Part 1.

Russia as the centre of the “Mongolian” Empire and its role in mediaeval civilization.

Chapter 2.

Russian history as reflected in coins.

4. The origins of the bicephalous eagle as seen on Russian coins.

It is presumed that the bicephalous eagle symbol appeared on Russian coins in 1472 the earliest ([684], page 54). Its history is as follows. This symbol was first introduced by Ivan III in 1497 as the crest on his seal. Some historians explain it by Ivan III marrying the Byzantine princess Sophia Palaiologos in 1472. It is said to have come from Byzantium, which had also given Russia Christianity.

V. M. Potin concludes his analysis of how the bicephalous eagle made its first appearance in Russian heraldry as follows: “Apart from the rather unconvincing assumption of A. V. Oreshnikov about the symbol of the bicephalous eagle present on several XIV century coins, there is no factual information to confirm that it was introduced before 1472” ([684], page 54).

One may have drawn a line here. The hypothesis about the Byzantine origins of the bicephalous eagle seems perfectly natural and appears to raise no objections from any part. However, in the very next phrase V. M. Potin reports an astonishing fact:

“However, the XIV century inhabitants of the Eastern Europe were already familiar with the symbol, since it had been embossed on the Djuchid coins of Djanibek-Khan (1339-1357) and another anonymous mintage dated to 1358-1380 . . . It is currently impossible to associate the coinage of the Golden Horde [sic! – Auth.] bearing the bicephalous eagle symbol with analogous coins minted in Russia, since they are separated by a centenarian gap . . .

The epoch of Djanibek was the time when the currency of the Golden Horde flourished [sic! – Auth.], which is indirectly confirmed by the popularity of Djanibek-Khan’s coins. They remained in circulation for a long time after his death . . . The symbol was more characteristic for copper coins, with the Djuchids and the Russian Princes alike. It is most likely that after the marriage of Ivan III the Byzantine emblem found a fertile soil” ([684], page 54).

One cannot fail to notice that V. M. Potin is very cautious when he mentions this “delicate” subject. If we are to formulate the same thought frankly and explicitly, we shall see the following:

1) The bicephalous eagle first came to Russia with the coins of the Golden Horde in the XIV century.

2) It can be found on the coins believed to originate from both Russia and the Golden Horde. This is in good concurrence with our reconstruction, according to which the Golden Horde can be identified as the Great Russia, also known as the Volga Kingdom and Russia of Vladimir and Suzdal, qv in CHRON4.

3) It is possible that the Horde, or Russia, borrowed the bicephalous eagle symbol from Byzantium. The reverse is also a possibility – namely, that it was brought to Byzantium by the Horde and the Ottomans = Atamans.

4) Apparently, the bicephalous eagle first appeared on the coins of Djanibek-Khan regnant in the middle of the XIV century (1339-1357). Readers familiar with CHRON4 will instantly recognise this character as Ivan Danilovich Kalita (the First, 1328-1340). “Khan” translates as “Czar”, whereas Djanibek simply means John-Bek, or John (Ioann/Ivan). This corresponds with our reconstruction, according to which Ivan Danilovich Kalita = Caliph was described in various documents as Batu-Khan and Yaroslav the Wise.

5. The Tartar and Russian names of the coins circulating among the Russians and the Tartars.

The history of Russian coinage is well familiar with the word “altyn”, which is of a Tartar origin. The following is reported about its etymology:

“The word altyn was borrowed from the Tartar language, where it used to stand for a golden dinar . . . the first mention of altyns known from Russian sources was made in the treaty signed between Dmitriy Ivanovich, Great Prince of Moscow, and Mikhail Alexanrovich, Prince of Tver, simultaneously with the revival of Russian coinage and the introduction of denga as a monetary unit . . . the relation between the Old Tartar denke . . . and the Russian denga is obvious (towards the end of the XVIII century the N sound transformed into the softer version more common for the modern Russian) . . . Thus, altyn (likewise denga) was borrowed from the Tartar financial terminology” ([684], page 158).

Once again we become convinced about the unity of the Russian and the Tartar monetary system, which is perfectly natural for a single nation, or the Great = “Mongolian” Empire of Russia (the Horde). No terms were borrowed from anywhere, since it would be absurd for any to borrow from itself.

Here’s another curious fact. Let us, for instance, consider the native Russian word kopeika (kopek). V. M. Potin is perfectly right to point out the following: “There is no doubt about the fact that the name kopek derives from the Russian word for spear, ‘kopyo’, and had originally been associated with the figure of a horseman armed with a spear found on the Novgorod coins that became the foundation of Russian currency after the reform of the 1530’s”.

Yet further on Potin tells us the following: “However, Wilhelm Giese, a researcher from Hamburg, tried to prove this word to be of Oriental Turkic origin, supposedly translating as “dog” (“kopek” = “dog”). In Timur’s empire [sic! – Auth.] this name was used in a jocular fashion for referring to coins with leonine figures . . .

Although the connexions between the Russian state and the nations of Central Asia doubtlessly existed, and certain Russian words derive from Turkic, we consider the transformation of such a term into the name of a Russian coin of the XVI century quite inexplicable” ([684], page 160).

What have we just learnt from V. M. Potin? A most interesting fact indeed. If it is to be formulated briefly and explicitly, the currency used in Timur’s empire was called kopek, just like the Russian currency. This corresponds with our reconstruction, according to which Russia and the Horde (as well as Timur’s empire) can be identified as the same state.

The awkward explanation about the humble citizens of Timur’s great empire were calling their coins kopeks in mockery of the lion depicted upon them, calling it a dog, looks like a fantasy of the modern commentators forced to explain facts that fail to concur with the Scaligerian theory in some way.

Apparently, kopeks, or coins bearing the image of a horseman with a spear (hence the word kopeika, or kopek – the Russian for “spear” is “kopyo”) were circulating in the West as well as in Russia. There were many coins with images of mounted spearmen found during the archaeological excavations in Geneva, for instance ([1043]). We shouldn’t exclude the possibility that this fact can be explained by the Great = “Mongolian” conquest of the XIV century.

6. Russian and Tartar lettering and the presumably “meaningless inscriptions” on the ancient coins of the Muscovite principality.

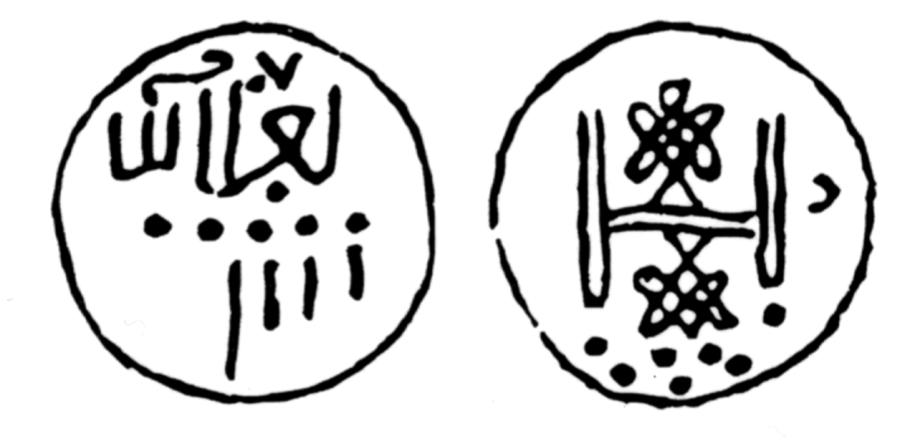

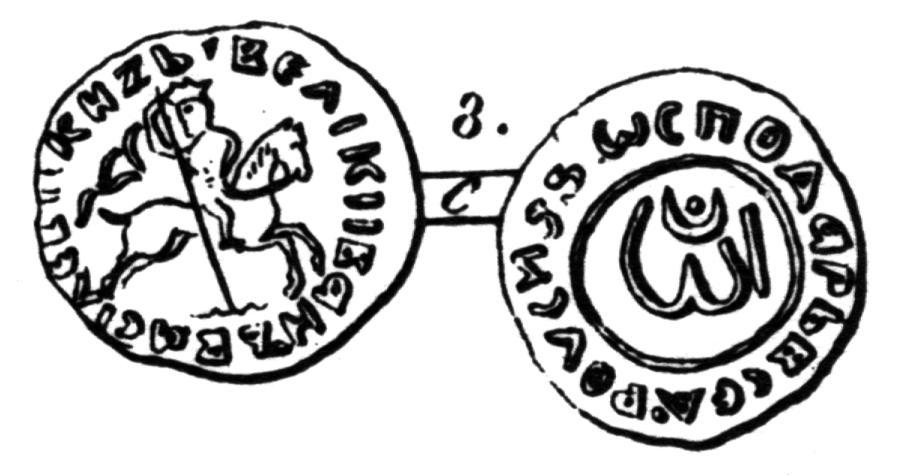

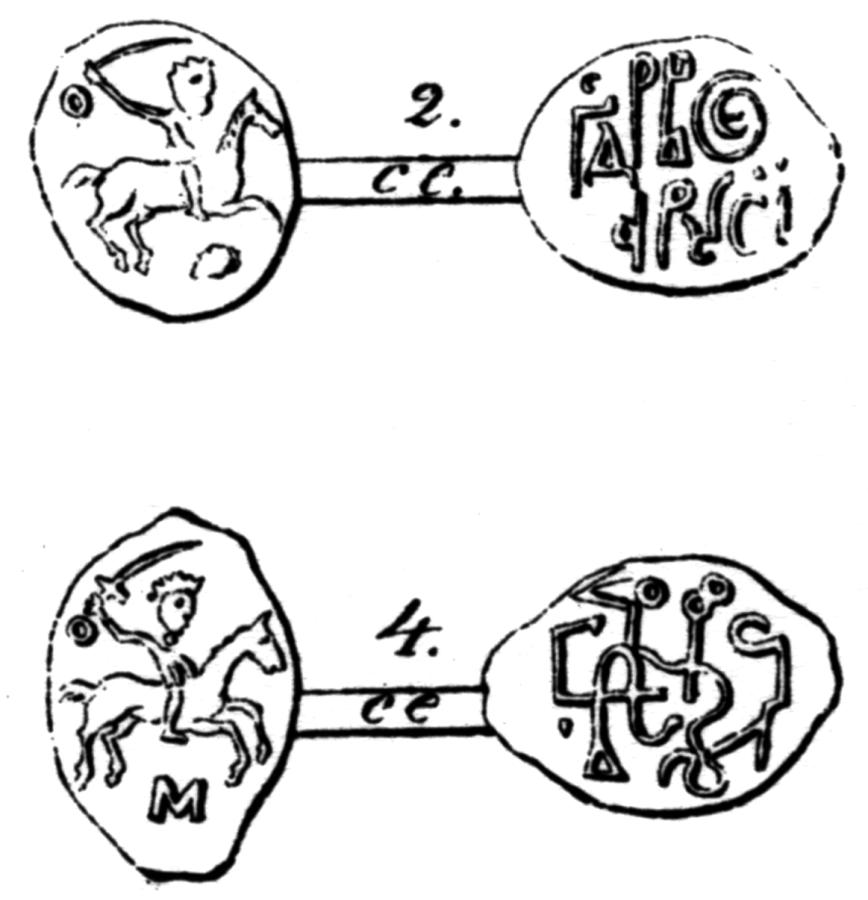

I. G. Spasskiy reports the following: “On one side of the first coins issued by the Muscovite principality we see the name of Dmitriy Donskoi in Russian; there is Tartar lettering on the reverse side, which settled on many coins of early emission in Moscow and its environs, as well as the principalities located further East . . . Tartar lettering as encountered on Russian bilingual coins, oftentimes meaningless or even illegible, were once considered a result of ‘conqueror and tributary’ interaction scheme” ([806], page 96). An example of such an “illegible Russian coin” is reproduced in fig. 2.13 below.

Fig. 2.13. “Illegible” inscriptions on Russian coins. The reverse of the top coin bears the legend “Lord of All Russia”. Could it be that the strange script as found on the reverse of the bottom coin means the same thing transcribed in a now-forgotten alphabet? Taken from [957], table VII.

However, as it was already mentioned in CHRON4, the term “illegible” is often used for referring to coins where the lettering could be read if it hadn’t contradicted Scaligerian chronology.

Further I. G. Spasskiy refutes the version about Russian princes being forced to place the Tartar lettering on their coins as vassals of the Horde. In particular, he points out that “even some of Ivan III’s coins minted in that epoch, when any meddling with the Russian currency was already right out of the question, we see Tartar phrases such as “The present is a Muscovite denga”, “Iban” (Ivan) etc” ([806], page 86).

According to A. D. Chertkov, “on the coin of Ivan the Terrible we see an Arabic inscription that complements the Russian; it transcribes his name as ‘Iban’” ([957], page 59).

Chertkov is therefore of the opinion that the Tartar lettering was still present on Russian coins under Ivan IV as well as Ivan III – at the very end of the XVI century, that is, which invalidates the theory about Russia being a tributary of the Horde. The latter no longer remained regnant in Russia, even if we’re to believe the Scaligerian and Millerian chronology. A. D. Chertkov believed that such coins were minted by the Russian princes for their Tartar tributaries, which actually makes sense.

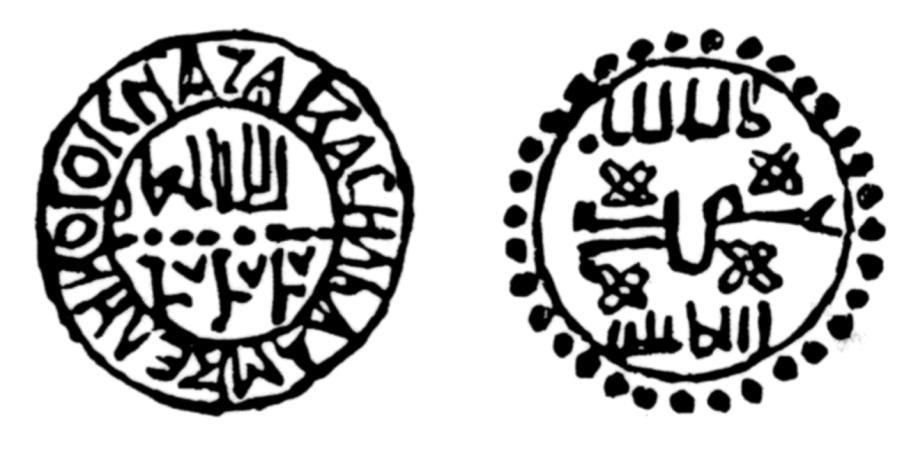

The “Tartar” lettering and “Arabic” symbolism as present on Russian coins (see figs. 2.5, 2.6, 2.7 and 2.14) are “consensually” (compulsorily, perhaps?) considered vestiges of the “Tartar yoke” in Russia. What one must remember in this respect is that one finds Arabic lettering on coins minted in the West of Europe, and not just Russia.

Fig. 2.7. Russian coin with the image of a Tartar tamga and an inscription in Arabic.

Taken from [870]. In reality, the inscriptions considered Arabic today

are set in one of the alphabets used in Russia before the XVII century,

now forgotten. See CHRON4, Chapter 13.

For example, “in the coins of Normandy and Sicily we see the word REX in Roman letters on one of the sides and Arabic on the flip side ([957], page 61). Let us remind the reader that much of the lettering found on Russian coins is also Arabic in origin ([957], qv above). Was there a Mongolian yoke in Sicily as well? Historians suggest other explanations – for instance, an abundance of Mohammedans in Sicily ([957], page 61).

We are well familiar with this double standard practice. The same postulations lead to different corollaries in reference to Russia and the West. If we apply the same logic to Russia, we can say that “there were many Mohammedans in Russia, hence the Arabic lettering occasionally found on the Russian coins”. This is the very explanation used for this effect by A. D. Chertkov (in [957], page 61), but only in application to the epochs postdating the end of the XVI century.

Our explanation of the Arabic lettering as present on Western European coins is as follows. The territories in question were part of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire in the epoch of the XIV-XVI century. The lettering was transcribed in the ancient Slavic characters forgotten today and presumed to be Arabian in origin.

Also, if we’re to assume that one side of the “Russo-Arabic” coins was Russian, and the other designed to represent vassal dependency, how are we to interpret the coin seen in fig. 2.7, with the legend “The Just Sultan Djanibek” written in the centre, and “Prince Vassily Dm” encircling it? See [870], pages 61-63.

Incidentally, even the Russian letters found on the Russian coins occasionally strike our contemporaries as extremely odd. Thus, the letter O, for instance, occasionally looked like a human profile facing right, whereas the letter H looked like an animal resembling a do ([957], page 120). See figs. 2.15 and 2.16.

According to the evidence of the experts in numismatic history, the overwhelming majority of the “Tartar” legends encountered on Russian coins (apart from the few exceptions as mentioned above) cannot be read ([806] and [957]).

In general, one might come up with the obvious question. How do we know that the “meaningless and illegible” legends found on Russian coins are indeed of Tartar origin? Could they simply have utilised some ancient Russian alphabet that had drastically differed from the more recent version known to us today? In CHRON4 we already mentioned the mysterious mediaeval Russian stamps covered in “meaningless illegible writing”. This writing turned out Russian – some of it at least.

Therefore, history of the Russian alphabet as reflected in our conception is very incomplete – apparently, up until the rather recent XVII century, completely different Russian letters and words had existed, cast into oblivion today. Are any modern researchers working on this problem? We know nothing about any such work.

In general, one finds that the numismatists are rather confused by the Russian coinage of the XIV-XV century ([806], page 97). “The Tartar lettering [on these Russian coins – Auth.], being of an imitative nature [? – Auth.], doesn’t offer us much for a precise identification of the coins, since all kinds of Tartar coins were used as prototypes for copies, without much distinction [? – Auth.] – oftentimes old ones, bearing names of long deceased khans [sic! – Auth.]” ([806], page 97).

All of this sounds highly suspicious. Could the great Russian princes, who had been free from the yoke of the Horde even in Romanovian history, have based their own currency on the ancient Tartar coins of long dead khans. We believe this hypothesis to be absurd. All the information related by I. G. Spasskiy concurs well with our reconstruction, according to which the Horde and Russia are but the same thing.

It is curious that modern researchers still haven’t managed to attain a full comprehension of the XIV-XV century Russian coinage. I. G. Spasskiy admits that “many Russian coins dating from this epoch remain unidentified; the names found upon them often defy all attempts to be linked to history. Other coins are altogether void of names, with nothing but the title inscribed upon them” ([806], page 97).

There are other examples to demonstrate that there is something wrong about the modern conception of the Russian language in the XIV-XVI century: “The lettering upon certain coins are still confusing – on many coins of Vassily Dmitrievich we see a distinct but incomprehensible inscription that reads ‘RARAY’” ([806], page 98).

Further also: “Many conjectures were voiced (some of them rather amusing) before it became possible to find a satisfactory reading of the unusual warning that we see on a certain type of early Tver coins: “Guard against a madman” ([806], page 98). However, Spasskiy doesn’t explain this truly odd inscription that one sees upon many Russian coins. Why would that be?

Also: “We are reminded of just as strange an inscription found on the Muscovite denga of Vassily Tyomniy: “Reject the madness, and ye shall live”.

Actually, there’s nothing too uncommon about it. Apparently, Russians had the custom of putting the first words of ecclesiastical texts on their coins (as it is done on reverse sides of crosses worn as pendants.

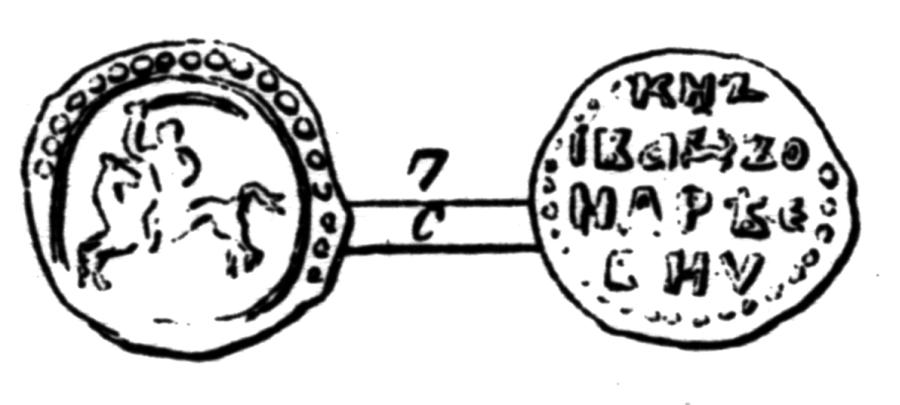

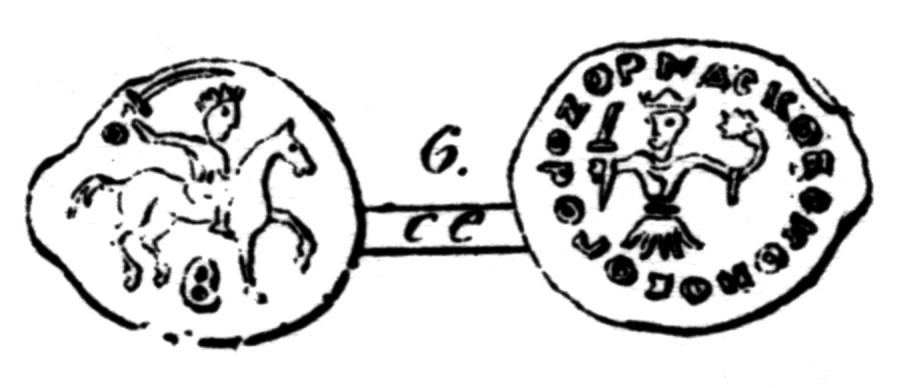

Further also: “a distinctly readable cryptogram [sic! – Auth.] that reads ‘DOKOVOVONOVOVODOZORM’ can be found on the famous type of coin that dates from the epoch of Ivan III or Vassily Ivanovich” ([806], page 98; see fig. 2.17).

M. I. Grinchouk points out the following about this coin: “The lettering is indeed very distinct, but hardly cryptographic – it can be interpreted as ‘Moskovsko-Novgorodskaya’, or ‘of Moscow and Novgorod’. Incidentally, the interpretation suggested by A. D. Chertkov in [957] is much closer to this version than to the ‘cryptographic’ one suggested above”.

All of the above means that these peculiar traits of the Russian alphabet and language in the XIV-XVI century need to be researched actively. Who is conducting this research, and where?

There are many such “cryptographic” coins. There must be something horribly wrong with the modern (Romanovian) version of Russian history, if we fail to understand the lettering on our national currency, which had still been in circulation some 100-200 years before the ascension of the Romanovs, and even during the first years of their reign.

I. G. Spasskiy tells us further: “One is particularly baffled by certain coins from Tver. They are decorated with figures of unidentifiable bipeds with horns and tails, much like the devils in folk tradition” ([806], page 99). Could this be the official national currency?

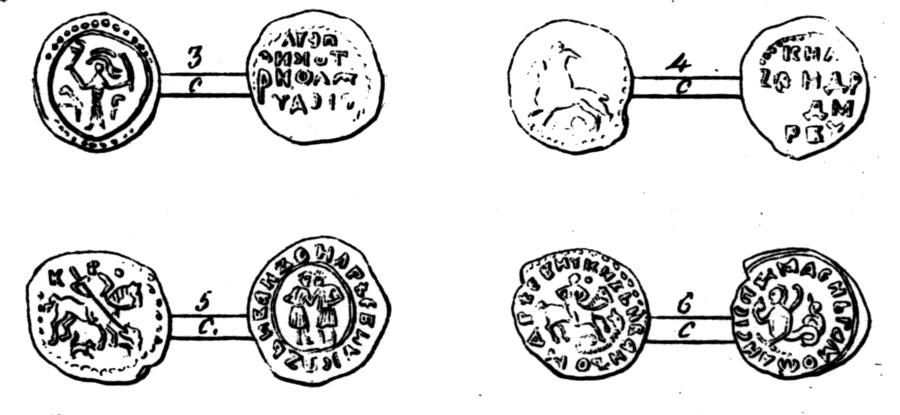

In the reign of Ivan III, “after the establishment of the 12-grain weight, all the quadrupeds, birds, flowers, griffins, sirens and other fruits of our minters’ imagination disappear from coinage . . . We are entering the epoch of uniform artwork, weight and general appearance, which shall henceforth characterize the money of the Great Prince of Moscow: a single stamp and the 12-grain weight shall remain in use for the next 150 years. We see a horseman riding to the right, with a sabre over his head, and four lines on reverse . . . the only difference is in the letters underneath the horse” ([957], page 48).

A. D. Chertkov doesn’t know the meaning of the letters underneath the horse – they could possibly represent the date – we use numeric characters nowadays, whereas our ancestors used the alphabet for the same purpose. It turns out that the life of Russia in the XIV-XVI century, emerging from the signs found on Russian coins, remains a mystery to us, if we cannot so much as make out many of the words used in the Russian language of that epoch.

It is assumed that the ancient Russian monetary unit called mortka was made redundant by the introduction of the denga as early as in the XIV century. However, I. G. Spasskiy makes the following unexpected statement: “The mortka is a surprising example of a term’s longevity: it was used in the region of St. Petersburg until the very beginning of the XVIII century, no less!” ([806], page 104).

Our hypothesis is as follows: the Russian monetary units that are dated to deep antiquity nowadays hail from a relatively recent epoch in reality; some of them remained in use until the XIX century.

7. Bilingual lettering on the Russian coins of the XIV century (Russian and Tartar).

According to what A. A. Ilyin, Corresponding Member of the USSR Academy of Sciences, reports in the catalogue entitled Classification of Russian Regional Coinage, “all the Russian coins minted at the end of the XIV century were issued on behalf of the Khan of the Golden Horde” ([309], page 33). What makes the historians and the numismatists arrive at this conclusion?

It turns out that “on the front side [of the Russian coins – Auth.] we always have a copy of the Tartar coin . . . the reverse side always bears the legend saying ‘Seal of the Great Prince’, or ‘Seal of the Prince’, as well as the actual crest. The name of the Great Prince appears to be a later addition . . . one is therefore brought to the conclusion that all the first Russian coins had two names” ([79], page 33).

Actually, the terms “front” and “reverse” as applied to coins are perfectly arbitrary. On the very same page A. A. Ilyin tells us that “in Russian numismatic terminology of said period the side that bears the seal of the Prince accompanied by Russian lettering is referred to as the front side, whereas the reverse is the copy of a Tartar coin” ([309], page 33).

Specialists in the field of numismatic history usually use the rather evasive term “doubly titled” for referring to these coins. In other words, they bear the name of a Tartar khan on one side and the name of a Russian prince on the other. However, Russian minters in their presumed ignorance would often use the name of the wrong khan. Consider this: “Russian minters, lacking a firm grasp on the Tartar language, appear to have used random Tartar coins as specimens” ([309], page 33). Apparently, this is why they would often mint coins with names and portraits of the wrong khans ([309], page 33).

It turns out that the savage Russian minters were completely unaware of just which Tartar coins were minted in their own day and age. Think of a modern Tartar with no knowledge of the Russian language, who is nonetheless perfectly aware of the nature of the Russian currency used for making purchases in shops, despite the numerous recent reforms.

We suggest a simple explanation. These coins weren’t “doubly titled”, but rather bilingual – that is, each coin would bear the name of a single ruler, who was simultaneously Khan and Great prince, in two languages – Russian and Tartar.

8. The locations of the Tartar mints.

Let us ponder another noteworthy issue. Where were the Tartar mints – the ones that minted actual Tartar currency? The Romanovian and Scaligerian version of history keeps silent about their possible locations.

On the other hand, we know the locations of the mints that produced Russian coinage (presumably copying Tartar specimens), or the Russian currency that had “looked Tartar”.

According to A. V. Oreshnikov, “due to the recurrent findings of uniform coins in a single region (the area around Suzdal and Nizhniy Novgorod), the question about the place where the Russian copies of the Tartar coins were minted is likely to be answered positively – they originate from the Great Principality of Suzdal and Nizhniy Novgorod” ([309], page 33). One gets the impression that the mints of Suzdal and Nizhniy Novgorod made the Tartar coins of the Russian khans, or Great Princes. On the other hand, we find Slavic lettering on the Tartar coins ([309], page 24). This makes the distinction between the “Russian” and “Tartar” coinage even more vague – apparently, it classifies as nonexistent.

9. Why Great Prince Ivan III put the Hungarian coat of arms on some of his coins.

There must be something out of order with the modern Romanovian version of Russian history if it allows for such events as the following. Apparently, when the Russian Prince Ivan III was minting his own coins, “he faithfully reproduced a common type of Hungarian coinage, complete with the Hungarian coat of arms on one of the sides and the figures of St. Laszlo on the other (mistaken for the Prince in Moscow). However, the Russian subscription contains the names and the titles of Great Prince Ivan, and his son and co-ruler, Ivan Ivanovich” ([806], page 109).

Let us reflect for a moment. It is very hard to imagine that a mighty ruler of the great Empire would for some reason put the coat of arms of a foreign country on his coins. One might well enquire whether this should imply that Hungary was part of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire of the Horde in the XIV-XVI century. At any rate, this hypothesis is more plausible than, say, the national Mexican coat of arms embossed on US dollar coins, with the profile of a Mexican hero placed on the reverse.

Furthermore, any textbook on mediaeval history states that the Mongols did in fact invade Hungary in the XIII century, at the very beginning of the “Mongol and Tartar invasion”. Scaligerian chronology dates this event to 1241, when the mighty army of Batu-Khan, or the Cossack Batka, laid waste the domain of Bela IV, King of Hungary ([677], page 8). The West was immersed in a state of panic upon learning of this.

In reality, it appears to have happened about a hundred years later, under Batu-Khan, also known as Ivan Danilovich Kalita, who reigned in the XIV century. Therefore, Hungary had been a colony of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire for some time.

However, as it is known to us even from recent history, in such cases imperial authorities usually minted special coins for their colonies. In our case, the Hungarian coins must have copied the Horde prototypes, using Hungarian symbols but indicating the title of the Russian Czar, or the leader of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, in Russian – “colonial coinage”, as it were. After the fragmentation of the Empire, Hungary had separated from the Horde (Russia), which naturally resulted in the cessation of such mintage.