Chapter 12.

Western Europe of the XIV-XVI century as part of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire.

5. Futile attempts of the Westerners to drive a wedge between the allied forces of the ancient Russia and the Ottoman = Ataman Turks.

“The part that Russia plays in the life of Europe is drastically altered as a result of the unification of Russian lands and the creation of a centralised Russian state. Russia’s strength in the second half of the XV century instantly became an important factor in the international life of Europe” ([344], page 68). Also: “the strength of the ‘Muscovite’ was discussed persistently at European courts and described in European press” ([344], page 167).

Everything is correct – yet we must also add the XIV and the XVI century, when Russia was still dominating the historical arena as the Great = “Mongolian” Empire.

Western Europe of that day and age was doing everything in order to stop the “Mongol”, or Turkish (Ataman) conquest and sign a peace treaty. Such a treaty was signed between Russia and (presumably) the Habsburgs as late as in 1514 ([344], page 69). We must make the important notice that, according to our reconstruction, the Habsburgs of the XIV-XVI century identify as the Novgorod rulers of Russia, or the Horde, the Czars (Khans) regnant in the “Mongolian” Empire. The Western European rulers only claimed the “Habsburg” title as their very own in the XVII century, after the Reformation. They took the former “Horde” history of the Novgorod rulers as a bonus. Therefore, the only “treaties” Russia, or the Horde, could have signed with anyone in the Western Europe would involve its own vicegerents appointed in the Western Europe by the Great Czar, or Khan.

“To make Russia participate in the military action against Turkey becomes the primary goal of the Habsburg diplomats. Rome harboured similar plans. Popes Alexander XI, Leo X and Clemens VII repeatedly addressed the Great Prince of Moscow urging him to join the war with the Turks.

Rome also dreamt of uniting the Occidental Catholic Church with its Russian Orthodox counterpart, which it hasn’t managed to do with the aid of the Florentine union” ([344], page 69). It is most likely that the author is referring to the XVII century and not the XVI. The true meaning of the authentic events becomes more or less obvious from this recent rendition of the ancient documents by the Romanovian historians.

The Western Europe of the later XVI strove to fragment the Great = “Mongolian” Empire. However, this remained an impossibility while the “Mongolian” Khans, or the Great Princes, remained regnant in Russia. Indeed, it would be odd to expect the Khan, or Great Prince, to set out against his own Horde, or the Cossack army led by the Atamans (Ottomans).

Indeed, the distorting prism of Romanovian history still conveys some of the epoch’s events in a recognizable manner. “The plans of ecclesiastical union were decisively rejected by the Russian government, which had also evaded joining the anti-Turkish league, founded as a joint initiative of the Empire [reputedly, the Habsburgs – Auth.] and Rome” ([344], page 70).

In the alleged XV (and, most probably, in the XVI) century the Western Europe is desperate to find a way to “the heart of Russia” so as to drive away the Eastern menace. One of such attempts was as follows: “In 1489 imperial envoys appeared in Moscow [presumably sent by the Habsburgs – the Occidental vicegerents of the “Mongolian” Empire in reality – Auth.] . . . with expressions of “love and affection” addressed at the Great Prince of Moscow, accompanied by the offer of the German crown and a project of marriages between German princes and the daughters of Ivan III. Although Ivan rejected the crown, he had sent envoys to the Emperor in return” ([344], page 74).

Let us add the following: the Great = “Mongolian” Prince, or Khan, is unlikely to have been tempted by the West European “royal crown” of his own vicegerent. The Western Europe was compliant and punctual with tribute payments to the Cossack Atamans at any rate – very punctual indeed, as we have seen above, in order to avoid the fury of the Oriental rulers.

Let us also point out the understandable “desire of the Roman King Maximilian to enter a union with the Great Prince of Moscow” ([344], page 75).

In the alleged first half of the XVI century (in reality, this must have taken place in the XVII century) the “Turkish issue” became “the focal point of the talks between the West European rulers and Russia. In order to influence Russia and urge it towards military action against Turkey, the Habsburg diplomats were emphasising the great scale of the Turkish menace” ([344], page 82). All the urges were futile. The Great = “Mongolian” Khan and his Cossack Atamans were constituting a single Imperial body back in the day, which is obvious even through the distorting prism of Romanovian history.

“For a long time, Russia wasn’t menaced by the Turks in any which way. Therefore, the diplomatic relations between Russia and Turkey established near the end of the XV century [much earlier than that according to the New Chronology – Auth.] remained amicable up until 1569” ([344], page 146). The second half of the XVI century, that is. Everything is perfectly correct – this is precisely what our reconstruction claims, qv in CHRON4.

6. How the Western Europe finally succeeded in making Russia and Turkey hostile towards each other.

We have formulated our hypothesis many a time already; let us merely sum up in brief.

1) The lengthy attempts of the Western diplomats finally proved successful in the late XVI – early XVII century. The Great Strife provided the ability to support the pro-Western Romanovs in their endeavours to seize the Russian throne. The operation was a success (see CHRON6 for more details).

2) The Horde loses. The Romanovs devise new and radically different governing policies.

3) The commencement of the senseless wars between Russia and Turkey. The Western Europe gets a chance to draw a breath.

4) Peter the Great opens his “gateway to Europe”, striving to introduce the Western specimens all across Russia, which becomes occupied by foreigners to a great extent.

5) The tendentious recreation of Russian history begins, with a purpose of making it correspond to the needs of the Romanovs.

6) The Western European historians are very happy about these activities, especially considering the recent release of their version of the “extremely long ancient European history”. The surviving mediaeval documents were covered by a thick layer of Scaligerian history. Contradictory data were either hushed up or transplanted into distant past and ascribed to other lands and nations (alternatively, mercilessly destroyed). Old books burn well, after all. The index of forbidden books is introduced, with their possession punishable by live incineration.

7. The joy of liberty.

Western Europe got a chance of drawing a breath in the XVII century, and started to kick the weakened lion – with much timidity initially, and ever braver.

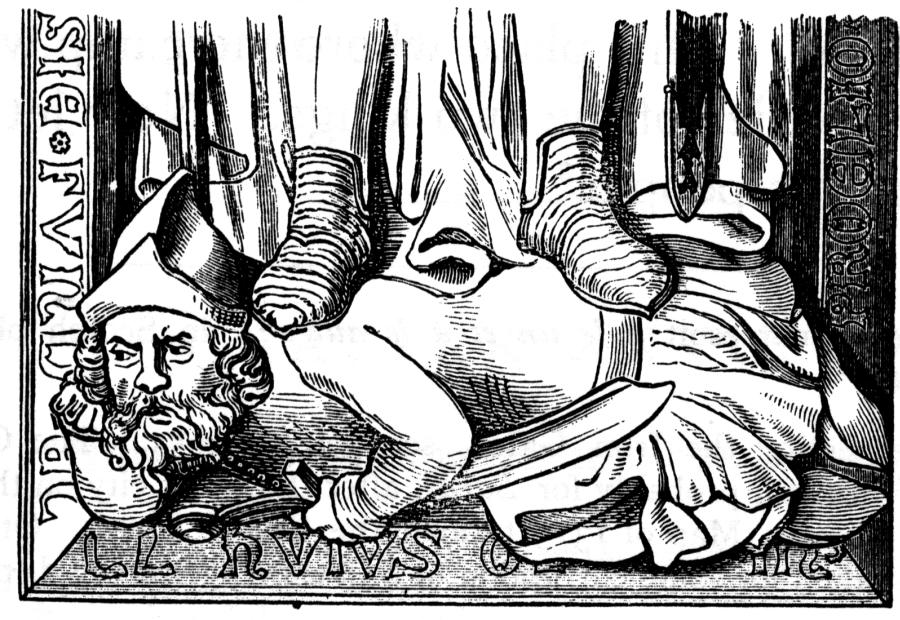

A good example is as follows. In fig. 12.4 the reader sees a curious ancient piece of artwork from the sepulchre of Duke Heinrich II. This is what the read in the legend right underneath: “A figure of a Tartar under the feet of Heinrich II, Duke of Silesia, Krakow and Poland, placed on the grave of this duke in Breslau upon his demise in a battle with the Tartars at Liegnitz on 9 April 1241” ([1264], Volume 2, page 493).

Just a second. Who killed whom? Did the Tartars kill the Duke, or vice versa? If the former is the case, why does the duke have a dead Tartar under his feet if the reverse would be closer to reality?

The artwork is most likely to date from a much later epoch – the XVII century the earliest. It is a psychological means of revenge. When the Russian “Tartars” could be feared less, artwork of this sort started to appear on the graves of the defeated Western rulers. A propos, why does the Tartar on this picture have a Russian face, a long beard, a Russian scimitar and the well familiar hat of a Russian marksman?

The English word “slave” must also be derived hence, since there are also older terms in existence, such as “bondman”, “bondwoman”, “bondmaid” etc. Similarly, the Latin “servus” is likely to be derived from the name “Serb”.

As an example of how the Westerners started to describe Russia in the XVII-XVIII century we shall quote a few passages from the works of Kasimir Waliszewski, a Polish historian quite popular nowadays, and believed to be of an almost academic credibility as a source: “He published a whole series of books about the Russian kings and emperors in France, starting with 1892” ([119], page 4).

K. Waliszewski: “The formation of the kernel that consisted of refined and elegant people interested in intellectual issues occurred early at the French court, and the entire French culture became enlightened as a result.

Nothing of the sort has ever existed here [in Russia – Auth.] . . . No knighthood has ever existed, and the finer details of fencing remain unknown . . . Disputes were settled instantly, with a strike of a fist – with blood gashing out, and a body falling down with a hoarse breath . . . Such a long way from Versailles. These courtiers, fighting like grooms, are nevertheless dressed as royalties . . . One of the churches . . . “behind a golden grill” was even ascribed the role of a “Cathedral”. The grill was naturally gilded and not really golden . . .

In the large hall, the royal throne had two lions, each on either side, which were outfitted with an ingenuous mechanism that made them roar . . . Reutenfels claims that . . . they looked quite amusing, like a toy, but Simeon of Polotsk classifies them as the eighth wonder of the world in some poor quality verse. Also a far cry from Versailles” ([119], pages 354-356).

K. Waliszewski didn’t find it hard to come up with similar passages from the works of West Europeans that were published in the XVII-XVIII century. The joy of liberation is obvious from a great many passages. Streuss, for instance, wrote the following in 1669: “Muscovites have a rough, beastly outlook . . . This nation was born for slavery . . . They are so lazy by their very nature that they only work when they have no other option . . . Like every filthy little soul, all they really love is slavery . . . They willingly steal everything they can lay their hand on . . . They are exceptionally uncouth, wild and ignorant, treacherous, aggressive and cruel” ([119], page 314).

Perry in 1696 happily agrees: “In order to find out whether a Russian is honest, one must see whether he has any hair on his palms. If he has none, he is definitely a swindler” ([119], page 315).

“Kryzanic attended a banquet there, and observed that his ware had not been washed for a year at least [one wonders how he managed to give this precise an estimate – Auth.]” ([119], page 318).

K. Waliszewski authoritatively concludes: “The picture we get when we consider all the evidence presented above, which is unanimous and precludes us from errata, is one of utter repulsiveness” ([119], page 318).

We see the very nascence of the myth about Russia’s inferiority – a myth that is still alive, despite its unveracious and artificial nature. Yet this myth characterises the atmosphere when the final version of Russian history was created by Miller, Bayer, Schlezer and their ilk.

8. Mediaeval Russian accounts of the Western Europe.

8.1. In re the XV century Rome in Italy.

According to our reconstruction, Rome in Italy was only founded at the end of the XIV century. Even if there was some minor settlement on this site previously, it hadn’t been the capital of anything at all.

And so, “a small but curious note appears in handwritten compilations of the XVI-XIX century . . . It contains the very first description of Rome known in Russian literature . . . One notes the author’s observation that Rome was deserted” ([344], pages 52-53).

Everything is perfectly correct from the viewpoint of the New Chronology. However, Scaligerites would find this unbecoming, given Rome’s status of “the world’s capital”.

This is why N. A. Kazakova feels obliged to explain this oddity to the reader. This is what she tells us: “Rome was indeed undergoing a phase of decline in the XIV – early XV century: the economy was stagnant, the population diminished at a catastrophic rate, the buildings were becoming dilapidated and fell apart. Rome was a pitiful sight in comparison with Florence and Ferrara, and the Russian traveller pointed this out correctly” ([344], page 53).

However, we shouldn’t get the idea that the ancient evidence in question did actually reach us the way it was recorded in the XIV-XV century. Apparently, “the note on Rome was first published by . . . A. Vostokov after a XIX century copy. The second edition was based on the original of the early XVI century . . . and made by V. Malinin” ([344], page 53). We are likely to be dealing with a late edition, which did nonetheless preserve some of the original’s features, and makes it obvious that Rome in that epoch looked nothing like the “capital of the world” due to desolation etc.

The corollary is as follows. The Russian traveller of the XIV-XV century who wrote the “Roman note” describes Rome exactly the way it should have been back in the day – void of any luxurious “ancient” buildings and temples believed to be “integral parts of the ancient Rome in Italy” nowadays. All of them were built somewhat later – in the XVI or the XVII century (possibly, even the XVIII).

8.2. On the life of the Western countries in general.

The Russian author of “A Voyage to Florence” writes a substantial deal about the European countries that he had seen.

How does he characterise those countries? “The author of the ‘Voyage’ is very respectful in reference to the culture and the life of the Western countries, although occasionally also naïve in his admiration of the Western culture and technology. He doesn’t demonstrate any hostility towards the West, although the countries he visits are Catholic” ([344], page 42).

We are by no means trying to imply that the Easterners were respectful when they wrote about the West, and that the Westerners only wrote about the East irreverently and derisively. There were more than enough statements of every kind from either part. In the present case we would like to voice the following hypothesis. It could be that Catholicism was still close enough to Orthodox Christianity, which would give no reasons for a religious opposition. The schism begins with the failure of the Ferraran and Florentine Union in the XV century and not in the XI, as Scaligerian chronology is trying to convince us. Apparently, differences between various Christian confessions came to existence in the XVI-XVII century and not any earlier.

8.3. The attitude to the Bible in the Western Europe.

Today we believe that the Bible in the mediaeval Western Europe was treated in pretty much the same manner as today – as a collection of holy texts treated with great reverence, whose public reading and discussion is only acceptable in the solemn atmosphere of a church, in solemn, ascetic and academic tones of a sermon.

Apparently, the original ancient tradition of church service was precisely in this vein – the one introduced in Byzantium in the XII century. This moderate service tradition was inherited by the Orthodox church and preserved until the present day (the word “Orthodox” might be derived from “Orda-Dukh”, roughly translating as “The Horde’s Faith”).

The moderate Islamic service must be a close relation of the Orthodox tradition.

This ascetic form of ritual is also adhered to in the modern Catholic West.

However, Christianity hasn’t always been ascetic and restrained in the Western Europe. As we mention in CHRON1, Chapter 7:3, the Bacchic cult of the Graeco-Roman Olympian pantheon known to us from the “ancient” Greek and Roman texts was the Western European mediaeval version of Christianity, initially an ascetic cult. CHRON1, Chapter 7 contains an extensive collection of materials that also mention the erotic sculptures in many Christian temples of the Western Europe – a vivid demonstration of how distant the mediaeval Christian tradition of these countries had been from the initial Christian cult of the XII century.

The reform of the Western Church that introduced the Inquisition must have been aimed at a return to the former ascetic tradition. Possibly, this was stipulated by such negative social aftermath of the orgiastic Bacchic tradition as the wide propagation of venereal diseases in some countries of the Western Europe.

N. A. Morozov also voiced a hypothesis that the Western European theatre has its roots in the ecclesiastic Christian performances with decorations and the like, very widespread in Europe during the epoch when this specific kind of Christianity was prevalent.

Let us consider what Russian travellers of the XV century wrote about this issue. It turns out that in the churches of Italian monasteries Biblical themes were often presented theatrically and called passion plays ([344], page 69).

“The Russian traveller gives a detailed account of the passion plays based upon two Evangelical stories, namely, Virgin Mary learning that she was soon to give birth to the Son of God, and the ascension of Christ to heaven.

Although the passion plays, which were the primary theatrical events of the mediaeval West, were based on Evangelical stories, the playwrights transformed them to some extent, fancying them into religious dramas” ([344], page 60).

It has to be emphasised that the plays were presented in churches, which confirms Morozov’s idea about European Christian service of the epoch being completely different from the modern. This is the very epoch when the Occidental Church gave birth to theatre – the XV-XVI century.

The Orthodox bishop “Avraamiy of Suzdal describes the ecclesiastic passion plays [which he saw in Florence in 1439 – Auth.] in sufficient detail – apart from a rendition of the scenario, he relates technical information concerning the length and the width of the stage, light and sound effects, as well as technical contraptions used for movements, quite sophisticated for that epoch” ([344], page 61). From the modern point of view, it is quite astonishing that all of this should happen in a church.

“The theatrical plays, which were seen by the Russians for the first time, impressed them deeply. Avraamiy of Suzdal writes about them without any prejudice at all, quite exhilarated, calling them a ‘beauteous and wondrous sight’” ([344], page 61).

Nevertheless, this direction of evolution was not chosen by the Orthodox Russia, likewise Islam, although in the XVI century it already started to gain a certain degree of independence from Christianity.

Distinct marks of the former Bacchic mediaeval European Christianity were left in the Catholic architecture and art, demonstrating freedom from many moral restrictions inherent in modern Christianity.

Among them – the use of musical instruments, such as organs, during religious service, which is absent from Orthodox Christianity, likewise the naked or partially naked sculptures in churches, also forbidden in Orthodox Christianity and Islam. One should also mention the emotional visual art, a great deal more temporal, used in lieu of the strict icons. Mediaeval Western European artists rendered religious themes with a much greater degree of liberty than their Orthodox counterparts who painted the much more restrained icons.

Let us once again remind the reader of the explicit sculptures in the “ancient” tradition found in some mediaeval cathedrals of Europe ([544], also CHRON1, Chapter 7). The Passions of Christ (1152-1185) and the saints were painted in a very naturalistic manner, with unsettling physiological details such as bleeding open wounds, bodies pierced by torturers etc.

This ideology was particularly manifest in the sombre works of Bosch and many other Western artists of that epoch – the passionate paintings of heaven and hell, demons and so on. These paintings of Bosch and his colleagues were ecclesiastical art – not secular.

When we point out such differences, we are by no means trying to say that one brand of Christianity is better than another. Our mission is to point out the serious discrepancies between the nascent movements in Christianity, which eventually led to opposition in the XVII century. We believe that the understanding of such discrepancies is useful for the reconstruction of a more authentic version of the XIV-XVIII century history. Any such attempt shall inevitably concern the psychology of the Middle Ages apart from chronology – art, behaviour inside and outside churches, popular likes and dislikes and so forth. This is the only way of understanding the nature of errors and distortions introduced by chronologists.

8.4. The global chronicle genre. The predecessors (or, rather, contemporaries) of Scaliger and Petavius.

We have already mentioned the fact that Scaliger and Petavius have created the skeleton of the erroneous global chronology in the XVI-XVII century, making it look more or less complete. Later historians of the XVIII-XX century merely complemented it with flesh and made it look more academic. However, neither the foundation of this edifice, nor its architecture drew any criticisms from their part – for obvious reasons. The sheer bulk of materials accumulated since the XVIII century was so great, and the respect for the authority of the first chronologists so strong, that nobody wanted to lay down their life for the search of possible errata with the imperfect means offered by historical science of the epoch. Natural scientific methods, including the ones based on mathematical statistics, were still absent from historical chronology.

One must admit that the very source of the erroneous chronology must predate the epoch of Scaliger and Petavius to a small extent. We claim that the historical materials of the XI-XVI century, correct and authentic for the most part, were erroneously organised and placed on the chronological time axis in the XVI-XVII century.

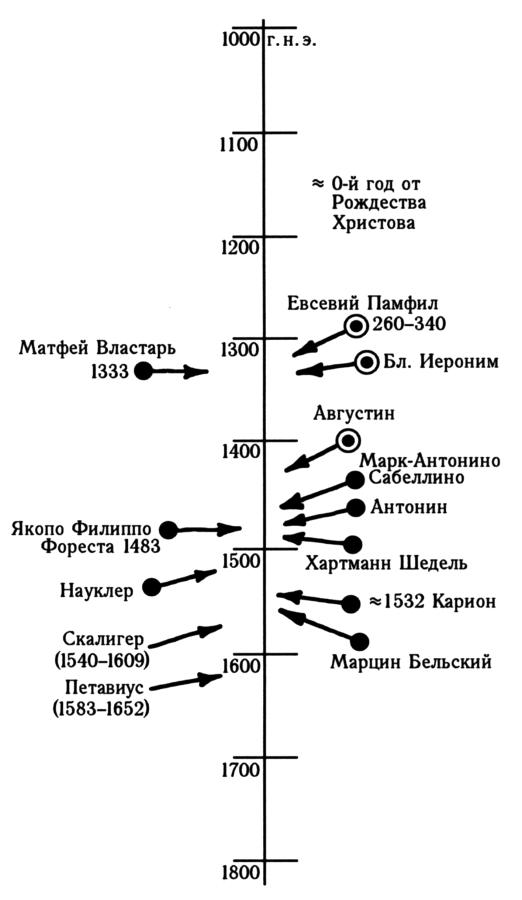

It would be interesting to find out who was the first to choose the wrong direction. It is naturally very difficult to estimate today. Let us however try. We shall mark the Scaligerian dates corresponding to the publications of the so-called “Global Chronicles” on the time axis. These are the very chronicles that served as the foundation of the edifice of global chronology in general.

It is believed that the actual “genre of global chronicles has evolved in the Western Europe [sic! – Auth.] . . . Around the same time, two high-ranking clerics, Eusebius Pamphylus, Bishop of Caesarea (around 260-340) and his junior contemporary, St. Gerome, created the basic periodic distinction in global history, followed by Augustine, Bishop of Ippon (V century)” ([344], page 229).

Since all the ecclesiastical authorities mentioned above lived in the epoch of the Roman Empire of the alleged III-VI century, their lifetime needs to be moved forward in time according to the New Chronology – by a factor of 1000, 1053 or 1100 years. As a result, it shall fall over the XIV-XV century A. D., qv in fig. 12.5; possibly – the XVI-XVIII century, if the chronological shift was greater.

Seeing as how historians themselves credit these characters with the creation of the global chronology in its first rough version (as a “periodic distinction”), we are brought to the following important hypothesis. The first rough schemes of the global history were created in the XV-XVI century the earliest courtesy of Eusebius, Jerome and Augustine.

Moreover, the schemes as they have reached our day and age were drawn up within the Roman Catholic Church of the XVII-XVIII century. This is yet another proof of our idea that the budding schism between the churches of the XVI century could have been the incentive for the creation of an artificially extended global chronology in the XVII century Western Europe in order to lend more authority to the freshly introduced Latin Catholicism, a successor to the Orthodox Church.

The chronological research reflected in the book of Matthew Vlastar is also dated to the alleged XIV century. His work and his errors were studied by G. V. Nosovskiy and related in depth in CHRON6.

“In the late XV – early XVI century, the tradition of compiling global chronicles still existed in Germany and in Italy. The XV century Italian humanists . . . were usually concerned with local and national affairs, hardly ever delving into global history [? – Auth.]” ([344], page 229).

A global chronicle was written by Archbishop Antoninus of Florence (died in 1459). However, it was only “published post mortem – in the 1480’s” ([344], page 229).

“The periodical division of history into six epochs, traditional for the mediaeval historical thought, was also preserved by Jacobus Philippus Foresta of Bergamo, whose oeuvre came out in 1483. As for the Italian humanists, the one involved in the research of global history is Marcus Antoninus Sabellicus” ([344], page 229).

Around the end of the XV century, global chronicles came to Germany. We are referring to the chronicle of Hartmann Schedel, and the ensuing Chronicle of Naucler, the Swabian historian, which covers the period until 1501 ([344], page 230). Incidentally, historians themselves recognise that Naucler “wasn’t critical in his use of his predecessors’ works” ([344], page 230).

Another global chronicle known to us was written by Carion, an apprentice of Melanchton; it ends with 1532 ([344], page 230).

In 1551 the “Global Chronicle” of Marcin Belski, a Polish writer and historian of circa 1495-1575 came out.

It is believed that “Russian literature of the second half of the XVI century knows of just a single translated source with materials concerning the Western Europe – the ‘Global Chronicle’ of Marcin Belski” ([344], page 227).

It also turns out that “the primary source used by Marcin Belski was the global chronicle of Naucler” ([344], page 233). It is curious that the work of Marcin Belski “was introduced in the list of works banned by the Catholic church when the counter-reformation came to power in Poland” ([344], page 234).

Finally, in the XVI-XVII century Scaliger and Petavius write their works, concluding the construction of the erroneous ancient chronology. However, let us reiterate that all the abovementioned chronologists also lived in the epoch of the XVII-XVIII century. This will make them contemporaries or even followers of Scaliger and Petavius and not predecessors.