Chapter 12.

Western Europe of the XIV-XVI century as part of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire.

11. The identity of St. George.

11.1 The Russian cult of St. George the Victorious.

In the beginning of the XIV century, Great Prince, or Khan Georgiy = Youri Danilovich ascends to the Russian throne. He was also known as Genghis-Khan, qv in CHRON4, Ryurik of the Russian chronicles, the founder of Russia (see CHRON4), Mstislav the Valiant, brother and co-ruler of Yaroslav the Wise in the alleged XI century (see CHRON4), and Georgiy Vsevolodovich in the alleged XIII century (see CHRON4).

To sum up, the character in question was the founder of the “Mongolian” Empire, also known as Russia, or the Horde. A famous relation of his was known as Ivan Kalita, or Caliph, and also as Batu-Khan, or Yaroslav the Wise.

Georgiy, or Genghis-Khan, the founder of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire left a deep and irremovable mark in world history.

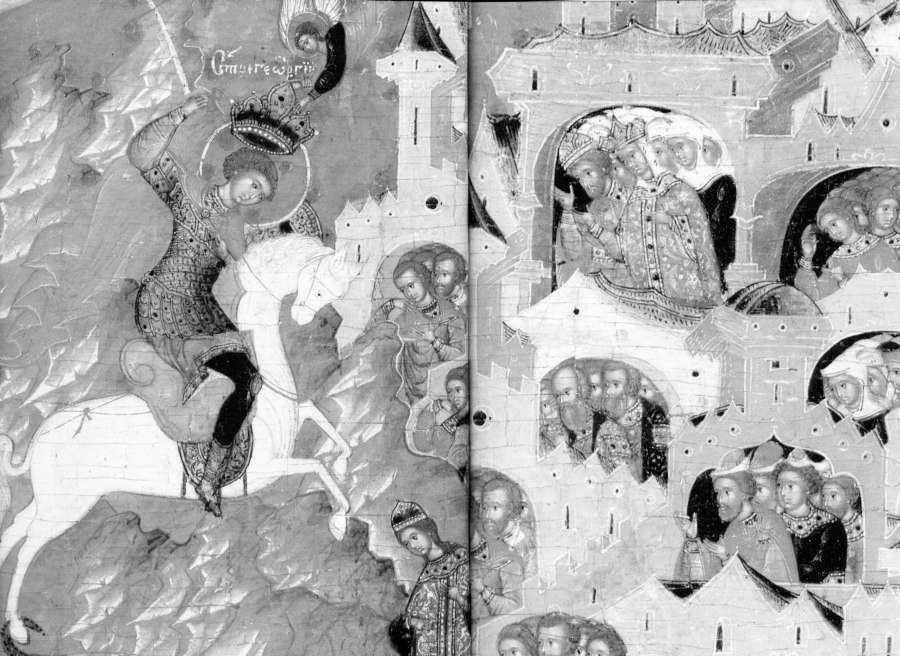

The Scaligerian and Romanovian history does not dispute it. However, our reconstruction demonstrates that the memory of Georgiy, or Genghis-Khan, is preserved by much wider and deeper layers of world history than we have previously thought. The memory of this historical figure was kept alive throughout the whole Great = “Mongolian” Empire, including the lands that were under its influence at some point. We are of the opinion that this historical figure of the XIV century is directly related to the foundation of the cult of St. George the Victorious, which would later become universal. In fig. 12.15 we reproduce one of the most famous Russian icons of the XIV-XV century depicting St. George the Victorious.

This is what the encyclopaedia entitled “Christianity” has to tell us: “St. George the Victorious – a saint, a great martyr and one of the most popular saints, the main character of many legends and songs of every Christian nation as well as the Muslims . . . This figure [St. George – Auth.] must hail from Syria and Palestine” ([936], page 406).

What is the ancient Syria? Apparently, in some of the chronicles Syria, Assyria and Ashur are reverse readings of the name Russia. As we can see, the Christian tradition is correct to associate St. George with Russia, or Assyria. Let us remind the reader that the name of the modern Syria came from Russia, or the Horde, and was brought to Syria in the Middle East during the Great = “Mongolian” conquest.

The encyclopaedia continues: “According to the legends of Metaphrastes, St. George hailed from a distinguished Cappadocian family and held a high rank in the army” ([936], page 406). This is correct – he was the leader of the entire army of the Horde. Genghis-Khan’s rank was the highest.

Further on Christian tradition informs us that St. George later “laid down his military rank and became a confessor of Christianity” ([936], page 407). This is the presumed reason why he was decapitated and canonised as a Christian martyr. Since the Horde, as well as its rulers, including Georgiy, or Youri, adhered to Orthodox Christianity and exported it to the conquered territories, it is obvious enough why the cult of St. George the Victorious should be supported by the Christian Church the most.

It is possible that St. George, whose Christian name was given to Genghis-Khan at baptism, was already known in the XIII-XIV century – however, the magnitude of Genghis-Khan’s personality served as the primary source of materials for the new cult of St. George the Victorious. Even the way in which St. George was portrayed on the icons changed in the XIV century – all of a sudden, everybody started to paint him upon a horse, wielding a spear. This is very idiosyncratic indeed and completely untypical for any other Christian saints. It is however known that the initial ancient representations of St. George were of a more customary nature. Moreover, in some of them we see angels laying a royal crown upon the head of St. George (see figs. 12.16, 12.17, 12.18, 12.19 and 12.20). The suggestive title of “Victorious” must also owe its existence to the personality of Genghis-Khan, or the other George. The fact that St. George is also revered by the Muslims, qv above, is in excellent concurrence with our reconstruction, according to which Islam had not yet been independent from Orthodox Christianity in the XIV-XVI century.

“In our country [Russia – Auth.] his name has been given to the members of the Great Prince’s family ever since the dawn of Christianity: already in 988 A. D. [the real date is more likely to pertain to the XIV century – Auth.] Great Prince Yaroslav received the name of George during baptism” ([936], page 407).

Bear in mind that Yaroslav the Wise = Batu-Khan was a relation of George = Genghis-Khan who had also inherited his mission, the unification of Russia. Therefore, the fact that we encounter the name George (or Georgiy) in the “biography” of Yaroslav is perfectly normal.

“Yaroslav founded the monastery of St. George in Kiev, giving orders to ‘observe the holy feast of St George’ on 26 November all across Russia . . . After the victory over the Chud, Great Prince Yaroslav, or Georgiy [Batu-Khan = Ivan Kalita – Auth.] built the Church of Youri [or the Church of Georgiy = Youri = Gyurgiy = Ryurik – Auth.], which has subsequently been replaced by the Youriev Monastery. St. George is portrayed as a youth, a warrior upon a white horse slaying a dragon with his spear. Ever since Yaroslav [or Batu-Khan = Ivan Kalita – Auth.], artwork based on this theme could be found upon the seals and coins of the Russian Princes. In the epoch of Dmitriy Donskoi, St. George became the Patron Saint of Moscow” ([936], page 407).

“Ever since the XIV century [just like our reconstruction suggests – Auth.] the theme with a mounted warrior becomes the emblem of Moscow (subsequently part of the coat of arms of Moscow, and later also part of the National Coat of Arms of the Russian Empire)” ([533], Volume 1, page 275; see fig. 12.21).

“In the reign of Fyodor Ivanovich coins portraying St. George were given to warriors distinguished for valiance; it could be worn upon a sleeve or a hat” ([936], page 407).

It is for a good reason that the so-called “George’s Cross, or the Order of St. George, founded in 1769 in order to decorate officers and generals for valiance in battle” ([797], page 291) commanded such respect in Russia. See fig. 12.22.

Having distorted the history of the ancient Russia, the Romanovs could not have abolished the famous symbol of St. George. However, they have done their best to erase the memory of George as Ryurik and Genghis-Khan, ruler of the Horde.

11.2. The cult of St. George the Victorious in Europe and Asia.

The “Christianity” encyclopaedia also tells us the following: “In the West the worship of St. George and the churches devoted to this saint were introduced in the late V and also the VI century, attaining particular popularity in the epoch of the crusades” ([936], page 407). According to our new chronology, this epoch falls right over the XIV-XVI century, which is when the Russian and Tartar Empire of the Horde and the Atamans reached further West, bringing with it the cult of St. George.

“Richard Coeur de Lion believed in a special patronage of St. George. The English Order of the Garter, founded by Edward III, considers St. George its Patron Saint” ([936], page 407).

“Since times immemorial St. George has become a folk character to such an extent, that a local variation of his name can be found in every country: he was Jorge for mediaeval Germans, Georges for the French, Yegoriy or Youri for the Russians, Gergi for the Bulgarians, Khorkhe for the Serbs, Jerzy for the Polish, Jiry for the Chechs, Djerdjis for the Arabs etc. In some cases, St. George was revered under local names . . . for instance, the Ossetian Wastyrdzhy, or Khyzr (Keder) in the Muslim East. His holy feast is considered very important in every Slavic part” ([936], page 407).

The Christian hagiography of St. George “served as a source for the French and German poems, and became rather popular in the Muslim East. Its Russian renditions gave birth to the Russian holy poem of ‘Yegoriy the Brave’, wherein the saint acts as the founder of Russia itself” ([936], page 407). This is in good correspondence with the chronicle report of Ryurik = Georgiy, Founder of the Russian Land. See above and in CHRON4.

Another encyclopaedia ([533]) reports the following: “His refined aristocrat’s traits made George an exemplary figure to symbolise the honour of the nobility: military nobility in Byzantium, princes in Russia and knights in the Western Europe” ([533], Volume 1, page 274). In fig. 12.23 we see an ancient engraving that depicts St. George as a mediaeval knight in plate armour. The engraving was made by the famous artist Lucas Cranach in the alleged year 1506. As we realise today, such portraits of St. George, numerous as they are, have nothing to do with any allegories, as historians tell us. Most likely, during military campaigns St. George, or Genghis-Khan was indeed covered in plate armour from head to foot. He was often seen on a warhorse, and this is how he was depicted. Incidentally, “folk tradition ascribes the qualities of a legendary warrior to George: ‘Red sun upon his forehead and fair moon on the back of his head’” ([135], page 15). Could this folk saying be a reference to the Ottoman star and crescent symbol as found on Genghis-Khan’s helmet?

The spring feast of St. George was celebrated on 23 April. “A ritual grazing of the Sultan’s kings was scheduled for this day by the Court Regulation of the Ottoman Turkey” ([533], Volume 1, page 274). A motif of a “special relation between George and the horses” emerges eventually ([533], Volume 1, page 274).

We are of the opinion that the above reflects the memories of the mounted Cossack Horde led by George, a. k. a. Genghis-Khan.

11.3. George as the “ancient” warrior Perseus.

One of the most popular legends told about St. George concerns his battle with a dragon that was devastating a country, to whom its unfortunate inhabitants were forced to feed their children. “When the king’s daughter was brought forth to be eaten by the serpent, George appeared as a young warrior and pacified the snake” ([936], page 407). See figs. 12.24 and 12.25.

“This wonder was hugely popular in all the Christian countries, serving as a basis for many Greek songs, and generally famous in the Balkans and among the Slavs” ([936], page 407).

As we already mentioned in CHRON2, Chapter 4:1.2, the romantic “ancient Greek” myth of Perseus, a warrior riding a winged horse, who saved the beauty Andromeda from the horrible dragon, appears to be yet another version of this legend. Let us also remind the reader of our idea that the following famous themes are largely reflections of the legend of St. George, the killer of the dragon and the saviour of the princess.

The Biblical Tale of Adam and Eve (and the treacherous serpent), the “ancient” Greek Paris and Helen (or Venus), the “ancient” Perseus and Andromeda (and the serpent), and also the “ancient” Jason and Medea (and the serpent).

In fig. 12.26 we reproduce Raphael’s painting entitled “St. George the Dragon-Slayer”, allegedly dating from 1505 ([493:1], page 173). St. George is portrayed just like the “ancient” Perseus – namely, as a horseman with a sword killing a dragon. We see the saved princess in the distance.

Thus, the “ancient” Perseus must be another reflection of Genghis-Khan, the founder of the “Mongolian” Empire, also known as Great Prince Georgiy Danilovich of Moscow. All representations of Perseus and George follow a single pattern – the mounted warrior kills a monster, with a woman saved from the latter close nearby. The image of a mounted warrior must have served the purpose of emphasising the decisive role of the “Mongolian” cavalry in the army of Georgiy Danilovich = Genghis-Khan. The very name Perseus must be a derivative of P-Russ or B-Russ (White Russian). See CHRON2, Chapter 4:1.2 for more details.

11.4. The famous “ancient Greek” myth of the terrifying gorgon Medusa as a memory of the invasion of George’s Horde.

The well-known fable of the severed head of the terrible Medusa-Gorgon belongs to the "ancient" legends about Perseus.

Perseus cut off the head of Medusa and attached it to his shield. The head stayed alive, its single gaze of Gorgon-Medusa' turned every living thing into stone.

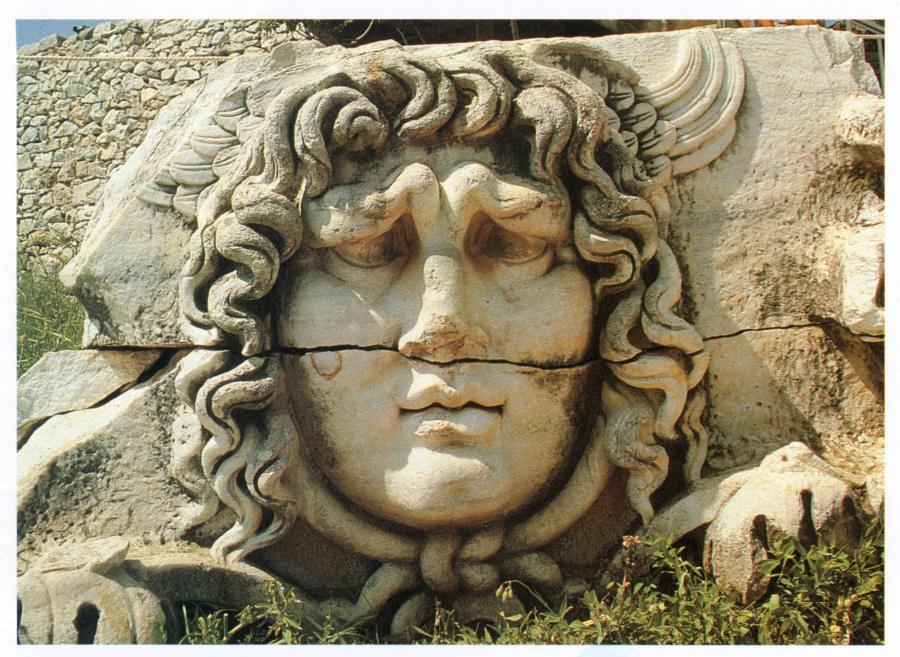

Numerous snakes twisted around her head, instead of hair. Fig.12.27.

In fig. 12.28 we see a famous painting of Caravaggio entitled “The Head of the Medusa” ([194], page 325; also [1255], page 16). The painting is presumed to date from between 1595 and 1597. It was painted specifically to decorate the Florentine arsenal as a ceremonial shield ([194], page 325). In other words, gorgon Medusa was still considered a military symbol at the end of the XVI century.

In fig. 12.29 we see one of the so-called megalithic “ancient” sculptures. It is the gigantic stone relief depicting the head of the Medusa from the temple of Apollo in the famous Turkish city of Dilima. In fig. 12.30 we see another Turkish stone relief with two heads of the gorgon Medusa – actually, the left head looks more male than female.

In fig. 12.31 we see an Etruscan sculpture of the gorgon Medusa’s head, and in fig. 12.32 – an Etruscan bronze coin depicting the head of the gorgon Medusa.

The numerous sinister legends of the gorgon Medusa must be reflecting the fear that the West Europeans had of the “Mongolian” armies of St. George, or Genghis-Khan. The very name “Gorgon”, or GRG unvocalized, might be derived from the name Georgiy, or Gyurgiy. It turns out that gorgon Medusa was one of the most important military symbols of the “ancient” Scythians. In fig. 12.33 we see a fragment of large Scythian bronze armour with the symbol of gorgon Medusa.

As for the snakes on the head of the gorgon, they are also a well familiar symbol. Snakes were decorating the headdress of the Pharaohs on the “ancient” Egyptian statues, qv in CHRON5 and CHRON7. This must have been an old symbol of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire. A trace of this symbol is recognizable in the Russian coat of arms as the heads of the bicephalous eagle, which are placed on top of unnaturally long necks and clearly resemble serpent heads (see CHRON7 for more details). Incidentally, the snake on the headdress of the Pharaohs was called Ureus – possibly, a derivative of the word Rus, Ra, the old name of the Volga, or ‘Ura’, the battle cry of the “Mongolian” army that is used by the Russian military until this day.

As a matter of fact, on the ancient engraving of Lucas Cranach that dates from the XVI century, the hair of St. George is so curly that it could be perceived as coiling serpents (see fig. 12.34). It is possible to reflect the vague memory of the “serpent hair” of the gorgon, or Genghis-Khan.

The artists of the XVI-XVII century must have already forgotten the initial meaning of the imperial symbolism – the bicephalous “Mongolian” eagles with serpent heads, and started to paint the horrifying image of the gorgon’s head surrounded by coiling serpents instead of hair. The image of the gorgon, or Georgiy, must have attained the features of a horror story for children in the XVII century, when the Reformist Western Europe seceded from the “Mongolian” Empire and started to perceive the great conquest of the XIV century, and, basically, its own past, in negative tones, sending it to faraway antiquity as the macabre image of gorgon Medusa.

It is curious that our theory about the name Georgiy being a possible precursor of the word “gorgon” finds a certain confirmation in the actual structure of the “ancient Greek” myth of the gorgons.

According to the encyclopaedia, “in Greek mythology, the gorgons are the monstrous offspring of the sea-god Phorcys and of Keto, the grand-daughter of Gaia, the Earth, and Pontus, the sea” ([533], Volume 1, pages 315-316). Apparently, after Greece was swept over by the Russian and Ottoman invasion of the XIV-XV century, some part of its frightened populace preserved the legends of the horrifying “George’s army”, or gorgons, unleashed upon them by George the conqueror.

The myth might be referring to the Gorgons (George’s army) as the offspring of PhRC = TRK (Turkey) and Keto; the latter is identifiable as China (Kitai), or Scythia, qv in Part 6 of the present book.

The “ancient” myth also contains a correct reference to Pontus, which is a name that was used the most often for referring to the Black Sea. The name of the goddess Gaia might reflect the well familiar GET = GOTH = GOG, or the Goths = Cossacks.

Let us reiterate that the surviving record of this veraciously ancient myth of the XIV century is most likely to date from a much later epoch, or the XVII-XVIII century, when the West Europeans already started to demagogically represent the “Mongol” invasion as frightening and monstrous. Such educational terminology also infiltrated the “ancient” myth of the Gorgons, or George’s Horde, according to our reconstruction. We are told that there were many gorgons, all of them extremely furious.

How about this passage: “The Gorgons . . . have a bloodcurdling appearance: winged and covered in scales, with snakes instead of hair, fanged, and with sight that turns every living thing to stone” ([533], Volume 1, page 316). We have already encountered such agitprop pathos in the book of Matthew of Paris, who gives a similar characteristics to the Slavic and Turkic inhabitants of the Great Empire, and countless other publications whose tone is just as hysterical.

11.5. Gorgon = George = Genghis-Khan represented in the symbolism of the “ancient” goddess Athena.

Even a fleeting familiarity with the “ancient Greek” mythology suffices to instantly notice another famous character with the same terrifying head of gorgon Medusa decorating her shield – Athena as a goddess of war, no less, who was born “in a complete battlefield outfit, uttering a battle-cry (Apollod. I 3, 6)” ([533], Volume 1, page 126). See figs. 12.35, 12.36, 12.37 and 12.38.

Historians write the following: “Athena is one of the most important figures, and not just in Olympian mythology: she is equal to Zeus in importance, and occasionally even excels him” ([533], Volume 1, page 126).

She is considered “an embodiment of military power . . . among the mandatory attributes of Athena is the aegis, or a shield of goatskin decorated by the head of Medusa of great magical power, feared by gods and men alike (Hom. II. II 446-449)” ([533], Volume 1, page 126). Once again, the macabre symbolic of the appalling Gorgons. Thus, the cult of the “ancient” Athena, goddess of war, must have formed after the XIV century, hence the gorgon on her shield – a symbol of St. George the Victorious = Genghis-Khan = Ryurik = Georgiy Danilovich (see figs. 12.37 and 12.38).

The name Athena is a possible reflection of the well familiar name Phan or Than – the land of Than, or Don. The full name of the “ancient” Athena, which is Athenaia Parthenos, might be reflecting the phrase “P-Russia, Land of the Than”. Nowadays “Parthenos” is translated as “virginal”.

The above makes it interesting to re-read such passages as the following, which is taken from the “Mythology of the World” encyclopaedia and reflects the Scaligerian point of view: “The myth of the gorgons reflects the motif of Olympian gods and their heroic offspring combating the chtonic forces” ([533], Volume 1, page 316). Everything is perfectly clear here – this myth does indeed date from the distant nebulous past, namely, the XIV century A. D. The “chtonic” forces, allegedly an adversary, can also be identified as the Khan’s, or Than’s armies (George’s armies, Khans from the Don).

11.6. Ares, God of War: Ross (Russ)?

Apart from Athena, “Classical Greece” also had a male god of war – Ares, whose name is very obviously a derivative from Ross or Russ.

What do we know about this deity? The encyclopaedia reports the following: “Ares, God of War in Greek mythology, war of the cruel and treacherous kind, which distinguishes him from Athena Pallas, goddess of fair and just warfare. Initially Ares [Ross – Auth.] was simply associated with war and lethal weaponry . . . the most ancient myth of Ares testifies to his non-Greek Thracian progeny (Hom. Od. VIII 361. Ovid. Fast. V 257)” ({533], Volume 1, page 101).

Everything is perfectly clear here as well. The “Thracian” god of war Ares = Ros, is apparently of Russian and Tartar origin, and formerly symbolised Russia as the Horde and the Ottoman Turkey. Must be one of the oldest images of the “Mongolian” conquest to have reached us from the distant XIII-XIV century. Ever since the Reformist XVII century, Ares has been depicted as follows: “Even the heroic offspring of Ares is characterised by unrestrained violence, savagery and cruelty . . . His horses . . . were called Flash, Blaze, Noise and Terror; his attributes are spears, burning torches, dogs and vultures” ([533], Volume 1, page 101).

Once again we recollect the imaginative yet somewhat strained exclamations of Matthew of Paris about the “savage Mongols” menacing the world, qv in CHRON4, Chapter 18:17.

The Encyclopaedia tells us further: “His [Ares’s – Auth.] epithets were as follows: ‘the mighty’, ‘the enormous’, ‘the swift’, ‘the enraged’, ‘the malignant’, ‘the treacherous’, ‘the slayer of men’, ‘the destroyer of cities’ and ‘the bloodstained’. Zeus calls him the most loathsome deity of all, saying that he would send Ares to Tartarus, had he not been a son of Zeus” ([533], Volume 1, page 102).

Ares, the God of War, may indeed hail from Russia, or the Horde, which, as we have already seen, became known in the West as Tartarus = Inferno = Terror around the XVII century – a “prison of nations”, or some such place. The emotions of the Western authors of this terminology are easy to understand. Ares became one of the most macabre incarnations of the “Mongol conquest” as seen by the West Europeans of the Reformation epoch.

Incidentally, the wife of Ares, god of war, is none other but “the gentlest and most beautiful goddess Aphrodite” ([533], Volume 1, page 102). The poetic myth might be reflecting the real mediaeval union of Russia, or Ares, and Turkey (Tartary) or Aphrodite = PhRDT = TRDT = Tartary (Tartarus).

Furthermore, “in Rome Ares was associated with Mars, an Italian god” ([533], Volume 1, page 102). We might be seeing a reflection of the same name in the compound word M-Ares = Mars.

11.7. The Franks, the Turks and the Tartars. Paris, the Persians and the Russians.

After the Trojan War of the XIII century A. D., the name “Turks” (TRK) is likely to have received two vocalisations – “Turks” and “Franks”. The former stayed in Turkey, and the latter migrated to Europe, transforming into the name of France, or Francia – possibly, as a result of the XIV century “Mongolian” conquest. In later documents the name Franks was occasionally used for referring to crusaders. Such fluctuations of the term TRK between the East and the West can be explained by the fact that one and the same name of the Tartars would be attached to different warring factions during the civil wars within the Great = “Mongolian” Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

The name of the P-Russians, who came from Russia, must have left a trace in Asia as the name of the Persians. Then, after the Trojan War and the ensuing “Mongolian” conquest it came to the West. Traces of this name can still be encountered there (Paris, for instance).

The situation with the “ancient” Greek myth is similar – on the one hand, the protagonist, Perseus or Paris, kills the Gorgon; on the other, he defeats his enemies with the Gorgon’s head that he put on his shield. There is always some confusion about the identity of the victorious and the defeated party in the descriptions of wars, depending on who wrote the chronicles.

11.8. Orders of St. George in Russia and in the Western Europe.

The famous Order of St. George is a military order ([936], page 408; see fig. 12.22). Let us remind the reader that the word “order” is likely to be a derivative of the word Horde.

“When the faith in St. George as an ally in battle against the infidels spread all across the Western Europe [already conquered by the Horde – Auth.] in the epoch of the crusades, this was followed by the foundation of a great many orders and societies in memory of the Holy Martyr. They were founded in almost every European country – Italy, Germany, Burgundy, Holland etc . . . Towards the middle of the XVIII century there was hardly a single country in Europe that would not have an Order of St. George of its own” ([936], page 408).

Let us note that Georgiy himself, or Genghis-Khan, was canonised by the Church as Great Prince Georgiy Vsevolodovich. This is how Georgiy (Genghis-Khan, and not just his angel) became known as St. George.

We must also remind the reader that St. George is present on a number of Western European countries, which is also likely to be a vestige of the conquest of Europe by Russia, or the Horde. It turns out that the persons decorated by the Cross of St. George and the Order of St. George were wearing the memory of the Russian Empire, or the Horde, on their chests – the memory of Georgiy Danilovich (Vsevolodovich) = Ryurik = Genghis-Khan = Mstislav the Valiant = the “ancient” Perseus.

11.9. Georgiy the Victorious seizes Jerusalem = Constantinople. The Bosporus as the Sound of St. George.

According to mediaeval sources, the strait of Bosporus, whereupon one finds Constantinople, and the strait of Dardanelles were known under the same name in the Middle Ages – the Sound of St. George ([729], page 141).

This is what M. A. Zaborov reports: “The Sound of St. George is the name used in the West for referring to the entire Bosporus strait ever since the First Crusade. Robert de Clary uses it for referring to the entire Hellespont (Dardanelles Strait) until the end of the Bosporus. The name, - M. A. Zaborov is clearly reduced to guesswork here, - must be derived from the Monastery of St. George in Mangana, or, alternatively, the arsenal of the Constantinople citadel, which had stood proud over the Bosporus” ([729], page 141).

In CHRON4 we voice the hypothesis that the Russians took part in the conquest of Constantinople, or Czar-Grad, fighting alongside the Ottomans = Atamans. This hypothesis is indirectly confirmed by the following Western European legend of St. George, which is rather noteworthy.

Apparently, “the Crusaders who visited the legendary birthplace of St. George spread his glory all across the West, telling how he took part in the storm of Jerusalem [or Czar-Grad, as we realise today – Auth.] . . . He rode into battle as a knight with a red cross on a white cape [the so-called Cross of St. George, known in England since the XIV century; St. George is considered the Patron Saint of England” ([533], Volume 1, page 274).

The XIV century is mentioned for a good reason – this is precisely how it should be, according to our reconstruction. It is the epoch of the “Mongolian” conquest.

The conquest of Jerusalem = Constantinople as described above is dated to 1099 today ([533], Volume 2, page 275). However, if we recollect the shift of 300 or 400 years inherent in the consensual chronology, we shall see that the events in question are more likely to date from the XIV or the XV century.

It is possible that Georgiy, or Genghis-Khan, really supervised the conquest of Czar-Grad personally. But even if he didn’t, the army of George, or the Horde, still went into battle with the victorious name of Georgiy, the founder of the “Mongolian” Empire, on their lips. This must be why the name of St. George became immortalised in the vicinity of the conquered Constantinople = Jerusalem as the Sound of St. George.

The legend about Syria being the birthplace of St. George is easy enough to explain – it is perfectly correct; according to our reconstruction, Syria (likewise Assyria and Ashur) is merely the reverse reading of the name Russia.

In that epoch, Russia, or the Horde, and the Ottoman = Ataman Turks have already become masters of Czar-Grad = Jerusalem and Byzantium in general. Hence the appearance of the name Syria = Russia in the Middle East, which was eventually inherited by the modern Syria. The name was brought here from Russia during the conquest of Byzantium, and stayed as one of its permanent vestiges.

A reflection of St. George, the founder of the Empire, was also cast over the ascension of Moscow in the XVI century as the capital of Russia, or the Biblical Meshech. As we shall demonstrate in CHRON6, this happened under Ivan IV “The Terrible” also known under the moniker “Dolgoroukiy” (literally, “long-armed”), hence the legend about the foundation of Moscow by Youri Dolgoroukiy. Khan Georgiy the Victorious, the founder of the entire “Mongolian” Empire, could obviously be included in the symbolism of Moscow as the new imperial capital.

Our theory is confirmed by the data cited by N. A. Soboleva: “Georgiy the serpent-slayer was a close image for the Muscovite princes, especially seeing as how tradition firmly associated George the soldier with Prince Youri Dolgoroukiy, the founder of Moscow . . . which was manifest in the construction of churches and the foundation of cities named after him” ([794], page 207).

Next we find out that, according to the ancient Russian tradition, Georgiy the warrior was also the patron of the Princes of Vladimir and Kiev ([794], page 207). N. A. Soboleva attempts to interpret the mediaeval data concerning the outstanding role of St. George the Victorious in the life of the ancient Russia as a mere “theory”.

She writes: “This theory, supporting the policies of the Muscovite Great Princes and reflecting their ancient origins, appeared at the end of the XIV century [which is in perfect correspondence with our reconstruction – Auth.], and remained one of the primary political theories of the Russian state throughout the entire XV century . . . We believe this to explain the particular fondness of George the warrior exhibited by the Muscovite princes . . . The Muscovite princes didn’t merely claim a relation to the deeds of George the warrior, but also associated his physical appearance with themselves. This is why the Muscovite coins often portray the Great Princes as dragon-slayers (sans halo); for greater illustrative value, such portraits were accompanied by the legend “к” or “кн”, which stood for “Prince” (“князь”). The same rider figured on the metal seals of Ivan III.

Therefore, the emblem depicting a mounted warrior slaying a dragon with his spear becomes firmly associated with the Muscovite princes in the XV century” ([794], page 207).

Our reconstruction makes everything perfectly clear. The image of St. George on the emblems of the Muscovite princes should be interpreted literally and not metaphorically, especially given the legend “prince”: Great Prince Georgiy the Victorious, also known as Genghis-Khan.

N. A. Soboleva proceeds to make the following justified observation: “The image of a mounted warrior, characteristic for the royal seals of the Western European countries during this epoch [the XIV-XV century – Auth.], makes it typical in the pan-European context” ([794], page 208). Quite correct – the Horde symbol of St. George, or Genghis-Khan, should naturally have been present on the national crests of the countries controlled by the Russian Horde during that epoch.

Now let us ask the following question. Why is St. George portrayed killing a dragon? What did the dragon symbolise? All sorts of hypotheses are possible here. Although the issue isn’t that important to us, let us suggest the following version.

On some of the Russian icons and seals St. George kills a unicorn and not a dragon ([794], page 212). We reproduce one of such icons in figs. 12.39 and 12.40. A unicorn is a mythological beast, marginally similar to a rhinoceros – a beast with a horn, in other words. See CHRON7 for more information concerning the dragon, or the unicorn, killed by George. What is the symbolism of the horn as the attribute of a certain entity defeated by George?

We must recollect one of the primary victories of George’s army, or the Horde – the conquest of New Rome, or Czar-Grad. The golden horn is one of the main symbols of New Rome. It is the famous name of the bay where Constantinople is situated (see fig. 12.41). This is what J. Assad tells us in this respect, for instance: “The ancient name ‘Golden Horn’ is derived from the shape of the bay, which resembles a cornucopia. The Golden Horn bay is approximately 11 kilometres long; its average width is 450 metres, and the maximum depth equals 45 metres. Its coastline is not quite as meandrous as that of the Bosporus, and constitutes an enormous harbour, very convenient even for the largest ships and doubtlessly a safe haven for small vessels.

This convenient disposition has always attracted people’s attention to the capital city of Byzantium” ([240], page 19).

The Golden Horn Bay had a great military and strategic importance. The defenders of the city locked it with a huge chain placed across the entrance to the bay, which precluded the enemy ships from sailing inside ([240]).

When New Rome = Czar-Grad was captured in the Trojan War, its symbol, or the Golden Horde, depicted as a unicorn, ended up on the crest of St. George the Victorious as the symbol of the defeated capital city of Byzantium. George struck down the “unicorn”, or the Golden Horn of Czar-Grad. In other words, the picture of St. George slaying the unicorn, or the dragon, had initially conveyed the simple and understandable idea: the army of George defeated and captured New Rome.

Therefore, it is likely that the world-famous coat of arms with St. George is a symbolic representation of the Trojan War, or the battle for Czar-Grad and the victory over the Golden Horn.

We have already witnessed the real events of the distant XIII-XIV century reflected on the pages of the Bible. Does the Bible contain any references to this association of New Rome with a unicorn or a rhinoceros? Apparently, yes.

It was already pointed out by N. A. Morozov in the fifth volume of his oeuvre entitled “Christ” ([544]), that the Hebraic and Chaldaean dictionary of O. N. Sternberg indicates the following: “RAM and ROM, RAIM or ROME is a kind of antelope, according to the latest research . . . This word is mentioned in the Book of Numbers (23:22), Psalms (psalm 92:11 and psalm 22:22), Job (39:9) and Isaiah (34:7). A young animal would be called the son of Rom (psalm 29:6)”. Quoted according to N. A. Morozov ([544], Volume 5, page 353). Sternberg refers to the psalms in Hebraic enumeration. The corresponding passages in the Synodal version are as follows: Psalms 91:11, Psalms 22:21 and Psalms 29:6.

N. A. Morozov is perfectly correct to point out that the corresponding Biblical texts referring to an animal called RIM or ROM are hard to associate with the image of a trembling antelope. This is what we read in the Bible: “Save me from the lion’s mouth: for thou hast heard me from the horns of the unicorns” (Psalms 22:21). It is most likely to be referring to a rhinoceros – a fierce and dangerous animal, whose image must have been associated with Czar-Grad = Troy.

11.10. The sound of St. George in Britain.

Let us remind the reader of our research dealing with the history of Britain, qv in CHRON4, Chapter 18:9. We have put forth and substantiated the hypothesis that initially, in the XI-XIII century, the city of Troy = Czar Grad was also called London in a number of chronicles. Then, after the fall of Constantinople and the escape of some of its residents to the West, the name migrated to the British Isles, and was given to the new capital city founded here.

Apparently, the former name of the Bosporus Strait (the Sound of St. George) also migrated to the British Isles, likewise London, and became recorded on later maps as the Sound of St. George, which separates Great Britain from Ireland. See the ancient map of 1750 entitled “Mercator’s Map of America or the West Indies” – a copy from the original that was kept in the study of Peter the Great, qv in [73] and in fig. 12.42.

The sound that separates Great Britain from Ireland is called the Sound of St. George. The name is used until the present day, and can be found on any modern map.

It is however possible that the name of St. George the Victorious, or Genghis-Khan, came here directly and not by proxy of Czar-Grad, during the Great = “Mongolian” conquest of the XIV century. The troops of the Horde marched all across Europe under the banners of St. George = Genghis-Khan, and subsequently reached the British Isles. Having founded a large settlement here, they named the local strait after George, likewise the strait where the recently conquered Czar-Grad had stood. This was the very “Roman” conquest of Britain, so famous in Scaligerian history.