Part 1.

Russia as the centre of the “Mongolian” Empire and its role in mediaeval civilization.

Chapter 1.

“Peculiar” geographical names on the maps of the XVIII century.

Zoubritskiy. “History of Russia”.

Quotation given in accordance with [388], page 6.

1. Introduction.

Let us briefly remind the readers of the research results related in CHRON4. According to our hypothesis, the Horde, or the Army, had not been any foreign force that invaded Russia from abroad, but rather the regular Russian army, which had been an integral part of the ancient Russian state.

1) The “Tartar and Mongol yoke” was merely a period of military rule in Russia, which has never been conquered by any foreign force.

2) The supreme ruler was the military leader, known as the Khan or the Czar, whereas the civilian rulers, or the princes, were in charge of the cities and provinces, responsible for collecting the tax that went to support the Russian army.

3) Ancient Russia can therefore be regarded as a unified state – the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, which had a regular army of professional warriors (the Horde). There was also the civilian part, with no regular army – all the military personnel was serving in the Horde.

4) The Horde, or the militarized Russian Empire, existed between the XIV and the early XVII century. Its history ends with the notorious Great Strife, when the Russian Czars of the Horde, the last one being Boris “Godunov”, were massacred in the course of the civil war. The Horde, or the imperial army, was crushed by the opposition, or the “pro-Western party”. The throne was usurped by a radically new dynasty of the pro-Western Romanovs, who had also seized ecclesiastical power (installing Filaret as the new Patriarch).

5) The new dynasty was in need of a “new history” required as an ideological justification of its reign – after all, the Romanovs acted as usurpers insofar as the old history of Horde Russia was concerned. They needed to introduce a radically novel interpretation of the previous period in Russian history. One must admit that they managed to do it aptly enough – they distorted the entire history of Russia beyond recognition, keeping most of the actual facts intact. The history of Horde Russia, whose populace had been divided into civilians and professional warriors (the actual Horde), was declared to have been the epoch of a “foreign conquest”. As a result, the Horde, or the Russian Army, transformed into a host of foreign invaders from some mysterious distant land under the quills of Romanovian historians.

2. The meaning of the word “Mongolia” as used by the authors.

In the present book (likewise CHRON4) we often use the words “Mongolia” and “Mongols”, inevitably confusing the readers despite our intention. The problem is that these words are already used in an altogether different meaning, referring to a certain racial type known as “Mongoloid”.

However, our research demonstrates that the mediaeval meaning of the word had differed from the modern completely – Mongolia, or Tartar Mongolia (Tartary) was the name of the mediaeval Russian empire, which we also call Horde Russia. It is similar to the terms “Russian Empire”, “Soviet Union” and “Russian Federation” in the sense that its populace has always been multinational – the Slavs have always coexisted with other ethnic groups.

As we frequently mentioned above, the word “Mongolia” translates from Greek as “The Great Empire”, or “The Great Kingdom”. Alternatively, it may be derived from the Russian words for “many”, “might” and “multitude” – “mnogo”, “moshch” and “mnozhestvo”, respectively. One must constantly bear it in mind that a great many terms have changed their meanings over the years. We couldn’t think of another word to replace the term “Mongols”, which translates as “the great ones”, although it may have been expedient so as not to confuse the readers who are naturally accustomed to the modern meaning of the word “Mongol”.

We must therefore urge the readers to keep this in mind all the time – we use the words “Mongol” and “Mongolian” in their mediaeval meaning exclusively, referring to the Great Empire of the Middle Ages whose centre was in Russia, founded by the Russians as well as numerous other ethnic groups that populated its territory.

From the one hand, we are referring to the same phenomena as modern historians – the Great Mongolian Empire with its centre in Russia, or the Golden Horde on the Volga. We agree that it had really existed – however, unlike the historians of the Romanovian school, we suggest that Great = “Mongolian” Empire was in fact Russian, built by the Slavs and the Turkic peoples (the Russians and the Tartars, for instance).

As for the court historians of the Romanovs, they declared the “Mongolian” Empire to have been founded as a result of a military conflict between these peoples, which had resulted in the victory of the Tartars over the Russians. We are of the opinion that the Tartars and the Russians had never fought against each other, with the exception of the internal civil wars, wherein each of the conflicting parties included representatives of both ethnic groups.

Church Slavonic had been the official language of the Great = “Mongolian” empire. We have made this conclusion since we never managed to find any official imperial documents written in a Turkic language, qv in CHRON4. However, there were at least two spoken languages – Russian and Tartaric. It wasn’t just a case of the Tartars speaking Russian, the way it is today – the Russians had also spoken Tartaric, as we demonstrate below, citing Afanasiy Nikitin’s “Voyage”, for instance. See also CHRON4, Chapter 13:3.1.

The regions where Islam had prevailed after the schism adopted Arabic (and later Turkic) as their official language.

3. The Kuban Tartars as the Kuban Cossacks on the maps of Russia dating from the epoch of Peter the Great.

In the present section we relate a number of valuable observations made by A. V. Nerlinskiy. We would like to express our gratitude to him. A. V. Nerlinskiy has conducted a research of antique Russian military maps, in particular – the naval charts kept in the Navy Archive of St. Petersburg.

Let us turn to the atlas entitled “Russian Naval Charts of 1701-1750. Copies from originals” published by Captain Y. N. Biroulya in St. Petersburg in 1993 ([73]). As Y. N. Biroulya writes in the introduction, the collection is comprised of “the charts that demonstrate the evolution of naval cartography over a period of 50 years, from the first charts compiled with the participation Peter the Great to the more recent ones belonging to ‘the younglings from Peter’s nest’”.

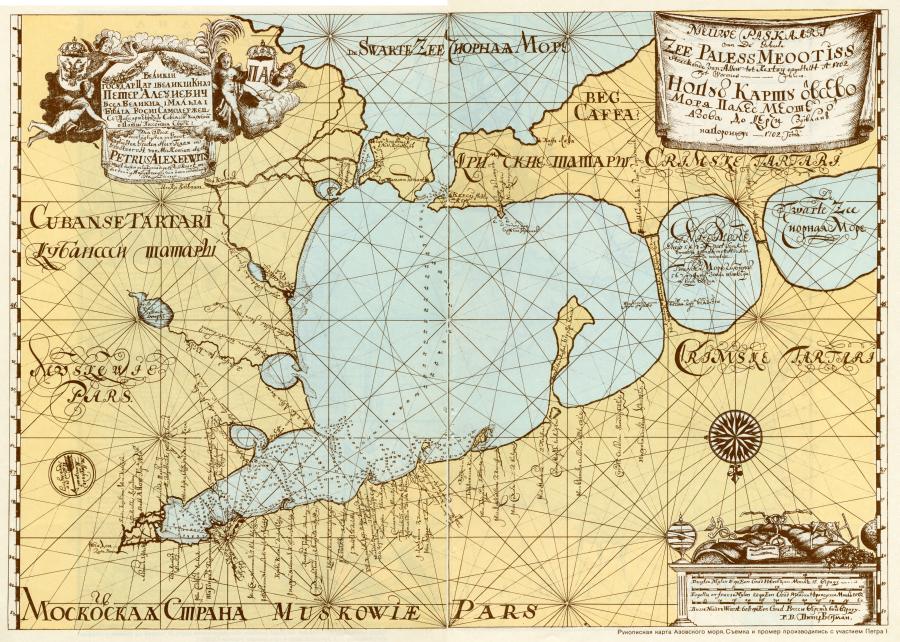

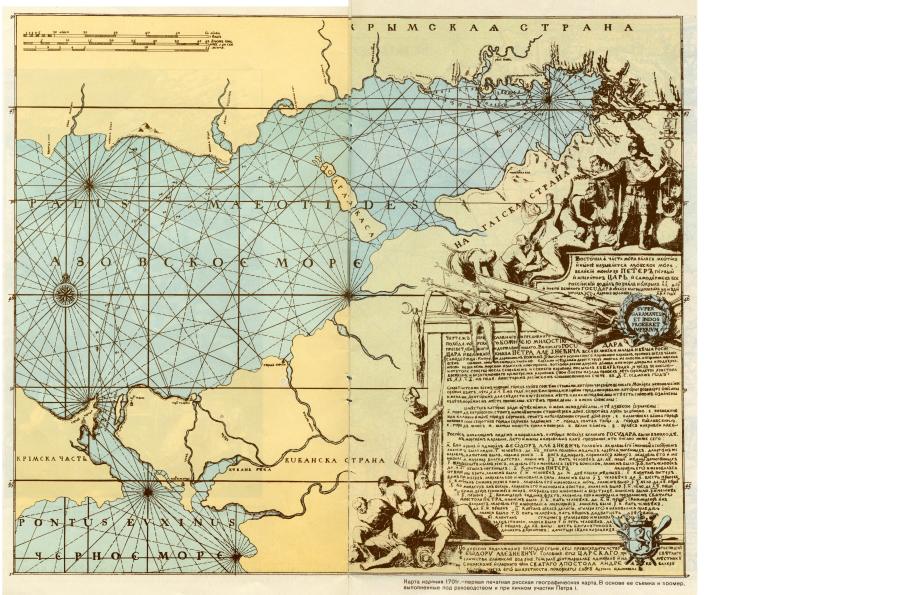

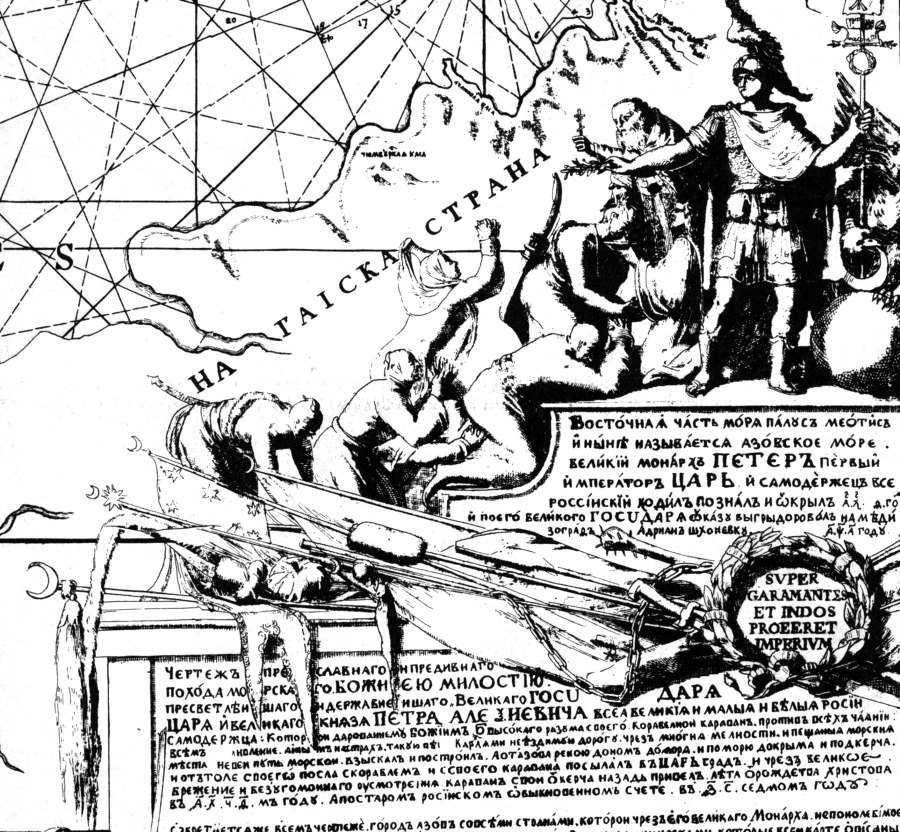

We shall turn to the drawn map of the Azov Sea compiled in 1702. “Observations and measurements performed with the participation of Peter the Great” ([73]). See fig. 1.1.

First of all, let us point out that the map is inverted as compared to the modern tradition, with the North at the bottom and the South at the top. As we mentioned in CHRON1, Chapter 1:10.3, such orientation of maps might strike the modern viewer as uncanny, but it was used commonly in “ancient” and mediaeval cartography. Inverted maps aren’t quite as innocuous as they may seem initially. Imagine reading a chronicle that mentions geographical locations of certain places. If we know nothing about the kind of map used by the scribe, we may easily confuse directions and come up with a distorted reconstruction of the past. There are actual examples of such confusion, qv in CHRON1 – Babylon gets confused with Rome, France is mistaken for Persia etc.

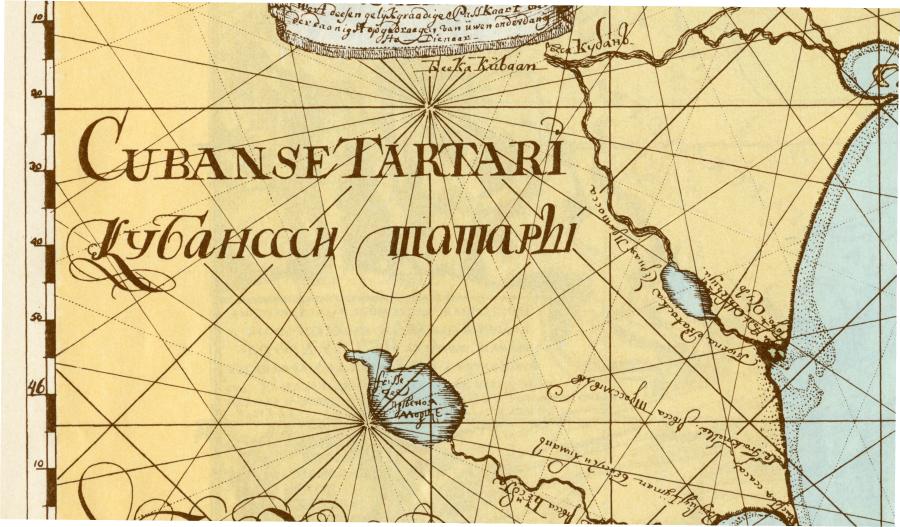

Peter’s map indicates the presence of Crimean Tartars in Crimea. There is nothing surprising about this fact, of course. However, another area (which has always been populated by the Kuban Cossacks) is marked as the home of Kuban Tartars, qv in fig. 1.2. The legend is translated into Latin as “Cubanse Tartari”, as seen on the same illustration. Incidentally, the lower-case letter «к» as seen in the Russian version is a spitting image of the double “с” – we see even in the epoch of Peter the Great different Cyrillic characters used to resemble each other in writing, and very strongly so, which could be very confusing, especially for foreigners.

Thus, Peter the Great and his cartographers must have thought it perfectly normal to use the word “Tartars” for referring to the Cossacks. This fact concurs perfectly with our reconstruction of the ancient Russian history, qv in CHRON4. This can only mean that the synonymy of the words “Tartar” and “Cossack” was perfectly commonplace in the epoch of Peter the Great and routinely referred to on naval charts.

Possible counter-argumentation may be formulated as follows: Kuban Cossacks are the descendants of the Zaporozhye Cossacks, who had migrated to Turkey in the reign of Peter and returned to Russia in the XVIII century, settling in the Kuban region. However, if the region in question had once been populated by the “Kuban Tartars”, how come they disappeared without a trace? Had these “Tartars” really been Tartars in the modern sense of the word, the population of Kuban would become mixed after the advent of the Cossacks, who settled there in the XVIII century. This happened in the Caucasus, conquered by Russia in the early XIX century. What has become of the Kuban Tartars?

We are of the opinion that Kuban has always been populated by the Cossacks, before and after the migration of their cousins from Zaporozhye. Romanovian historians must have conducted an enormous body of work in order to vanquish all such “harmful” traces of the authentic pre-Romanovian Russian history, qv in CHRON4. However, they appear to have missed a few naval charts. It seems as though military archives (and archives in general) must contain a considerable amount of interesting information.

4. The identity of Persia.

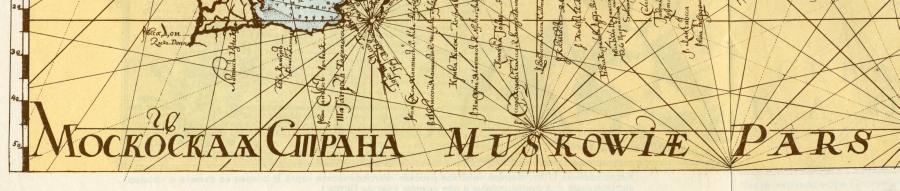

On the military map of Peter the Great dating from 1702 we see the legend “Moskowiae Pars” next to “Land of Moscovia”, qv in fig. 1.3. Therefore, “pars” must be a synonym of the word “land”, which resembles the word “Persia”, or PRS without vocalizations.

The implication is that the word “Persia” as used by many of the “ancient”, mediaeval and even late mediaeval cartographers, did not necessarily concur with the modern geographical localization of Persia. We see that the word could simply be used as a synonym of “land”, or “country”. Due to the emergence of a great many countries, or fragments of the former “Mongolian” Empire, in the epoch of the XVI-XVII century, many Persias appeared on the maps of the epoch. We have already seen that the name Persia was used for P-Russia (or B-Russia) = White Russia, France, Turkey and Iran, qv in CHRON1, CHRON2 and CHRON4.

By the way, the Azov Sea is referred to as “Meootiss” on a military map of 1702 – “Zee Paless Meootiss”, qv in fig. 1.1, which is the very name that the “ancient” historians had used. Thus, the “ancient” name of the Azov Sea was still used in the XVIII century, under Peter the Great.

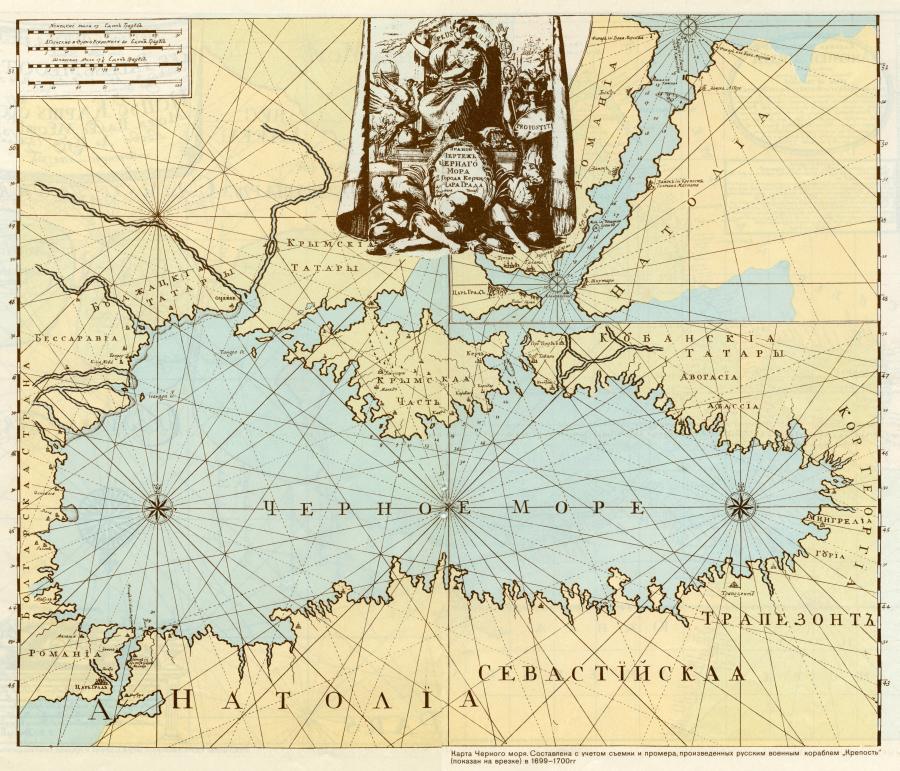

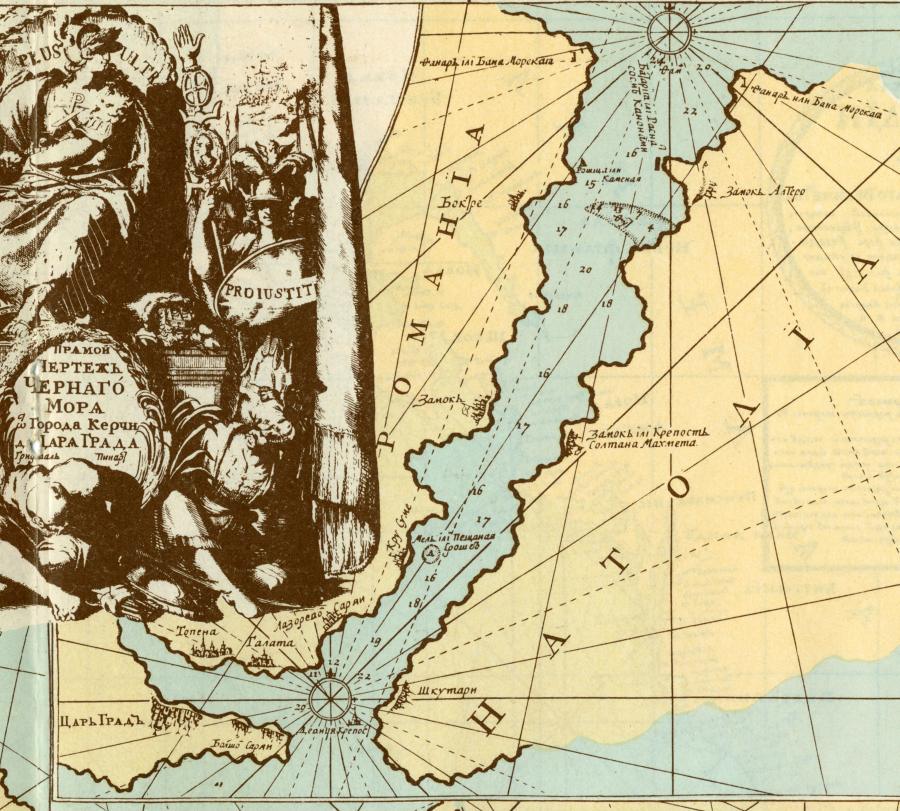

LeLet us turn to a Russian military map of the Black Sea that was compiled somewhat earlier, in 1699-1700 (see fig. 1.4). Upon it we see the name “Kuban Tartars” yet again (fig. 1.5). We see that the Kuban Cossacks were still referred to as “Tartars” around the end of the XVII century. We also see the Budjak Tartars next to Basarabia. The Crimean Tartars are naturally present as well. Turkey is referred to as Anatolia, whereas the former Byzantium is called Romania.

5. Czar-Grad and the multiple Saray cities on the maps dating from the epoch of Peter the Great.

It turns out that Constantinople as indicated in the Russian military maps of the XVIII century ([73]) was neither called Istanbul, nor even Constantinople, the way it should have been referred to in the XVII-XVIII century if we are to believe in the veracity of the Scaligerian chronology, but rather “Czar-Grad”, which is presumably its “ancient” name. In particular, this implies that the use of an “archaic” name in a given text does not imply the text itself to be “ancient”.

Fig. 1.6. Constantinople is called Czar-Grad in the Russian military naval chart of 1699-1700. Therefore, the allegedly “ancient” Russian name “Czar-Grad” was still used in Russia at the end of the XVII century. Taken from [73].

In the same military map of 1699-1700, we see another city next to Czar-Grad, possibly a suburb thereof – Greater Saray, qv in fig. 1.6. Therefore, the two names are in close proximity on the map, which is in full accordance with our reconstruction, qv in CHRON4. The name Saray is a vestige of the Russian Empire, or the Horde, which had once been united with Turkey, or the Ottoman Empire. The word Saray is derived from the word Sar (or Zar) – a likely synonym of the word “Czar”. Therefore, the names of the two cities really translate in the same way, hence their proximity on the map, qv in fig. 1.6.

To the north of Czar-Grad, on the other side of the Golden Horn strait, we find another Saray – the Azure Saray, qv in fig. 1.6. The city of Czar-Grad was virtually surrounded by various Sarays.

6. The dating of 750 as inscribed upon a Russian naval chart, proves that Empress Yelizaveta Petrovna reigned in the eighth century as counted from the Nativity of Christ, and not the XVIII.

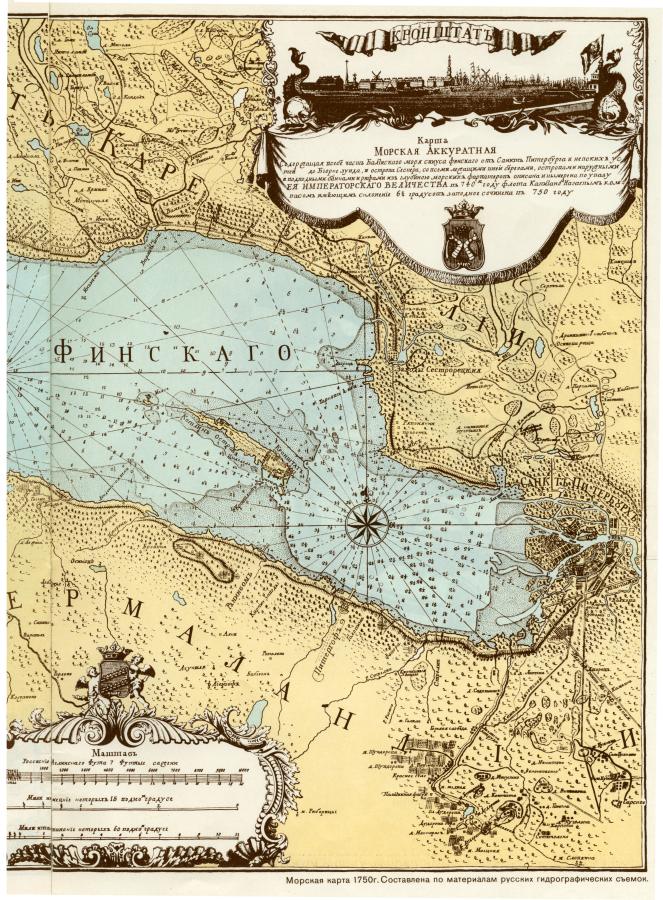

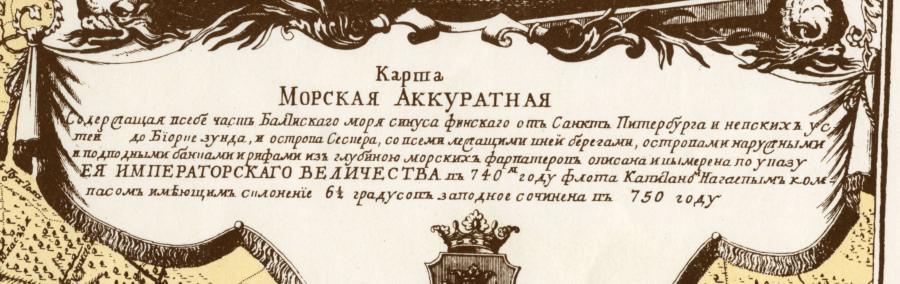

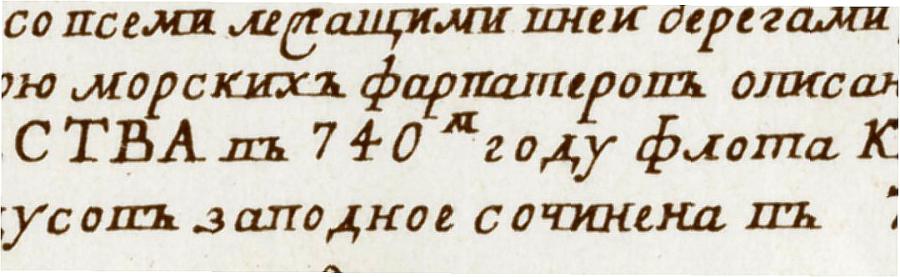

Let us now consider the Russian naval chart that was compiled in the XVIII century, the epoch of the Russian empress Yelizaveta, by Captain Nagayev (Nogay?), qv in fig. 1.7. Bear in mind that Yelizaveta Petrovna reigned between 1741 and 1762 – in the XVIII century, that is. Nevertheless, we can clearly see the writing on the map: “Kronstadt. Accurate naval chart . . . measurements and descriptions were made on the orders of Her Imperial Majesty in the year of 740 by Captain Nagayev of the Russian Navy . . . compiled in 750”, qv in fig. 1.8.

Therefore, we can see that even in the XVIII century some of the datings were still transcribed in the archaic manner, without the figure of one in the thousands place, writing 740 or 750 instead of 1740 and 1750. This implies the count of years from the XI century A. D. (Let us remind the readers that the XI century is the erroneous dating calculated by mediaeval chroniclers instead of the real one, or the XII century. Let us remind that the emperor Andronicus-Christ (1152-1185), also called Russian Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky, idem Apostle Andrew the First, was crucified in 1185 in Czar-Grad; see our book "The Czar of the Slavs", see English page of the site chronologia.org).

Fig. 1.7. “Naval chart of 1750. Compiled in accordance with the materials of the Russian hydrographic surveys” ([73]). Eastern part of the map. Taken from [73].

Fig. 1.8. Fragment of the Russian military naval chart of Captain Nagayev (Nogai?) compiled in 1750. Nevertheless, the date that we see on the map is transcribed as 750 – the millenarian figure of one is missing! This could theoretically suffice for dating it to the VIII century A. D. and no the XVIII, as suggested by the Scaligerian chronology. Taken from [73].

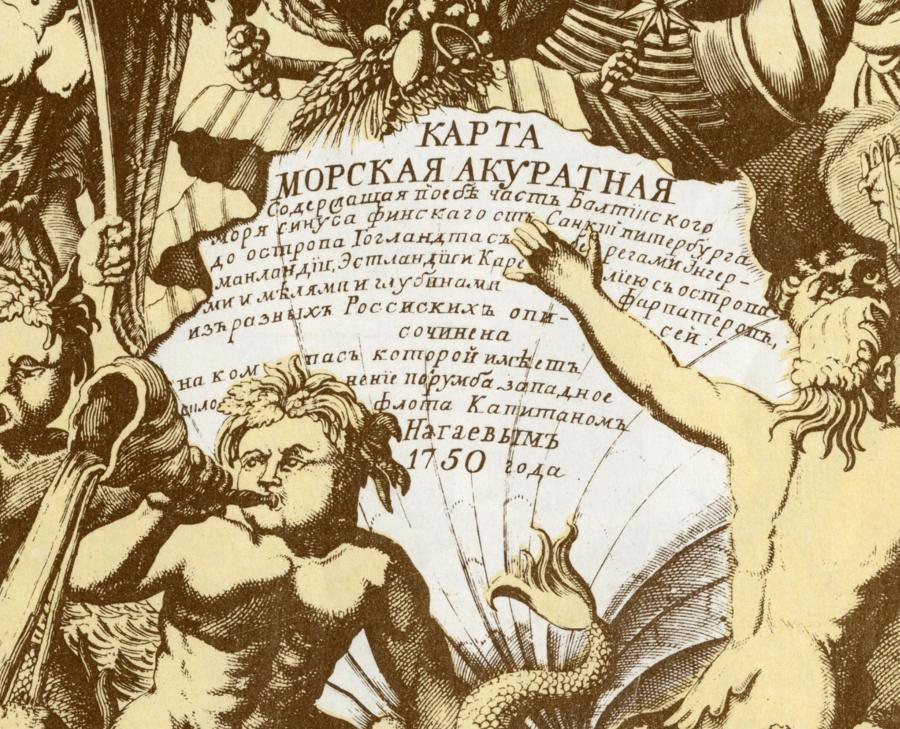

Fig. 1.9. Another military naval chart of Captain Nagayev (Nogai?). “Naval chart of 1750. Compiled after the results of the measurements carried out by the hydrographers from the school of Peter the Great primarily” ([73]). Taken from [73].

Fig. 1.10. The monogram from

the map of Captain Nagayev (Nogai?)

dating from 1750.

The date is already transcribed

in the modern format – as 1750.

Taken from [73].

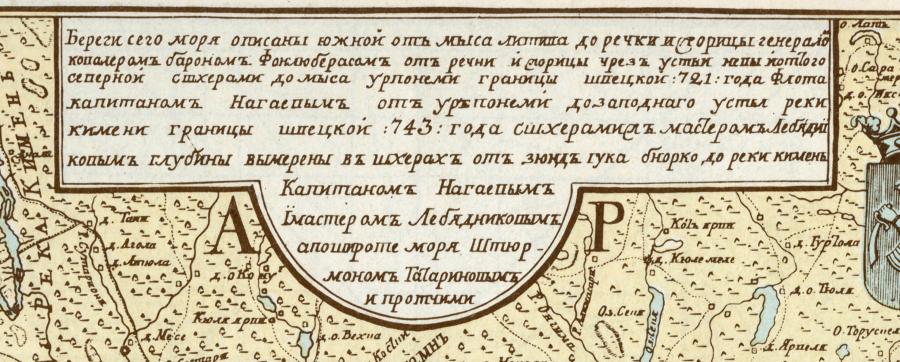

Fig. 1.11. Inscription on the map of Captain Nagayev dating from 1750.

The dates are still transcribed in the old fashion,

as 721 and 743 – without the figure of one in the thousands place.

Taken from [73].

This isn’t a random error, either – there are two dates in the description of the map, 740 (measurements and description) and 750 (actual compilation), qv in fig. 1.8. If we didn’t know that Yelizaveta lived in the XVIII century A. D., we could have easily dated this map to the alleged VIII century A. D. in Scaligerian chronology, which would make the dating a thousand years off the mark, which is the precise value of the Roman chronological shift, already known to us quite well. This is how phantom reflections of mediaeval documents appeared in deep antiquity.

Another naval chart of Captain Nagayev (Nogay?) dating from 1750 can be seen in fig. 1.9. The date in the top right corner is already transcribed in the modern fashion, as 1750, qv in fig. 1.10. However, in the top left corner we see the date and the name of the map’s actual compiler, which, amazingly enough, tells us that one part of the map was described by Nagayev in the year of 721, and the other – in 743, by the same character. Once again, there is no figure of one in the beginning of the date (fig. 1.11). Therefore, both dates were transcribed in the old fashion, sans “thousand”. The cartographers of captain Nagayev (Nogay) must have vaguely remembered the mediaeval tradition (which was a hundred years off the mark), according to which the Nativity of Jesus Christ had taken place 750 before their time, and not 1750; simultaneously, we see the very same date transcribed on the same map as 1750, which is the modern fashion.

Let us remind the reader that in CHRON1, Chapter 6:13, A. T. Fomenko formulated the hypothesis of how the chronological shifts came into being, including the millenarian one. The first figure of one, presumed to stand for a “thousand” today and introduced in this capacity as recently as in the XVIII century, had originally transcribed as the letter I or J, or the first name of the name Jesus (IESUS, or Jesus). Therefore, the symbol I in the transcription of the dates could have initially stood for the name of Jesus and not a figure. In other words, “I.740” stood for “the 740th year since Jesus”.

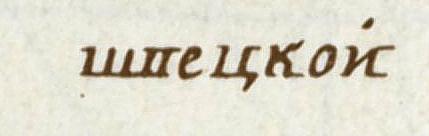

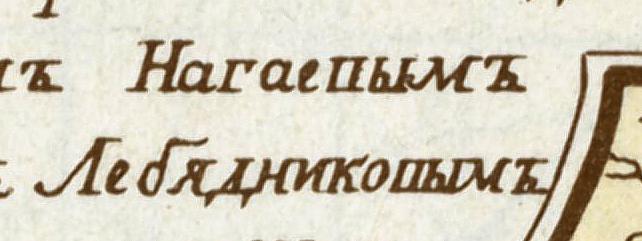

Fig. 1.12. The inscription on the map of Captain Nagayev transcribes the letters В “V” and П “P” in the same manner – the name ШПЕЦКОЙ (Shpetskoi) would be written as ШВЕЦКОЙ (Shvetskoi) nowadays. Thus, the transcription of certain Cyrillic letters wasn’t yet established in the XVIII century. Taken from [73].

Fig. 1.13. The inscription on the map of Captain Nagayev transcribes the letters В “V” and П “P” in the same manner – today we would write the names НАГАЕПЫМ (Nagayep) and ЛЕБЯДНИКОПЫМ (Lebyadnikop) as НАГАЕВЫМ and ЛЕБЯДНИКОВЫМ (Nagayev and Lebyadnikov, respectively). Taken from [73].

Fig. 1.14. The inscription on the map of Captain Nagayev transcribes the letters В “V” and П “P” in the same manner – the word ФАРПАТЕРОМ (Farpaterom, “navigating channel”) would be written as ФАРВАТЕРОМ (Farvaterom) nowadays.

Fig. 1.15. Map dating from 1701 that is considered to be the first one ever printed in Russia.

Most probably, earlier maps of the XIV-XVI century were destroyed. The Romanovs presented themselves as enlighteners, claiming to have brought culture to Russia and taking the credit for the birth of cartography, the formation of the fleet and the first timid steps of science. Taken from [73].

Fig. 1.16. The map of Peter the Great demonstratively portrays the conquered Nogai Cossacks = Tartars, who lived in the region of the Azov Sea. The Cossack bunchuks and the flags with the Ottoman crescents and stars are laid down at the feet of the Romanovs. Taken from [73].

By the way, curiously, instead of the letter B in the inscriptions of both maps of the captain Nagaev, a letter indistinguishable from P is used. Fig.1.12, Fig.1.13, Fig.1.14. In this regard, we will inform the reader that in the old Russian texts letters В, П, and К were written NEARLY SIMILAR. You should always keep in mind this circumstance when reading old names and titles. Furthermore, B and P are still often confused and replaced each other according to the well-known linguistics rule of resembling sounds.

By the way, it is rather curious that the map published in 1701 is “the first geographical map that was printed in Russia”. The measurements were performed under the supervision and with direct participation of Peter the Great, qv in fig. 1.15.

The southern coast of the Azov Sea’s Taganrog Bay, which is located at the estuary of the Don, is referred to as “The Land of Nagay”. The modern Crimea is called “Crimean Part”, qv in fig. 1.15. This is quite natural; however, the area that lies to the north of the Azov Sea, above Taganrog Bay, is called similarly – “Crimean Land”. This is very odd from the Millerian and Romanovian point of view.

One must pay attention to the subject of the artwork in the bottom right of the map, qv in fig. 1.16. The Cossacks, or the Tartars (apparently, Nogai in origin) lay down their Cossack bunchuk poles decorated with Ottoman crescents and stars. The gigantic Muscovite Tartary had still been very strong in the epoch of Peter the Great – the victory over “Pougachev” only took place in the XVIII century, qv in CHRON4. However, in order to raise the spirits of his allies, Peter the Great must have been very eager to emphasise the Romanovian control over a small part of the Nogai land adjacent to the Azov Sea.