Part 2.

China. The new chronology and conception of Chinese history. Our hypothesis.

Chapter 6.

Parallels between the history of Europe and the “ancient” China.

1. A general characteristic of Chinese history.

1.1. The reason why Chinese history is so complex.

Let us begin with two general observations.

Firstly, Chinese historical sources are extremely chaotic, contrary to the popular opinion.

Secondly, the modern Chinese pronunciation of historical names, personal as well as geographical, is drastically different from the ancient – and once we turn to the older versions of the names, we instantly begin to recognize names and terms familiar from European history.

According to J. K. Wright, “many of these Asian Christians bore Christian names, which have reached us in Chinese transcription – for instance, Yao-Su-Mu (Joseph) or Ko-Li-Chi-Sy (George; see [722], page 254). We can clearly see how Christian names transform in Chinese pronunciation and become distorted to a large extent.

It turns out that Yaosumu stands for Joseph, and Kolichisy – for George. If one isn’t aware of this fact beforehand, one is unlikely to ever figure it out on one’s own.

However, many of the modern ruminations about the uniqueness and the antiquity of Chinese history are largely based on this strong distortion of European and Christian names as pronounced in Chinese. It suffices to re-write the European annals transcribing all the names in the Chinese fashion in order to make the well familiar European texts impossible to recognise.

The general hypothesis related in the present part of the book can be formulated as follows.

Early history of China up until the XV century A. D. is in fact the history of Europe and the Mediterranean region – Byzantium in particular. Historical chronicles telling us about Europe were transplanted to China by the Great = “Mongolian” conquerors in the XIV-XV century A. D. the earliest.

Later on, already after the XVII century, these chronicles were discovered in China and erroneously assumed to report the “ancient history of China”. The mistake was easy to make, since the Chinese had used hieroglyphs, or simply drawings.

This method of writing must have come to China from Egypt, possibly as early as in the XII-XIII century. The interpretation of hieroglyphs is largely dependent on the language. The same hieroglyphs are read in completely different manners depending on whether the reader is Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese etc.

Names of people and places are transcribed hieroglyphically by means of finding similarly sounding hieroglyphs in the language in question. Therefore, the transcription, and, consequently, the modern pronunciation of the old Chinese names is initially dependent on the nationality of the author who had set them in hieroglyphs. One must estimate whether the author in question had originally been Chinese, Japanese or Korean.

Furthermore, human language keeps on changing. The names that had once been transcribed in one manner change into something completely different, even if the hieroglyphs transcribing it remain the same. Thus, the interpretation of hieroglyphs is time-related.

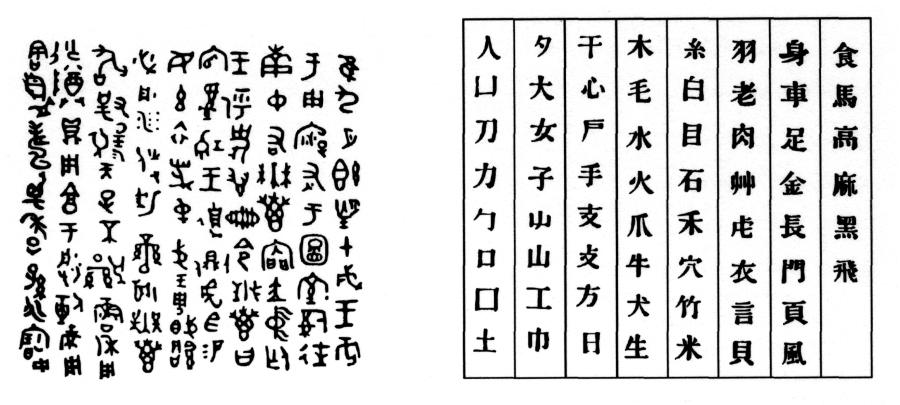

Apart from that, hieroglyphs have undergone a variety of reforms. The last large-scale reform of hieroglyphs in China and Japan already took place in our epoch – the XX century. Many of the old hieroglyphs are already impossible to read for someone accustomed to the modern hieroglyphic writing, which has undergone a multitude of changes. Fig. 6.1 demonstrates a comparison of the ancient Chinese writing and its modern equivalent.

The chaotic nature of Chinese historical sources is mentioned by specialists in a variety of respects. This is what V. L. Vassilyev, a famous historian, tells us:

“The first impression one gets after familiarising oneself with the complete collection of Chinese annals is a feeling of its completeness – it is easy enough to believe that anyone who knows the Chinese language can read the numerous volumes of historical works and mechanically extract data from them. However, the real picture is thoroughly different. Apart from the strange order of volumes that makes one go through the entire collection of chronicles in order to obtain information about a single event, tiresome labour and constant critical strain (which can nonetheless reveal the truth only after a study of the subject in its entirety), historians are constantly confronted with questions that keep them searching for answers in vain, running into lacunae and distortions all the time” (quotation given in accordance with [215], page 21).

The historian L. N. Gumilev adds the following: “The initial data come from the translations of Chinese chronicles, but despite the fact that said translations were done very diligently, the actual chronicles are a source of the greatest complexity” ([215], page 20). Further also: “Difficulties related to historical geography, ethnography, palaeography and social history are much greater than the ones listed [by Vassilyev – Auth.]” ([215], page 21).

Thus, we see that the Chinese chronicles are in a state of chaos and lack any sort of system whatsoever. It is easy to understand why. When old records transcribed in half-forgotten hieroglyphs were converted into a newer hieroglyphic system in the XVII-XVIII century, the translators were hardly capable of understanding the meaning of what they were translating. They were therefore forced to add much of their own commentary, which has led to a substantial growth of the source volume. This must have happened several times. Obviously, the chronicles turned out chaotic, confusing, and vague. Their vagueness results from the poor understanding of the old texts by the translators.

We have seen that European history was similarly afflicted, albeit to a lesser extent. European chroniclers would confuse personal and geographical names as well as certain terms – however, the phonetics of individual letters remained more or less the same. The situation in China was different, hence a much greater degree of entropy.

This is why historians accustomed to European materials become confounded when they begin to study Chinese history,

1.2. Chinese names of persons and places.

1.2.1. What we come up with when we read Chinese texts and translate Chinese names.

Chinese history appears to refer to a great variety of names and places familiar to us by the European history of the Mediterranean region. However, modern publications hardly give us an opportunity to see this. The matter is that we read old names using modern Chinese pronunciation, as it has been mentioned already, and without any translation to boot. However, N. A. Morozov was perfectly right to note that if one were to translate every single name that one finds in Chinese chronicles, the latter lose their distinct “Chinese” look as well as the ties with the territory of the modern China.

Leaving Chinese names without any translation whatsoever is incorrect, since they all have meaningful translations in reality.

N. A. Morozov wrote: “The readers have seen how the Highest Emperor, or simply His Highness, ordered his astronomers, two ‘Plans’ and a ‘Draft’, to wander the world in order to make astronomical and calendar observations [we have already quoted this ancient Chinese text after Morozov, qv above – Auth.].

Quite naturally, the readers themselves . . . decided that this wasn’t a chronicle . . . but rather a myth of a later origin . . . However, I have first read this myth in English . . . wherein ‘Draft’ and ‘Plan’ retained their Shang-Dung names of He and Ho, and the name of the Highest Ruler was left half-translated as Emperor Yao . . . This gave me the impression of a dry chronicle record whose every word is a historical fact” ([544], page 61).

One needn’t wonder about the mysterious reasons why one cannot make heads or tails of the Chinese chronicles translated quite as “meticulously”.

Another example: “In every Chinese story we read: ‘In the third century between 221 and 264 there were three emperors regnant in China simultaneously: Chao-Le-Di, Ven-Di and Da-Di . . . In the early IV century there was the dynasty of Shi-Chin, whose most spectacular ruler was known as U-Di . . . The dynasty regnant between 317 and 419 was that of Dung-Ching, whose kings were called Yuan-Di, Ming-Di, Chen-Di, Kung-Di etc”

N. A. Morozov writes: “Isn’t this account historical, documental and nationally Chinese? However, it is enough to recollect the fact that these names are transcribed as drawings and not sounds . . . for this pseudo-documental rendition to cease being authentically Chinese, let alone historical. We shall come up with the following:

‘In the third century between 221 and 264 the Mediterranean Empire was ruled by three emperors at the same time; their names were Clear and Passionate, Literary and The Great . . . The dynasty of Occidental Prosperity reigned in the beginning of the fourth century; its most spectacular ruler was known as the Military Emperor . . . After that, between the years of 317 and 419, there was the dynasty of Oriental Prosperity, whose rulers were known as The First Main King, the Fairest King, King of the Ending, King of Prosperity etc”

Further on Morozov asks the reader: “Do you think that a complete translation and not a partial one, which is the custom of every historian, as it was mentioned above, leaves anything of dry documental data, history or even distinctive national characteristics pertaining to China? The ‘Mediterranean Empire’ strongly resembles the empire of Diocletian in the Mediterranean region with its first triumvirate, only moved backwards by a few decades” ([544], page 62).

The pronunciation of names in Chinese has changed greatly over the course of time as well. L. N. Gumilev wrote the following in this respect: “Unfortunately, consensual pronunciations of Chinese names are based on the phonetics of the language that is contemporary to us and not the events in question. This circumstance complicates the linguistic analysis of ethnicons” ([215], page 151).

1.2.2. European nations on the Chinese arena.

*1) The “ancient” Chinese Hungarians.

The nation of the Huns was quite prominent in the “ancient” history of China. L. N. Gumilev even wrote the famous book entitled “Huns in China”. However, Scaligerian history reports that the very same Huns were active in Europe and the Mediterranean region in the beginning of the new era. Modern historians are forced to assume (and actually assume) that the Huns separated into two tribes, one of which ended up in the Mediterranean region, and the other, in China.

This is what L. N. Gumilev writes on this subject: “In the first century A. D. the kingdom of the Huns was split in two as a result of certain internal processes. One part submitted to the Chinese rule, and the other fought its way back to the West, having become mixed with the Ugrians and the Sarmatians” ([215], page 5).

It is easy enough to understand why the Huns have “become mixed with the Ugrians” when they arrived in Europe. This only happened on paper, in the reports of historians. As we mentioned in CHRON4, referring to Sigismund von Herberstein, mediaeval Hungarians (or Ugrians) were known as the Huns.

Hungarians also manifest in Chinese history under their European name, as Ugrians, or Ouigurs, which is virtually the same name ([212], page 165).

The progeny of the European Huns (in particular, their alleged Chinese roots) keeps the learned historians on edge. The Huns have recently become known as the Sunnians, in accordance with the modern Chinese pronunciation ([319], page 113).

For instance, S. S. Minyaev reports the following: “Finally, let us mention the historical destiny of the Sunnians [the Huns – Auth.] and the possibility of their advent to Europe . . . The primary reason that could have led to the possible migration of the Sunnians [the Huns – Auth.] and their transformation into the European Huns is usually named as . . .” ([339], pages 123-124).

S. S. Minyaev suggests a version that doesn’t even seem satisfactory to himself: “It is obvious that the suggested model doesn’t solve the problem of the Huns’ origins – au contraire, it emphasises its complexity” ([339], page 125).

We can therefore see that the “ancient” China was inhabited by Hungarians, but not just them – after all, a great many nations inhabited Europe in the Middle Ages, which is known to the readers perfectly well.

*2) Serbs in “ancient” China.

L. N. Gumilev reports: “In Asia, the Huns weren’t defeated by the Chinese – their conquerors belonged to a nation that doesn’t exist today, known as Sianbi in Chinese. In the old days, this nation was known as Särbi, Sirbi or Sirvi” ([215], page 6).

We categorically disagree with Gumilev about the non-existence of this nation. We all know the famous Serbs (also known as Särbi, Sirbi and Sirvi) – good warriors who still live in the Balkans and don’t intend to vanish at all.

*3) Goths in “ancient” China.

L. N. Gumilev tells us further: “Tribes of Zhundian origin [whose name is derived from the word ‘Zhun’, according to Gumilev, which is basically the same as ‘Huns’ – Auth.] united, forming the mediaeval Tangut nation . . . The Chinese sometimes called them ‘Dinlins’ figuratively; however, this name isn’t an ethnicon, but rather a metaphor that emphasises their European appearance as a distinctive trait. Real Dinlins were an altogether different nation and resided in Siberia, not China” ([215], page 30).

We are of the opinion that the name “Tangut” is easily recognizable as a version of the well familiar “Tan-Goth”, or simply “Don-Goth” (“Tanais-Goth”), which is the name of the Goths that lived in the area of the Don, or Tanais (the old name of the Don) – or, alternatively, near the Danube.

Thus, the Goths from the region of Don (or the Danube) lived in China, which is why the Chinese chronicles emphasise the European features of this nation. Another interesting detail is the claim that the Chinese Dinlins really lived in Siberia.

*4) The Don Cossacks in “ancient” China.

Above, and in CHRON4, we have repeatedly said that GOTHS - this is just another name for the Cossacks and Tatars. So, TAN-GOTHS, that is, DON COSSACKS, lived in CHINA. And therefore you can expect that continuing the fascinating reading of the Chinese chronicles, we will sooner or later stumble upon TATAR. Needless to say that our prediction comes true immediately. Indeed.

*5) Tartars and the Turks in “ancient” China.

Apparently, Chinese historians were convinced that the Tartars and the Turks were living in China since times immemorial ([212], pages 164-167).

“Wan Ho Wei is of the opinion that Chubu is the Qi Dang name of the Tartars . . . Their Turkic neighbours (the Blue Turks and the Ouigurs) called them Tartars, whereas the Muslim authors . . . called them Chinese Turks” ([212], page 165).

There were three primary kinds of the Chinese Tartars. “Mediaeval Chinese historians divided the nomadic Oriental nations into three groups: White, Black and Wild Tartars” ([212], page 167). This division of the Tartars into three groups is already known to us quite well, qv in CHRON 4. Namely, we are referring to the Great Horde, or Greater Russia, the Blue Horde, or Lesser Russia, and the White Horde, or White Russia.

As for the Chinese “Black Tartars”, one has to point out that there had also been Black Russia, which was indicated on the maps up until the XVIII century, qv above.

One must say point out the confusion that accompanies every mention of the Tartars, be it Europe or China. As we wrote in CHRON4, the word “Tartar” was a collective term in Russian history, which had applied to the Russians, the Turks and the actual Tartars in the modern sense of the word.

We see the same in Chinese history. L. N. Gumilev makes the following irritated comment in this respect: “What mystery does the ethnicon ‘Tartar’ conceal? . . . In the XII century . . . the term was applied to the entire populace of the steppes, from the Great Wall of China to the Siberian taiga” ([212], page 166).

The collective nature of the term “Tartar” was already pointed out by Rashed ad-Din: “Many clans sought greatness and dignity, calling themselves Tartars and becoming known under this name, just like . . . other tribes, who had possessed names of their own previously, but started calling themselves Mongols, attempting to cover themselves in the glory of the latter” ([212], page 166).

Further on, the Chinese Tartars appear to have undergone a series of fantastical metamorphoses. L. N. Gumilev reports that, apparently, “in the XIII century . . . the Tartars became regarded as part of the Mongols . . . the name of their nation ceased to exist in Asia and became used for referring to the Turkic tribes inhabiting the Volga region, subordinate to the Golden Horde, transforming into an ethnicon over the course of time” ([212], page 166).

“The Tartar multitudes (in a narrow sense of the word) were the avant-garde of the Mongolian army” ([212], page 166).

All of this is already familiar to us. All the inhabitants of Russia were referred to as “Tartars” in a broader sense of the word; however, Russia was also inhabited by the “real” Tartars, or the Turkic tribes living in the region of the Volga, or Tartars in the narrow sense of the word. Nowadays the term applies to them exclusively.

As we can see, the same was the case in China. The Chinese, just like the Western Europeans of the XIII-XVI century, confused the “Mongols”, or the Russians, with the Tartars, or the Turkic tribes inhabiting the area of the Volga.

We believe all the “Chinese reports” of the nations mentioned above, including the Tartars and the Mongols, to be European in origin. They were brought to China (on the pages of the chronicles) as recently as in the XVI-XVIII century, and then adapted so as to fit the vicarious version of the local history. This is how the Tartars appeared on the pages of Chinese chronicles, to vanish and miraculously reappear in the vicinity of the Volga later on.

*6) Swedes in “ancient” China.

Apparently, the North of China was inhabited by the numerous representatives of the Shi Wei nation, whose name can also be read as Svei ([212], page 132). Apparently, it is a reflection of the Swedes, who were formerly known as “Svei” in Russian.

The Chinese Swedes are said to have been a Northern nation, just like their European counterparts. Once again we see a name of a nation that still lives in Europe manifest in Chinese history as yet another phantom tribe that vanished mysteriously and without a trace a long time ago.

*7) Macedonians in “ancient” China.

The so-called “ancient Chinese history” contains many references to the nation of Qidani – the alleged descendants of the Syanbi, or the Serbs, qv above ([212], page 131). Furthermore, the Qidani are said to have been a South-Eastern Serbian tribe.

One can hardly get rid of the thought that the nation in question might identify as the Macedonians, the southern neighbours of the Serbs. The languages of the two nations are extremely similar, and the Macedonians were occasionally referred to as the Southern Serbs. We see complete correspondence with the “ancient Chinese geography”. The Qidani are said to have founded a state in China in the X century A. D. ([212], page 145).

By the way, what is the toponymy of the actual name China (“Kitai” in Russian)? According to L. N. Gumilev’s book, the Qidani were also known as Khitai, which is basically the same word as Kitai, and must be derived from the name Qidani ([215], page 405). Also, as we shall soon see from mediaeval sources, the name China (or “Kitai”) is most likely to be another version of the name Kitia (Skitia, or Scythia).

As we shall see below, the history of the Qidani is closely tied to the history of the “Mongolian” (Great) Empire. Historians also associate the Western European legends of the Empire of Presbyter Johannes, or the same Great Horde (Russia) with the state of the Chinese Qidani. All of it happens after the Qidani leave China for good. The nation famous in Chinese history strangely disappeared from the map of modern China ([215]).

We shall return to the history of the Macedonians, or the Qidani, somewhat later. For the meantime, let us just point out that the language of the Macedonians is believed to be the prototype of Church Slavonic, which had been used in Russia as the official language for a long enough time. Also, the actual creators of the Church Slavonic Cyrillic alphabet, the “Solun Brothers” Cyril and Methodius, are believed to hail from the city of Solun located on the territory of Macedonia, and are most likely to have been Macedonian. Thus, there are parallels between the ancient Russian culture and the Slavic culture of Macedonia.

It is interesting to compare this important circumstance to the fact that, according to the Chinese chronicles, the state of the “Qidani who had fled China” became the progenitor of the future “Mongolian” Empire, or The Horde (Russia), which we can identify as the Great Russian Empire of the Horde, whose centre was in the Volga region.

According to Orbini, a mediaeval author of the XVI century, “Jeremy the Russian, the learned historian, states it explicitly in the Muscovite annals that the Russians and the ancient Macedonians shared a single language between them” ([617], page 149).

Orbini refers to some “Muscovite Annals”. Did anyone see them? There must have been a great number of interesting materials written about the Russian history in the pre-Romanovian epoch. However, the Romanovian historians were laborious enough . . . Even the name of “Jeremy the Russian, the learned historian” disappeared from Russian history forever, as though he never existed. Old books burn well.

*8) Czechs in “ancient” China.

“In 67 A. D. the Huns and the Chinese were engaged in a hard battle for the so-called Western Territories. The Chinese and their allies . . . laid the state of the Cheshi, neighbours of the Huns, waste . . . The chieftain of the Huns gathered the Cheshi survivors and transplanted them to the eastern fringe of his land . . . The Cheshi belonged to the Eastern branch of the Indo-Europeans” ([212], page 163).

Not only do we see a reference to the European Czechs, but also a perfectly correct mention that they were neighbours of the Hungarians, or the Huns.

*9) The identity of the “ancient” Chinese Mongols.

References to the Mongol inhabitants of the Ancient China are unlikely to surprise anyone – the modern Mongols still live there, and the modern Mongolia borders with China. These Mongols belong to the Mongoloid race, as the name duly suggests. However, the “ancient Mongol” inhabitants of the ancient China were Europeans or Indo-Europeans, no less.

We learn of the following: “According to the evidence of their contemporaries, the Mongols, unlike the Tartars, were tall, blue-eyed and fair-haired, and wore beards” ([212], page 162).

Incredible. What became of them? The modern ethnic groups referred to as Mongols are completely different. L. N. Gumilev obviously wondered about this as well. He came up with a rather arbitrary theory aimed at providing the bewildered reader with an explanation of how the tall, bearded and blue-eyed “ancient” Mongols could have undergone a complete change of their racial type. We shall refrain from delving deep into his speculative constructions for a simple reason – we deem it unnecessary to explain it to the readers why the “Mongols”, or the Russians as mentioned in the “ancient Chinese” history were tall, fair-haired, bearded and, occasionally, even blue-eyed.

All of this leads one to the thought that the “Chinese history” before the XV century A. D. must reflect European events – to some extent, at the very least. Later on, the European chronicles ended up in China and became included into local history as its initial part. We already know of many such examples – this is how English history was created, for instance, qv in CHRON4. Chronicles of Byzantium and the Horde, relating the history of Europe and the Mediterranean region, were taken to the British Isles by the descendants of the crusaders who fled Byzantium after its fall in 1453, and then erroneously served as the foundation of the history of the British Isles.

2. The landmarks of the parallelism between the Chinese and the phantom European history

before the X century A. D.

We haven’t analysed the Chinese history before the X century A. D. in detail. However, even a very perfunctory study of the chronological table of Chinese history between the beginning of the new era and the X century A. D. (as cited in [215], for instance) leads one to the assumption that there might be a parallelism between Chinese and phantom Roman history of the epoch in question.

N. A. Morozov may have been correct when he wrote: “I would like to give a well-wishing recommendation to all those who use the Shang Dung or Beijing pronunciation when they interpret the Chinese hieroglyphs referring to the names of people and places, thus making the narration void of all obvious meaning . . . In your attempt to make the ancient documents found in Eastern Asia, which may have come there from Europe in many cases, look pseudo-scientific and authentically Chinese, you involuntarily deceive yourselves as well as others” ([544], page 63).

Pay close attention to the fact that the superimposition of Chinese and European history as discussed below does not contain any chronological shifts. Basically, European history simply became transplanted to the Chinese soil without any alterations of dates – the distortions only affected the names and the geography.

Furthermore, it is extremely important that the parallelism in question identifies Chinese history as the history of Rome in its Scaligerian version, or the very version of European history that already became extended due to the errors made in the XIV-XVII century by M. Vlastar, J. Scaliger and D. Petavius.

This instantly implies that the foundation of the “ancient Chinese” history was already based on the distorted version of chronology, which couldn’t have been created earlier than the XVI-XVII century; therefore, history of China as known to us today cannot predate this epoch.

Incidentally, this is in good correspondence with N. A. Morozov’s hypothesis, which suggests that the European chronicles that served as the foundation of the “ancient Chinese history” were brought to China by Catholic missionaries in the XVII century.

a. The phantom Roman Empire.

In the I century B. C. the “ancient” Roman Empire was founded in Europe by Sulla – its foundation is usually dated to the alleged year 83 B. C. ([327], page 197). We are told that from the very moment of its foundation, the Empire had been claiming its rights for world domination, which it strived to achieve via the conquest of neighbouring nations, which were correspondingly acculturated, qv in CHRON2, Chapter 6.

# b. China.

In the I century B. C. the famous “ancient” Han Empire was founded in China – “one of the four global empires of the antiquity” ([212], page 106). Its first emperor by the name of U reigned in the alleged years 140-87 B. C. ([212], page 105). The Han dynasty “strived to create a global empire via the conquests the neighbouring nations with the subsequent cultural inculcation”([212], page 106).

One’s attention invariably lingers on the comprehensive name of the first emperor – the simple and modest “U”.

Also, the “Chinese Han Empire” is most likely to identify as the Scythian Empire of the Khans, or the Russian Empire, also known as the Horde, governed by Khans.

a. The phantom Roman Empire.

The “ancient” Roman Empire of Sulla, Caesar and Augustus had initially been very successful in its conquest of the neighbouring nations. However, Rome eventually started to suffer defeats. During the reign of Marcus Aurelius, Roman Empire encountered powerful adversaries in the North – in particular, the nomadic tribes that had inhabited the region of the Danube, who managed to break through the border fortifications of the Roman Empire ([327], page 280). The reign of Marcus Aurelius, which falls on the alleged years 161-180, became “the epoch of fierce wars and economical depletion” ([327], page 326).

# b. China.

Around the same time, the Chinese empire of Han was implementing its plan of military expansion, unifying the adjacent territories under its rule. However, it soon ran into difficulties. “The war in the North didn’t merely turn out a failure – it had instigated a complete economical decline in China” ([212], page 106). In 184, the “Yellow Turban Rebellion” flares up in China, undermining the power of the Han dynasty ([212], page 106).

a. The phantom Roman Empire.

In the beginning of the alleged III century A. D., the “ancient” Roman Empire ceases to exist, swept over by waves of internal feuds and anarchy. The period of the alleged years 217-270 is know in Roman history as “the political anarchy of the middle of the III century. The time of the ‘Soldier Emperors’” ([327], page 406).

# b. China.

The Han Empire, presumably reigning in faraway China, ceases its existence around the same time ([212], page 106). The picture of its decline reflects the decline of the “ancient” Roman Empire, which is said to have taken place on the other end of the gigantic Eurasian continent, to the detail. “The initiative was taken over by the aristocrats, who divided into parties, and engaged into struggle against each other; most of them perished in fratricidal feuds” ([212], page 106).

“Illiterate and morally decayed soldiers seized the reins of power” ([212], page 106). The decline of the Han Empire is dated by historians to the alleged year 220 A. D. ([212], page 106), which postdates the decline of the Roman Empire by a mere 3 years.

We see the emergence of “soldier emperors” in both cases.

a. Phantom Roman Empire

After the collapse allegedly in the middle of the III century AD of "ancient" Roman Empire founded by Sulla and Caesar, power in Rome falls into hands of the famous woman - Julia Mesa, a relative of Emperor Caracalla [212], c.404-406. She covertly rules Rome and raises her henchmen to the throne. In the end, she is killed in the internecine fight allegedly in 234, see [327]. The time of her rule is characterized as exceptionally bloody. This woman is one of the phantom duplicates of the Gothic Trojan War of the XIIIth century. See the book "Foundations of History" and "Methods."

# b. China

Soon after the collapse allegedly in the III century AD of the Empire of Han (Khan) the power in the country, too, is taken by the wife of one of the Emperors, who was "energetic and ferocious" woman. She ordered the execution of the chief of the government, the father of the Empress Mother and his three brothers, marking thus the beginning of a new bloody era, see [215]. After some time she was killed. These events are dated in the Chinese history by allegedly 291-300 years AD. [215], c.41. Probably, "ancient Chinese Empress" and "ancient Roman Julia Mesa" are merely two different phantom reflections of the same medieval queen.

a. Phantom Roman Empire

Allegedly by the end of the III century AD, in the beginning of IV century AD after a period of severe strife begins a new phase in the history of the Roman Empire. This period is called The Third Roman Empire in the books "Foundations of History" and "Methods." This "ancient" Roman Empire begins approximately allegedly in 270 AD. See "Methods," Ch. 6.

# b. China

Allegedly in 265 AD, after the fall of the HAN dynasty in China, there appears a new JIN Dynasty. "The Roman Original" is copied, as we see, quite accurately. There we have allegedly 270 AD, and here it is allegedly 265 AD. Both phantom dates practically coincide. A new era is beginning in the history of China, as well as in the history of the "ancient" Rome [215], p.239.

a. Phantom Roman Empire

Allegedly at the beginning of the IVth century AD, Emperor Constantine transfers the capital to the New Rome and thus actually founds the Eastern Roman Empire - the future Byzantium. This is a well-known division of the "ancient" Roman Empire in the West - with the capital Rome in Italy and the East - with the capital in New Rome = the future Constantinople.

# b. China

Moreover, here, synchronously with the phantom Roman history, at the beginning of allegedly IVth century AD, and more precisely - allegedly in 318 AD – rules the new dynasty called Eastern Jin [215], p.242.

Thus, the Chinese Empire of Jin splits into two: Western Jin and Eastern Jin. Precisely as in phantom Italian Rome. Moreover, at the same time.

a. Phantom Roman Empire

"Antique" Rome at this time leads permanent intensive wars with the "barbarians" - Goths, Huns, etc. See "Methods", Chapter 6.

# b. China

China, in the same manner, fights "barbarians" at this time, and namely, with HUNS. Thus, the same Huns simultaneously attack the phantom Rome and phantom China, at different ends of the Eurasian continent.

It is impossible not to note the significant name of the capital of China at this time. It was merely and modestly called E. See [215], p.102.

a. Phantom Roman Empire

Under Theodosius I of the phantom Third Roman Empire allegedly in the IVth century AD, about 380 AD, Rome was forced to start an all-out war with Goths. The rebellion begins on the Balkan Peninsula. Goths inflicted a heavy defeat on the troops of Theodosius I. See "Methods," Chapter 6.

# b. China

Approximately at the same time in China of allegedly IV century AD begins a massive war with the TANGUTS, that is, as we have already explained above - with Goths. The uprising of the Tanguts dates to about allegedly 350 AD. [215], p.108. In 376 AD, Tan-Guts (the Don Goths?) conquest of the Empire of Liang.

Here it should be noted that in Chinese and Japanese the sounds of R and L do not differ. Also, the sounds of M and N, as we have already stated many times, are very close and quickly morph into each other. Therefore, the "Liang Empire" is merely "the Empire of the Ryam" or the Ram, that is, Rim, that is Rome. We see that Chinese chronicles directly speak about "Empire Rim."

After these events in China, "the steppe was administratively divided into Eastern and Western" ones [215], p.119. Doesn`t it resemble the great division of the "ancient" Roman Empire in Western and Eastern parts? Moreover, it happens that it was allegedly in the IVth century AD also, that is, precisely when (per the Scaliger chronology) the phantom Roman Empire also split. Seems there too many unbelievable coincidences with "ancient Chinese history" and "ancient Roman history"?

a. Phantom Rome Empire

"Pure Roman" Western Roman Empire is ended allegedly in 476 AD. The capture of Rome by the Germans and Goths under the leadership of Odoacer. This moment is considered to be the end of Western Rome. The last "purely Roman" Emperor was young Romulus Augustus, see "Methods," ch.6

# b. China

Allegedly in 420 AD Western Liang, that is, Western Rome, as we already noted, was conquered by the Huns [215], p.162.

"Chinese historiography announced the year 420 AD to be the breaking point separating the epochs [215], p.164. It is remarkable that the last Emperor of Western Liang (Western Rome?) was still very young [215], p.162.

However, after all, the "ancient Roman" Emperor Romulus Augustus was very young too, when his Empire collapsed under the blows of the "barbarians."

The Huns in the Roman Empire and the Huns in China

Allegedly in 460 AD in China, Huns were exterminated [215], c.200.

This event is strikingly identical with a similar one from phantom Roman history. Parallelism is so bright that even historian L.N. Gumilev couldn`t ignore it. Here is what he wrote: "Isn`t it strange that in these years (that is, the years of the death of Chinese Huns - Auth.) happens the same tragic end of the western branch of Huns. It is difficult to say that the chronological coincidence of the Asian Huns and the European Huns was an accident" [215], p.200. Of course, L.N. Gumilev tried to explain such fantastic coincidence somehow. He refers the reader to his theory of ethnogenesis. In our opinion, the matter is not in the ethnogenesis, but that the phantom European chronicles were laid in the foundation of "ancient Chinese history," even without a centenary shift in time.

Moreover, consequently, the same European Huns bifurcated. Some in Rome, others (on paper) moved to China. Better yet, at the same moment, they were defeated. Some were Huns defeated in the European reality, others - on Chinese paper.

Summary

Having become acquainted with the Chinese chronicles, we realized that, if wanted, spending a lot of time, this rough parallelism can be substantially deepened, tables of parallel events compiled, see the books "Foundations of History" and "Methods" for demonstrating the identity of the Second Roman Empire and the Third Roman Empire. We leave this work for future researchers of the real history of China.

The above data shows that "Ancient History" before the Xth century is probably a duplicate of the phantom "ancient European histories" of the epochs, thereby - in the erroneous version of Scaliger. Therefore this "Ancient History" could not have been written before the XVI-XVIIIth centuries AD.

3. Parallelism Key Points between the Chinese and Roman-Byzantium History of the X-XIVth centuries.

3.1. Parallels between the Macedonian Conquest in Europe and the Cidanian Conquest in China

We stopped above at the phantom VIth century. Let's skip the indefinite period up to the IXth century. After this, begins a new chapter in the history of China allegedly from 860 to the year 960 AD. That is approximately 100 years of darkness. L.N. Gumilev calls it "the dark age" and builds some geophysical theory that should explain the absence of records. The steppe dried up, and dusty hurricanes hit the unfortunate country. However, in our opinion, it is not in the tornadoes, but in the incorrect dating that hit.

L.N. Gumilev continues: "The great silence of the desert was widening, engulfed steppe and covered it with sand streams. That is why the chroniclers of the 10th century are silent about the events in the center of the continent. For A Long Time No Events Happened There "[212], p.152 This is the last blind spot in the history of China. The subsequent epochs are allegedly well documented [212], p.176.

As we have already seen, the "dark ages" of Scaliger's history are usually artificial junctions between neighboring chronicles, caused by their incorrect position on the time axis. In this case, chronologically, the last "dark ages," as a rule, mean the era of the beginning of a real written story, yet very poorly illuminated by the surviving documents. We have already repeatedly faced this in the analysis of the history of Europe. See books "Foundations of History," "Methods" and "New Chronology of Russia."

Therefore, we object to L.N. Gumilev: the events did happen. However, perhaps at another time and in a completely different place. Consider here those few legends, which came to us from the darkness of the Chinese history of allegedly IX-XI centuries AD.

Firstly, this is the legend of the conquest of China by the Cidan. This story, due to the imposition of the Cidans on the Macedonians = Ma-Cidans, naturally, one wants to compare with the legend of Alexander's Macedonian conquests.

Secondly, this is the legend of the Son of Heaven. The latter copies the narrative about Jesus Christ, mistakenly dated by the XIth century AD instead of the original XIIth century.

a. Mediterranean

The legendary founder of the vast Empire – Alexander the Macedonian - captured many countries in Europe and Asia, and created the Macedonian Empire. This is the famous Macedonian conquest. Becoming an omnipotent ruler, he, it is believed, adopted the customs of the Persian conquest, changed into Persian clothing, adopted sophisticated Persian customs instead of rustic Macedonian ones, etc. Immediately after his death, the vast Empire that has disintegrated, see "Methods." Ch. 8, Ch. 9.

Scaliger's history refers to Alexander the Great in the IVth century BC. However, we understand already that these events occurred, most likely, not before the 12th century of the new era, mainly in the 14th-16th centuries of the AD era.

# b. China

In the middle of allegedly Xth century AD, namely, in 946, Cidans under the leadership of Deguang have conquered all of China. In this case, the Cidan monarch "founds the Lyou's dynasty, the true Chinese one" [212], p.145.

Like Alexander of Macedon, "Deguang changed his costume to Chinese parade garments, surrounded himself with the Chinese officials, established in their country order more similar to the early feudalism, than to the old tribal one" [212], p.145.

However, soon after the victory, Deguang died. "As soon as the corpse of the conqueror taken to Manjoury, China revolted" [212], p.145. Empire disintegrated. In general, it is quite similar to the course of events taken by "antique" Alexander the Great.

3.2. Baptism in China and Russia in the Xth century

According to the New Chronology, see "Methods," Chapter 7, the activity of John the Baptist, and then Jesus Christ took place in the XIIth century AD. It is to expect that the trace of these famous events to be found in the "ancient Chinese chronicles" imported into China from Europe. The guess is correct. Such a trace exists, and very bright one.

Allegedly in the Xth century in China takes place a wave of the Baptisms of the local Nations to the Christian ritual. As, by the way, in Russia at the same phantom time.

“In the year 1009 Baptism happens to Kerait people, and at about the same time the Turkic-speaking Mongols have accepted the Christianity (Goths? - Auth.). At the same time were baptized the Guzs and some Chigils. Even among the Cidans and subordinate tribes of Western Manjou "some Christian element " was present, which gave rise to the emergence in medieval Europe of the legend of the Prester John.” [212], p.168-169.

We see that the name of the Prester John appears here. This is the reflection of John the Baptist and the Baptism associated with him. Also, it was at that time, "where it should be," that is, at the beginning of the XIth century. Recall that, see the "Methods," Chapter 7, that at this time in the history of Rome appears John Kristenious - one of the reflections of John the Baptist.

As we see John the Baptist appears, we guess that Christ will come very soon. Also, this prediction was also correct.

3.3. Son of Heaven In China in the Eleventh Century AD. Guildebrand as Reflection of Jesus Christ?

Indeed, in the middle of the phantom eleventh century AD in China appears Prince Yuan Hao, who proclaimed himself to be the "SON OF HEAVEN" [212] in 1038 AD, p.156. With his name is connected CHANGE of chronology, just as it was in the case of Jesus Christ, according to our reconstruction, see "Methods," Ch.7. Prince Yuan Hao "changed the Chinese chronology to his own; he immediately invented "[212], p.156. Furthermore, the "Chinese" Son of Heaven created new writing, "although hieroglyphic, but different from Chinese" [212], p.156.

The Son of Heaven was killed in 1048. However, after all, Gregory Hildebrand (the phantom reflection of the emperor Andronicus-Christ from XII century AD), according to the restored old (and erroneous for a hundred years) of the church tradition, lived precisely in this time - allegedly in the second half of the 11th century AD, see "Methods," Chapter 7. "Chinese date" 1048 AD practically coincides with 1053 or 1054 AD, from which in Europe, at least in some documents, is mistakenly introduced a new chronology. Recall here that Christ lived in 1152-1185. See our book "The Czar of the Slavs" (English page of the site chronologia.org) and the book "Foundations of History," Chapter 6, discussion of the chronological shift of 1053 years.

All this is reflected in the "Chinese history" of that time, which, in our opinion, is merely a "Chinese option" of the European history of the same period.

3.4. Reflection of the First Crusade In 1099 AD in the "Chinese History"

Furthermore, Chinese sources say that the Son of Heaven was killed in Tangut kingdom, that is - in our point of view- in the Goths one. It is consistent with the new chronology, according to which Jesus Christ (1152-1185) was, most likely, crucified in New Rome = Jerusalem = Troy in the XIIth century AD.

The new Rome is located in Asia Minor - the ancient Hettur [291], that is, country of Goths = Hets, see "Foundations of history." Ch.7.7.

Besides, the identification of Trojans and Turks with Goths is already well familiar, see "Methods," Ch.8. In general, the Balkans is a Slavic region with Turkish presence. Moreover, this, again and again, identifies this kingdom with Goths.

In Europe, immediately after the crucifixion of Christ (1185), allegedly in 1096 (the shift of 100 years) begins the First Crusade to The Balkans. Crusaders capture New Rome - Constantinople - Jerusalem and move farther to the south.

So in China at THE SAME TIME, after the death of the Son of Heaven, begins "the troubled time of the rule of the noble family of Lian... In 1082, the Chinese seized the fortress of Lianzhou from the Tanguts and reenthroned the old dynasty "[212], p.157.

In our opinion, the First Crusade of allegedly 1096-1099 AD is described here and practically without a shift in time. The "Chinese" dated this event by 1082 AD. The difference is only 15 years.

As we have already explained above that Lian is a Chinese pronunciation of the word RIM (Rome). Consequently, the "Chinese sources" speak here of the reign of the "noble family of the Romans." Correct.

Let us repeat once again that all these "Chinese events" refer to an era that is extremely poorly covered in "Chinese history," i.e., the period of 961-1100 AD. L.N. Gumilev called "the dark and empty period of the history of great steppe" [212], p.176. However, immediately after it begins the period, "full of events, names of heroes and cowards, names of places and Nations and even morally ethical assessments ... Sources for this era extremely diverse and characteristic" [212], p.176.

3.5. Century Shift in the "Chinese History" of the XIth Century

After the "dark period" begins bright parallelism between "Chinese" and European stories, but with a shift of 100 YEARS. Chinese dating is about a hundred years older than corresponding European. About this, see below.

3.6. Kaifeng as the Capital of the Chinese Empire "R"

At the beginning of the 12th century in China, we find the Liao Empire, i.e., without vowels - the Empire "R," since in the Chinese language the sound of R is replaced by L. Is not it Rome - Rim once again?

The capital of the Empire R is the city of Kaifeng. However, in Chinese chronicles, it is called for some reason, not Kaifeng, but Pian [1452]. Identification of the ancient capital of China as Pian with the modern city of Kaifeng is already some later hypothesis. Apparently – wrong.

3.7. Reflection of the Fourth Crusade in the "Chinese History"

a. Byzantium

In 1203-1204, the crusader Europeans attacked Byzantium and besieged Constantinople. This is an attack of the invaders; see in "Methods."

# b. China

In 1125, the capital of China, Kaifeng, is attacked by the invaders - Jurchens. The difference in Chinese and European dates is about one hundred years.

a. Byzantium

In the besieged Constantinople, the TWO PARTIES are emerging - supporters of the war and defenders of Alexei Angel, who arrived with the Crusaders, who are "fighters for peace."

The party of Alexei wins, and the Francs, the Crusaders, are promised to pay a hefty ransom. Crusaders move away from the city, see the book "New Chronology of Russia."

# b. China

Similarly, in the besieged Kaifeng, "two parties were created: supporters of the war and "fighters for peace." The latter prevailed, and the Jurchens withdrawal was obtained by paying the ransom and territorial concessions "[212], p.182.

a. Byzantium

In 1204 the situation changed, and the Franks lay again siege to Constantinople, capture it and take the Emperor Marchuflos (Murzufl), as a prisoner.

Theodore Laskaris becomes the Greek Emperor, who goes south to Nicaea, leaving Constantinople to plunder by the Franks.

# b. China

However, then the Jurchens come back and besiege Kaifeng the capital. “In 1127, Kaifeng fell, the Chinese Emperor was taken a prisoner, and his brother moved the capital to the south, leaving the people of northern China to looting by the enemy."[212], p.183.

a. Byzantium

The Franks put their Latin Emperor in Constantinople.

# b. China

The Jurchens plant their king in Kaifeng Altana = Altan-Khan [212], p.210. There is a definite sound analogy between Altan-Ltn and Latin ruler - Ltn, without vowels.