Part 3.

Scythia and the Great Migration. The colonization of Europe, Africa and Asia by Russia, or the Horde, in the XIV century.

Chapter 8.

West Europeans writing about the Great = "Mongolian" Russia.

6. A new look on the Kingdom of Presbyter Johannes.

6.1. Presbyter Johannes.

Let us return to the descriptions of Presbyter Johannes and his kingdom. As we have realised already, this kingdom most probably identifies as the mediaeval Russia, or the Horde, also known as the Great = “Mongolian” Empire. According to the mediaeval tradition, “Presbyter Johannes belonged to a very old genus, and was really a descendant of the Magi. It is possible that the tribes of his subjects were the same as the “infidel Turks of Benjamin of Tudela” ([722], page 254).

Thus, Presbyter Johannes is believed to have been the ruler of a Turkic nation. This concurs with our reconstruction, since Turkic peoples have naturally been represented among the citizens of the Great Empire, including the Turks. We must note that the “Magi” as mentioned above are most probably the same old Moguls, or “Mongols” (“Great Ones”).

J. K. Wright carries on as follows: “Available facts speak in favour of the theory that this account . . . is based on the rumours of some Christian Mongol ruler from Central Asia” ([722], page 254). According to Peillot, “whatever gave birth to the famous legend of Presbyter Johannes . . . it was linked to the famous Kereite Prince in the first half of the XIII century. It appears that all the Kereites mentioned in the history of the Mongolian dynasty were Christians – the majority at the very least. Indeed, marriages with Kereite princesses even brought Christianity into the family of Genghis-Khan ([722], page 254).

Further we learn that “Marco Polo and many other travellers of the XIII century tell us that Mongolian princes often got baptised, although [as Wright hastens to assure us – Auth.] it is more likely to be explained by their indifferent attitude towards religion than by earnest religious convictions” ([722], page 255).

Thus, the researchers of today are forced to make vague assumptions in order to explain the constant contradictions between the evidence contained in the ancient documents and the Scaligerian history textbook. The real itinerary of Marco Polo shall be discussed in Part 4.

6.2. European names distorted beyond recognition in later Chinese transcription.

Although we have already written a great deal about China, the account of J. K. Wright brings us back to this fascinating topic. Let us quote from Wright once again: “Many of these Asian Christians bore Christian names that have reached us in Chinese transcription, for instance, Yao Su Mu (Joseph) or Ko Li Si Tsy (George), qv in [722], page 254. We are therefore given a rare opportunity of acquainting ourselves with the Chinese transcriptions of Christian names.

In Part 2 (“China”) we state that many of the modern ruminations about the great antiquity of Chinese history are largely based on the substantial distortion of European and Christian names in Chinese transcription. It suffices to rewrite a European chronicle in Chinese in order to make it impossible to recognize – a text that uses “names” like Kolisitsy, Yaosumu etc in lieu of George, Joseph and so on shall definitely look Chinese to anyone, with nothing in common with the familiar European original.

6.3. Europeans called China “Land of the Ceres”.

“In the ancient times the Chinese were known as the Ceres” ([722], page 243). Mediaeval Europeans believed Ceres to be “a city in the Orient that has given its name to that region, as well as a nation and a type of fabric” ([722], page 243).

Many mediaeval chronicles refer to China as to “The Land of the Ceres”. Who are these Ceres? Without vocalisations we have SR or RS (seeing as how names and words in general could be read in both directions – left to right, in the European manner, or right to left – the Jewish and Arabic way). But the name RS is likely to stand for “Russia”, which brings us to the obvious hypothesis that the Ceres can be identified as the Russians.

This is perfectly understandable – according to Scaligerian history, China, or a large part thereof at least, belonged to the “Mongolian” Empire, or, as we realise now, the Russian Empire, or the Horde, of the XIV-XVI century. Moreover, we have found out that the name “Kitai”, which stands for “China” in modern Russian, used to refer to Scythia in the Middle Ages.

Wright tells us further: “Only in the XVI century it became clear that the land of the Ceres and China were really the same country” ([722], page 423). The name Syria = Assyria = Ashur must have the same root. When read in reverse, it transforms into Russ, or Russia. Syria and “Land of the Ceres” are also synonymous.

Furthermore, “China” was known under the following names in the Middle Ages: Land of the Ceres, Land of Xing, Land of Sin, Thiema (? – see [722], page 243) and Thinae ([722], page 251). Let us point out that Thinae once again associates with Tana, the land of Tanais (or the Don).

6.4. The famous mediaeval “Epistle of Presbyter Johannes” as an authentic document describing the life of the ancient Russia, or “Mongolia”.

An important mediaeval text has reached our day that gives us the opportunity of a fresh look on the true history of the Great Russia. Historians dated it to the XII century: “The earliest manuscript . . . dates from 1177 the earliest” ([722], page 255). Unfortunately, Wright does not mention the identity of the person who dated the “epistle of Johannes” or the time and place of this chronological research. Do we have the original of the letter at our disposal today? Apparently non – otherwise, why would Wright mention nothing but “early manuscripts”, or copies? Also – what language was the original written it? The last question is of interest as well; as we shall see, the nature of the text leads us to the thought that the letter in question dates from a much more recent epoch.

Needless to say, historians believe this document to be “mediaeval fiction”, albeit “doubtlessly famous” ([722]). We shall be treating it differently, since we are beginning to realise that despite its somewhat propagandist orientation, the famous Epistle of Johannes is based on real events from the authentic history of the ancient Russia.

According to Wright, “the most detailed description of the kingdom of Presbyter Johannes is contained in his ‘Epistle’, addressed to the Byzantine emperor Manuel (Comnene) according to some of the chronicles and Emperor Frederick or the Pope according to other sources.

In this letter, whose earliest manuscript dates from 1177 the earliest, Johannes claims that his wealth and power are greater than those of any kings in the world. He is in command of the three lands of India and the sepulchre of St. Thomas. His kingdom spreads over the Babylonian desert all the way to the Tower of Babylon; it comprises seventy-two provinces, each of which is governed by a king. Amazons [we have mentioned them in CHRON4 – Auth.] and Brahmins are all subordinate to the Presbyter. It takes four months to cross the territory of the kingdom in a single direction . . .

This kingdom, abundant with milk and honey, has many wonders. One of the rivers of Paradise flows through it; one finds gold and gemstones in the rivers of this kingdom. Pepper is harvested here . . . another wonder is the mysterious sea of sand, with a stony river flowing into it. Behind it one finds the lands of the ten Jewish tribes, which are subordinate to a mighty Christian ruler, although they have got kings of their own” ([722], page 256).

Wright continues: “An early Latin manuscript entitled ‘Letters’, which must have been written in England [sic! – Auth.], reports that there were people of every nationality at the court of Presbyter Johannes. There were Englishmen among his personal servants, and every Englishman who came to the palace was initiated into an order of knights, whether knight or cleric” ([722], pages 255-256).

It is possible that the Englishmen mentioned herein had really hailed from the British Isles. On the other hand, we must recollect the hypothesis formulated in CHRON4 about the term “English” initially referring to the inhabitants of Byzantium in the epoch of the Angeli, a famous imperial dynasty regnant in Constantinople. Could it be that these “Englishmen” from the Letter of Johannes are but close neighbours of the Horde harking from the Byzantine Empire.

It must be noted that the Kingdom of Johannes was well respected in the Western Europe. At any rate, Wright tells us that “throughout the whole XIII century the Pontiffs and the Christian monarchs of the Western Europe strive to make contact with some strong nation in the East, be it the Mongols or Presbyter Johannes – all in vain” ([722], page 256). As we realise today, the Mongols and the subjects of Presbyter Johannes can really be identified as a single nation, namely, the Great (“Mongolian”) Russia.

Another document worthy of our attention is as follows. It is the letter sent by Pope Alexander III to Presbyter Johannes, the Great King of the Indians and the Holiest of Clerics (Magnificus rex Indorum, sacerdotum sanctissimus). The Pope sends an envoy in order to “explicate the postulations of the Occidental Christianity to the Presbyter in order to convert him into the true Catholic doctrine” ([722], page 256).

Below we shall cite some familiar linguistic data concerning the meaning of the word “India”, which turns out to be a mere synonym of a “faraway land”, which makes “Indians” the denizens of some distant country, and their king, a “Great King of a faraway land”, whose identity remains open for interpretation.

Before we can approach the next section, let us recollect that, according to the famous mediaeval Biblical tradition, there are “four rivers flowing through the Paradise”. The location of the latter is also an issue of great interest (where does one find the “Rivers of Paradise”, for instance?) The topic was famous in mediaeval science and literature – there was a multitude of opinions, voiced at many a debate.

6.5. The river of Paradise flowing through the kingdom of Presbyter Johannes.

6.5.1. The two rivers: Don and Edon.

According to the Epistle of Presbyter Johannes, one of the rivers of paradise flew through his Kingdom. Which one? According to a report of J. K. Wright, “the river of Edon is mentioned in the Epistle of Presbyter Johannes as one of the heavenly rivers floating through a pagan province of this great Christian ruler’s kingdom, covered in a multitude of its tributaries” ([722], page 245).

If the Kingdom of Presbyter Johannes identifies as the Great Russian Empire, what is the identity of this River Edon? It might well be the Don, or, alternatively, River Volga. Some modern historians believe it to be the River Indus in modern India. We don’t feel like arguing – this kind of identification is also valid, since most of the modern India was indeed part of the Christian Kingdom of Presbyter Johannes, according to the same old Scaligerian version of history.

However, some historians remain unconvinced about the identification of Edon as Indus. Some believe the name to be an “obvious reference to Ganges or Physon” ([722], page 245). But if the “Indian Kingdom of Presbyter Johannes” identifies as the mediaeval Russia, or the Horde, river Edon flowing through this kingdom is likely to identify as the Don or the Volga.

6.5.2. River Volga was also known as “Don”.

Our opponents might counter that according to our very own hypothesis, the capital of the Presbyter’s Empire was in Novgorod the Great, or the area that comprises Yaroslavl, Kostroma and Rostov. However, Yaroslavl stands on River Volga. How can it possibly be the Don at the same time?

Our reply may surprise the readers accustomed to the idea that the name Don has been used for referring to just one river (the modern Don) since times immemorial. In CHRON4 we explain that the name Don could apparently refer to different rivers back in the day, being a mere synonym of the word “river”. This fact is known perfectly well to the specialists (see this topic discussed in CHRON4).

Volga was indeed known as Don. Indeed, let us recollect the Hungarian chronicles and the formula “Ethul id est Don” used therein – River Ethul (Ithil), that is ([866], page 529).

6.5.3. River Physon and Russian River Teza.

According to one of the known beliefs, the river flowing through the kingdom of Presbyter Johannes was called Physon, which is occasionally identified as Edon (see [722], page 245). However, a river that one might identify as Physon can be instantly found in Vladimir and Suzdal Russia – we are referring to River Teza, a navigable tributary of the Klyazma, located at the distance of some 90 kilometres from Yaroslavl ([995]). It might be the very River Physon, especially considering the frequent flexion of Ph (F) and Th (T).

The environs of the Russian River Teza are located at the distance of circa 100 kilometres from Yaroslavl; many of the old Russian cultural centres can be found here. For instance, the ancient Russian city of Shouya stands right on the banks of the Teza. It had already existed in the XIV century; in the XVI-XVII century this city was known as a large craft and trade centre, immediately related to the Volga trade ([85], Volume 48, page 242). The famous Boyars Shouyskiy were the descendants of the mighty Princes of Shouya ([404], page 52). At the end of the XVI century they prevailed in the Boyar Duma, and one of them, Vassily Shouyskiy, even managed to become Czar for a short while.

Also, the famous ancient village of Palekh lays some 30 kilometres away from Shouya, widely known as a centre of Russian art, temporal as well as ecclesiastical (we are referring to the famous folk tradition of lacquered miniatures and the school of icon art that hail from these parts).

6.5.4. River Volga (or Ra) as a “river of paradise”. Rai as the Russian for “paradise”.

Now we can also attempt to take a fresh look at the mysterious river of paradise flowing to the kingdom of Presbyter Johannes. The river that flows through Yaroslavl is Volga, which was known as Ra in the Middle Ages.

Volga was referred to as “Ra” by many “ancient” authors of the Middle Ages – in particular, Ptolemy, as well as numerous other “ancient classics” who wrote about this river. River Ra is Volga; it is also likely to identify as the “river of paradise (Rai)”.

Incidentally, the Mordovian name of the Volga is still Rav, or Ravo ([866], page 337). Let us also note that the name “Ra” as applied to Volga was transcribed on the maps as “Rha” ([90], page 150; see also the relevant fragment of the ancient map reproduced in CHRON2, Chapter 4:1.1). The Romanised version “RHA” is distinctly similar to the Russian original (“reka” – “river”).

Thus, we have discovered a number of important names mentioned in the Epistle of Presbyter Johannes in the historical geography of the ancient Russia – right where they were supposed to be according to our reconstruction (in the immediate vicinity of Novgorod the Great, or Yaroslavl).

6.5.5. The birthplace of Presbyter Johannes.

It would be interesting to find out about the birthplace or the place of residence of Presbyter Johannes, also known as Ivan Kalita and Batu-Khan. We can give no definite answer to this question so far, but we aren’t to rule out the possibility that it was the famous village (and now city) of Ivanovo, whose name might be derived from the name Johannes (Ivan, or Ioann).

The city of Ivanovo is located on the site of an ancient village, also named Ivanovo – incidentally, in the immediate vicinity of River Teza, or Physon, which we have just mentioned, at the distance of some 20 kilometres from it ([995]). The village was known as Ivanovo up until 1871. Between 1871 and 1932 its name was Ivanovo-Voznesensk; currently, the city of Ivanovo is the regional centre of the Ivanovskaya Oblast. Ivanovo has been widely known as a centre of weaving industry ever since the XVII century. Up until 1741 the village of Ivanovo had belonged to the Princes of Cherkasskiy, and then to the Counts of Sheremetev ([85], Volume 17, see under “Ivanovo”). Nowadays it is a large city in Central Russia.

6.5.6. Khulna, the capital city of the Presbyter’s kingdom, identifiable as Yaroslavl, or Novgorod the Great (also known as Kholmgrad).

J. K. Wright reports the following, quite amazed: “A strange event that occurred in Rome in 1122 fuelled the fire of the popular belief in the existence of a large Christian populace in Asia. There is an anonymous report about a certain Indian Patriarch called Johannes visiting Rome that year. The visit was perceived as a colossal sensation by the Papal Curia and indeed the whole of Italy. According to the reporter, there had been no visitors from those remote and barbaric parts in Italy before that occasion, nor did any Italians travel there . . .

He [Patriarch Johannes – Auth.] told the Papal Curia a great deal about his homeland. He described the capital city of Khulna situated on the Physon, one of the four rivers of Paradise, as a colossal city surrounded by tall walls and populated by true Christian believers. Outside the walls there was a mountain surrounded by a very deep lake, with a church on its top, devoted to St. Thomas. He also mentioned the existence of twelve monasteries around the lake, built in honour of the twelve apostles. The Church of St. Thomas was only accessible once a year, when the waters of the lake parted, allowing the pilgrims to approach the holy place” ([722], pages 249-250).

Actually, another report of this visit states that Johannes claimed “the Church of St. Thomas to be surrounded by a river and not a lake. Said river would dry up for eight days before and after the day of this apostle’s holy feast” ([722], page 250).

We are likely to be confronted by relatively recent fantasies of some XVII or XVIII century author. It goes without saying that we could have written them off as tall tales told in the Middle Ages, which is what modern historians actually do. And yet – could it be that these legends were based on true facts as perceived and interpreted by a later chronicler, with fantasy hues making up for the paucity of data? Let us study this mediaeval text more attentively and attempt to decipher the information contained therein.

And so, what can we say once we re-read this nebulous account?

The text reports the existence of a gigantic capital city on the banks of River Physon, which historians identify as Edon, whereas our reconstruction suggests the river in question to be the Don, or the Volga, or the Teza. The name of this city is Khulna, or Khulma – obviously the Russian word for “hill”, which is “kholm”, taking into account the frequent flexion of M and N in the ancient texts. Also cf. the Old German word for “hill”, “hulma” ([866]). What city could it possibly be?

Was there any city called Kholm or Khulm? Let us voice the following hypothesis. It might be the Russian city of Kholm-Grad (or Khulm-Grad), which we wrote about at length in CHRON4. The city has been quite famous for a long time, and known to every historian under the name of Novgorod.

In CHRON4 we claim that Kholmgrad, or Novgorod, can be identified as Yaroslavl on River Volga, which was also known as Don, likewise many other large Russian rivers. River Physon, which we suggest to identify as River Teza, is one of Volga’s tributaries. According to our reconstruction, Yaroslavl (also known as Novgorod and Kholmgrad) was the capital of the Great Horde. Johannes explicitly refers to the city of Khulna as to a capital, qv above.

In other letters sent to foreign heads of state (the Byzantine Emperor Manuel, for instance) Presbyter Johannes calls the City of Souza Capital of his Empire, or the Three Indias ([212], page 83). We thus have another capital, which may have existed alongside Khulna or served in this capacity in another epoch. The capital may have been moved, as well – the somewhat elliptical nature of the ancient text is rather obvious to us.

Today we are told that the “ancient” city of Souza was the capital of the ancient state of Elam in Mesopotamia – on Persian territory, that is. Historians date the heyday of Souza to the alleged IV-VI century B. C. ([212], page 455). Needless to say, there is no such city anywhere in modern Persia. Furthermore, historians themselves concede that the epistle of Presbyter Johannes clearly refers to some other place than Mesopotamia. L. N. Gumilev exposes the author’s ignorance with indignation: “Only someone entirely unfamiliar with the ancient geographical literature in general could fail to notice that the author of the letter is unable to make head or tail of geography” ([212], page 83).

The “ancient” Souza has therefore vanished without a trace. Yet the Russian city of Suzdal, the former capital of Vladimir and Suzdal Russia, exists to this very day – it is actually very close to the city of Ivanovo, qv above. We haven’t managed to locate any other likely heir of Souza on any modern world map.

Our reconstruction is as follows. Souza, the ancient capital of the Kingdom of Three Indias ruled by Presbyter Johannes, is likely to identify as the famous ancient Russian capital city of Suzdal located right next to Vladimir, whereas the Three Indias are the Three Hordes (later to become the three Russian lands – Greater Russia, Lesser Russia and White Russia). As for Persia, let us recollect that the word “pars” (“part” in the meaning of “land”) could refer to any geographical area at all, qv in CHRON5, Chapter 1:4. Moreover, prior to its relocation to Asia, the word Persia may have stood for P-Russia (Prussia), or B-Russia (White Russia, or Byelorussia).

6.5.7. The description of the flood on the great Indian river Volga in the epistle of Presbyter Johannes.

Next Patriarch Johannes tells us about the Church of St. Thomas, which is only accessible when the river that surrounds it runs dry. Let us recollect that the Holy Feast of St. Thomas falls on the springtime of the year, or the next Sunday after Easter. What happens to rivers in spring, especially to the Volga and its tributaries? They tend to overflow, and the floods on the Greater Volga and all the rivers that flow into it are particularly famous. These floods on the Volga may have made some church in the environs of Yaroslavl inaccessible for a certain period of time each year.

This might be what Patriarch Johannes was really speaking about. His words could have been misunderstood and misinterpreted by the listeners and the chroniclers – for example, they somehow managed to get the bizarre notion that the church was only accessible once a year. Nowadays we have to separate the factual kernel from the rind of fantasy as a result.

6.5.8. Which church is famous for the “parting of the waters” around it on the Feast of St. Thomas?

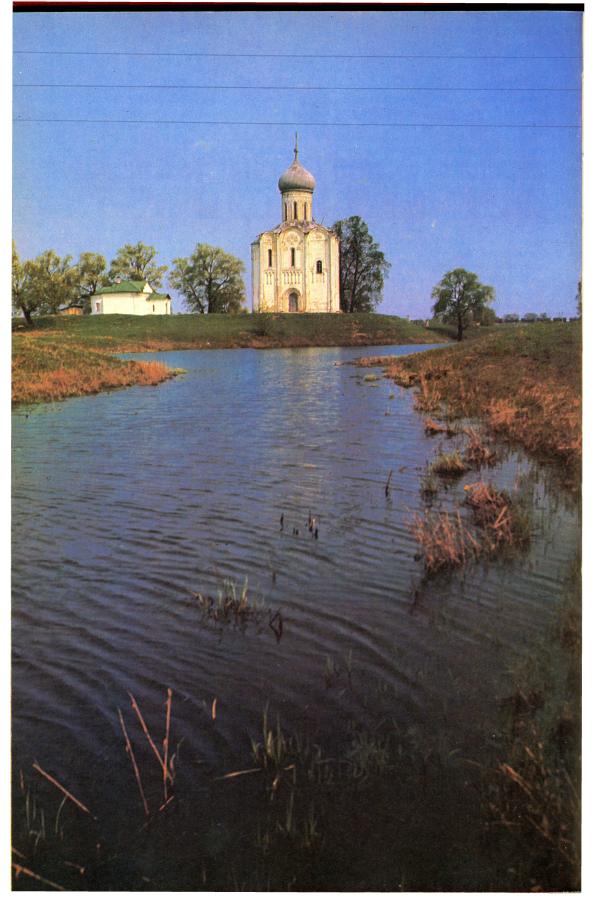

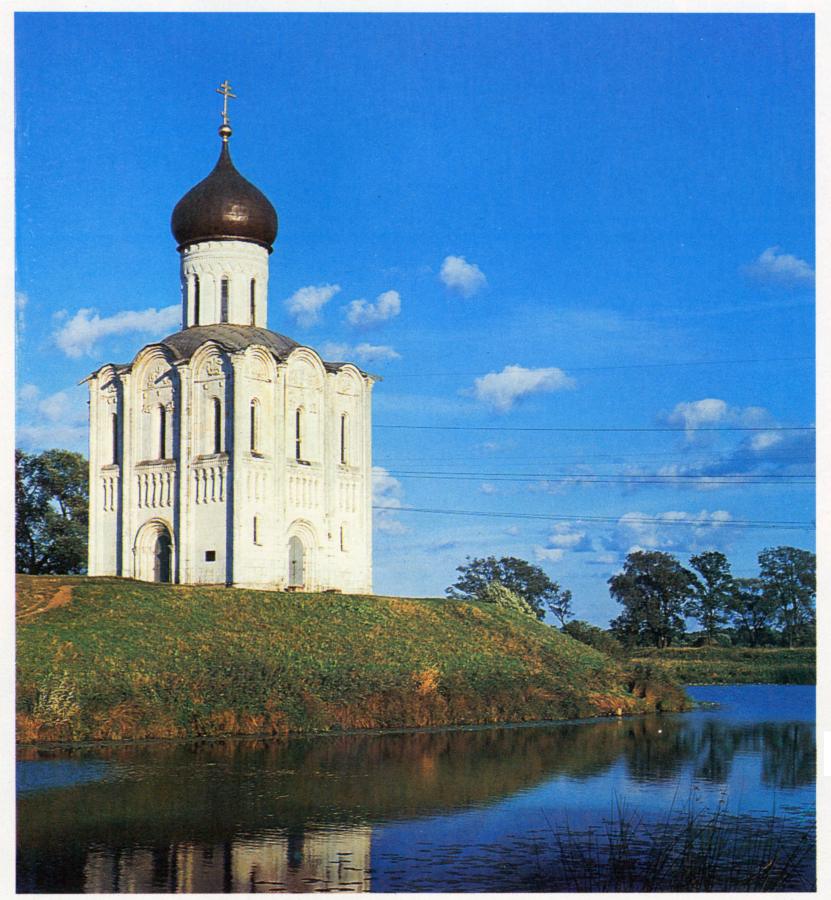

The Epistle of Presbyter Johannes might be referring to the famous Russian Church of Holy Auspices on River Nerl, near Vladimir. Nerl is a tributary of the Klyazma, which flows into the Volga. Incidentally, River Teza, or Physon, which we have already mentioned, is also quite near. The construction of the Church of Holy Auspices on River Nerl is dated to 1165, or the alleged XII century. This ancient Russian church has a distinctive characteristic of getting completely cut off by floodwater every year, photographed by countless tourists, understandably impressed by the sight of a white church standing amidst the waters (see figs. 8.12 and 8.13).

Why does the Epistle of Presbyter Johannes mention St. Thomas and an eight-day period alongside the floods? The reason is simple – the floods usually end in the springtime, right after Easter, and the Russian Church celebrates the Holy Feast of St. Thomas on the eighth day after Easter, which is when it can be approached again. The literary work known as the Epistle of Presbyter Johannes appears to reflect an actual historical fact. We naturally don’t claim the church described in the letter to be the Holy Auspices of the Nerl; the important thing is that the custom of building such “floodland churches” did exist in the ancient Vladimir and Suzdal Russia.

Another possible repercussion of this tradition is the famous legend of Kitezh City, which is said to have submerged completely when the Tartars invaded. This is supposed to have happened in the “land of Yaroslavl”: “Georgiy Vsevolodovich departed to the Land of Yaroslavl, where the two cities of the Greater and Lesser Kitezh had stood. This is also the location of the battlefield where the Russians were defeated” ([634], page 561). According to the legend, the churches of this “underwater city” haven’t ever stopped the liturgy for a second ([634]).

It is highly remarkable that the Epistle of Johannes dates from the very same epoch of the “Tartar” invasion, which is also the epoch of “floodland churches”.

We could have agreed with historians about the alleged pointlessness of taking such fable-like accounts taken from the Epistle of Johannes seriously. Indeed, this document is exceptionally vague and inconsistent – yet our research demonstrates that such evidence should by no means be written off as nonsense a priori. The Epistle is a good example of how the reality of the XIV-XVI century underwent mysterious permutations in the literary works of the XVI-XVIII century. There is nothing extraordinary about this fact – later authors or editors were often forced to write about phenomena that they did not understand, and so the texts became filled with the scribes’ own inventions in accordance with whatever their lineage and education dictated. However, the key words were usually left intact (such as St. Thomas, eight days, a church amidst the waters in the present case).

It is hardly surprising that J. K. Wright, a modern historian, feel some sort of unease when he has to deal with the mediaeval “legend of Presbyter Johannes”, so this is what he says: “We had every reason to reject the report concerning the visit paid to the Romans by Patriarch Johannes”. This is why he comments as follows: “We would have every reason to reject the story about Patriarch Johannes visiting Rome as thoroughly outlandish if it weren’t confirmed in a letter sent to a certain Count Thomas by Abbot Audot from the Friary of St. Remy in Rheims (1118-1151), whose visit to Rome coincided with that of Johannes.

One shouldn’t immediately draw parallels between Patriarch Johannes, the guest of the Romans hailing from a distant land, and the actual ruler of the Empire, or Presbyter Johannes, also known as Ivan Kalita, the Great Khan; the former must have been an envoy of the latter, immortalised in the halo of his liege’s glory.

And so we see yet another coincidence between the Empire of the Horde and the Empire of the Horde. The identification of Edon as the modern Ganges or Hindus is a rather late theory, introduced in the epoch when the Scaligerian version became official and the old meanings of names were befallen by oblivion.

6.6. The identity and location of the ancient India.

The issue formulated in the name of the section is anything but self-implied. Mediaeval authors “were using this name for referring to every remote part of Asia” ([722], page 244). The term was extremely vague and could refer to a vast number of territories. From the Western European viewpoint of the XIII-XVI century, nearly all of Asia had somehow pertained to India, mysterious and distant.

It turns out that “India” is an ancient Russian word, derived from the now obsolete word “inde”, standing for “elsewhere”, “from the other side”, “somewhere” etc ([786], page 235). Therefore, the name “India” is really a generic way of referring to a foreign land. The Russian word “inde” was then borrowed by the creators of Latin in the XV-XVI century, without so much as changing a single sound – according to the modern Latin dictionaries, “inde – thenceforth, from that place” ([237], page 513).

A while later, West Europeans started to use the word simply as a synonym of a “faraway land”, hence the word “India”. Thus, a passage about India contained in the book of some mediaeval author from the West of Europe does not necessarily apply to the modern India – in particular, it was used for referring to the distant mediaeval Russia, or the Horde.

Next, the geographers of the Middle Ages divided India into three parts. The first India was indicated as the opposite of Ethiopia, for some reason. The second was the neighbour of Mydia – possibly, Hungary (also known as the Magyar Kingdom). The third India was reported to have been located at the very edge of the world ([722], page 244). Actually, the word “Mydia” might stand for “the land in the middle”, or “midland”.

Our reconstruction confirms the correctness of this division – the mediaeval Horde Russia has indeed always been divided in three parts, as we mention it in CHRON4: Greater Russia, Lesser Russia and White Russia (also known as the Golden Horde, the Blue Horde and the White Horde, respectively).

Actually, the letter of Epistle Johannes claims that he was the ruler of “the three Indias”. It also turns out that there were three Apostles preaching there – Thomas, Matthew and Bartholomew (in the Lower, Central and Upper India, respectively, according to [722], page 244).

6.7. What the West Europeans of the XII-XVI century knew about India.

We must abandon the thought that the mediaeval West European geographical conceptions of the XIII-XVI century were more or less close to their modern counterparts. This is extremely far from the truth – said conceptions are most likely to be of a figmental nature. It is the very dawn of geography as a science, which had only accumulated enough correct empirical observations by the XVII-XVIII century. As for the chronicles of the XIII-XVI century, they usually mention India in the same vein as the following excellent resume compiled by Wright from the mediaeval “Geographies”. It absolutely deserves to be published separately.

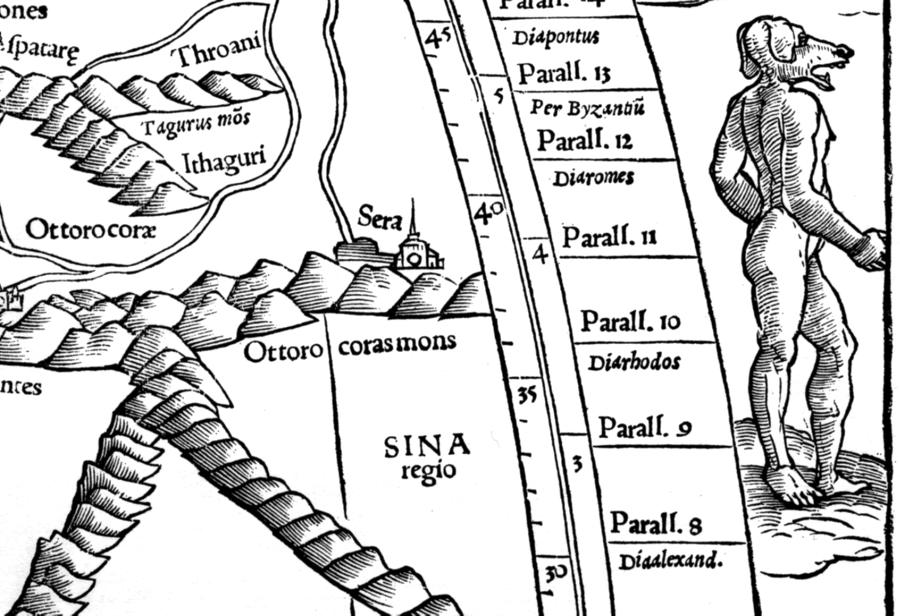

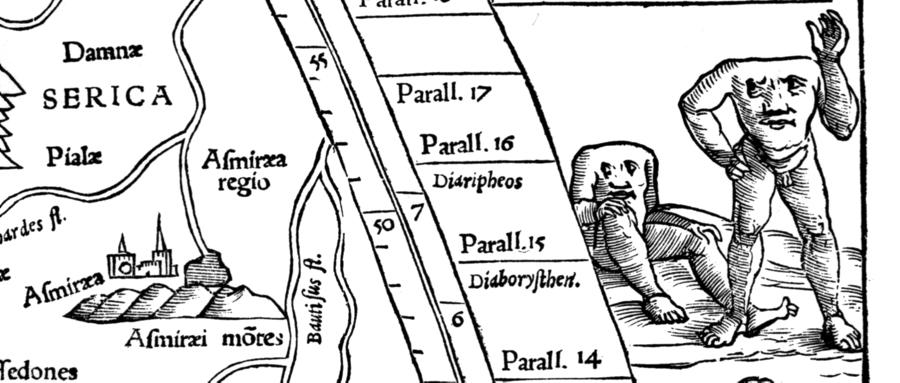

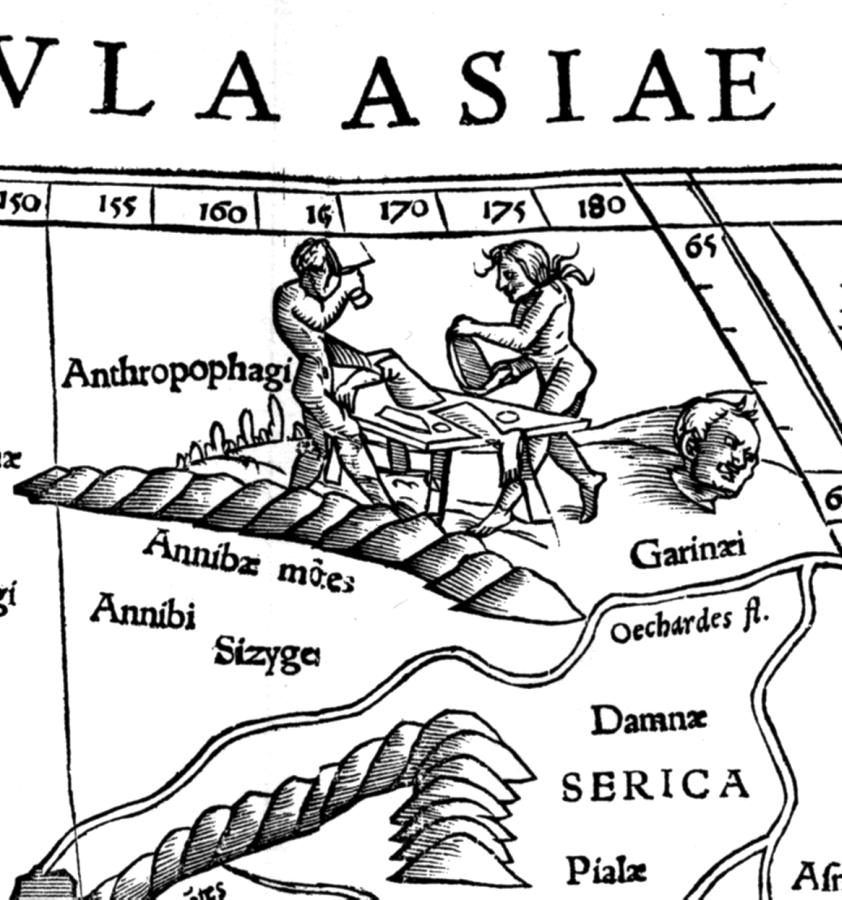

According to J. K. Wright, “first and foremost, India was a wonderland, inhabited by pygmies who battled against cranes and giants who fought griffins [we are citing a fragment of a map compiled by the “ancient” Ptolemy, allegedly published in 1540 – see fig. 8.14 – Auth.].

Other inhabitants included the “hymnosophists” who spent the whole day observing the sun, standing in the blistering heat on one foot first, and then on the other.

There were people with eight-toed feet facing backwards.

The Cynocephali, or the people with canine heads and claws, barking and growling [see fig. 8.15 – Auth].

A nation whose women always give birth to just a single child, who is always white-haired [see fig. 8.16 – Auth.].

A people whose hair is white in the days of youth and get darker with age.

People who sleep on their backs and hold their only foot of an enormous side above them to find shade, or the so-called sciapodes [see fig. 8.17 – Auth.].

People who satiate themselves with nothing but the smell of food.

Headless people whose eyes are inside their stomachs [see fig. 8.18 – Auth.].

Forest people with hairy bodies, canine fangs and intimidating voices, as well as a whole variety of terrifying zoomorphic monsters that combine the features of several animals at once.

These, and even greater wonders, were what the European authors of the crusade epoch kept telling us about” ([722], page 248).

We see an awkward mixture of realities – local customs misunderstood by foreigners, accompanied by misinterpreted and mistranslated names and terms, which have spawned ludicrous fantasy notions. Such was the level of geographical knowledge of the West Europeans in the Crusade epoch insofar as Asia, Russia (or the Horde) and the Orient in general were concerned.

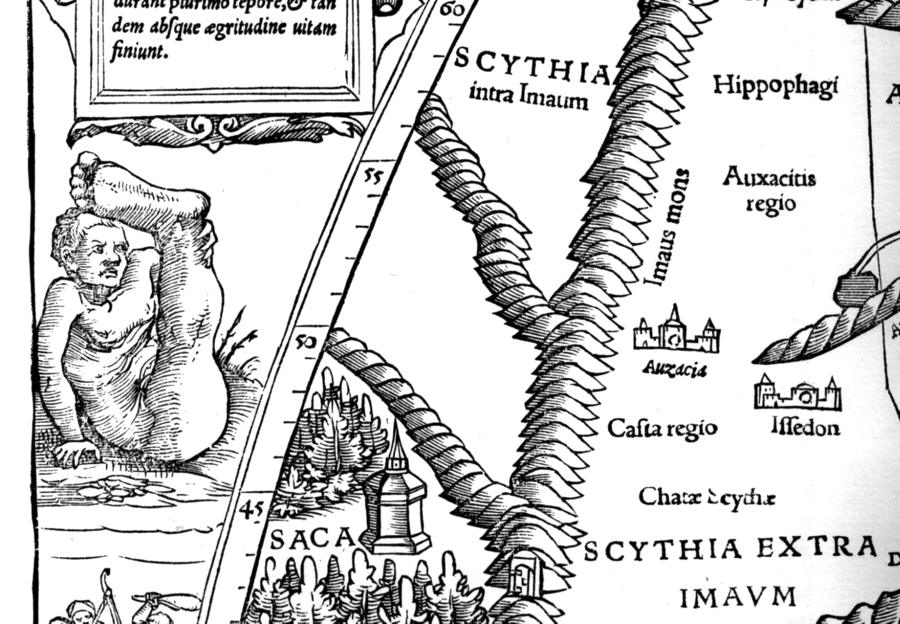

We shall conclude with another map fragment taken from the “ancient” Ptolemy’s Geography, first published in an edition of S. Munster allegedly dating from 1540 (see fig. 8.19). The everyday life of the Scythian cannibals is represented most explicitly indeed – the Tartars, or Scythians, are busy cooking a rather unsophisticated meal, carving the corpse of either an enemy or a compatriot. This is how the West Europeans started to portray the ancestors of the modern Russians around the epoch of the Reformation and later; alternatively, this might be a distorted perception of some misunderstood custom.