Chapter 1.

DATING THE NATIVITY OF CHRIST AS THE MIDDLE OF THE XII CENTURY.

6. DATING OF THE GOSPEL EVENTS ACCORDING TO THE PALAEA.

(THE INDEPENDENT DIRECT DATING ACCORDING TO THE OLD SOURCE).

6.1. THE THREE GOSPEL INDICTION DATES IN THE OLD PALAEA.

Apparently it is also possible to find the direct dating of the Gospel events in the old texts. In this chapter we will talk about the Gospel dates contained in the old Russian Palaea from the Rumyantsev reserve of the Russian State Library. To remind you, Palaea is the old church book no longer in use, but up until the XVII century supplant of the Biblical Old Testament for Russian readers. Palaea also covered the events of the New Testament. This being said, whilst doing so it would sometimes supplement the Gospels. It should be pointed out that Palaea essentially differed from the traditional Old Testament canon. It was not just a version of the Bible as we know it, but a completely independent book. But it covered the same events as the contemporary canon Bible.

At first we will make the necessary explanations concerning the dates in the old sources following our book ‘Biblical Russia’ and CHRON6, ch.19. It is known that the old chronicles widely used the following method of writing down the dates, which eventually completely fell out of use.

The number of the year was determined not by one number, but by three, each of which changed within certain constraints. These numbers had their own names: ‘indiction’, ‘Solar Cycle’ and ‘Lunar Cycle’. Each of them increased annually by one, but as soon as it arrived at its designated limit it was reset back to one. And so on. This way instead of one essentially infinite calculator of years used today, the indiction method applied three finite cycle calculators. They predetermine a year with three small numbers each of which couldn’t exceed the close limits designated to it. They were:

- Indiction which varied from 1 to 15 and then was reset to 1;

- Solar Cycle which varied from 1 to 28 and then was reset to 1;

- Lunar Cycle which varied from 1 to 19 and then was reset to 1.

A chronicler who used the indiction calendar could write the following for example: ’the given event occurred in indiction 14, Solar Cycle 16, Lunar Cycle 19. The following year such and such events took place in indiction 1, Solar Cycle 18, Lunar Cycle 2’. And so on.

As those numbers-limiters 15, 28 and 19 included in the indiction calendar are relative primes, any of their combinations is repeated only in a number of years equal to the product of these numbers: 7980 = 15 x 28 x 19. Thus the recurrence of these indiction dates occurs only 7980 years later. It follows that within a time interval of almost eight thousand years long the indiction method determines the year precisely.

By the XVII century the old method of calculating years by using indictions, Solar Cycles and Lunar Cycles became irrelevant. However in the texts of the preceding epoch of the XIV-XVI cc. it was still widely used. The XVII century scribes didn’t understand the meaning of such dates and distorted them whilst copying. It is possible that in some cases the distortions were made intentionally with a view to destroying the old chronological tradition. Thus, for example, Solar Cycle was often omitted. Sometimes the words Solar Cycle or Lunar Cycle themselves were present in a manuscript, but the numbers expressing their value were lost. And so forth.

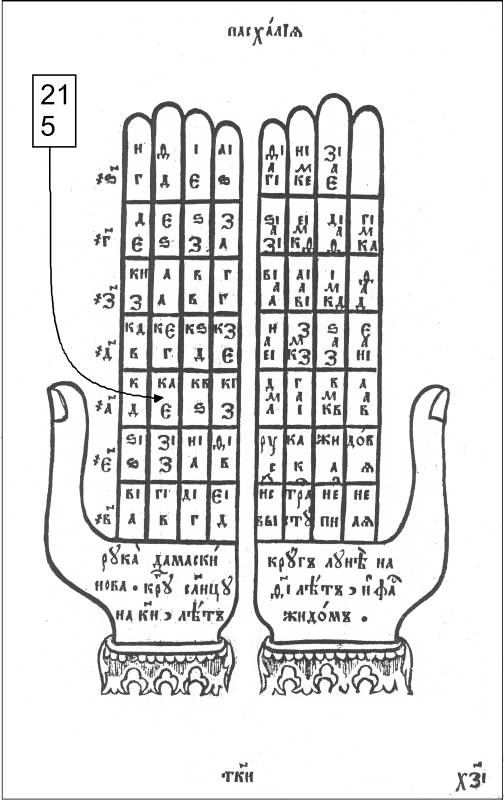

In the old texts the Solar Cycle occurring in the indiction date could have been given indirectly, but as a Dominical letter (a vrutseleto letter) of such and such finger on John of Damascus hand (Computus, Easter Calendar calculations – Translator’s note). The fact is that the values of Solar Cycles in the past were often situated on a special table-picture according to the fingers on the hand of John of Damascus. On it under each value of the Solar Cycle a vrutseleto corresponding to it was shown, fig.1.33  . Looking at fig.1.33 it is easy to verify that a finger and a vrutseleto fully define Solar Cycle. Therefore, let’s say, in the old chronicle instead of ‘Solar Cycle 11’ could have been ‘Solar Cycle 6 on the little finger’. Indeed, we look at fig.1.33

. Looking at fig.1.33 it is easy to verify that a finger and a vrutseleto fully define Solar Cycle. Therefore, let’s say, in the old chronicle instead of ‘Solar Cycle 11’ could have been ‘Solar Cycle 6 on the little finger’. Indeed, we look at fig.1.33  and see, that vrutseleto 6 on the little finger of John of Damascus hand does in fact define Solar Cycle 11. But the posterior scribe, who has already grown unaccustomed to the indiction dates and was used to era calendars, could have misunderstood such an entry, and, let’s say, omitted the words ‘little finger’. By this he was turning Solar Cycle from 11 into 6. Or for example he could have mixed up the name of a finger. Such substitutions shift the indiction date by HUNDREDS and even THOUSANDS years. Such mistakes in the indiction dates occurred often. There is a disadvantage in it for the global chronology. It is understandable, that over time they abandoned such a method of writing the dates down.

and see, that vrutseleto 6 on the little finger of John of Damascus hand does in fact define Solar Cycle 11. But the posterior scribe, who has already grown unaccustomed to the indiction dates and was used to era calendars, could have misunderstood such an entry, and, let’s say, omitted the words ‘little finger’. By this he was turning Solar Cycle from 11 into 6. Or for example he could have mixed up the name of a finger. Such substitutions shift the indiction date by HUNDREDS and even THOUSANDS years. Such mistakes in the indiction dates occurred often. There is a disadvantage in it for the global chronology. It is understandable, that over time they abandoned such a method of writing the dates down.

However, luckily, the accurate scribes in many cases still preserved for us either complete or partial indiction dates retrieved from the old texts. Let us refer to the old Russian hand written manuscript Palaea kept in the Rumyantsev reserve of the State Library, Moscow, call mark F.256.297. Three dates in connection with Christ are immediately defined in it. They are namely the indiction dates of the NATIVITY, BAPTISM and CRUCIFIXION.

To cite Palaea: ?

����������� �����: "� ���� 5500 ������ ������ ���������� ���� ������� ��� ��� ���� ������� ������� � 25 ����. ���� ������ ����� �� 13, ���� �� 10, ������� 15-��, � ���� ��������� � 7-�� ��� ���" (�����, ���� 275, ������). ��. ���.1.34 . "������� ������ ������� ������. � ���� 5515 �� ������� ������ ������� ������� ������� ��� �������, � ��������� � ���� 23 ����. ��� ��� ����� ���� ����� � ���������, 13 ������ ���� � �� ����� �����������. � 15 ���� ������� �� ������ �� ���������� ����, 30-�� ��� �������� ������ ������ ������� � 6-�� ���� � 7-�� ��� ��� ������� 15 ���� ������ 3 ����������� ������. � �� ���� ������� ����� ���� ������ 12, � ������ ���� �������, � �� �������� ����� �� ����� 3 ���� �� ������ ����� �������. ��� ��� ������� ����� � �������� ������� � ����������� ������� ������ ����� ������. ��� �� 18-� ���� ������[�] ��������� �������� ������� ��� ���� ������� �������� ���� �������� � ���� 5530 ����� � 30 ����, � ����� � 6-� ��� ���, ������� 3, ���� ������ 7, ���� 14, � ����� �����" (�����, ���� 256, ������, ���� 257). �� ���.1.35

. "������� ������ ������� ������. � ���� 5515 �� ������� ������ ������� ������� ������� ��� �������, � ��������� � ���� 23 ����. ��� ��� ����� ���� ����� � ���������, 13 ������ ���� � �� ����� �����������. � 15 ���� ������� �� ������ �� ���������� ����, 30-�� ��� �������� ������ ������ ������� � 6-�� ���� � 7-�� ��� ��� ������� 15 ���� ������ 3 ����������� ������. � �� ���� ������� ����� ���� ������ 12, � ������ ���� �������, � �� �������� ����� �� ����� 3 ���� �� ������ ����� �������. ��� ��� ������� ����� � �������� ������� � ����������� ������� ������ ����� ������. ��� �� 18-� ���� ������[�] ��������� �������� ������� ��� ���� ������� �������� ���� �������� � ���� 5530 ����� � 30 ����, � ����� � 6-� ��� ���, ������� 3, ���� ������ 7, ���� 14, � ����� �����" (�����, ���� 256, ������, ���� 257). �� ���.1.35 .

.

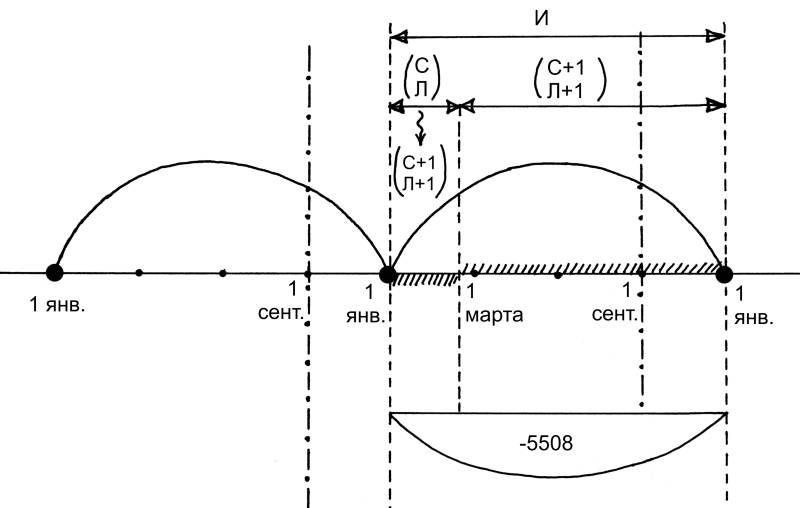

This passage from the ancient Palaea mentions a number of dates quintessentially different from each other. The two dates are the direct dates of the Byzantine era from Adam, i.e. year 5500 for the Nativity of Christ, year 5515 – for the beginning of Tiberius’ reign and year 5530 for Christ’s Crucifixion. All three dates recorded in this way were quite clear for both the late mediaeval chroniclers of the XVI-XVII cc. and the scientists of the modern era. They don’t require decoding and can be translated into the years of A.D. by simple subtraction of a digit, 5508 or 5509 (depending on the season). To clarify, for the months from January to August of the Julian calendar 5508 should be deducted, from September to December – 5509. Therefore it was very straightforward for the scribes and editors to correct such recording of the dates according to the latest trends in chronology. Moreover, as we understand it now, such dates were inserted by the scribes (or editors) particularly in the XVI-XVIII cc. But in the ancient sources themselves, which they were either copying or editing, the dates ‘from Adam’ as a rule were missing, instead of them there were archaic indiction dates.

Fortunately some scribes still tried to preserve the old initial indiction dates. Though they could not understand their meaning any longer and therefore unintentionally distorted them. For instance they mixed up Lunar Cycle and Moon’s age (which is far from being the same thing!). Or they might be mistaken about the fingers of the hand of John of Damascus when determining the Solar Cycle. Which we will encounter.

First of all we will comment on the direct scaligerian dates stated in Palaea. To say straight off, they DO NOT AGREE with the corresponding indiction dates stated there. Thus, for example, for Christmas date in 5500 from Adam are given indiction 15, Solar Cycle 13, Lunar Cycle 10. However in fact in 5500 from Adam the indiction was 10, Solar Cycle was 12 and Lunar Cycle was 9. Before us there is an entirely different set of the calendar data. Where you cannot remedy the situation by shifting around several years. We will also note that in 5508 from Adam i.e. in the standard beginning of A.D., the indiction was 3, Solar Cycle 20 and Lunar Cycle 17. Also an entirely different set of data.

We see the same thing with the direct scaligerian dating of Baptism on the 30th year after Christmas, i.e. circa 5530 from Adam, judging from the scaligerian date of Christmas as 5500 stated in Palaea. But in 5530 from Adam the indiction was 10 and Solar Cycle was 14. I.e. the indiction doesn’t match. And again it is impossible to correct the situation by shifting the dates by several years. When aligning the indiction the Solar Cycle will be ‘lost’ and vice versa.

The very same situation is with the direct scaligerian dating of the Crucifixion. In Palaea year 5530 from Adam is stated. But here, most likely, the number G=3 is being lost, as earlier it is clearly stated, that the Crucifixion took place 33 years after birth. For Nativity the scaligerian dating of 5500 from Adam is given. But the indiction doesn’t match for either 5530, nor for 5533. In Palaea for the crucifixion the indiction 3 and Solar Cycle 7 are stated. But, as we already said earlier, in 5530 the indiction was 10 and Solar Cycle 14. Meaning that in 5533 the indiction was 13 and Solar Cycle was 17. Once again – entirely different numbers.

CONCLUSION. The direct scaligerian dating for the Nativity, Baptism and crucifixion were, most likely, stated in Palaea by the later editors and were taken from the ‘scaligerian history textbook’ so to say. The indiction dates are the remainders of the archaic manuscript and arrived here from the old primary source. It could be, that the editors kept them as by then they could not understand them very well and luckily considered them not to be harmful. So they kept them!

Thus, the cited text of Palaeacontains the three indiction dates. One of them is complete, the other two are not. Let us list them.

THE FIRST DATE states Nativity: Solar Cycle 13, Lunar 10, indiction 15.

THE SECOND DATE determines Baptism: indiction 15, Solar Cycle 3 on the ring finger. Lunar Cycle is not stated.

THE THIRD DATE states crucifixion and resurrection: indiction 3, Solar Cycle 7, Lunar 14 = Jewish Passover.

To clarify, in the latter case most likely ‘Lunar 14’ means not Lunar Cycle, but the 14 days age of the Moon’s age, i.e. full moon. Which, incidentally, is clarified by the words: ‘and Passover Judaic’. To remind you, that the Judaic Passover according to the Christian Church sources took place on the ‘14th Lunar’, i.e. using modern terms, on the astronomical full moon.

To note, the scribe does not feel any longer the difference between the expressions ‘Lunar 14’ in the third date (here it is the age) and ‘Luna 10’ in the first date (here it is Lunar Cycle). Though in the original text the phrasing of it was presumably more precise. It is clear that for the scribe, even if he had special knowledge, these dates were not comprehensible any longer. And here we were very lucky as the scribe-chronologist or editor was notable to ‘correct’ the incomprehensible dating. Being naïve in thinking that if he didn’t understand them, then it is not possible to understand them at all. But time goes by and what was not possible in the XVII-XVIII cc. is becoming accessible now.

Proceeding to the decoding of the three dates from Palaea: nativity, baptism and crucifixion. It would seem that the easiest way to decode them would be to take them exactly as they are written. But if you take them literally they give you a nonsensical answer. And even a self-contradictory one.

Let us take the first date, for example: ‘Solar Cycle 13, Lunar Cycle 10, indiction 15’. Before us is the full indiction date, which therefore has one solution in the interval from year 1 ‘from Adam’ to years 7980. I.e. from 5508 B.C. to 2472 A.D. Here 7980 = 15 x 19 x 28 is a product of relatively prime intervals of three indiction cycles– indiction, Solar Cycle and Lunar Cycle, see above. The result is as following: the literal meaning of the first date gives us 1245 from Adam, i.e. 4265 B.C. (As it is a December date, here we deduct 5509). The ‘date’ of the Nativity of Christ we arrived at is evidently nonsensical. The middle of the fifth millennium B.C. – too early even for the scaligerian version of chronology. Besides, such a date does not correspond with the other two indiction dates stated in the same text. For example, for the second date which contains many solutions (as it is incomplete) the ‘solution’ closest to year 1245 from Adam is this: year 1470 from Adam – considering the fact, that Baptism has to be AFTER Nativity. But then the age of Christ at the time of Baptism would have been more than 400 years old, which is clearly nonsensical.

CONCLUSION. We see before us the already somewhat tainted indiction dates.

Nevertheless, the scribes were, we should think, accurate enough and the detriment was hardly intended. The errors which occur unintentionally, as a rule appear in complex and ambiguous places. For example – close and confusing spelling of some letters, inability of a scribe to comprehend a certain specific term, etc. That is why, having altogether three dates CONCERNING A SHORT INTERVAL OF TIME we hope to correct the slipped in errors and to restore the original old dates. Let us ask ourselves a question: is there a way, while acknowledging minimal errors of a scribe, to read all the three stated dates in such a way, so that they occur close in time to each other and to the above mentioned independent astronomical dating of the Star of Bethlehem? Will the date of Nativity fall in the interval between 1120 and 1160? And the dates of Baptism and crucifixion approximately 30-40 years later corresponding with the age of Christ according to the Gospels. We would like to highlight that we lay down rather strict conditions. To fulfil these requirements by chance for all three indiction dates even with the consideration of the likely errors of the scribes is almost impossible. The reader can easily be certain of it from the following analysis.

6.2. THE PROBLEM OF DECODING THE OLD INDICTION DATES.

6.2.1. ACCIDENTAL AND ’SYSTEMATIC’ ERRORS INTRODUCED INTO THE OLD DATES BY THE SCRIBES.

The above described situation with the indiction dates taken from the old text is typical. In many cases when translated into the dates A.C. they give nonsensical results out of sync with each other. Hence a problem of decoding such dates arises. First of all it is necessary to understand which errors exactly could have crept into such dates. One kind of such errors is the accidental ones. For example, a scribe could have mixed up the alike letters-numbers, let’s say, alpha and delta, which confused one-figure with four-figure. This is one of the typical errors in the Greek and Slavic manuscripts. Usually they occurred accidentally, simply due to carelessness. However a good scribe made such mistakes rarely, and when there are a lot of dates, then it is unlikely that such mistakes would creep into all of the dates or the majority of them.

Another matter is an error related to not understanding some already forgotten factors. Such an error ‘systematically’ effects instantly all or nearly all dates. A thorough analysis which we conducted showed, that in fact such ‘systematic’ errors could have occurred in the indiction dates. Primarily due to the following two reasons.

REASON ONE – INITIAL INCONGRUITY OF THE POINTS OF THE THREE CYCLES CHANGING THROUGHOUT THE YEAR. Which subsequently was forgotten all about, though the clear traces of the initial incongruity survived.

REASON TWO – THE OLD METHOD OF COUNTING SOLAR CYCLES BY VRUTSELETO ON THE FINGERS OF THE HAND OF DAMASCENUS. When applying this method Solar Cycle was represented not by a number from 1 to 28, but by a number from 1 to 7 (which is called ‘vrutseleto’) indicating which finger exactly is the given number on: indicatory, middle, ring finger or little finger. At that, Solar Cycles denoted by the same number on the different finger digits were considered to be of close value. They could have been mixed up. In other words, the designation of a finger in a date was not very stable and sometimes was even omitted, especially if a date was abbreviated. Similar to the way we often omit the number when we drop higher digits when indicating a year.

Let us describe the situation in detail. Beginning with the first reason: incongruity of the cycles’ starting points. Let us address the history of the origin of the indiction cycle (indiction) and the two paschalian cycles (Solar Cycle and Lunar Cycle).

6.2.2. CONSIDERING A POSSIBLE SHIFT IN THE BEGINNING OF INDICTION IN RELATION TO THE SOLAR AND LUNAR CYCLES.

It is known that the beginning of the Byzantine indiction is the 1st September. I.e. it is specifically on the 1st September that the indiction number changed. See, for example, the work by Bolotov V.V. where the given question is discussed in detail [20], v.1, p.102-103. This is how the 1st September is determined in the Orthodox Menologion according to the Old style: ’the beginning of indiction, videlicet that is, of a new year’. It is thought that the SEPTEMBER beginning to the year is of Byzantine origin. I.e that it originated in New Rome, at the Bosporus. It is thought that the beginning of an indiction year was determined as September by Constantine the Great allegedly in the IV c. A.D. [72], p.88. In fact, as we know it now, this refers to the end of the XIV century A.D. (a shift by approximately 1050 years), when Dmitry Donskoi = Constantine the Great established the beginning of the yeaR as SEPTEMBER. Most likely in honour of his victory at the Battle of Kulikovo on the 8th SEPTEMBER 1380. We will give the details further on. It is thought that the Emperor Constantine allocated the beginning of the year to a different date than the 1st September, but that subsequently it was changed to the 1st September for convenience [72], p.88. We will repeat that the Battle of Kulikovo took place on the 8th September, on the day of Mother of God’s (Theotocos’) Birthday. The September ‘indictions are usually called the indictions of Constantine the Great’ [20], v.1, p.103.

It is thought that earlier, before Constantine the Great, the Roman year began on the 1st JANUARY [72], p.207. Allegedly as such the beginning of the year was established in Rome in year 45 B.C.

But alongside September, the ‘Bosporus’ (Greek) beginning of the new year, in the old times there also existed JUNE – the Egyptian beginning of the new year, arranged to coincide with the beginning of the harvest. As it happens ‘in Egypt the agricultural works were completed much earlier and usually by the 12 of the month of nouni (equivalent of our 6th June)… the rising of the Nile waters begins’ [20], v.1, p.104. Thus the archaic Egyptian year began in the middle of summer and coincided with summer solstice in the middle of June. But not with the autumn equinox in September as a Byzantine year does. Our research of the Egyptian zodiacs showed that, in fact, the most ancient Egyptian zodiacs, as for example Athribian Zodiacs (discovered by Flinders Petrie) indicate to the archaic beginning of a year in June [MET3]:4, section 7.1.9. The most recent Egyptian zodiacs however count a year from September, i.e. Byzantine, Greek style. Thus the Egyptian indiction began with June [20], v.1, p.103. It was also called ‘Nile indiction’ [20] v.1, p.104.

It is considered that the Roman indiction was the beginning of a ‘financial year; in the Roman Empire [72], p.82; [20], v.1, p.108. Unlike Solar and Lunar Cycles, indictions were not connected with the paschal Computus [20], v.1, p.108.

We shall draw your attention to the fact that the beginning of a year was always linked to either one of the equinoctial points or solstice points. Winter solstice is close to the 1st January, vernal equinox - close to the 1st March, summer solstice is close to the 1st June and finally autumnal equinox is close to the 1st September. Unfortunately there is no information surviving about the beginning of the indictions in March. However a year began in March, therefore the March indiction cannot be excluded, strictly speaking.

As we do not really know what indiction was meant by the author of the ancient source from which the indiction dates found their way into Palaea, we have to consider all four possibilities. Namely the beginning of indiction in the following moments: 1st January, 1st March, 1st June and 1st September.

Now onto the Solar and Lunar Cycles. In contrast with indiction they are the calendar-astronomical cycles closely related to the computation of paschal cycle (computus). Therefore their beginning was actually different. If we refer to the Orthodox Computus we can derive from it that the beginning of the cycles we referred to was in March. Thus for example the XIX century ‘Instruction to Pashcalia’ directly informs us: ‘In the church computation hitherto March remains first; as from its 1st day there originates the Solar and Lunar Cycles used in Paschalia, and also Vrutseleto and Vysokos (leap year – Translator’s note)’ [120], p.12.

To clarify, the Sun circles or Solar Cycle are closely connected to the so called vrutseletos or vrutseleto letters using which the days of the weeks were computed for a particular calendar date. Let’s say for the 1st March of a given year. And the skipping of the vrutseleto letters always happens between February and March because February contains an additional day during the leap years. That is why a rule of transition of vrutseletos is different for the normal years and leap years. Therefore in the very determination of paschalian vrutseletos and Solar Cycles a March year is implied [72], p.69. We will note that in the Western catholic churches, where the calendar calculations were connected to the beginning of the year in January, vrutseleto were not used and instead another method was used, based on so called ‘Sunday letters’ [72], p.92-93.

Nevertheless technically a possibility of the old Palaea meaning some other more archaic beginning of Solar and Moon Cycles should not be excluded. For instance in the old ‘Explanatory Palaea’ we find a statement telling us that Lunar Cycle begins in January. In other old sources this beginning could have been in June close the Summer solstice. As a matter of fact we know from the history of astronomy that the 19 years Lunar Cycle was invented by the ‘ancient’ Greek astronomer Meton allegedly in 432 B.C [113], p.461. The historians of astronomy inform us: ‘The Calippic cycles carry on the tradition started by Meton who discovered and introduced into Athens the 19 year Lunisolar Cycle… THE DATE OF SOLSTICE WAS RECOGNISED AS THE BEGINNING OF THE FIRST CYCLE (ACCORDING TO THE GREEK SOURCES) – 23 June year -431… in the Athenian calendar this date corresponded to by 13 of the month of Skirophorion [113], p.461.

Here the special interest for us is in the information from the old sources, that METON DEFINED THE DATE OF THE SUMMER SOLSTICE AS THE BEGINNING OF THE FIRST CYCLE. The exact date given above (27th June 432 B.C. or in the other denominations: year -431) is a result of the calculations and interpretations of the scaligerian chronologists based on the erroneous chronology of Scaliger and Petavius.

We would point out that the scaligerian dating of the Meton’s activity causes some kind of unresolved problem in the history of astronomy. Its analysis led us to the independent dating of the epoch of the invention of the Metonic cycle circa X century A.D. See the details in ‘Bibleiskaya Rus’’ (‘The Biblical Russia’) and CHRON6, ch.19:4:5.

There existed various opinions regarding the ‘natural origin’ of the paschal cycles. Thus, for example, Matthew Blastares thought that the ‘naturally-occurring’ beginning of Solar Cycle is the 1st October. He even came up with some kind of scholastic explanation for it. Specifically that ‘no 1st day of any month apart from October coincides with the first day of the first solar period (i.e. – Solar Cycle – Author) [6], p.363. Apparently, the beginning of the paschal Solar Cycle was for some reason being shifted from March to January [6], p.363. Where no reasonable argument was given, besides one: it is possible to safely do so (without serious consequences) as ‘January and February put together comprise two Lunar months’ [6], p.363.

We will highlight that moving the beginning of Solar and Lunar Cycles to any given date was of no great practical consequence in the paschal calculations as they applied only to March and April. No equinox points or solstice points fall into the narrow gap between April and March, therefore it is of no importance which of these points the computation of the paschal cycles is connected with. That is why over time they began to forget about the old associations between the beginning of the paschal cycles and any certain dates.

This yields the following conclusion. Most likely it was March that acted as a starting point for Solar and Lunar Cycles. Strictly speaking, however, we should not exclude the other three possibilities: June, September and January. It is important that the starting point of indiction, generally speaking, could have differed from the starting point of the paschal cycles. And it is necessary to consider this when decoding indiction dates. Otherwise we will end up with errors BY HUNDREDS OR EVEN THOUSANDS OF YEARS. Let us give you an example.

Let’s say for example that indiction changed in September and Solar and Lunar Cycles in June. Then in the same September year indiction will be constant and Solar Cycle and Lunar Cycle will change their values. Before June and after June they will be different! But, if we change Solar Cycle and Lunar Cycle in the indiction date by one while keeping indiction the same, then the DATE WILL CHANGE DRAMATICALLY. Let us say, indiction in some September year was 12, Solar Cycle in the beginning of the year was 20 and Lunar Cycle in the beginning of the year equalled 5. In nine months, in June indiction will remain the same (it will change only in September), i.e. will equal 12. Solar Cycle and Lunar Cycle will change and will become equal to 21 and 6 accordingly.

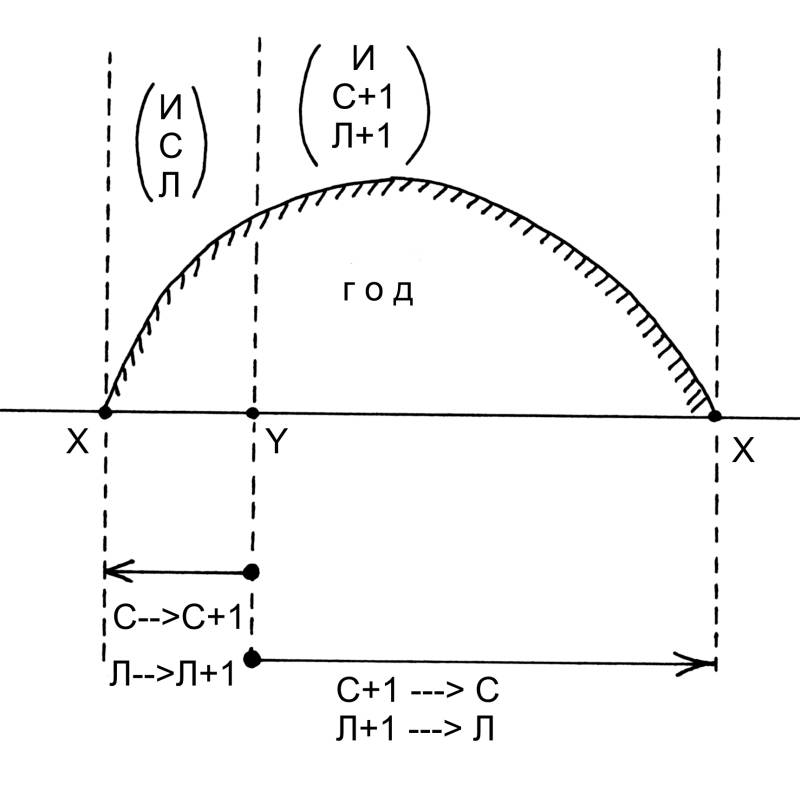

Next we assume that the ancient chronicler wrote two dates in the given September year into his chronicle, see fig.1.36  . Let’s say a September and a July date. For the first date he wrote down the following: indiction 12, Solar Cycle 20, Lunar Cycle 6. For the second date: indiction 12, Solar Cycle 21, Lunar Cycle 6.

. Let’s say a September and a July date. For the first date he wrote down the following: indiction 12, Solar Cycle 20, Lunar Cycle 6. For the second date: indiction 12, Solar Cycle 21, Lunar Cycle 6.

Today when recalculating the specified dates for the ‘era from Adam’ without considering the difference in the moment of the skip we will get the following ‘result’. The first date: year 1392 from Adam, the second date: year 2457 from Adam. We can see that the difference between them amounts to more than a thousand years, see fig.1.36  . Though initially the both dates were situated within the same September year. We can clearly see what enormous mistakes such ‘forgetfulness’ of the chroniclers could lead to. Naturally the example we show here is purely conditional and is used only to show the magnitude of the arising errors.

. Though initially the both dates were situated within the same September year. We can clearly see what enormous mistakes such ‘forgetfulness’ of the chroniclers could lead to. Naturally the example we show here is purely conditional and is used only to show the magnitude of the arising errors.

Therefor it is necessary to be very careful when recalculating the old indiction dates into the modern calendar keeping in mind that there well may be a ‘hidden danger’ lying there, which we have referred to here. Further we will describe in detail what exactly needs to be done.

6.2.3. CONSIDERING A POTENTIAL UNCERTAINTY IN INDICATING A FINGER ON THE DAMASCENUS HAND.

In regards to the second error named above, it is easier to take into account, though it leads to a greater amount of variants. As we said earlier Solar Cycle could have been determined by the fingers of the Damascenus hand, seefig.1.33 . For example, instead of Solar Cycle 21 they could write: ’5 on the middle finger’ sometimes it was called ‘the great digit’ as it is the longest. In fact looking at fig.1.33

. For example, instead of Solar Cycle 21 they could write: ’5 on the middle finger’ sometimes it was called ‘the great digit’ as it is the longest. In fact looking at fig.1.33  we can see that ‘the fifth vrutseleto on the middle finger’ corresponds to ‘Solar Cycle 21’, see fig. 1.37

we can see that ‘the fifth vrutseleto on the middle finger’ corresponds to ‘Solar Cycle 21’, see fig. 1.37  .

.

But the ancient chronicler, the eyewitness of the events, generally speaking could not have pointed out a ‘finger’ for the date contemporary to him and could only cite number 5. That was quite sufficient for his contemporaries as it was not at all difficult to unequivocally re-establish the ‘finger’ knowing the epoch of the events. Even today we say ‘year ninety eight’ instead of a full phrase: ’one thousand nine hundred and ninety eight’. But over time the epoch of an event fades from memory. The chroniclers which follow, separated from the eyewitness-chronicler by many tens of years, and by then lacking the precise information about an approximate epoch of the events described, for some personal reasons were compelled to replace the missing ‘finger’, which naturally could have caused errors. That is why when decoding the indiction dates, strictly speaking, it is vital alongside Solar Cycle cited in the source, to consider the other three values which have similar number with it on the other fingers. Altogether there are four ‘significant fingers’ on the Damascenus hand, see fig.1.33  .

.

Even if the finger is directly pointed at in the date, it is still necessary to also look at the other fingers, as this ‘finger’ could have been added by a more recent scribe. In any case it must be noted that when it comes to the calendar or Paschal calculations Solar Cycles with the same number (i.e. vrutseleto) on the different fingers were considered ‘close’ to some extent. See for example [120], p.17.

The error in regards to a finger could have been caused not just by the carelessness of the scribes, but also by the following. Today on the Damascenus hand, Solar Cycles increase from left to right, from index finger towards the little finger, see fig.1.33  . That makes sense. Both in our time and in the XVII century, when the Augmented Psalter was being printed, from which we adopted the ‘Damascenus hand’, they were already writing from left to right for some time. But in the old times, most likely, they were writing from right to left, as the Arabs still do. If Solar Cycle by the fingers on the Damascenus hand was entered into a chronicle when they wrote from right to left, then clearly the order of the fingers in ascending order of Solar Cycles will be reverse. That is why in the place where the more recent chronicler would enter let’s say ‘middle finger’, the earlier author would indicate the ring finger. As the box to the same Solar Cycle would be on one finger when writing from left to right, and on a different finger when writing from right to left. In place of the little finger there would be the index finger. Instead of the middle finger – the ring finger. And so on.

. That makes sense. Both in our time and in the XVII century, when the Augmented Psalter was being printed, from which we adopted the ‘Damascenus hand’, they were already writing from left to right for some time. But in the old times, most likely, they were writing from right to left, as the Arabs still do. If Solar Cycle by the fingers on the Damascenus hand was entered into a chronicle when they wrote from right to left, then clearly the order of the fingers in ascending order of Solar Cycles will be reverse. That is why in the place where the more recent chronicler would enter let’s say ‘middle finger’, the earlier author would indicate the ring finger. As the box to the same Solar Cycle would be on one finger when writing from left to right, and on a different finger when writing from right to left. In place of the little finger there would be the index finger. Instead of the middle finger – the ring finger. And so on.

As we will see, it this exact systematic mistake which appears in the indiction dating of Palaea. In actual fact it is not even the error of the source. The scribe accurately copied what was in front of him. But the look of the table itself could have changed into dissymmetrical. Which is important to consider when decoding the indiction dates.

6.3. RECALCULATING THE OLD INDICTION DATES FOR THE MODERN CALENDAR ALLOWING FOR A POSSIBLE INCONGRUENCE OF THE POINTS OF THE CYCLE PHASES, IMPLIED IN THE GIVEN DATE.

As explained before when re-calculating an old indiction date into September year according to the era from Adam it is necessary to consider that in the old primary source indiction ’jumps’ into a certain point X, when at the same time Solar Cycle and Lunar Cycle ‘jump’ into a generally speaking, different point Y. But conversion of the indiction dates into the years according to the era from Adam was usually made by both the later and the contemporary chronologists without consideration of the given circumstance according to the following rule. Indiction is a remainder of dividing the value of September Byzantine year from Adam by 15, Solar Cycle is a remainder of dividing it by 28, and Lunar Cycle – from dividing by 19. But here it is silently assumed that Solar Cycle and Lunar Cycle always ‘jump’ over 1 September, the same way as indiction does. But this would not correspond with the source which stipulates that the ‘jumps’ occur during the different points of the year. As a result, we can calculate the year of an event given in the document completely wrongly.

To avoid this error we need to know points X and Y. If we know them we can adapt the source data into a contemporary format suitable for use in the modern conversion tables. I.e. specifically we should either decrease by one the values of Solar Cycle and Lunar Cycle after point Y, which corresponds to shifting their ‘jump’ to the beginning of the following indiction year. Or, alternatively, we should increase them by one in the range between X and Y, which corresponds to shifting their ‘jump’ point to the beginning of the current indiction year. Naturally the two specified methods lead to different results. Only one of them can be correct. If we do not know what to do exactly, it is necessary to consider both variants, see fig.1.38  .

.

If, for example, the source implies January indiction, but March Solar and Lunar Cycles. Let’s say we need to move their entries three months back aligning them with the previous January. As we shall see this is exactly what needs to be done for the Palaea studied by us. We should act as follows.

For the months – January and February – we should increase Solar Cycle and Lunar Cycle from the source considering them already ‘having jumped over’ on 1 January. While in the primary source it was assumed that they would jump over only on 1 March. Thus we somehow artificially reset the view point of an ancient author by transferring it to our contemporary one. After this we can use the modern conversion tables of indiction dates into the dating according to the era from Adam, and then according to A.D.

The described method of conversion of indiction date with the shifted beginnings of the cycles is shown in fig.1.39  . Specifically we should look at two cases.

. Specifically we should look at two cases.

- For the dates from the 1 January to the 28-29 February we should increase Solar Cycle and Lunar Cycle, given in the primary source, by one. Then – calculate the Byzantine, September year from Adam by remainders in division. And finally deduct the number 5508. We will arrive at the number of the January year of A.D. Naturally the negative values would correspond with the years B.C. (according to the astronomical count, i.e. including the zero year).

b) For the dates from the 1 March to the 31 December Solar and Lunar cycles do not have to be corrected. But when converting into the years A.D., 5508 should be always deducted the same way as in the previous case. The matter is that using this method we will make an error for the months from September to December by decreasing the result by one in the interim calculation of September year from Adam. This will be compensated by us still deducting 5508 for the stated months, and not 5509 as ought to be done when converting from the Byzantine September era from Adam into the years of A.D. for the period between September to December.

6.4. DECODING OF THE THREE GOSPEL DATES FROM THE OLD PALAEA.

Let us begin with decoding the indiction date of Nativity as it is a full date and there will be the least amount of the possible solutions. It is said in Palaea: indiction 15, Solar Cycle 13, Lunar Cycle 10. As we already have seen, if understanding this entry literally, we arrive at a nonsensical result. Therefore most likely we face here either one or both of the above mentioned ‘systematic’ errors. We shall assume here and further on that the scribes did not allow for any accidental slips of the pen. Otherwise we would not be able to find any solution satisfactory to the strict conditions we have placed. To remind you, the three unknown desired dates from Palaea should be situated at a definite distance from each other, i.e. approximately 30 years from Nativity to Baptism and 30-40 years from Nativity to Crucifixion.

Considering that originally in the date of Nativity the finger on the Damascenus hand was not specified and that it was ‘re-established’, alas incorrectly, we have four variants for Solar Cycle. Solar Cycle 13 stated in Palaea corresponds to number 2 on the middle finger, see fig.1.33  . The following Solar Cycles also correspond to the same vrutseleto 2 on the other fingers: on the index finger – 24, on the ring finger – 2, on the little finger – 19. All the variants should be checked. We conducted three calculations for each variant: unadjusted in Solar and Lunar cycles, then adjusted by +1 and finally with adjustment by -1. In this way we considered all the possibilities arising from the listed potential errors.

. The following Solar Cycles also correspond to the same vrutseleto 2 on the other fingers: on the index finger – 24, on the ring finger – 2, on the little finger – 19. All the variants should be checked. We conducted three calculations for each variant: unadjusted in Solar and Lunar cycles, then adjusted by +1 and finally with adjustment by -1. In this way we considered all the possibilities arising from the listed potential errors.

We wrote a computer program enabling us to carry out the above mentioned calculations, see Appendix 3.

As a result we arrived at the following answer, see Table 1.

Table 1.

There are only three dates in the table we resulted with, which in theory can be interpreted. Specifically: year 87 A.D., year 867 A.D. and year 1152 A.D. The rest of them – either deep antiquity, long before A.D. ,or the XX century. Among the three dates which make sense one PERFECTLY corresponds with the independent date of Nativity of Christ in the middle of the XII century, which we arrived at. It is year 1152 A.D.

We should stress that the probability of a chance of one of the three dates scattered along the one-and-a-half thousand year interval falling into a proximity of year 1150 is very small. However the result we arrived at is nearly exact! 1152 corresponds well with all the independent dating of Nativity of Christ we have found earlier.

But let us see now what the other two dates according to Palaea will give us – for Baptism and crucifixion. They may or may not confirm the dating of Nativity as 1152. For example if there were some accidental errors which slipped into the given indiction dating of Palaea. And if the primary source stated some other date. One thing is clear, that it is impossible for all the three dates to fall into one and the same epoch. Moreover – into the middle of the XII century, which we anticipated and presented before.

Let us list all the possible variants of decoding Nativity and Baptism dates as two tables (Table 2 and Table 3). We will mark with an asterisk the Solar Cycle directly specified in Palaea. If a finger in Palaea is specified directly we will also mark with an asterisk a ‘duel-value’ finger (where a mirror symmetry of a table is possible, as discussed earlier). Three more values of the Solar Cycle included in the table differ from the value which is determined directly by the change of the finger, i.e. has the same vrutseleto with it.

In the case of Christ’s Baptism, the Solar Cycle in Palaea is given as ‘3 annular’. It corresponds with the 3rd vrutseleto on the ring finger. I.e. to understand the text of Palaea literally, the Solar Cycle will be 14, see fig.1.33 . However taking into account a possible error in the finger we should also consider the other three possibilities: Solar Cycle 8 (3 on the index finger), Solar Cycle 25 (3 on the middle finger) and Solar Cycle 3 (3 on the little finger).

. However taking into account a possible error in the finger we should also consider the other three possibilities: Solar Cycle 8 (3 on the index finger), Solar Cycle 25 (3 on the middle finger) and Solar Cycle 3 (3 on the little finger).

Table 2.

As the date of crucifixion Palaea gives: indiction 3, and Solar Cycle 7. This Solar Cycle corresponds to 1 on the little finger. Therefore we should also consider the following variants: Solar Cycle 12 (1 on the index finger), Solar Cycle 1 (1 on the middle finger) and Solar Cycle 18 (1 on the ring finger (annular)).

Table 3.

Lunar Cycle is not given either for Baptism, or for crucifixion, therefore there are significantly more solutions for them than for Nativity. So what can we see from the tables presented?

There are only two possible ways to decode three dates given in Palaea accurate to the Gospel description. Both solutions, i.e. both sets of three, exactly correspond with the direct account in Palaea that from Nativity to Baptism there passed 30 years, and from Baptism to crucifixion – 3 years. We are talking of the following possibilities.

The first variant: 87 A.D., 117 A.D., 120 A.D.

The second variant: 1152 A.D., 1182 A.D., 1185 A.D.

THERE ARE NO OTHER SOLUTIONS. Where the second solution PERFECTLY corresponds with the rest of the independent dates we arrived

at above. In particular with the astronomical dating of the Star of Bethlehem in the middle of the XII century.

Now we can get the final answer to the question posed above.

CONCLUSION.

a) All three indiction Gospel dates in the old Palaea (Rumyantsevsky Fund of the State library, manuscript f.256, 297) allows the only decoding corresponding to the Gospels and matching the other independent dating received above. The decoding of all the three dates in Palaea are accurate in the sense that they do not stipulate for any errors made by the scribes due to their negligence. The scribe-chronologist however was unable to avoid only two ‘consistent’ errors stated above which, as accurate as he was, are taken into account.

- The solution is as follows:

December 1152 for Nativity,

January 1182 for Baptism,

March 1185 for crucifixion.

COMMENT 1. In regards to the days of the week stated in Palaea and the exact calendar dates for Nativity and crucifixion, they were most likely calculated, based on the specific direct Scaliger dates. It was easy to carry out the count according to paschalia or using the vrutseleto letters. Thus for example, in year 5533 from Adam, Friday would fall on the 30 March. To remind you, Christ, according to the Gospels, was crucified on a Friday. The Scaligerian editors simply found a date, when in the last dates of March there was a Friday. It was then written into Palaea.

COMMENT 2. We can see, that in two or may be even in all three cases (if we do not take into account a possibility of a mirror reflection of the table) – for Nativity, Baptism and crucifixion – the indiction date, which survived from the edition of Palaea to present times, incorrectly states a finger on the Damascenus hand. As it was said earlier, this error could have appeared either accidentally due to the fact that at first a finger wasn’t stated at all and was added by the more recent scribes. Or systematically due to the fact that initially the Solar Cycles on the Damascenus hand were written from right to left, and later they began to write from left to right. Thus we are faced at best by two or at worst by three errors in the three tests. The question is – what is the likelihood of the ‘worst’ outside possibility? I.e. that in all three cases a finger turned out to be incorrect due to an accidental error? In other words, that all three times it was stated incorrectly entirely by chance?

A simple calculation shows, that with an incidental recovery of the missing finger on the Damascenus hand the probability of an error been made all three times out of three is great enough. It amounts to approximately 1/2. In fact the probability to make a mistake once equals 3/4, as altogether there are four fingers being used on the Damascenus hand (index, middle, ring and little). Therefore the probability of choosing the correct finger by chance equals 1/4. However, the probability of error is 3/4. Consequently, the probability of making an error independently all three times equals 27/64, i.e. approximately 1/2. In other words, fifty chances out of a hundred, that having three indiction dates, we will see an

error in a finger in all three of them. This is exactly what we see in this case.

We would like to make a general comment here. Today as a rule we are facing the texts which have undergone the Scaligerian editing of the XVII-XVIII cc. That is why if we wish to extract the true dates of the old events from them, we should draw upon those dates, which the Scaligerian editors were not able to understand and ‘correct’. Present attempts to ‘calculate’ the dates based on the simple concepts accessible for the XVII-XVIII cc. editors, will most likely give the result of their cunning calculations, with the aid of which history was being distorted.

The archaic indiction dates present a valuable material, as their decoding generally speaking is connected with some complex calculations inaccessible to the XVII-XVIII cc. editors. But today we may well carry out such calculations.

6.5. CONSIDERATION OF CHRIST’S NATIVITY DATE ACCORDING TO PALAEA.

Let us elaborate upon on the chronological details described in the given Palaea of the Gospel events. It directly says that Christ was crucified in the 33rd year of his life. It is also supported by the dates decoded above. However we should be aware of the fact, that the date of Nativity is secondary in regards to the dates of crucifixion and resurrection, as it was calculated based on the beliefs at the time of Christ’s life. THE DATE OF CHRIST’S CRUCIFIXION IS PRIMARY.

The matter is, that the ancient Christian writers and, most likely, even the Evangelists themselves, did not have the one and only point of view in regards to the length of Christ’s life. We cite: ‘There is no stable historical legend surviving about the time of Christ’s public ministry. The common view is that his ministry (i.e. from Baptism to crucifixion – Author) continued for three and a half years and his life ended in the 34th year, is based on the authority of Eusebius. There no full acknowledgement of this legend in the Gospel texts to be found… In the most ancient (pre-Eusebian) time there was another persistent view that Christ’s ministry lasted one single summer (Lords’ summer) (Hippolytus of Rome and the others): in this case Christ died at 31 years old, and based on the year of crucifixion the year of his birth should be calculated… The usual viewpoint of 33 and a half years of the mortal life of Christ does not have any sufficient grounds and Irenaeus already admitted to at least a 40-years old age of Christ; the same is apparently suggested in the Gospel of John’ [20], v.1, p.91-92. Here V.V.Bolotov means Irenaeus of Lyons and believes that he draws upon the information from John the Apostle himself, whom he was rather close to in time. In any case Irenaeus testimonial is considered to be very important [20], v.1, p.91.

All this being said, it follows that dating the crucifixion to the year 1185 is a more precise chronological statement, than dating Nativity to the year 1152. There were a lot of disputes about Christ’s lifespan, that is why the date of nativity ‘blurs into a splodge’, that can be calculated based on the date of crucifixion. Therefore we should not entirely trust the date of Nativity given in some or other source. It may always be amended by several years. That is why the date of Nativity in Palaea as year 1152 does not entirely contradict the date of year 1150 which we arrived at from the dating of the Jubilees, see above.

Here is the last note. As mentioned above, we do not know precisely which points of the indiction jump, and of the Solar and Lunar Cycles, were used in Palaea and the sources, from which the stated calendar data was borrowed. That is why we analysed all the possible variants in our calculations. But this does not mean that we cannot say precisely with which beginning of the year – January, September, March or some other, the year 1152 was calculated as the year of Nativity. For example, if it is a September year (which is very likely) then the traditionally accepted year 1152 A.D. with the year beginning in January would be the first year AFTER Nativity, beginning 6 days later. In other words, in this case the date of the Nativity of Christ would fall into September year 1152, but would fall out of January year 1152, where it would be necessary to attribute it to the previous year 1151. Therefore if we follow our contemporary calendar with the beginning of the year on the 1st January, then the exact date of Christ’s Nativity according to Palaea would have strictly speaking two variants: either the 25th December 1151 A.D. or the 25th December 1152 A.D.