Auxiliary illustrations

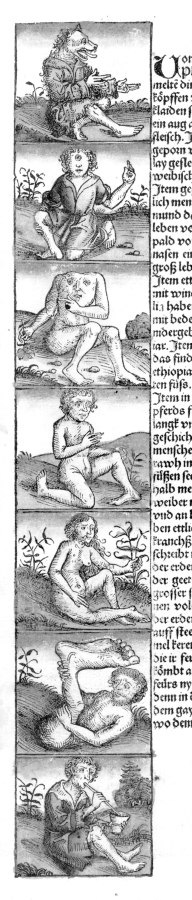

Fig. 5dp-01a. Denizens of the Horde (or Russia) as seen by the West Europeans. Engraving from the “Global Chronicle” of Hartmann Schedel (allegedly dating from 1493). All such artwork is based on real characteristics pertaining to the nations inhabiting Russia in the XIV-XVI century, which were misunderstood and greatly distorted by the Western European chroniclers. Taken from [1396:1], page XII. See more on the subject in CHRON5, Chapter 8:6.7.

Fig. 5dp-01b. Denizens of the Horde (or Russia) as seen by the West Europeans. Engraving from the “Global Chronicle” of Hartmann Schedel (allegedly dating from 1493). All such artwork is based on real characteristics pertaining to the nations inhabiting Russia in the XIV-XVI century, which were misunderstood and greatly distorted by the Western European chroniclers. Taken from [1396:1], page XII. See more on the subject in CHRON5, Chapter 8:6.7.

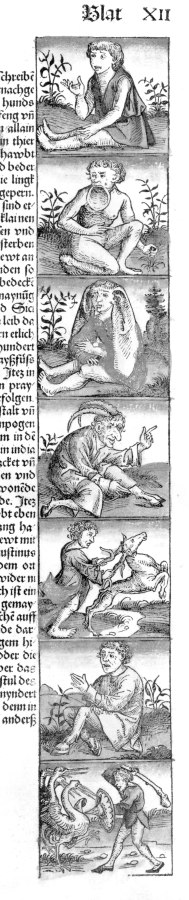

Fig. 5dp-01c. Denizens of the Horde (or Russia) as seen by the West Europeans. Engraving from the “Global Chronicle” of Hartmann Schedel (allegedly dating from 1493). All such artwork is based on real characteristics pertaining to the nations inhabiting Russia in the XIV-XVI century, which were misunderstood and greatly distorted by the Western European chroniclers. Taken from [1396:1], page XII, reverse. See more on the subject in CHRON5, Chapter 8:6.7.

Fig. 5dp-02. Silver thaler (known as “yefimok” in Russia) with a Russian crest. More details concerning this type of coinage as well as the tribute paid to Russia and the Ottomans = Atamans by the Western Europe in the epoch of the XIV-XVI century can be found in CHRON5, Chapter 12:4.1. Taken from [80:1], Volume 1, page 405.

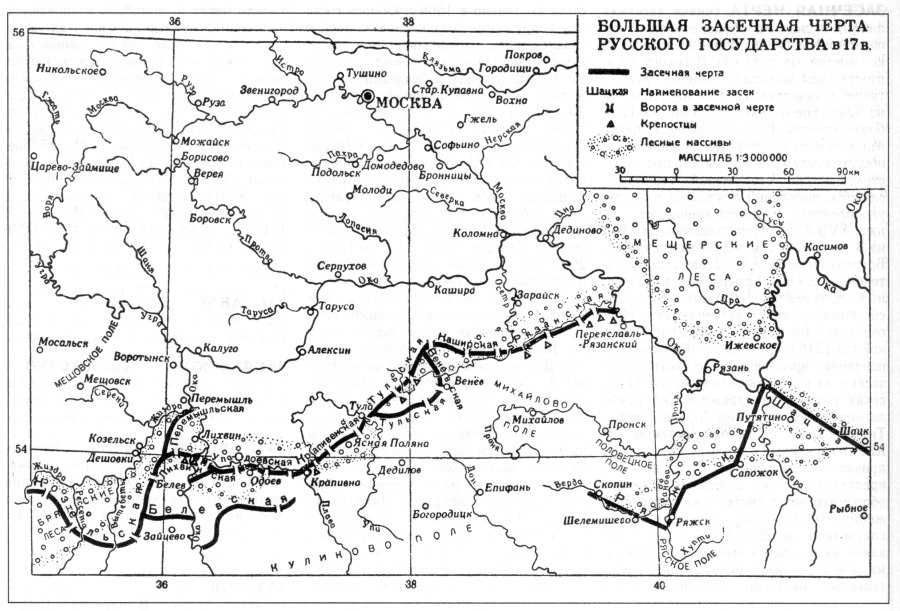

Fig. 5dp-03. The Greater Fortification Line of the Muscovite Kingdom in the XVII century. Such lines of fortification constructions protected the borders of Russia from the south and the southeast in the XVI-XVII century. It is assumed that all these fortifications were built as a defensive measure “against the raids of the Tartars, and also used as military bases during campaigns against the Khans of Kazan and the Crimea. The Greater Fortification Line of the Muscovite Kingdom is the most famous of them all – it was part of the general national defence system and consisted of military outposts, Cossack settlements and fortified citadels (40 of the latter are known to have existed in the early XVII century) . . . Fortification lines included log barricades in the forests and earth ramparts in open areas, as well as forts or small fortified settlements” ([80:1], Volume 1, page 427). According to our reconstruction, all these fortifications were built by the Romanovs to define the borders between the relatively small Muscovite Principality, which was under their control, and the lands that still identified with the Horde, such as the Astrakhan Horde and Great Tartary, which had spanned the enormous territories beyond the Volga, the entire Siberia and a large part of America. See CHRON7, Chapter 9 for more details. Taken from [80:1], Volume 1, page 428. The Great Wall of China must have been constructed around the same time and for a similar purpose, namely, the definition of a state border.

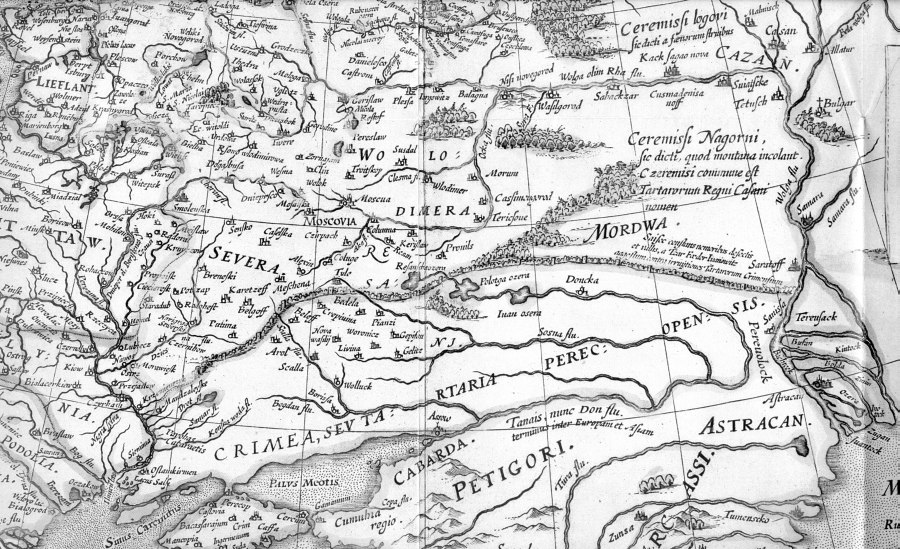

Fig. 5dp-04. Greater Fortification Line of the Muscovite Kingdom in the XVII century on a map of 1613, published by G. Gerrits in Amsterdam. Taken from [626] – [629]. Apparently, a similar role was played by the Great Wall of China, which separated the Dapple Horde (a fragment of the former Great = “Mongolian” Empire) from the Romanovs, who had usurped the throne in the imperial capital. According to our reconstruction, the Great Wall of China was also built in the XVII century, likewise the Greater Fortification Line in the south of the Muscovite Kingdom. See more on the Great Wall of China in CHRON5, Chapter 6:5.1. Therefore, it is most likely that the Greater Fortification Line and the Great Wall of China were built for similar purposes and in the same epoch.

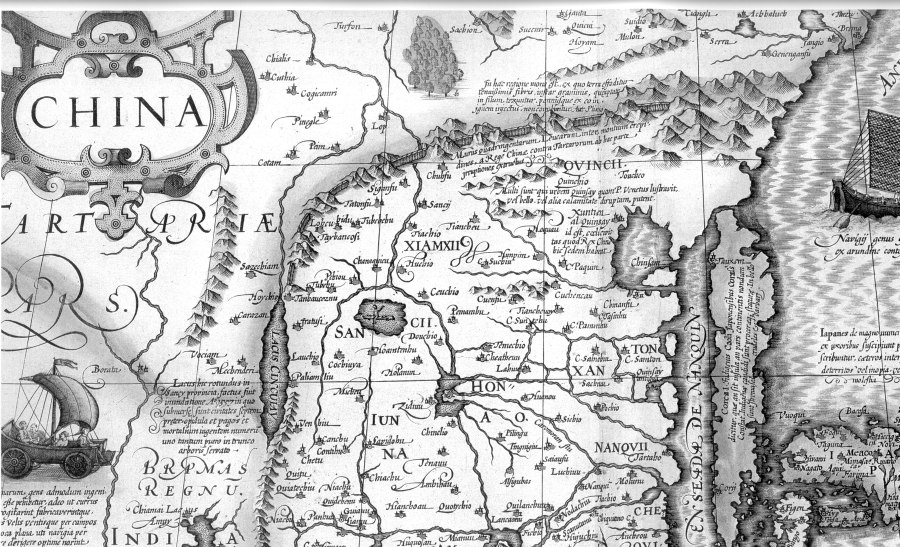

Fig. 5dp-05. Fragment of a map of China allegedly dating from 1619 from the Atlas of Mercator and Hondius. We see the Great Wall of China, which goes right along the border of China as it was in the early XVII century (or even later). This is all the more obvious on the coloured map, where the borders are drawn as yellow and red lines. We see a yellow line and a red line, both of which follow the Great Wall of China. Such disposition of the Great Wall gets a perfect explanation in our reconstruction – the long wall was used to define the state borders in the XVII century, the epoch when the Great = “Mongolian” Empire broke apart. The Dapple Horde, which later became China, proclaimed independence from other parts of the Empire. Also, the Great Wall had never served the purpose of an actual military fortification. See CHRON5, Chapter 6:5.1.

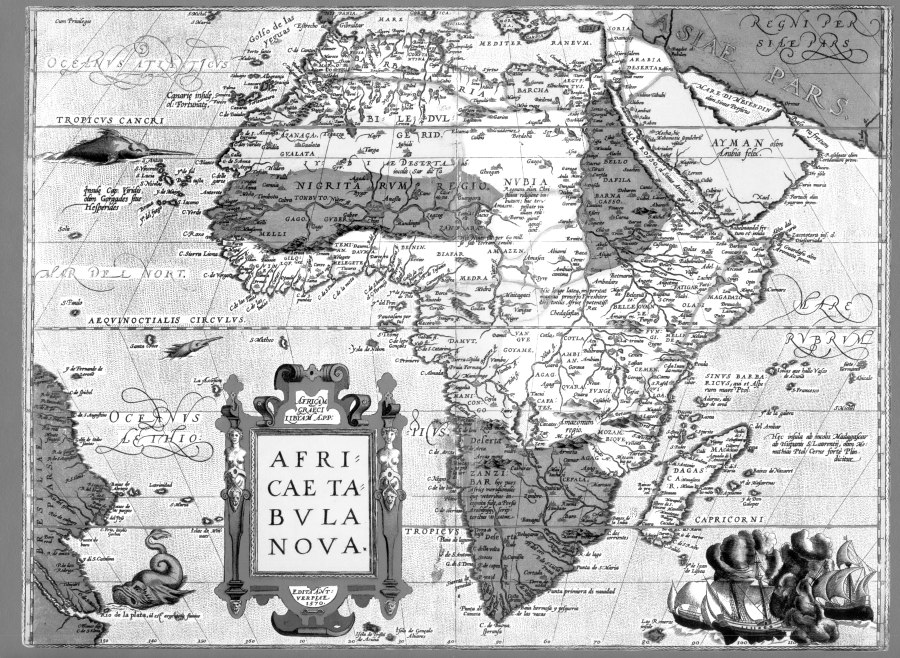

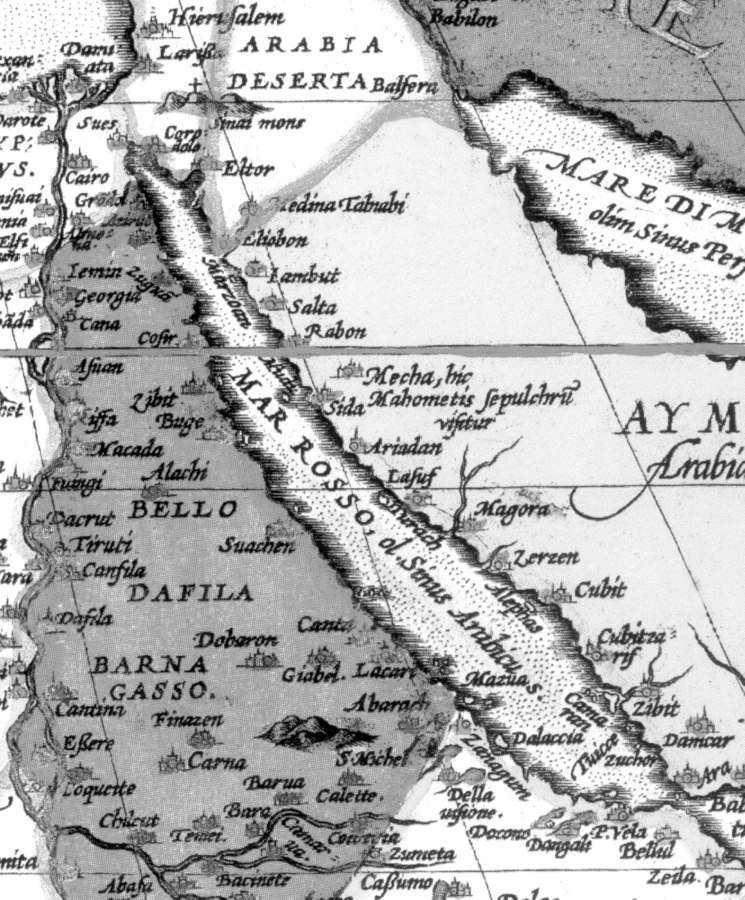

Fig. 5dp-06. Map of Africa from the atlas of Abraham Ortelius dating from the alleged years 1570-1612 A. D. It is remarkable that sea that separates Africa from Arabia, which we know as the Red Sea, is called “Mar Rosso” – could it stand for “Russian Sea”? There is also a city of Belugaras in the far South of Africa – a reference to the Bulgarians, perhaps? Abraham Ortelius: “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum”. Taken from [1261:1].

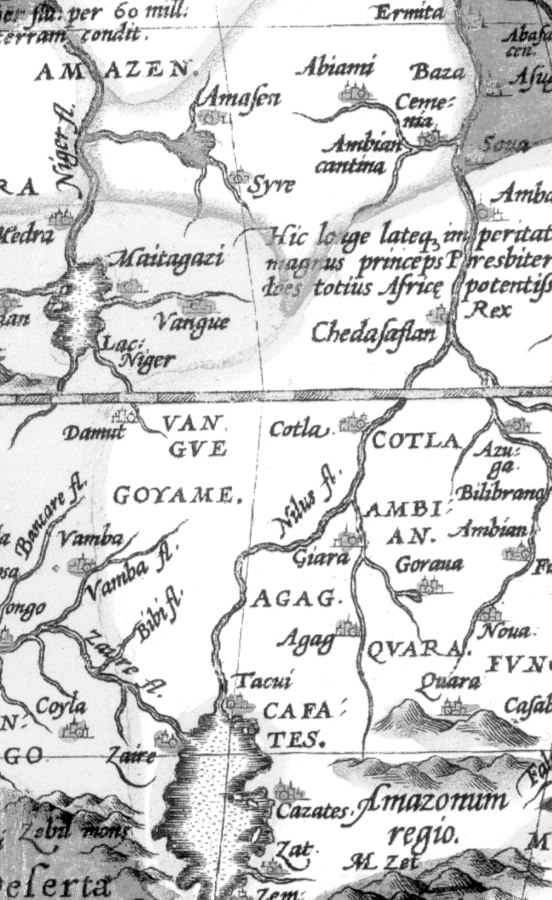

Fig. 5dp-06b. Fragment of an ancient map of Africa compiled by Ortelius in the alleged years 1570-1612. We see a region called “Amasonum Regio” in South Africa (Amazon Kingdom?). There is also the land of Amazen (Amazons?) in Central Africa, north of the Equator. To the north of “Amasonum Regio” we see the land of Agag and the city by the same name, which must be the well familiar name Gog, common in the Horde. Also mark the region of Gaoga in Nubia, qv in the photograph of the whole map. Abraham Ortelius: “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum”. Taken from [1261:1]. See more about the Amazons, or the Cossack women, in CHRON4, Chapter 4:6.

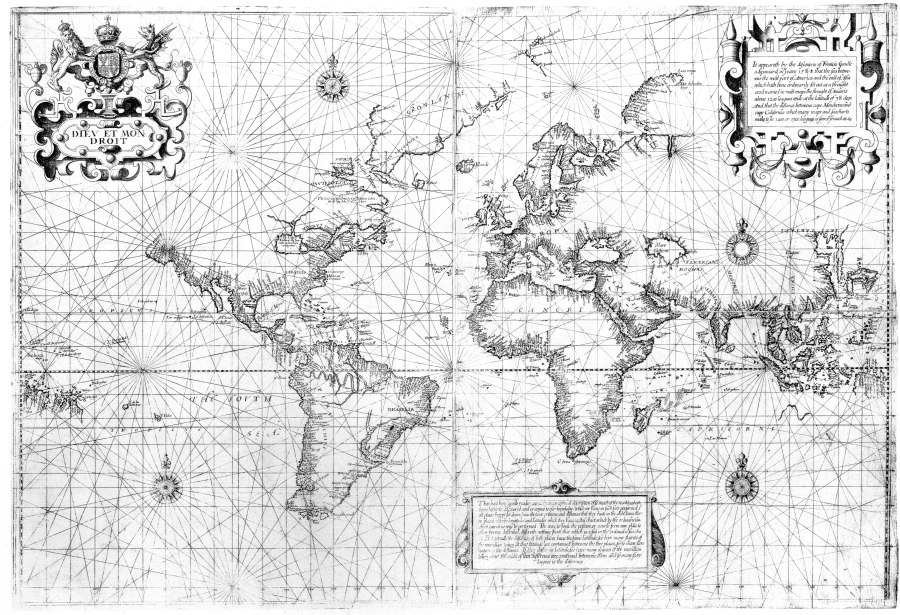

Fig. 5dp-07. We see a “Mar Rosso” (Russian Sea?) on an old world map allegedly dating from 1598 (the Wright-Molyneaux World Map). Taken from [1459], Plate XLV, No. 166. We reproduce the entire map as well as close-ins of two fragments thereof depicting Mar Rosso (the modern Red Sea).

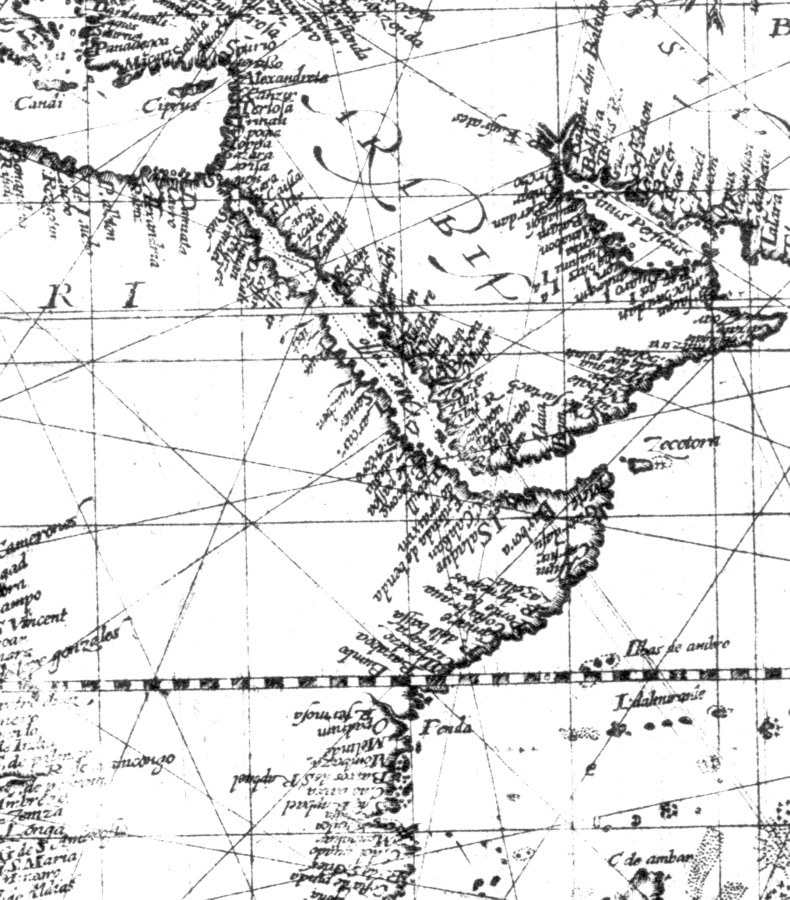

Fig. 5dp-07a. Fragment of a map of 1598 that depicts Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. The Red Sea is referred to as “Mar Rosso” (Russian Sea?). Taken from [1459], Plate XLV, No. 166. This name is also encountered on the old map of Abraham Ortelius. See Abraham Ortelius: “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum” ([1261:1]).

Fig. 5dp-07b. The Red Sea is referred to as “Mar Rosso” on the map of 1598. Taken from [1459], Plate XLV, No. 166.

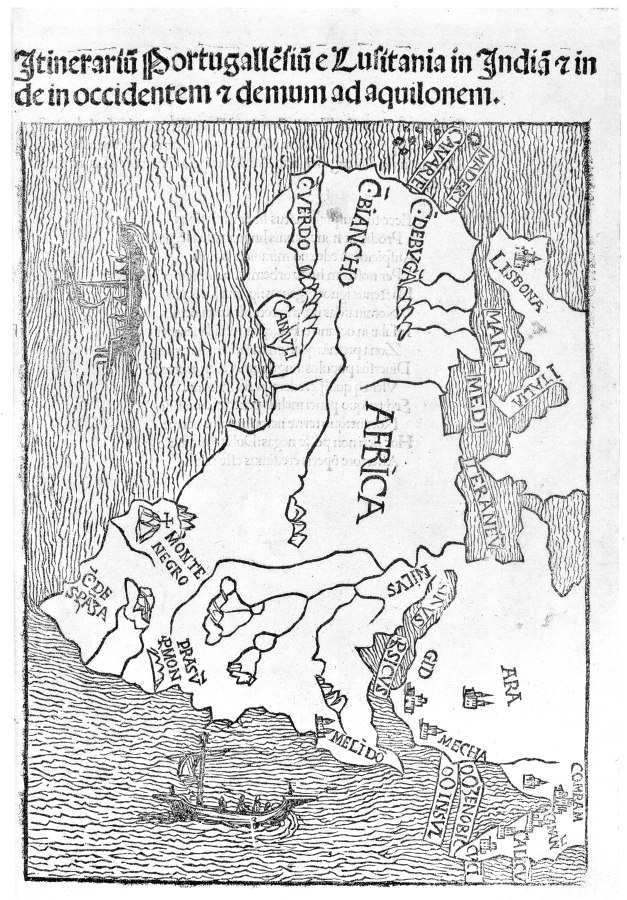

Fig. 5dp-08. Fragment of an ancient map of Africa and Arabia allegedly dating from 1508: Montalboddo, “Iternarium Portugallensium . . .”, Milan, 1508. The sea between Africa and Arabia, which we know as the Red Sea today, is called “SINVS RSICVS”, or “Rusicus Bay” – “Russian Bay”, perhaps? Taken from [1459], Plate XXIV, No. 69. Later on, in the epoch of the XVI-XVII century, this name transformed into “Persian Gulf” and moved to the East, while the former “Russian Sea” became the Red Sea.

Fig. 5dp-08a. Fragment of an ancient map of Africa and Arabia allegedly dating from 1508 (close-in). We see the name “SINVS RSICVS” applied to the Red Sea. Taken from [1459], Plate XXIV, No. 69. We see a similar name on the map of Ortelius (“Mar Rosso”), and also on a map of 1598. See Abraham Ortelius: “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum” ([1261:1]; also [1459], Plate XLV, No. 166).

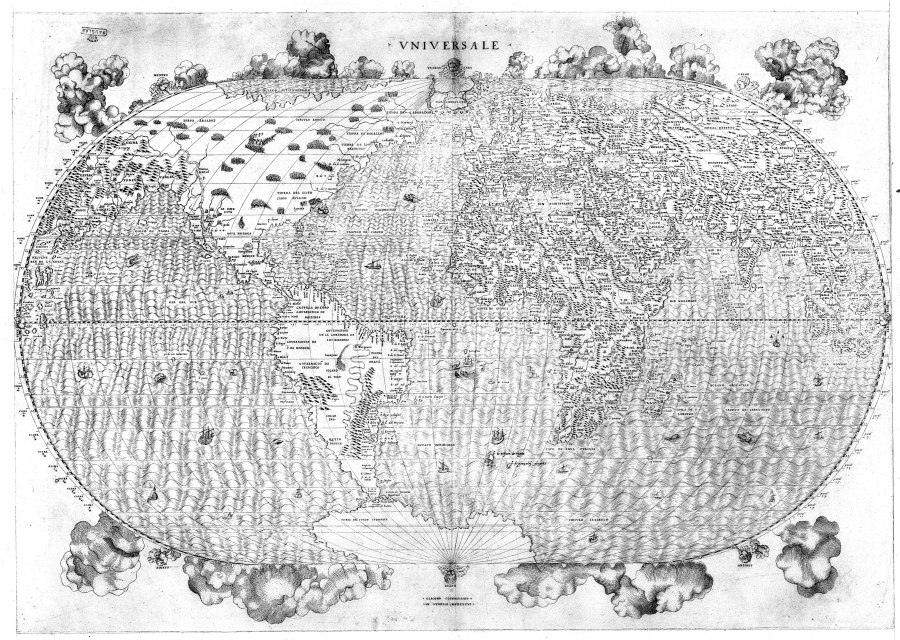

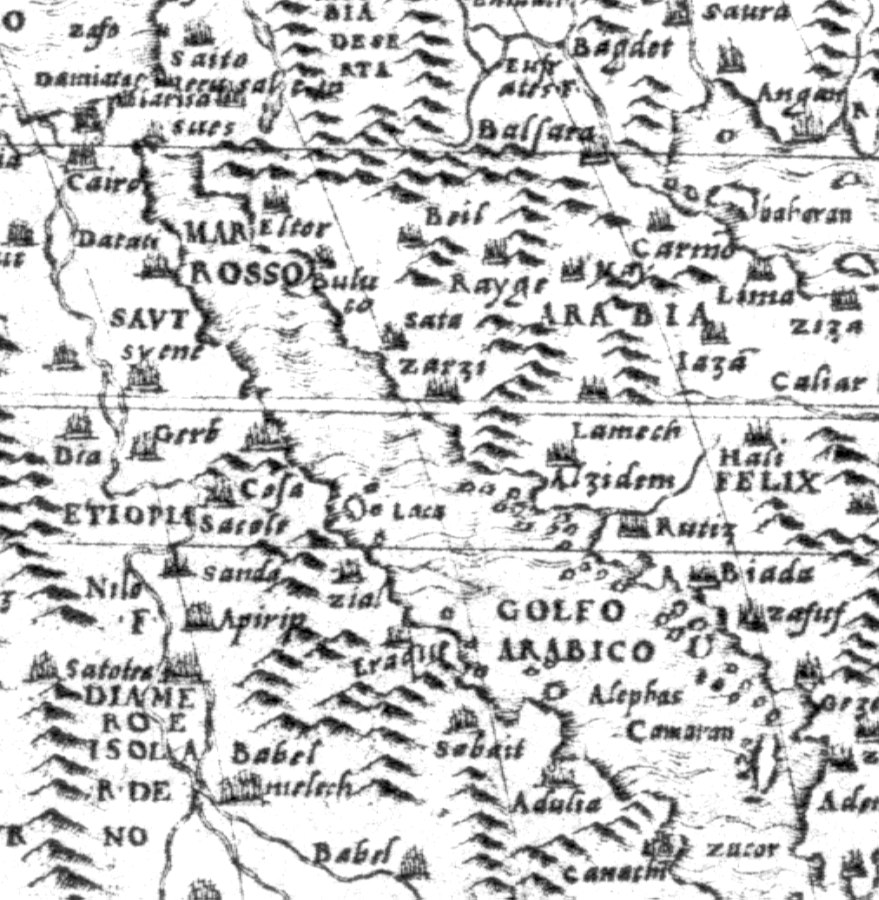

Fig. 5dp-09. Detailed world map by Giacomo Gastaldi, Venice, the alleged year 1546. The modern Red Sea between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula is indicated as “Mar Rosso”. Taken from [1459], Plate XXXVI, No. 121.

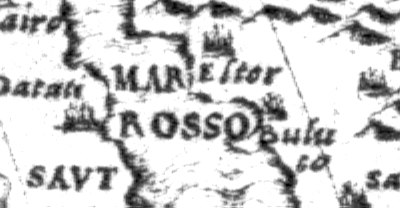

Fig. 5dp-09a. Close-in of a fragment of the map by Giacomo Gastaldi allegedly dating from 1546. The modern Red Sea is called “Mar Rosso”. Taken from [1459], Plate XXXVI, No. 121.

Fig. 5dp-09b. Another close-in of Giacomo Gastaldi’s map, magnified further. We see the “Russian Sea”. Taken from [1459], Plate XXXVI, No. 121.

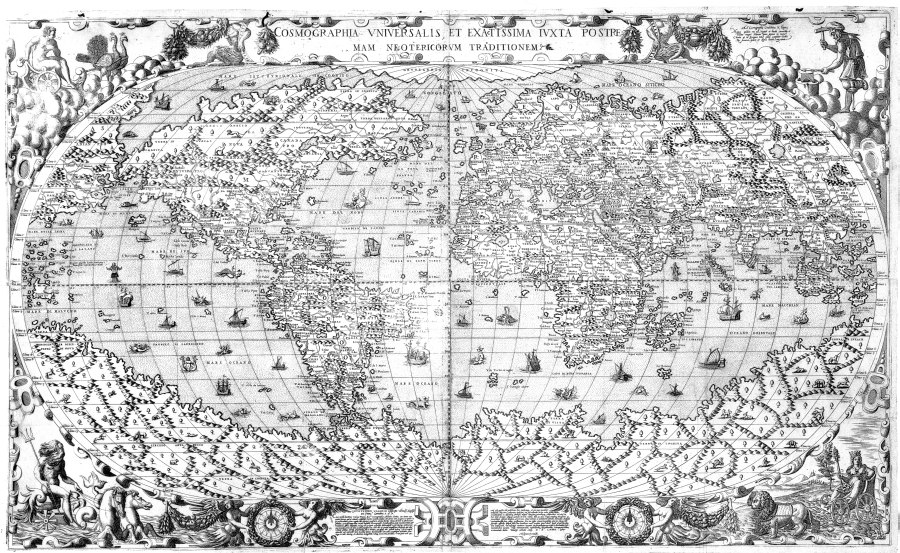

Fig. 5dp-10. A detailed world map by Gianfrancesco Cammoccio, Venice, the alleged year 1569. The modern Red Sea between Africa and Arabia is referred to as “Mare Rosso”, or “Russian Sea”. Taken from [1459], Plate XXXVII, No. 125.

Fig. 5dp-10a. Close-in of a fragment of the Venetian map by Gianfrancesco Cammoccio allegedly dating from 1569. We see the Red Sea indicated as “Mare Rosso”. Taken from [1459], Plate XXXVII, No. 125.

Fig. 5dp-10b. The same fragment of the map by Gianfrancesco Cammoccio with the Red Sea, or the “Russian Sea”, under greater magnification. Taken from [1459], Plate XXXVII, No. 125.

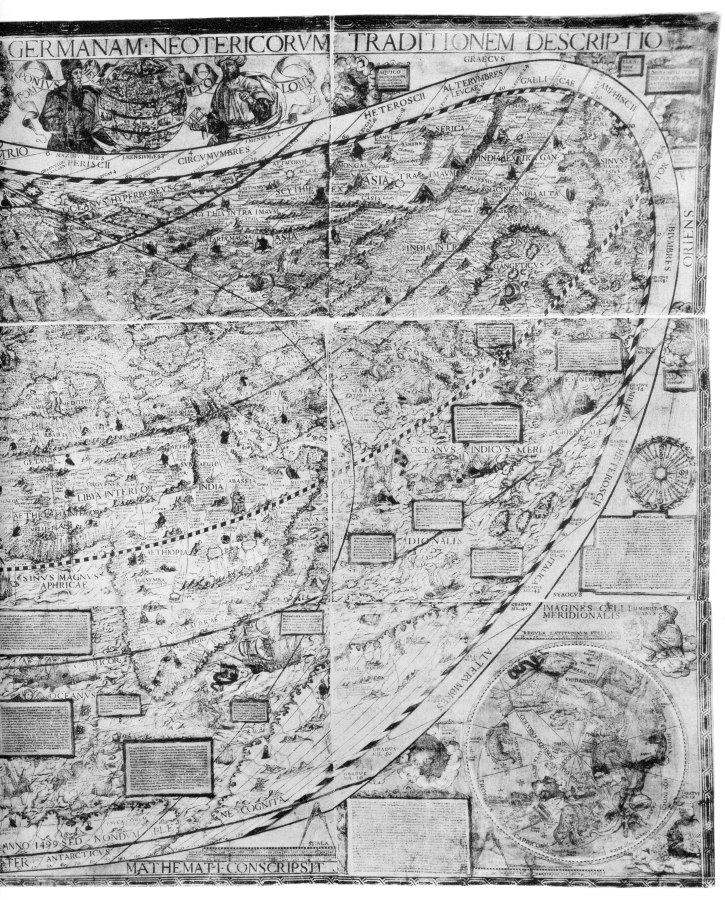

Fig. 5dp-11. Eastern part of the detailed world map compiled by Caspar Vopell, Venice, in the alleged year 1558. Much of the information found on this map contradicts Scaligerian history very blatantly indeed – however, our reconstruction makes it all look perfectly normal. For instance, we see the legend “India” set in large letters and placed at the very centre of Africa. Taken from [1459], Plate XXXIX, No. 111.

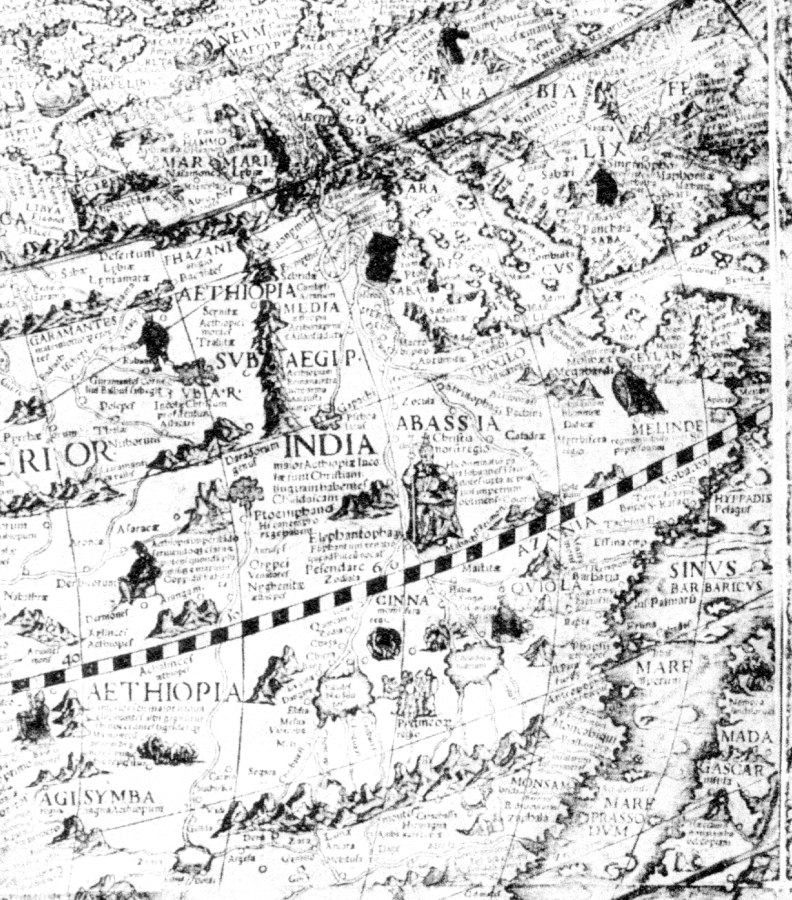

Fig. 5dp-11a. Close-in of a fragment of Caspar Vopell’s map with India at the centre of Africa. The corresponding legend is as follows: “India major . . . Christiani . . .” – apparently, “Greater India, a Christian country”. Unfortunately, we haven’t managed to decipher the rest of the legend due to the low resolution of the photograph. Taken from [1459], Plate XXXIX, No. 111.

Fig. 5dp-11b. Another close-in of a fragment of Caspar Vopell’s map with India at the centre of Africa under greater magnification. To the right of the legend “India” we see a king on his throne who holds a sceptre topped by a large Christian cross. Taken from [1459], Plate XXXIX, No. 111.

Fig. 5dp-12. The mummy of the Egyptian Pharaoh Seti I. According to our reconstruction, the Egyptian Pharaohs buried in the Valley of the Kings were really the Czars of the Great Empire, a mediaeval state whose capital was in the Vladimir and Suzdal region of Russia in the XIV century and later. Mark the explicitly Caucasian features of the Pharaoh’s face – his Slavic origins seem very plausible indeed. Incidentally, his tomb in the Valley of the Kings is one of the most lavish ones. Its ceiling is decorated with a zodiac that hasn’t been deciphered or dated yet. Taken from “Mummies” by Philip Steele (Moscow, Machaon, 1999), page 74. The authors are referring to the Russian edition of the book published by King Fisher Publishers, New York, in 1998.

Fig. 5dp-13. Stone masonry near the entrance to the Karnak Temple in Egypt. The eroded parts of the huge stone blocks reveal chaotic layer curves. Such amorphous structure of the stone implies that the block didn’t come from a quarry (in which case the layers would be parallel), and can be identified as a concrete casting made in several stages, hence the erratic nature of the layers. Liquid concrete was poured into a mould and hardened portion by portion. Photograph taken in 2000.

Fig. 5dp-14. Two effigies of the deceased Pharaohs in the Temple of Karnak, Egypt. Both have their arms crossed on their chests, as is customary for Christian burials. Both are holding Coptic Christian crosses with loops at the top, or “ankhs”, in either hand. Photograph taken in 2002.

Fig. 5dp-15. The Colossi of Memnon in the beginning of 2002. The right colossus is inside scaffolding – it is being restored. And yet we are told that the “ancient” Egyptian constructions have stood fast for thousands of years. If this is the case, how could it be that they started to erode at such a rate only recently? Could it be that their age really isn’t all that great, and that the current erosion rate is perfectly normal? Photograph taken in 2002.

Fig. 5dp-16. The hills in the Valley of the Kings (Egypt, Luxor). The stone is so soft that it crumbles by itself with time. It is a very convenient material for grinding into powder, which can be used for making concrete blocks subsequently. It is also completely impossible to cut a large stone block from these rocks – nevertheless, each of the numerous “ancient” Egyptian temples located in this area was built of such blocks. Photograph taken in 2002.

Fig. 5dp-17. Valley of the Kings in Egypt, near Luxor. Egyptian Pharaohs were buried in this canyon, which is hidden from everyone’s sight and can only be approached via a single road built among the rocks. According to our reconstruction, the deceased weren’t mere rulers of Egypt, but rather Khans, or Czars, of the entire Great Empire in the Middle Ages. The imperial capital was in Russia between the XIV and the XVII century, until the dissolution of the Empire. Photograph taken in 2002.

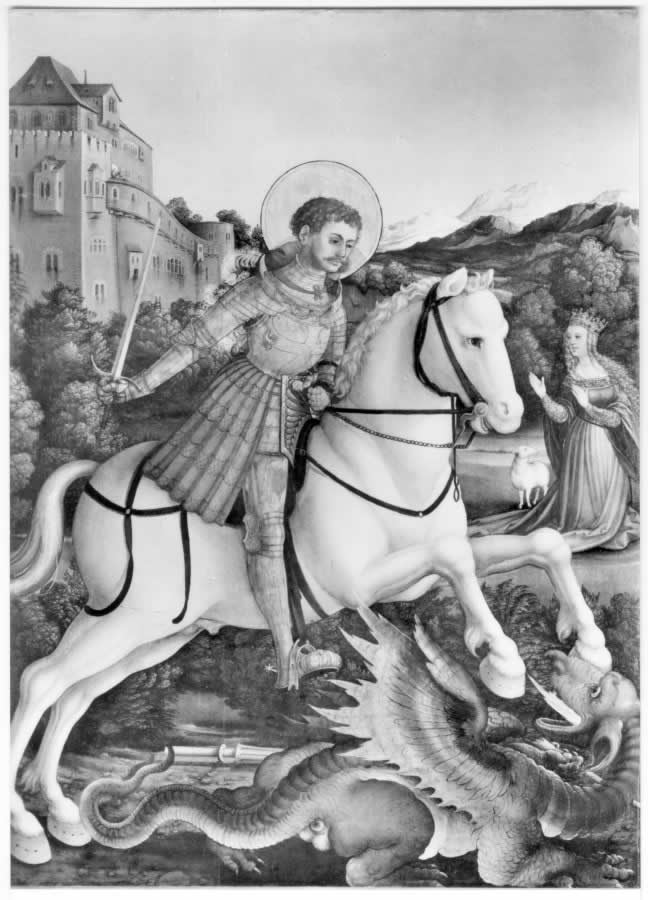

Fig. 5dp-18. “St. George Fighting the Dragon” by Martin Schaffner. Once again we see the saved princess, just like Andromeda in the legends of the “ancient” Perseus. Mark the curly hair of St. George – as we have already pointed out, this detail is very typical for most works of art that portray St. George. See CHRON5, Chapter 12:11.4 for more details. Taken from the following postcard: Augsburg Staatsgalerie. Aufnahme Helga Schmidt-Glassner. Deutscher Kunstverlag, München & Berlin (146).

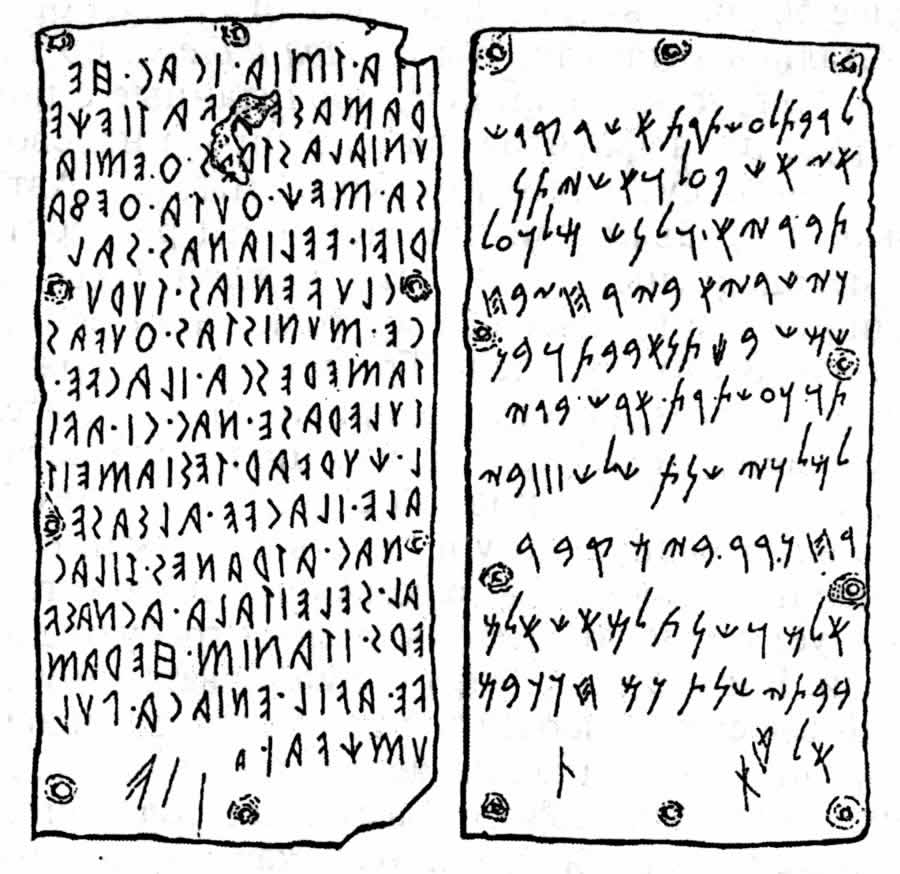

Fig. 5dp-19. “Famous golden tablets from Pyrga with parallel inscriptions in Etruscan and Phoenician. The translators have failed to reach a consensus on this issue”. Taken from “Veneti: Ancestors of the Slavs” by Pavel Tulayev (Moscow, “Byelye Alvy”, 2000), pages 70-71. Already in the XIX century the research of such prominent scientists as A. D. Chertkov and F. Volanski revealed that many Etruscan texts can be deciphered with the aid of Slavic languages. However, no details of such research are ever made public. See more on this subject in CHRON5, Chapter 15.

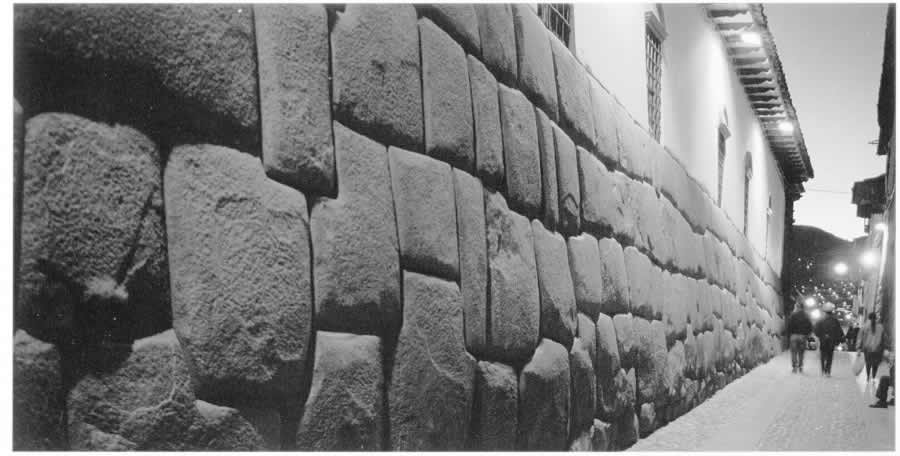

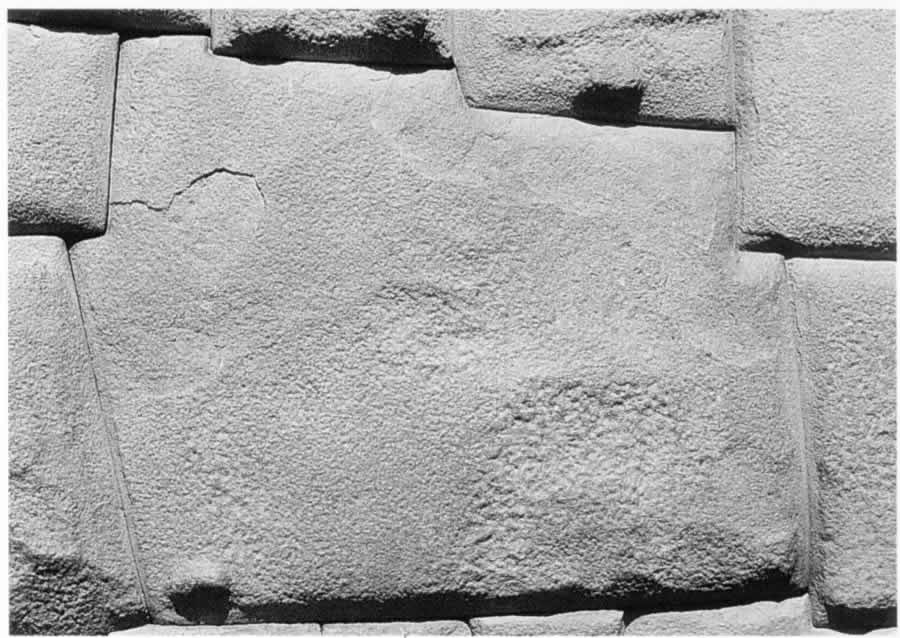

Fig. 5dp-20a. The wall built by the “ancient” Incas in the Peruvian city of Cuzco (Calle Hatunrumiyoq). It is made of large blocks that fit together very tightly – local guides never tire of emphasising that one cannot get so much as a blade of a knife between adjacent blocks. Historians and archaeologists compete in inventing various “theories” of great ingenuity in order to explain how the “ancient” Incas managed to “cut and fit together” enormous stone blocks of immense weight. Even more elaborate theories are constructed to explain how stone blocks of this size could be elevated to the top of the construction. Authoritative sources are trying to convince us that each such block was “the fruit of many months of labour”. However, the new information that we have about construction works in the Middle Ages makes it rather easy to explain all the above. Such walls of Incan cities (and even more monumental ones) were made of concrete blocks. The technology must have been as follows: sacks of rough cloth were filled with liquid concrete and placed inside wooden frames. The sacks assumed the necessary shape, and the concrete clung to the existing blocks, already solid, without any spaces left in between. The external part of the sack would then be removed; smaller pieces of fabric must have disintegrated without affecting the masonry. This theory was voiced by S. M. Bourygin after he became familiar with our conception of the New Chronology and the research of I. Davidovich in the field of geopolymeric concrete (see CHRON5, Chapter 19:6). S. M. Bourygin supplied us with numerous photographs of such walls common for many Peruvian cities. Taken from Alexandra Arellano’s book entitled "All Cuzco. Peru". - Fisa Escudo de Oro. Centre of Regional Studies of the Andes "Bartolome de las Casas", Lima, Peru. Instituto de Investigacion de la Facultad de Turismo y Hotelria, Universidad San Martin de Porres, 1999, page 5.

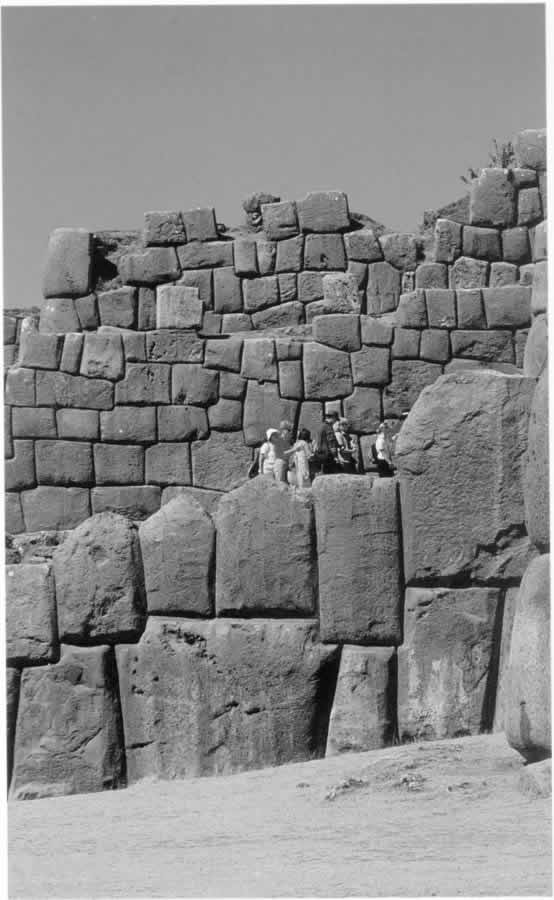

Fig. 5dp-20c. Tall wall of huge stone blocks that fit together perfectly well. Cuzco, Sacsayhuaman, Peru. The wall was built by the “ancient” Incas. As we have explained above, the technology must have involved the placement of cloth sacks with liquid concrete between wooden boards that defined the general shape of the wall. When the concrete hardened, the blocks assumed an ideal shape. Taken from Alexandra Arellano’s book entitled "All Cuzco. Peru". - Fisa Escudo de Oro. Centre of Regional Studies of the Andes "Bartolome de las Casas", Lima, Peru. Instituto de Investigacion de la Facultad de Turismo y Hotelria, Universidad San Martin de Porres, 1999, page 27.

Fig. 5dp-21. Joseph Justus Scaliger (1540-1609). This portrait differs from another old portrait of Scaliger (reproduced in CHRON1, Chapter 1:2). Taken from the catalogue under the following title: “The 30-year War. The Splendour of Europe. The Renaissance. Humanism. Enlightenment”. Published by the V. T. Kozlov Regional Public Fine Arts and Culture Support Foundation, Moscow, 2001 (see page 44).

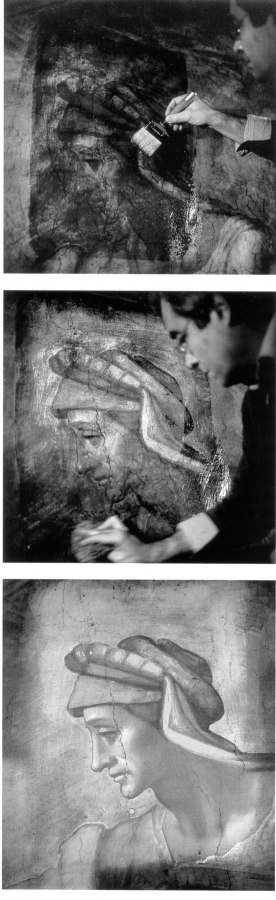

Fig. 5dp-22. Ever since the decline of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire in the XVII century and the radical revision of history that followed, we have been deliberately fed the myth that historical realities known to us today have always been this way. First and foremost, the myth about the world changing very slowly was a political necessity: the new rulers of the Reformation epoch were in need of “substantial proof” in order to back their claims for the throne, tracing their lineage back to times immemorial. This myth of “antiquity and rigidity” expanded to include the surviving historical artefacts. The makers of Scaligerian history dated the works of mediaeval writers, artists and craftsmen to deep antiquity, assuring everyone that the works in question have been around for hundreds and even thousands of years without suffering much damage inflicted by age. However, this claim has been proven preposterous by the destruction rate of mediaeval artefacts registered today. Only a very limited number of professional restorers are aware of just how fast the ancient works of art (paintings, frescoes, statues etc) darken and erode. Museum visitors usually see the end result of the restorers’ efforts, completely unaware of their being confronted by embellished and “revamped” history. In order to illustrate our point, we reproduce a rare photograph where one sees the actual process of Michelangelo’s XVI century Sistine Chapel frescoes being restored at the end of the XX century. The lighter part of the artwork represents the results of the restorers’ efforts. The rest, which looks much darker, corresponds to the natural condition of Michelangelo’s frescoes after the passage of some time (one must also bear in mind that the restoration works in question were by no means the first ones conducted in the Sistine Chapel. It has to be said that the actual conception of renovation is highly ambiguous per se. Today such endeavours are seen as “noble efforts aimed at the preservation of humanity’s cultural legacy” – however, more often than not this translates as the replacement of the dilapidated original by a blatant replica created by our contemporaries in accordance with the guidelines of Scaligerian history. It would be much better for the preservation of historical truth (and a great deal more honest to boot) to preserve the ancient artefacts in the exact same condition that they had when they were discovered. Renovation, which is often de facto rendered to painting an “ancient fresco” anew, filling the gaps with the products of one’s own artistic imagination, has every reason to be regarded as forgery. Making the past look “better” is an act of forgery at the end of the day, no matter how noble the motivation. Taken from “The Sistine Restoration. A Renaissance for Michelangelo”, an article by David Jeffery published in the National Geographic magazine, Vol. 176, #6, December, 1989 (page 696).

Fig. 5dp-23. The inculcation of the myth about the “conservative nature of the ancient history” and the allegedly slow evolution of civilizations by the mutinous reformists of the XVII-XVIII century had a very simple goal of making the freshly emerged independent states that evolved from former fragments of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire look old and dignified, with ancestry traceable to the very deepest antiquity. The myth of “ancient artefacts” remaining miraculously intact for many centuries on end was certainly very useful for that purpose. However, modern experience demonstrates that paintings, frescoes, sculptures, buildings etc erode at a considerable pace. We reproduce a rare photograph that demonstrates the restoration of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. The lighter part above is what the restorers painted in lieu of the original eroded paint layer. The rest of the ceiling is virtually black. If it weren’t for the restorers, modern visitors of the Sistine Chapel would see nothing but darkened plaster covered in blurry blotches. And yet we are being told that the “ancient” works of art have reached us in their primordial condition from the immense depths of Scaligerian millennia. Therefore, the bright colours of Michelangelo’s frescoes and the numerous works of ancient art as known to us from countless reproductions can actually be credited to the modern restorers. The exact condition of the ancient originals usually remains well beyond the scope of public attention. This state of affairs is very salubrious for the tourist industry – the more attractions, the more tourists (which translates as more money). Taken from “The Sistine Restoration. A Renaissance for Michelangelo”, an article by David Jeffery published in the National Geographic magazine, Vol. 176, #6, December, 1989 (page 696).

Fig. 5dp-24. As we have already mentioned (see CHRON1, Chapter 1:13.3), the general public is puzzled about the rapidly deteriorating condition of the allegedly ancient works of art, sculptures, paintings and buildings, which is seen as a recent phenomenon. After all, Scaligerian history tries to convince us that these artefacts have remained intact for hundreds and even thousands of years. The suggested explanation is the allegedly perilous influence of the modern industry. However, the real reason is different. As we realise today, the Scaligerian millennia are a phantom; the erosion rates have always been rather high. We reproduce a rare photograph of restoration works in the Sistine Chapel as proof. The darkening and dilapidation of the frescoes make it impossible to make out any details at all. The “reconstructed originals” shown to us today were all painted by the modern restorers. We have no means of estimating the reproduction accuracy. The very idea of restoring old artwork (as well as making replicas of antiques) came into being during the Reformation, stimulated by the need of creating a new picture of the past that would meet the needs of the new rulers. Therefore, the most valuable ancient documents and works of art are the ones that have escaped the caring hands of the restorers. Semi-dilapidated originals are much less of a sight than the exquisite replicas – however, they are a lot more likely to be authentic. Let us reiterate that the bright colours of the Sistine frescoes have nothing to do with Michelangelo himself, which is highly deplorable. His art fell prey to relentless time. What we see today is the art of the restorers “based on Michelangelo’s motifs”. Taken from “The Sistine Restoration. A Renaissance for Michelangelo”, an article by David Jeffery published in the National Geographic magazine, Vol. 176, #6, December, 1989 (page 696).

Fig. 5dp-28. Ancient wooden Church of Lazarus Risen (from the Monastery of Murom, late XIV – early XV century). Nowadays it is part of the Kizhi ensemble on an island in Lake Onega. Its style is typical for the ancient Russia (also known as the Horde and the “Mongolian Empire”), and is easily identifiable as the famous Gothic style familiar to us from the architecture of the Western European cathedrals (see CHRON4, Chapter 14:47). Postcard from the collection by B. Savik and V. Parkkinen called “Kizhi. Open Air Museum”. See CHRON4, Chapter 14:47 for more details.

Fig. 5dp-29b. The Pokrov Church of 1764. Isle of Kizhi, Lake Onega. The entrance to the church is on the first floor, not the ground floor – this is a typical trait of the “ancient” Mongolian churches of Russia, or the Horde. It was only after the drastic reform of religious customs instigated by the Romanovs in the XVII century that the architecture of the Russian churches transformed into the “Greek style”, fallaciously declared ancient. Postcard from the collection by B. Savik and V. Parkkinen called “Kizhi. Open Air Museum”. See CHRON4, Chapter 14:47 for more details.

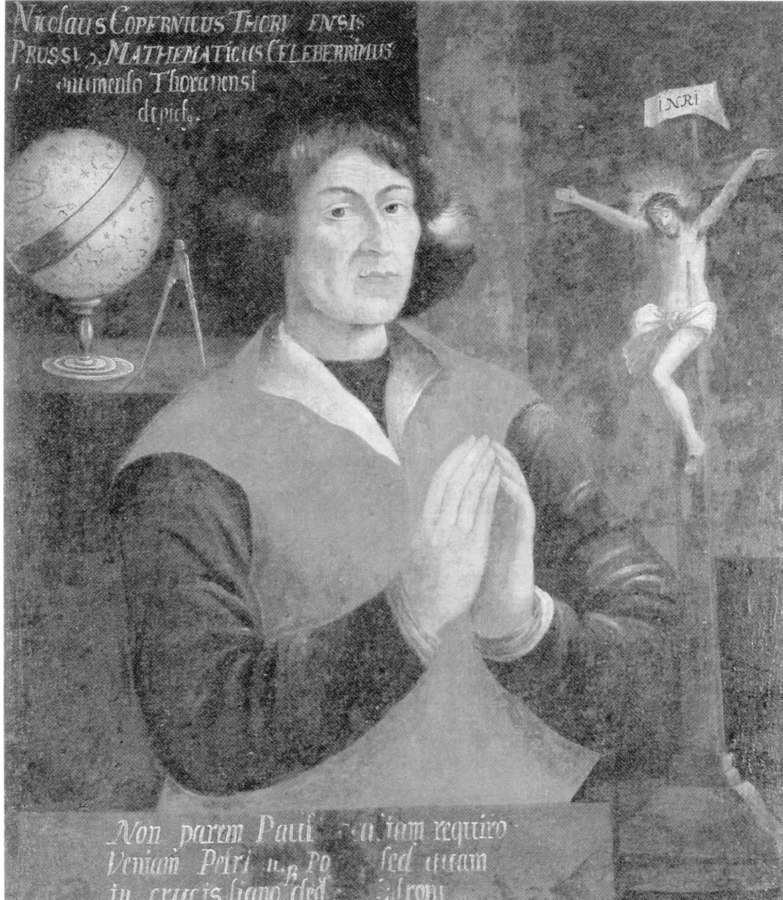

Fig. 5dp-32. Portrait of Nicholas Copernicus (who is presumed to have lived in 1473-1543) made by an anonymous artist in the alleged year 1600 (kept in the library of the Leipzig University). The portrait is ostensibly different from the other old portraits of Copernicus that we reproduced in CHRON3. The legend on the portrait begins as follows: “Nicolaus Copernicus Thorv ensis Prussi . . .”. Mark the term “Prussi” as applied to Copernicus. Taken from “The Parsimonious Universe. Shape and Form in the Natural World”. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1996 (page 59).

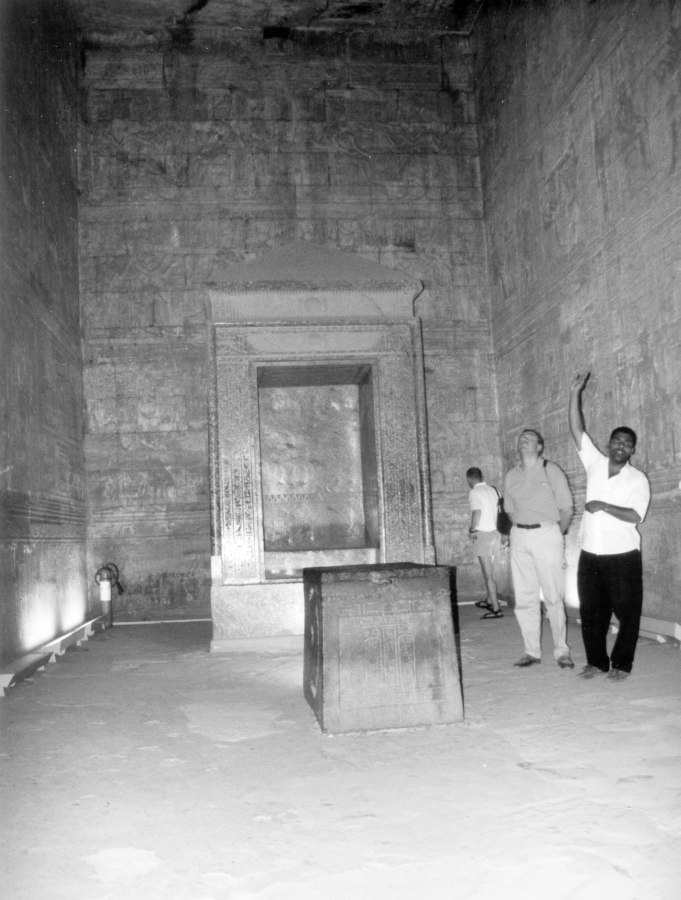

Fig. 5dp-34. Altar room of the “ancient” Egyptian Temple in Edfu. Its construction coincides with that of the Christian altar rooms, complete with the so-called “royal gates” and the location of the altar. On the left and the right of the “royal gates” there are two doors leading to side-chapels. Therefore, the sanctum sanctorum of the Egyptian temple was a spitting image of the altar-rooms of Christian churches. Photograph taken in July 2002.

Fig. 5dp-35. “Ancient” Egyptian stone depicting Christian crosses of the exact same shape that we’re accustomed to today. The stone was discovered during the excavations of the “ancient” Egyptian temple of Edfu. Therefore, the temple in question was in fact a Christian church – and by no means a clandestine tabernacle of the sort that modern historians are very fond of describing at great length. The religious rituals were obviously conducted openly here, which is obvious from the size of the enormous stone effigies. In this case the halfway rounded stone has a diameter of 150 cm – a large and massive Christian symbol with nothing clandestine or secretive about it. Photograph taken in July 2002.

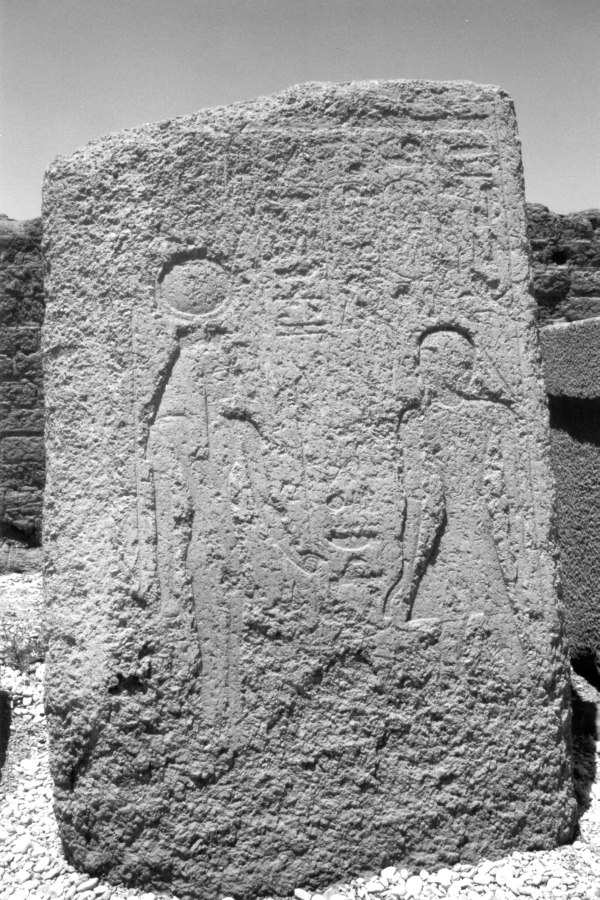

Fig. 5dp-36. Low quality concrete granite block with some “ancient” Egyptian symbols embossed on it. Located in the court of the “ancient” Egyptian temple of Dendera; found on the site during excavations. In this particular case the builders chose a poor quality binding solution, either by mistake or due to insufficient experience. The pieces of granite fall apart at the slightest touch as a result. This specimen proves it irrefutably that geopolymeric concrete was used very widely in the “ancient” Egypt as a construction material. Photograph taken in July 2002.

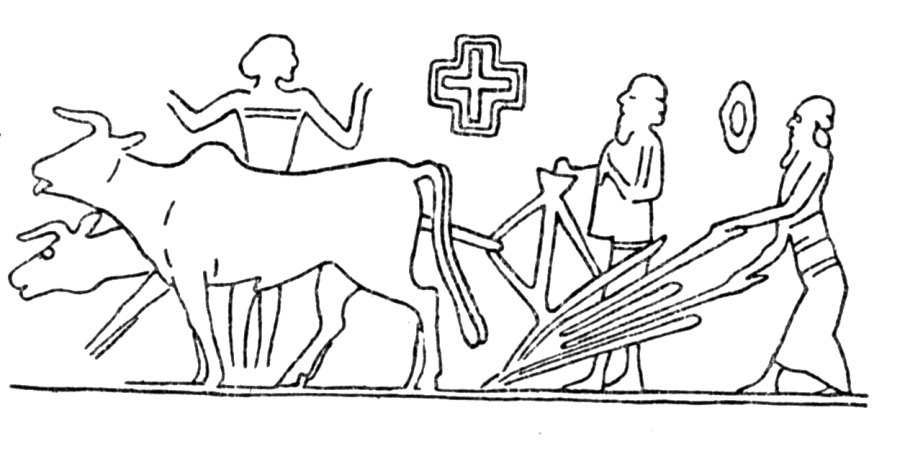

Fig. 5dp-37. “The image of a sowing plough embossed on clay with a cylindrical matrix (around 1400 B. C., Mesopotamia). Taken from The Concise Soviet Encyclopaedia, Moscow, 1928, Volume 1, pages 159-160. However, what we see on this “antediluvian” embossment is a typical Christian cross. The finding is therefore unlikely to predate the XII century A. D.

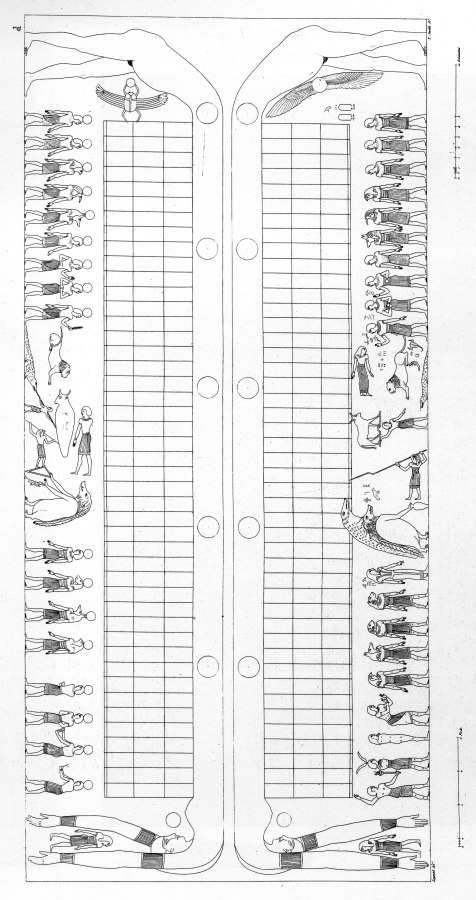

Fig. 5dp-38. Drawn copy of the Coloured Theban Zodiac discovered in the Luxor Valley of the Kings. It was found in the early XIX century, during the Egyptian campaign of Napoleon. The drawn copy was made by the Napoleonic artists. In CHRON3 we have already reproduced the coloured copy of this zodiac contained in the same “Napoleonic” Egyptian album ([1100]). The black and white version reproduced herein gives one a better view of certain minor details pertaining to this important zodiac. Let us remind the reader that our research of the Theban Zodiac revealed the date ciphered therein to be 5-8 September 1182 A. D., qv in CHRON3, Chapter 18:3. In CHRON3 we use the abbreviation OU for referring to this zodiac. Taken from [1100], A. Vol. I – Plate 96 (left page).

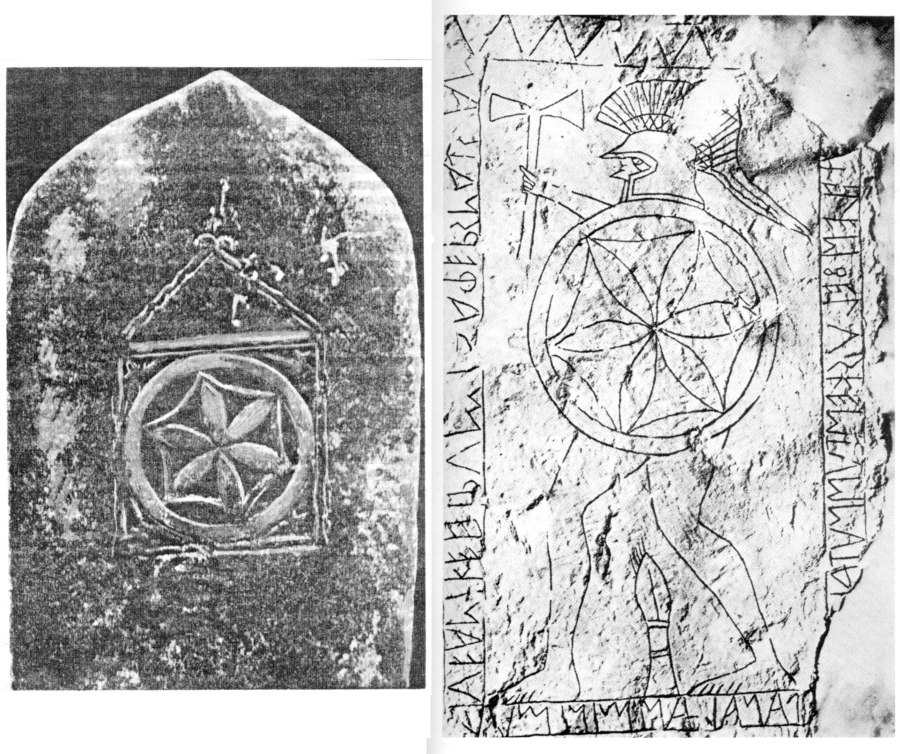

Fig. 5dp-39. On the right we see the memorial Etruscan stele of Avles Feluske, allegedly dating from the V century B. C. (Vetulonia, Italy). Kept in the Florentine Museum of Archaeology. Taken from [1410], page 247; see also [574], page 114. On the left we reproduce the rear side of a XVI century stone monument from the village of Middle Aty in Tartarstan, Russia. This photograph was reproduced in G. V. Yousoupov’s work entitled “An Introduction to the Bulgar and Tartar Epigraphy” (1960), page 152. We are using a reproduction of this extremely valuable snapshot taken from a more recent publication of Nurikhan Fattakh entitled “Language of the Gods and the Pharaohs”, Kazan, Tatarskoye Knizhnoye Izdatelstvo, 1999 (page 271). The two ornaments are virtually identical to each other – the “ancient” Etruscan stele reveals itself to be a relation of a Tartar monument of the XVI century located in Russia. We see a six-pointed star circumscribed by a hexagon and then also a circle. On the Etruscan stele the “Star of David” (apparently a religious symbol used by all Orthodox Christians at some point) decorates the shield of an Etruscan warrior. According to our reconstruction, such close proximity between the Tartar symbols and their Etruscan counterparts can be explained by the colonization of the Western Europe (Italy in particular) by the Horde in the XIV century, whose vestiges were later ascribed to the “ancient Etruscan civilization”.