Chapter 2.

IMPERATOR ANDRONICUS KOMNIN OF THE XII CENTURY - IT IS JESUS CHRIST DURING HIS PRESENCE IN TSAR-GRAD OF THE XII CENTURY.

16. THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM OR THE COMET HALLEY AND THE COMET ‘REPRESENTING ANDRONICUS’.

Nicetas Choniates mentions a certain comet appearing in the sky before Andronicus’ enthronement and ‘clearly representing Andronicus himself’. We quote: ‘At this time a comet appeared in the sky which indicated future troubles and CLEARLY REPRESENTED ANDRONICUS HIMSELF. In its appearance reminiscent of the coils of a snake the emergent superstar was now stretching and then after a while coiled and sometimes looked as if it had open jaws which horrified the fearful spectators’ [140], p.265. Choniates certainly does not connect a comet here with the birth of Andronicus, but clearly speaks of it ‘representing Andronicus himself’. On the whole Choniates quite often confuses the sequence of events and even mentions the same event in different variations. We have already spoken of that and we will come across it more than once in the future. So it is quite possible that here the subject of the matter is the comet heralding the birth of Andronicus. We see a very good correspondence with the Star of Bethlehem circa 1150 or (and) with the Halley Comet, which could have also appeared circa 1150, see above.

17. THE AGE OF CHRIST AND THE AGE OF ANDRONICUS.

According to the Gospels at the moment of his crucifixion Christ was between 30 to 50 years old, see the points raised above. We will remind you that the age between 40 and 50 years old appears to be referred to in the Gospel of John and mentioned by some of the old church writers. Today it is widely agreed that the age of Christ was between 30-33 years. Let us see now what Nicetas Choniates says about the age of Andronicus. On one hand Choniates calls him ‘an old man’ on a number of occasions, but at the same time claims that Andronicus looked rather youthful. We quote: ‘While having superb physique, he had enviable looks. ‘He was straight in stature, majestically tall, his face even until his old age was young-looking’ [140], p.358-359.

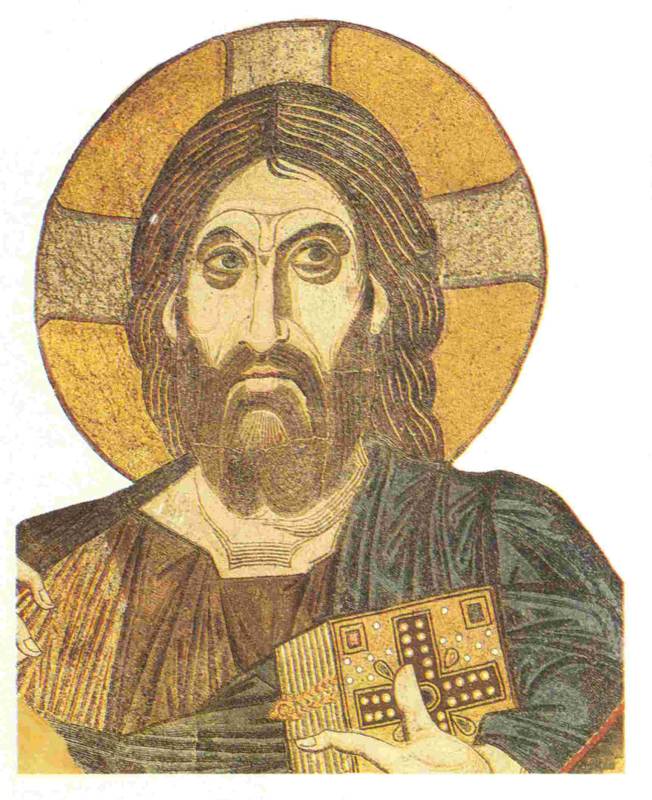

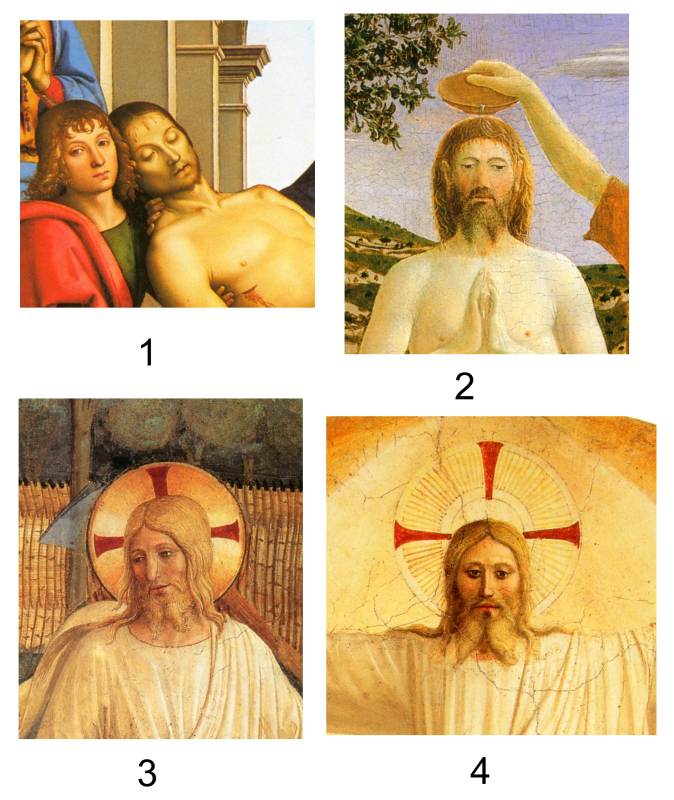

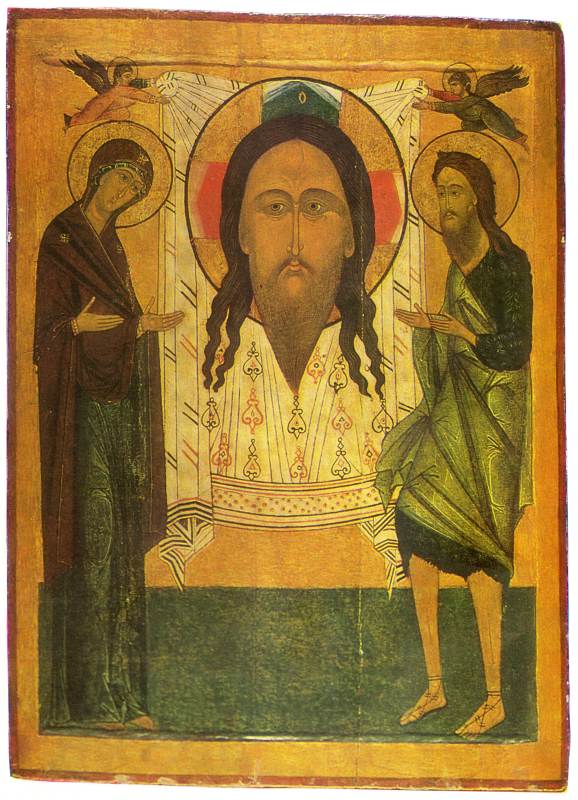

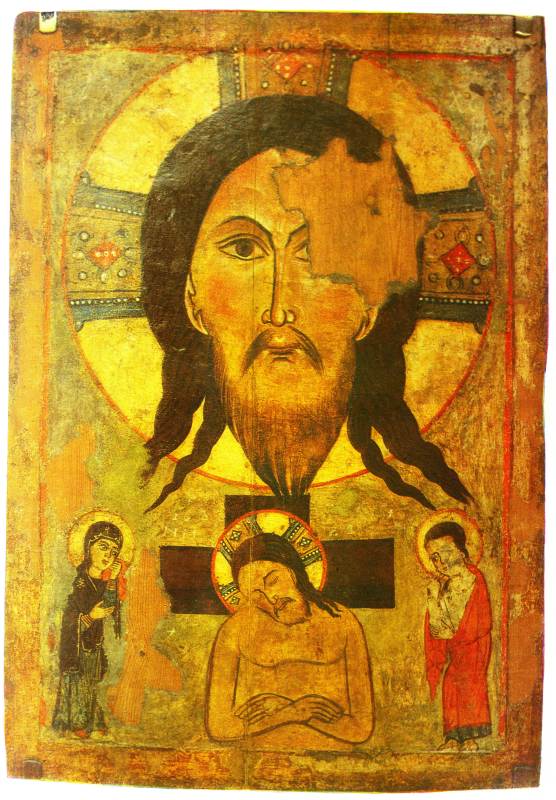

As a rule in the icons Christ is depicted as not old. However there are exceptions, though rare. There exist depictions of Christ where he is presented not entirely young, see for example fig.2.25  . Another example – the well-known mosaic in Saint Sophia’s Cathedral in Kiev.

. Another example – the well-known mosaic in Saint Sophia’s Cathedral in Kiev.

Evidently there were disagreements in the Christian tradition about the age of Christ before the crucifixion. The same kind of uncertainty shows through in the text of Nicetas Choniates, see above. He says that Andronicus was old, but at the same time looked rather youthful.

Nicetas Choniaates claims that Andronicus was already grey. For example Andronicus was called ‘silver haired’ [140], p.353. But grey hair can also appear at the age of thirty. Particularly if a person had a difficult life and suffered persecution. Certainly, in the icons Christ is usually depicted not grey. But there are exceptions to this rule as well. Besides it is possible that in the icons Christ is depicted at a younger age.

As a result we see that there are no significant contradictions between the age of Christ according to the Gospels and the description given by Nicetas Choniates. In both instances we see traces of uncertainty regarding the relatively exact age. It seems the only thing that it is possible to claim with certainty is that Christ as well as Andronicus was neither very young, nor very old. I.e. was in middle age. Probably between 30-45 years of age.

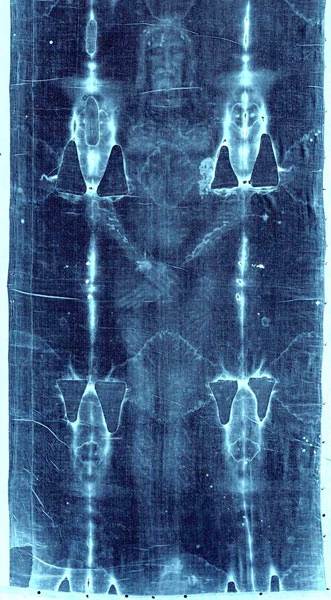

Let us look at the Shroud. On it there is also depicted a man in his middle age. ‘On the Shroud there is depicted a man with a beard. Long hair bundled as if from a tousled plait. His weight is approximately 79 kg, proportional physique, muscular’ [47], p.13.

Thus the image on the Shroud also shows that Christ was in his middle age. Neither a youth, nor an old man.

18. CHRIST’S FORKED BEARD AND ANDRONICUS’ FORKED BEARD.

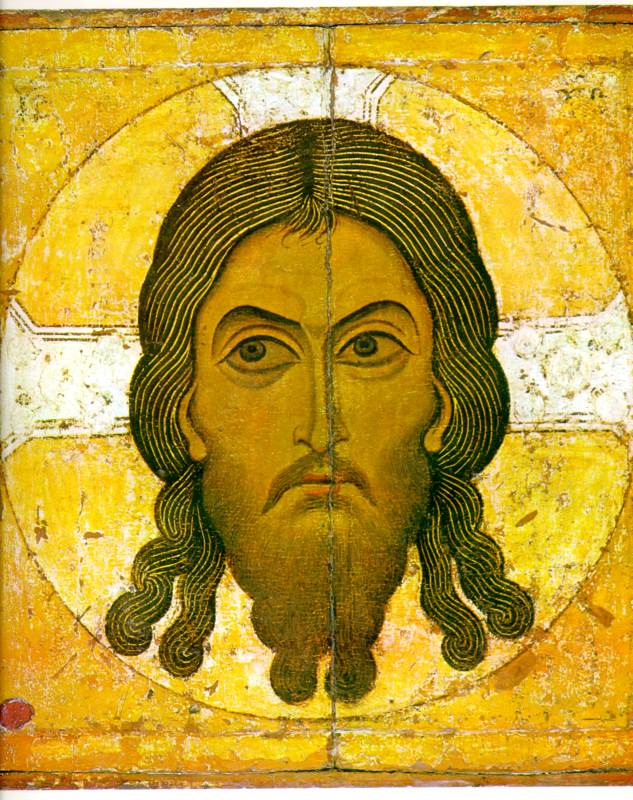

On many icons Christ is depicted with a forked beard. See for example the Russian icons in fig.1.24  and fig.2.26

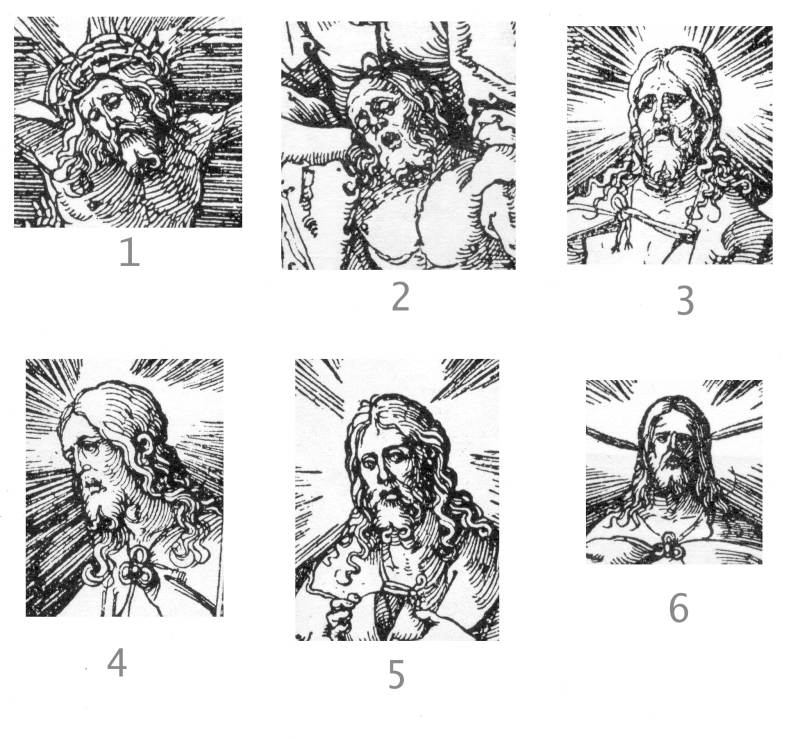

and fig.2.26  . In the engravings of ‘The Small Passions’ series which today are attributed to Albrecht Durer (Germanic school), Christ’s beard is mostly also depicted as forked, see the examples in fig.2.27

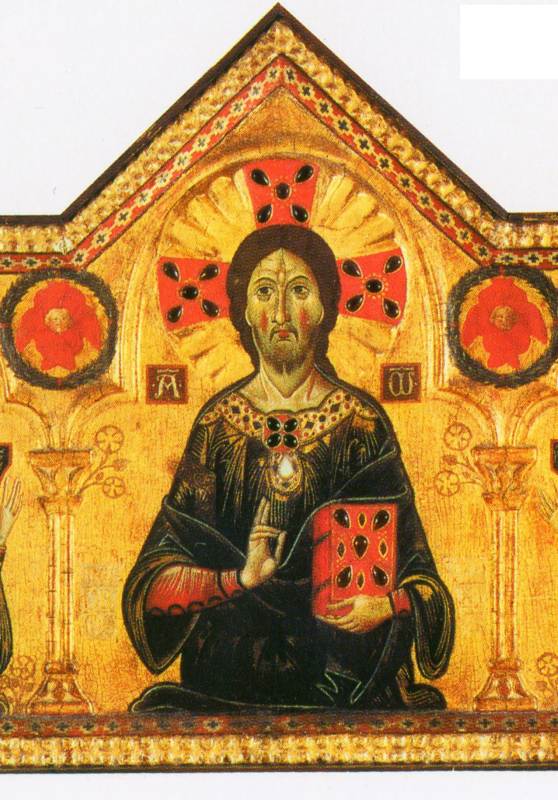

. In the engravings of ‘The Small Passions’ series which today are attributed to Albrecht Durer (Germanic school), Christ’s beard is mostly also depicted as forked, see the examples in fig.2.27  . Further see the images of Christ of the Italian, Florentine school in fig.2.28

. Further see the images of Christ of the Italian, Florentine school in fig.2.28  . Further see for example the paintings by: Pietro Perugino, Piero della Francesca, Fra Angelico – see fig.2.29

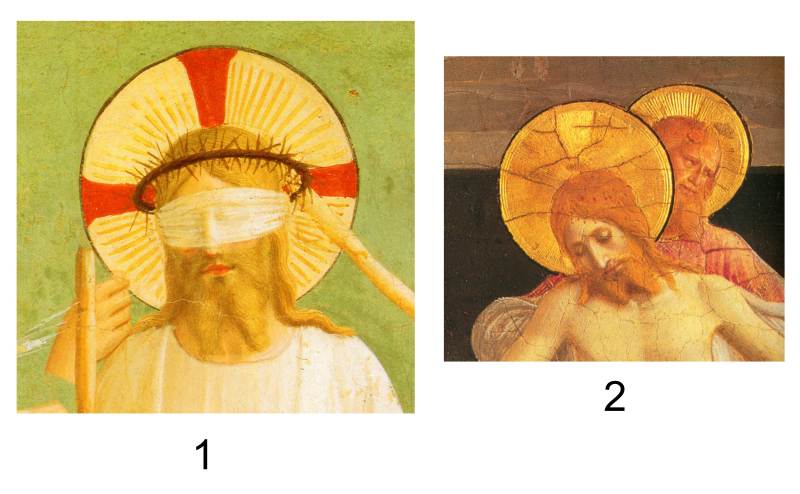

. Further see for example the paintings by: Pietro Perugino, Piero della Francesca, Fra Angelico – see fig.2.29  ; Fra Angelico – wee fig.2.30

; Fra Angelico – wee fig.2.30  ; Hieronymus Bosch – see fig.2.31

; Hieronymus Bosch – see fig.2.31  ; Michelangelo, Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano, Florentine School, Pinturicchio and assistants – see fig.2.32

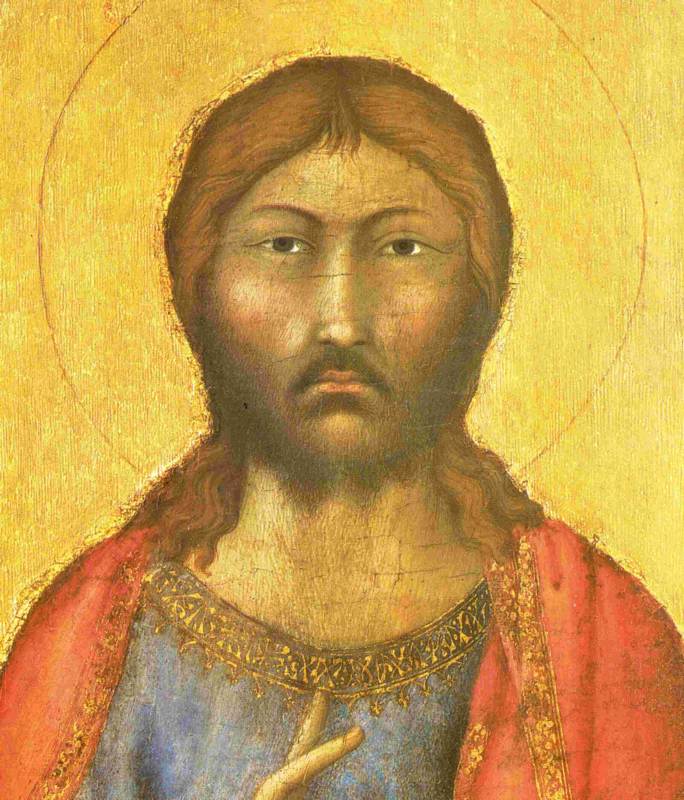

; Michelangelo, Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano, Florentine School, Pinturicchio and assistants – see fig.2.32  ; Simone Martini – see fig.2.33

; Simone Martini – see fig.2.33  ; Fernando Gallego – see fig.2.34

; Fernando Gallego – see fig.2.34  ; Bartolomeo Carducci – see his painting further; Carlo Crivelli [10], p.60, fig.50. There are quite a few similar early pictures surviving. Notably judging by various icons and the Shroud Christ’s beard was quite full.

; Bartolomeo Carducci – see his painting further; Carlo Crivelli [10], p.60, fig.50. There are quite a few similar early pictures surviving. Notably judging by various icons and the Shroud Christ’s beard was quite full.

Incidentally on the Shroud the beard looks forked though the image in that place is not clear enough to state it with certainty, see fig.1.15  and 1.17. However the researchers noted that on the Shroud there can be seen ‘a short beard PARTED IN THE MIDDLE’. See an article ‘Obraz tkani’ (The Image on the cloth’) on the website www.shroud.orthodoxy.ru devoted entirely to the Shroud of Turin.

and 1.17. However the researchers noted that on the Shroud there can be seen ‘a short beard PARTED IN THE MIDDLE’. See an article ‘Obraz tkani’ (The Image on the cloth’) on the website www.shroud.orthodoxy.ru devoted entirely to the Shroud of Turin.

The Mediaeval source ‘The Letter of Lentulus’ also claims that ‘He (Christ – Author) has a thick brown beard matching the colour of His hair, not long, but PARTED IN TWO’ [62], p.453.

And now let us refer to the Byzantine history. It turns out that Andronicus had a FORKED BEARD. Nicetas Choniates reports: ‘He has a long POINTED beard PARTED IN TWO’ [140], p.353. We will note that in some icons Christ’s beard is clearly parted in two, see above, but in some other ones it is clearly pointed, see fig.1.25  and fig. 1.26

and fig. 1.26  .

.

It has to be said that information on beard shape is not recorded for every Byzantine emperor. In regards to a forked beard, we could not find any other such mention in Byzantine history besides Andronicus. Such a beard style is quite a prominent trait. Overall the shape of a beard, particularly a forked one, is an unusual characteristic in the description of a ruler. Their appearance is quite often described in the chronicles, but the shape of a beard – rarely. That is why the coincidence is hardly accidental.

19. CHRIST’S FASTING AND ANDRONICUS’ FASTING.

The Gospels tell us in detail about Christ’s fasting: ‘Then Jesus was led by the Spirit into the wilderness … And after fasting forty days and forty nights, he was hungry’ (Matthew 4:1-2). And further: ‘where for forty days he was tempted by the devil. He ate nothing during those days, and at the end of them he was hungry’ (Luke 4:2).

Nicetas Choniates writes the following about Andronicus: ’He was a remarkably healthy person as he refrained from the dainties, was neither a glutton, nor a drunkard… If sometimes he happened to burden his stomach, he eliminated this temporary upset by working and fasting all day long, so that only in the end of the day he refreshed himself with a piece of bread and a cup of diluted wine’ [140], p.359.

When describing the other Byzantine emperors Nicetas Choniates says nothing of their fasting and temperance in eating. On the contrary, he reports of the magnificent royal feasts of the other rulers. Such a characteristic of Andronicus is very unusual. It perfectly corresponds with the Gospels.

It is interesting that in the Muslim fasting custom it is forbidden to eat only during the day, but it is permitted to eat after sunset. The traces of this custom are present in the Christian fasting. It is the so called sochelniki (Christmas Eve), when you eat only in the evening, ‘after the star’. It is possible that such a custom goes back to the fasting of Andronicus-Christ.

20. DRIVING THE TRADERS FROM THE TEMPLE.

Everyone knows the Gospel story of Christ driving the traders from the temple following his triumphant entrance to Jerusalem. ‘And Jesus went into the temple of God, and cast out all them that sold and bought in the temple, and overthrew the tables of the moneychangers, and the seats of them that sold doves. And said unto them, It is written, My house shall be called the house of prayer; but ye have made it a den of thieves’ (Matthew 21:12-13). And further: ‘And Jesus went into the temple, and began to cast out them that sold and bought in the temple, and overthrew the tables of the moneychangers, and the seats of them that sold doves. And would not suffer that any man should carry any vessel through the temple’ (Mark 11:15-16). See also (Luke 19:45-46) and ‘Strasti Khristovy’ (‘Passion of Christ’) quoted above.

Essentially the Gospels tell us that having entered Jerusalem Christ began to establish the new rules there. In particular, selling ‘doves’ and the money-changing stalls in the temples. It is not quite clear though what does it have to do with the doves? Why is it that Christ forbade selling them specifically? Could it be that they did not sell anything else in the temples? But apparently the ‘doves’ offended Christ the most of all. It looks like that by ‘doves’ the Gospels meant something different from the birds. For example selling of the church and public positions in general. Or it could be the selling of the indulgences, which many people always strongly objected to.

[127], p. 79. Here instead of the word ‘thing’ it is more clearly written a ‘vessel’. That is why it is quite possible that it refers to banning selling wine in the temples. What is clear is the fact that it was very profitable, and they did not want to give it up. It is for a reason the book ‘Strasti Khristovy’ (‘Passion of Christ’) directly states that the casting out of the temple became the main reason for the high priests plotting against Christ, see above.

In the biography of Andronicus the theme of ‘the casting out the traders’ is resoundingly clear. We have already spoken about Andronicus ceasing selling the public office or giving them out for bribery: ‘He did not sell the public positions and did not give them to just anyone for some donation, but would grant them for free and to those chosen ones. That is why … the people driven to death by the social troubles, as if having heard the trumpet of an archangel, were awoken from a long and heavy sleep and resurrected. And as they say… the bones began to join other bones, body parts with other body parts, so that in a short time a rather large number of the cities revived and became wealthy as before… He … stopped the oppression of the tax collectors and continuous extortions which were invented and turned into an annual tax by the greedy bureaucrats, who gorged on people as if they were bread, and turned it into a fixed amount’ [140], p.334.

By the way, let us draw our attention to the language of Choniates’ narrative at this point itself. There is a feeling that in the description of Andronicus he is constantly drawn to quoting the Book of Psalms, the Biblical prophecies or the associations with the Gospels. For example when talking about the revival of trading under Andronicus, Choniates uses a purely evangelical term ‘resurrection from the dead’. Let us compare with Matthew’s words for instance: ‘And, behold, the veil of the temple was rent in twain from the top to the bottom; and the earth did quake, and the rocks rent; And the graves were opened; and many bodies of the saints which slept arose, And came out of the graves after his resurrection, and went into the holy city, and appeared unto many’ (Mathew 27:51-53). Or for example the thirteen’s Davidic psalm: ‘ Lest mine enemy say, I have prevailed against him; and those that trouble me rejoice when I am moved’ (Book of Psalms 13:4) "Неужели не вразумятся все, делающие беззаконие, съедающие народ мой,как едят хлеб" (Псалтирь 13:4).And so on. Though here it seems there is no obvious reason for such Biblical associations. As it is referring to simply stopping bribery, and not to the Last Judgement.

It seems that ‘Choniates’ in his ‘Historia’ was working on a certain old text which was much closer to the Gospels and to the Bible on the whole. It is possible that ‘Choniates’ was striving to turn it into some topical social narrative. Nevertheless in some places the language of the old original peeps through.

According to Nicetas Choniates Andronicus restrained bribery so much, that the officials were afraid to not only accept bribes, but even simple quite harmless gifts: ‘Many distanced themselves even from the voluntary donations, avoiding them … like some kind of disease, lethal to anything coming in contact with it’ [140], p.333.

Further Choniates reports that ‘when sending the governors to the districts Andronicus allocated a generous fee for them and at the same time declared what punishment would be inflicted on them if they violated his orders’ [140], p.333-334. Andronicus never forgave any appointed governor who disobeyed his order to refuse bribes. Even in those cases where they were noblemen or even his own relatives. This inspired a torrent of rage against the emperor. Choniates calls him a ‘beast’ mercilessly persecuting the ‘good people’ for the smallest of wrongdoings. He writes: ‘Andronicus’ arrival was accompanied for many with distress and sorrow or even the loss of life or some other extreme misfortune. Having planted cruelty … in the heart of his soul … this man considered a day ruined if he did not seize or blind some nobleman … Like a merciless teacher who now and then would raise a whip to the pupils… Many could not find any peace even in their sleep … but having just fallen asleep would wake up in fear after seeing Andronicus in their dreams or those, who this fierce, headstrong and unforgivingly angry man sacrificed for his cruelty. What would happen in the last days according to the prophecy of the Son of God, i.e. that the two would be on one bed and one will be taken and the other will be left, the same sort of thing was happening in those days, as one of the spouses was suddenly seized and taken to torture… A father neglected his children, the children did not care for their father. If there were five people in one household, then the three turned against the two and the two against the three’ [140], p.332.

In other words, Andronicus entirely disregarded any family ties when handling legal matters. Here once again in Choniates’ text we can hear clear associations with the Gospels. In fact, Matthew thus conveys Jesus’ words: ‘Think not that I am come to send peace on earth: I came not to send peace, but a sword. For I am come to set a man at variance against his father, and the daughter against her mother, and the daughter in law against her mother in law. And a man's foes shall be they of his own household. He that loveth father or mother more than me is not worthy of me: and he that loveth son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me’ (Matthew 10:34-37). (Матфей 10:35-37).

And further the Gospels say: ‘…so shall also the coming of the Son of man be… Then shall two be in the field; the one shall be taken, and the other left. Two women shall be grinding at the mill: the one shall be taken, and the other left. Watch therefore: for ye know not what hour your Lord doth come’ (Matthew 24:40-42).

Here Nicetas Choniates openly and directly quotes the Gospels calling Christ the Son of God, see above.

Nicetas Choniates bluntly accuses Andronicus of not sparing even his own relatives, giving orders for their punishment and at the same time shedding (according to Choniates) crocodile tears of sorrow. Thus for example Andronicus ‘put on trial Isaakios’ uncle Constantine Macrodoukas and Andronikos Doukas … A few days later these people were charged with the crime of lese majesty, despite the fact that they were the most eminent leaders of Andronicus’ party and the most powerful members of his faction, and his most devoted friends’ [140], p.303. They were both hanged [140], p.305.

Following this some of those close to Andronicus’ attendants asked him to take down the bodies of those hanged. After hearing their request not without displeasure, Andronicus asked if they died a while ago and after learning from the executioners that the wicked men perished said that he felt sorrow about these people’s fate. Having said that he burst into tears and added that the authority and the strictness of the law is more powerful than his personal affection’ [140], p.306.

By doing this Andronicus stressed, that no connections including friendship and family ties, even with the emperor himself, can waive the deserved punishment.

Choniates gives the following graphic example. According to Choniates in times of Andronicus there existed an old custom according to which a wrecked ship washed ashore was plundered by the locals. This strongly interfered with the trade and was bad for the state. Numerous strict edicts from the previous emperors could not change that. Therefore when Andronicus declared that he was going to stop this disgrace immediately no one believed him. However Andronicus issued a law decree according to which in the case of the wrecked ship being plundered the governor of that district where it took place would be hanged in that very place. The looting ceased immediately. Moreover, the locals began to help those who suffered the wreckage, provide them with food, etc. Nicetas Choniates writes about this: ‘Thus in the place of storm suddenly calm descended and this change was so unexpected that it seemed it was the work of something unworldly’ [140], p.338.

And once again we see an example of when Choniates discusses Andronicus’ actions he cites associations with the Gospels. Miracles, supernatural forces, placated storm, etc. We will remind you that the theme of the placated storm at the behest of Jesus is quite clearly present in the Gospels. ‘But as they sailed he fell asleep: and there came down a storm of wind on the lake; and they were filled with water, and were in jeopardy. And they came to him, and awoke him, saying, Master, master, we perish. Then he arose, and rebuked the wind and the raging of the water: and they ceased, and there was calm’ (Luke 8:23-24).

We would like to note that in the extract from Choniates given above his ‘Gospel narrative’ badly corresponds with the previous story of looted ships plunder. We are getting the impression that the more recent editor was trying to insert a Gospel narration about the subdued storm into some fitting place, but did not do it very successfully.

21. CHRIST IS A TEACHER AND A WISE MAN, ANDRONICUS IS A TEACHER AND A SOPHIST.

In the Gospels Christ is often addressed using the word ‘Teacher’. Such form of address occur dozens of times. See for example [108], p.1155.

When speaking of Andronicus Nicetas Choniates also uses this word although metaphorically: ‘Alike to a fierce TEACHER’ [140], p.332. No other Byzantine emperor was given such an epithet by Choniates.

Moreover Choniates directly calls Andronicus ‘a Sophist’, i.e. a man of wisdom. Besides the name of sophists was given to the ‘teachers of wisdom and oratory’ [22]. Choniates says: ‘He (Andronicus – Author) took to the epistolary tricks and like a SOPHIST came up with an unprecedented method’ [140], p.291. Such a characterisation of Andronicus fairly corresponds to the Gospel description of Christ, where he is presented as a man of wisdom and a teacher.

And again in the life descriptions of the Byzantine emperors such characterisation is unique or at least quite rare.