the fellow-craftsmen of the wronged man. THE ENTIRE CITY DESCENDED INTO CONFUSION and a considerable crowd of craftsmen plunged forth into praetorian with the intention TO SEIZE LAGOS, but he fled faster than a hare and escaped the city. At the same time the new crowds of people rushed to the Great Cathedral with the aim of proclaiming a new emperor … The emperor, who was not in town at that time and who was in CHRYSOPOLIS (i.e. in the City of CHRIST – Author), sent an Imperial Guard unit to take over praetorian. But as soon as Constantine Tornikios, the governor of the capital appeared with this unit, the mob … dispersed the entire unit of the Imperial guards, then smashed open the gates of praetoria, freed all the prisoners, looted the Christian temple set up there, and razed to the ground the Saracen chapel. Having done all of this without any sense or reason, the rebels approached the so called copper prison and dealt with it in similar fashion. However when one of the emperor’s sons in law … brought with him a royal troops the riots began to cool off… By the evening the rebels retired to their homes and the next day there was neither discontent, nor any attempts at renewed fighting’ [141], p.197-198.

Here we see the repetition of the story of Andronicus-Christ, to be more precise, at the very end of his reign. We shall remind you that the mutiny against Andronicus was instigated by the nobles who were outraged that Andronicus treated them too harshly and did not want to temper justice towards the rich and noble. Including his relatives. The offended nobles mutinied, assembling in the Great Cathedral and proclaiming a new emperor there. At that time Andronicus is outside the capital in his country palace. He sends his supporters to tame the uprising, but they fail to do so. The revolt is accompanied with the destruction of the prisons and the palaces. ‘Next they broke the keys and the bolts of the public prisons and set the prisoners free; these were not all criminals, but many were members of the illustrious families… The mob plundered not just the treasures which were kept in CHRISIOPLISII(it is possibly the treasury – Author)… but from the armoury a large amount of weapons were also stolen. The looting spread to the temples which were situated in the royal palace’ [139], p.434-437. Then the new emperor Isaac Angelos enters the palace and the mob’s rage abates.

Literally the same thing is described by Choniates once again as ‘Lagos’ revolt’. Lagos is the prison governor and ‘oppresses the good tradesmen’. The outraged ‘tradesmen’, offended by such treatment raise a rebellion and rush towards the Great Church to proclaim a new emperor. The name of the new emperor is not given. It is clear why. Choniates inserted this story in the wrong place, in the middle of the reign of Alexios Angelos-Comnenus. So the ‘new emperor’ would have been out of place here. So his name had to be ‘forgotten’. Nevertheless, the trace remained.

The rebellion in Lagos, as in the deposition of Andronicus, is accompanied by the destruction of the prisons, setting the prisoners free, and looting of the churches. As in the story of Andronicus, the emperor is at that moment away from the city and a legion he sent to the capital could not stop the rebels. Here Choniates’ story about the Lagos rebellion basically fades away: ‘Next day there was neither any discontent, nor any attempts for repeated fight’ [141], p.198. Here Choniates ends the ‘insert’, forgets about it and smoothly proceeds to continue the story about Alexios Angelos-Comnenus.

It is possible that the events associated with Andronicus-Christ were so often discussed in the primary sources used by Nicetas Choniates, that he several times repeats this description in his ‘Historia’. Once – detailed and more or less fully. And on the other occasions - rather vaguely and fragmentarily.

45. A FURTHER VAGUE REFERENCE TO A REVOLT AGAINST ANDRONICUS-CHRIST AS ‘THE EXPULSION

FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN’.

Among the numerous repetitions of the story about Andronicus, the majority of which are vague and fragmentary, the following one attracts attention. The interesting thing about it is that it presents the revolt against Andronicus-Christ as the expulsion of the forefathers from Paradise. Presumably in some old primary source used by Choniates this idea resonated clearly. Andronicus’ reign was called the time of Paradise, and the revolt against him – the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Naturally Choniates was already educated in the ‘correct history’ and obediently tries to reconcile the unpolished true testimonies of the old sources with the scaligerian chronology he had been indoctrinated with. This is the result he comes up with.

Just before the story about Logos revolt Nicetas Choniates inserts the following storyline. ’There was a certain money-changer, Kalomodios by name. He was laden with much money, and, greedy of gain, he often set forth on long and arduous journeys for the purposes of trade...A skinflint who … placed everything second to making money, he often provided the gold-hunting EMPEROR’S PEOPLE with the occasion to view him as the richest of men and as Alkinoos’ orchard, where, in but a moment, not pear bore pear and fig yielded fig but gold brought forth gold and silver produced silver. He was undisguisedly the TREE OF KNOWLEDGE planted in the City’s agora and lanes AS THOUGH IN THE GARDEN OF EDEN. Just as long ago THE FRUIT’S FULL BLOOM ENSLAVED OUR FIRST ANCESTORS, so did the gold’s gleam tempt THE EMPEROR’S FINANCIAL OFFICERS to gather it in. But as soon as THEY LAID HANDS ON KALOMODIOS, THEY STIRRED UP THE CITY TO SEDITION as though they had suffered a worse calamity than our first parents. When the vulgar masses learned of Kalomodios’ arrest that evening and discovered the reasons, they gathered in groups at dawn and entered the temple of God, where they beheld the chief high priest (this was John Kamateros). They surrounded him and almost threatened to tear him apart and throw out of the window head down if he immediately didn’t send a message to the Emperor and didn’t return Kalomodios to them like a kidnapped and PERISHED LAMB. Scarcely having appeased the masses’ movement … PATRIARCH IN FACT RETURNED KALOMODIOS TO THEM like a REDEEMED LAMB’ [141], p.195-196.

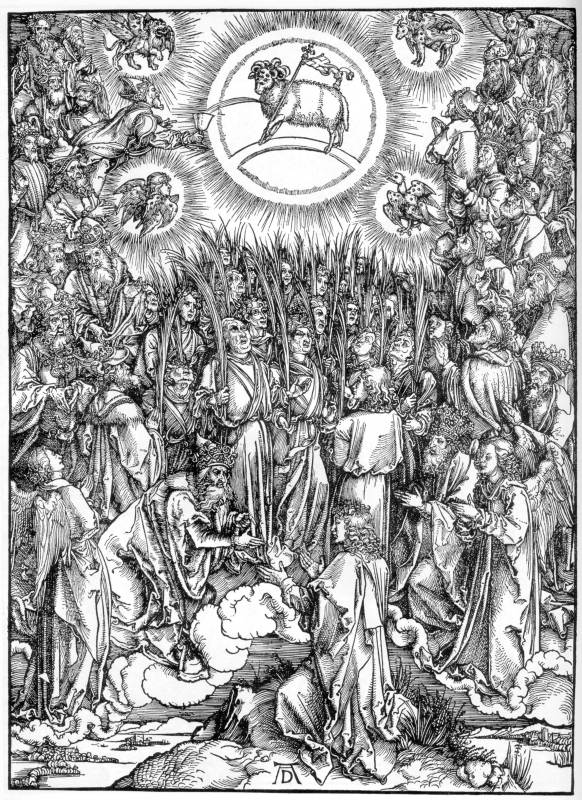

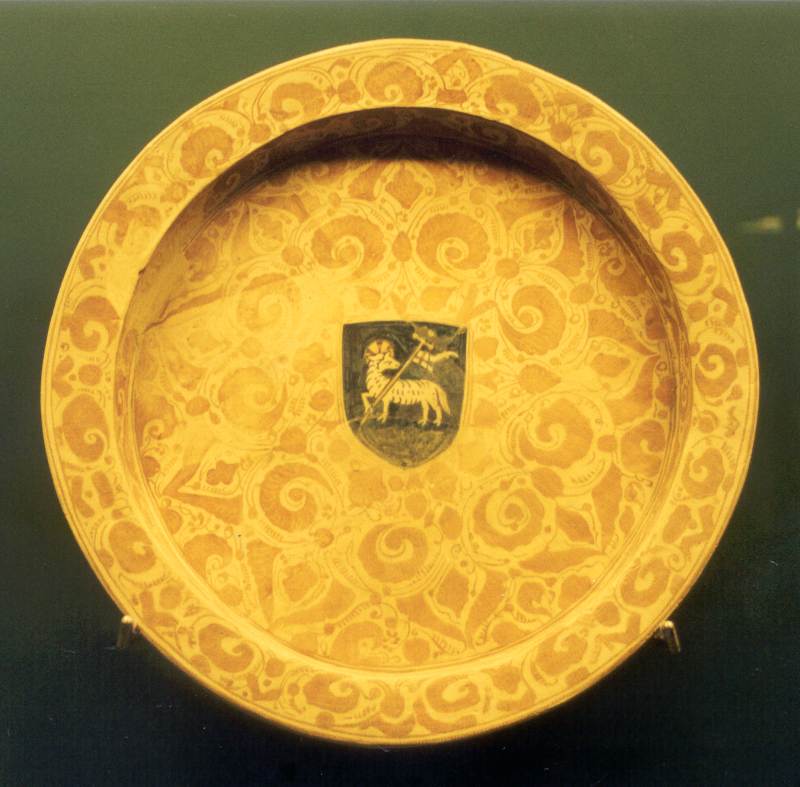

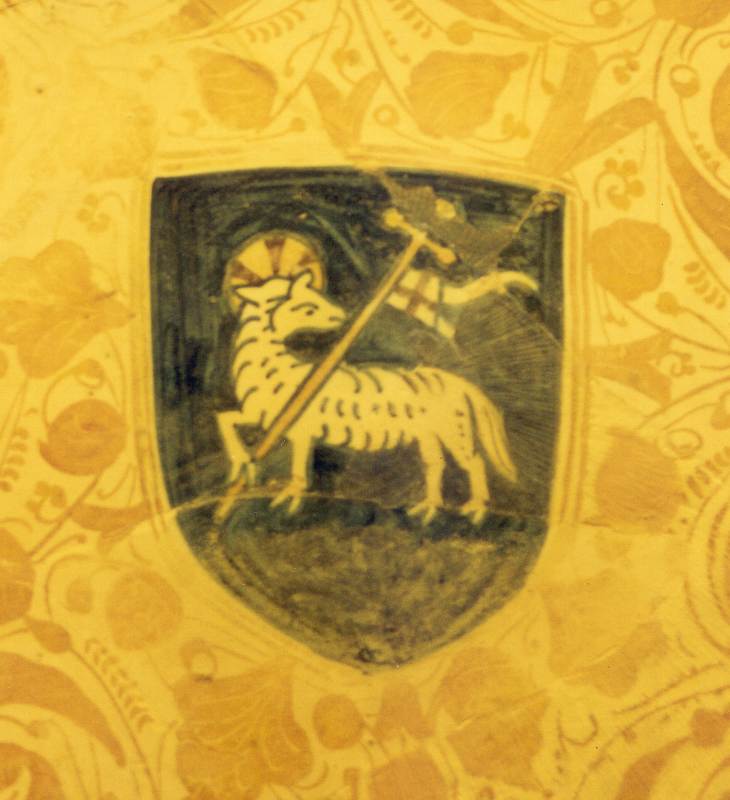

The text is rather opaque, but the true meaning of the primary source shines trough it enabling its restoration in the following way. It is likely that the story of Andronicus-Christ was told as the ‘creation of Paradise’ on earth, followed by committing sin and as a consequence banishment from Paradise. Where the sin is closely connected with a certain tree. Most likely with a cross = a tree of Christ which he was crucified on. Eventually the heavenly life ended and just a memory of it as of a Golden Age was left behind, see above. Even the beginning of the story about Kalomodios resembles the beginning of Andronicus’ reign. He travels a lot, he is hounded by the ‘emperor’s people’. But having overcome all the severities he finally ‘fully blooms like the garden of Eden’ in the squares of Czar Grad. I.e. most likely he is enthroned as an emperor. Both the description of the riot which broke out when Kalomodios was arrested and the public commotion in the Great church correspond well with the story of Andronicus. Nicetas Choniates’ comparison of Kalomodios with a LAMB, i.e. HOLY LAMB sounds dramatic. But the Holy Lamb is one of the most widely known symbols of Christ, see for example fig.2.90  , fig.2.91

, fig.2.91  , fig.2.92

, fig.2.92  , fig.2.93

, fig.2.93  .

.

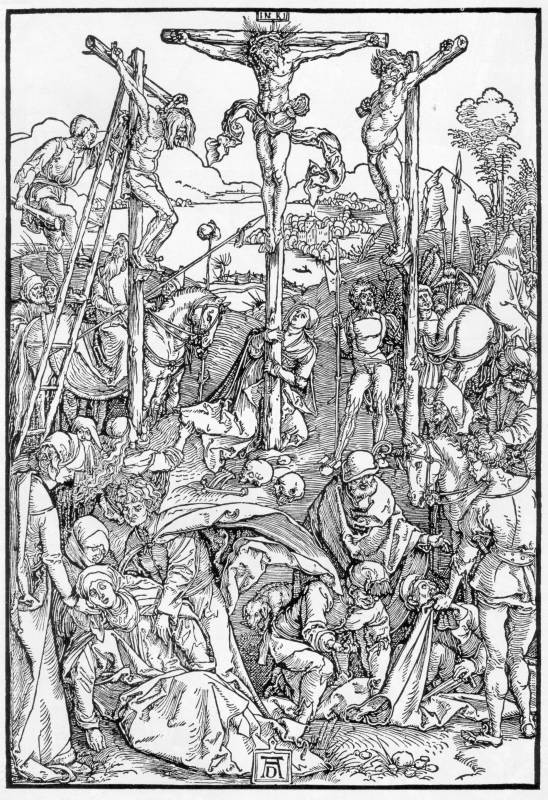

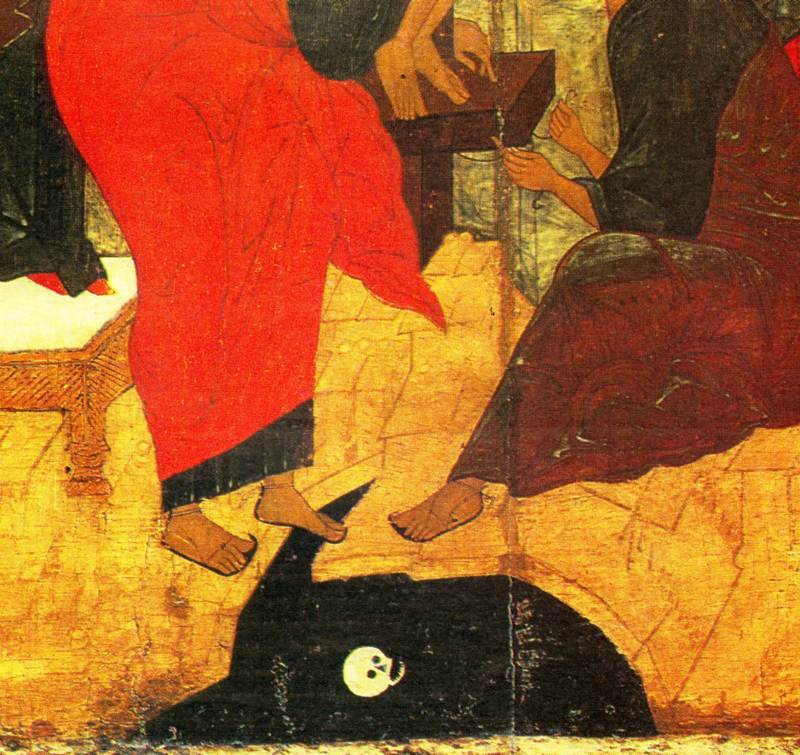

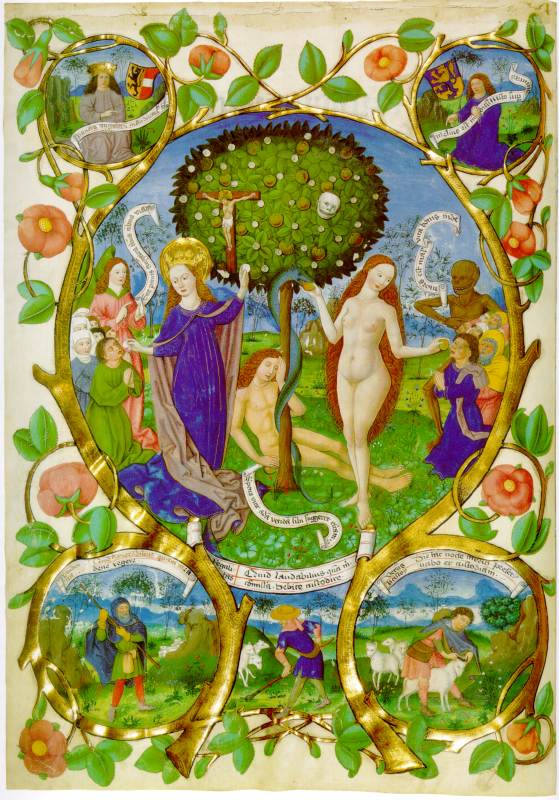

Now emerges a new meaning of the well known Christian image, where Adam’s skull is depicted under Christ’s crucifixion. See for example fig.2.60  , fig.2.61

, fig.2.61  , fig.2.62

, fig.2.62  and fig.2.94

and fig.2.94  . If Banishment from Paradise was the revolt against Andronicus-Christ, than there emerges a close connection between Adam, the Garden of Eden and Christ’s crucifixion. Moreover, in the old Christian writings, - see for example ‘Skazaniye o krestnom dreve’ (A legend of the True Cross or Cross Tree), which today are declared as apocryphal, it is stated that the cross which Christ was crucified on was made of the wood from the Garden of Eden, i.e. from a tree which once grew in the garden of Eden [109], [9], p.121. The old images supporting this theory, see for example fig.2.95

. If Banishment from Paradise was the revolt against Andronicus-Christ, than there emerges a close connection between Adam, the Garden of Eden and Christ’s crucifixion. Moreover, in the old Christian writings, - see for example ‘Skazaniye o krestnom dreve’ (A legend of the True Cross or Cross Tree), which today are declared as apocryphal, it is stated that the cross which Christ was crucified on was made of the wood from the Garden of Eden, i.e. from a tree which once grew in the garden of Eden [109], [9], p.121. The old images supporting this theory, see for example fig.2.95  , survive until now. Here for example, Christ’s crucifix is placed directly on the top of the Eden tree. On the left of the tree we see the Mother of God standing next to the crucifix. In the centre there is Adam, to the right there is Eve. Besides, in the crown of the tree also on the right there is depicted Adam’s skull. The idea of identification of Christ’s cross-post with the Tree of Eden or the World Tree (the Tree of Life) was also well known in Mediaeval England. In fig.2.96

, survive until now. Here for example, Christ’s crucifix is placed directly on the top of the Eden tree. On the left of the tree we see the Mother of God standing next to the crucifix. In the centre there is Adam, to the right there is Eve. Besides, in the crown of the tree also on the right there is depicted Adam’s skull. The idea of identification of Christ’s cross-post with the Tree of Eden or the World Tree (the Tree of Life) was also well known in Mediaeval England. In fig.2.96  there is presented a depiction of the World Tree simply identified with the Christian Cross. The commentators inform us: ‘The Manx rune stone from the Isle of Man, Great Britain. 10 century. The drawings kept the echo of the mythological perceptions of the WORLD TREE (WHICH ITSELF HAS BEEN ALREADY REPLACED WITH THE IMAGE OF THE CROSS)’ [95], v.1, p.479.

there is presented a depiction of the World Tree simply identified with the Christian Cross. The commentators inform us: ‘The Manx rune stone from the Isle of Man, Great Britain. 10 century. The drawings kept the echo of the mythological perceptions of the WORLD TREE (WHICH ITSELF HAS BEEN ALREADY REPLACED WITH THE IMAGE OF THE CROSS)’ [95], v.1, p.479.

The name ADAM itself means a MAN [95], v.1, p.42. Which places it closer with the name ANDRONICUS and with the Gospel name Christ – the Son of MAN. Moreover, Christ was called the second Adam or the New Adam [95], v.1, p.42.

The very end of the story about Kalomodios is presumably an allegorical description of the resurrection of Christ. The ‘perished lamb’ (Kalomodios) was returned as the HOLY LAMB FOUND, i.e. so to speak ‘resurrected’.

The name ‘Kalomodios’ reminds of the name KOLIADA. But Koliada is a folk name of Christ [28]. Hence incidentally, KOLYADKI – the celebration of the Nativity of Christ [152].