Part 4.

Western European archaeology confirms our reconstruction, likewise mediaeval cartography and geography.

Chapter 14.

The real contents of Marco Polo's famous book.

12. Miniatures in the book of Marco Polo.

12.1. What did they depict?

Unfortunately, most readers of [1264] won’t have an opportunity to see the overwhelming majority of miniatures contained in the old manuscripts of Marco Polo’s book. The fundamental edition ([1264]) claims completeness and contains a large number of illustrations, but, oddly enough, nearly all of them are modern drawings of the South-East Asia. The truly old and authentic drawings from the manuscripts of Polo’s book are few and far between. Why would that be? Why couldn’t the publishers of [1264] reproduce all of them, or at least the numerous surviving illustrations from the mediaeval manuscripts of Marco Polo? They are exceptionally interesting and important, after all, since they reflect the views held by the West Europeans of that epoch on “India” and “China”.

The book ([1294]) even contains a list of miniatures contained in two old manuscripts of Polo’s book ([1264], Volume 2, pages 527-529). Apparently, the first manuscript contains 84 ancient miniatures, and the second, 38.

12.2. Miniature entitled “The Death of Genghis-Khan”.

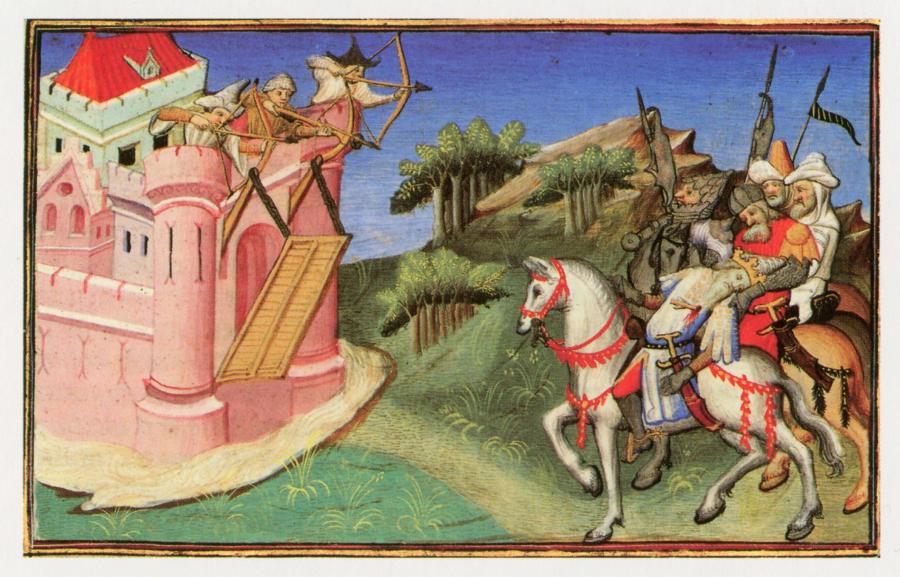

In fig. 14.4 we reproduce an ancient miniature from Marco Polo’s book entitled “The Death of Genghis-Khan”. It can be found in the large volume entitled “Le Livre des Merveilles” (Fr. 2810), which is kept in the French National Library ([1264], Volume 2, page 527).

The drawing is virtually indistinguishable from the miniatures known to us by Russian chronicles. Stone city with towers surrounded by a river or a moat, a portcullis, groves, hills, bearded riders in chain mail and headdress indistinguishable from the Russian. In particular, we see the well familiar hats of the Russian marksmen. They are rather small in this miniature, but in the next one you will be able to make them out perfectly well.

Commentators believe that the picture depicts a part of the modern Mongolia, in the steppes next to the border of China. But what precludes us from seeing a typically Russian theme in this miniature? Nothing at all, since we see absolutely no details that look Chinese.

It must be pointed out that Genghis-Khan died in the siege of a city interestingly enough named Calacuy (Kaluga) in the French edition [1263], page 68. On the other hand, many Russian chronicles describe the Battle at Kalka, where the South Russian and Polovtsy Princes were defeated by the army of Genghis-Khan in the alleged year 1223 ([942], page 29). Apparently, Russian chronicles and Marco Polo describe the same battle, although Russian sources do not mention anything about Genghis-Khan dying in this battle. Thus, the text might be referring to the battle at Kaluga, or Kalka.

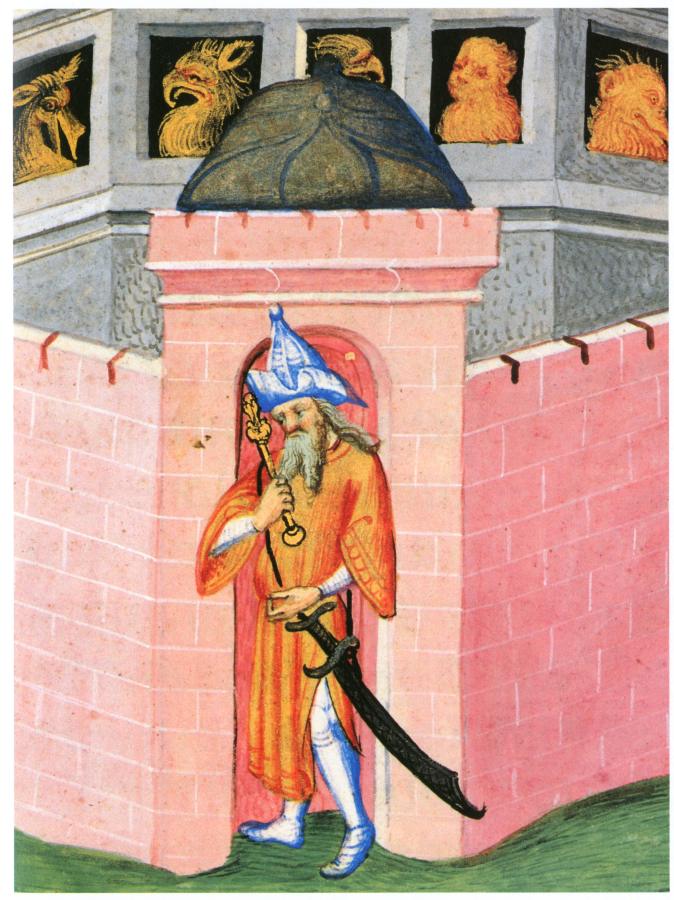

12.3. Miniature entitled “The Palace at Khan-Balyk”.

In fig. 14.5 we cite another ancient miniature from Marco Polo’s book entitled “The Palace at Khan-Balyk”. We see brick stones, military guards that distinctly resemble the Russian marksmen in kaftans and characteristic hats (see fig. 14.6). The style of the illustration is once again nearly impossible to distinguish from the customary mediaeval Russian miniatures.

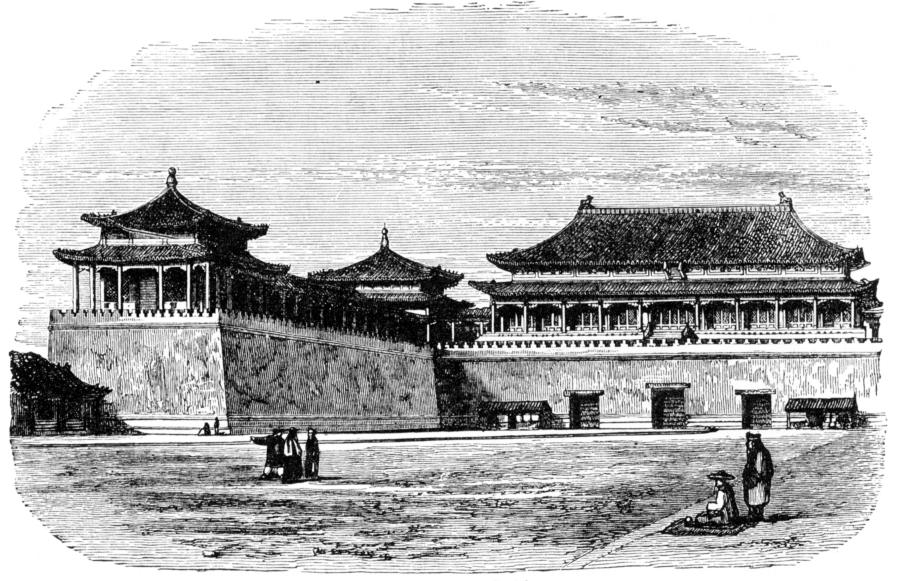

Modern publishers of [1264] decided to show the modern readers how the scene should have looked in reality – all in good faith. For this end, they complement this old miniature from Marco Polo’s book by a drawing of the Winter Palace in Beijing (fig. 14.7). They must have honestly believed this palace, or one that had looked similarly, to have served as the prototype for the old miniature. However, we see typically Chinese roofs with edges protruding upward, broad-brimmed Chinese hats that provide good protection against the sun etc – nothing remotely resembling the ancient miniature. This is a good example of how Scaligerian history copied events from one chronicle and pasted them into another, ascribing them to a different country.

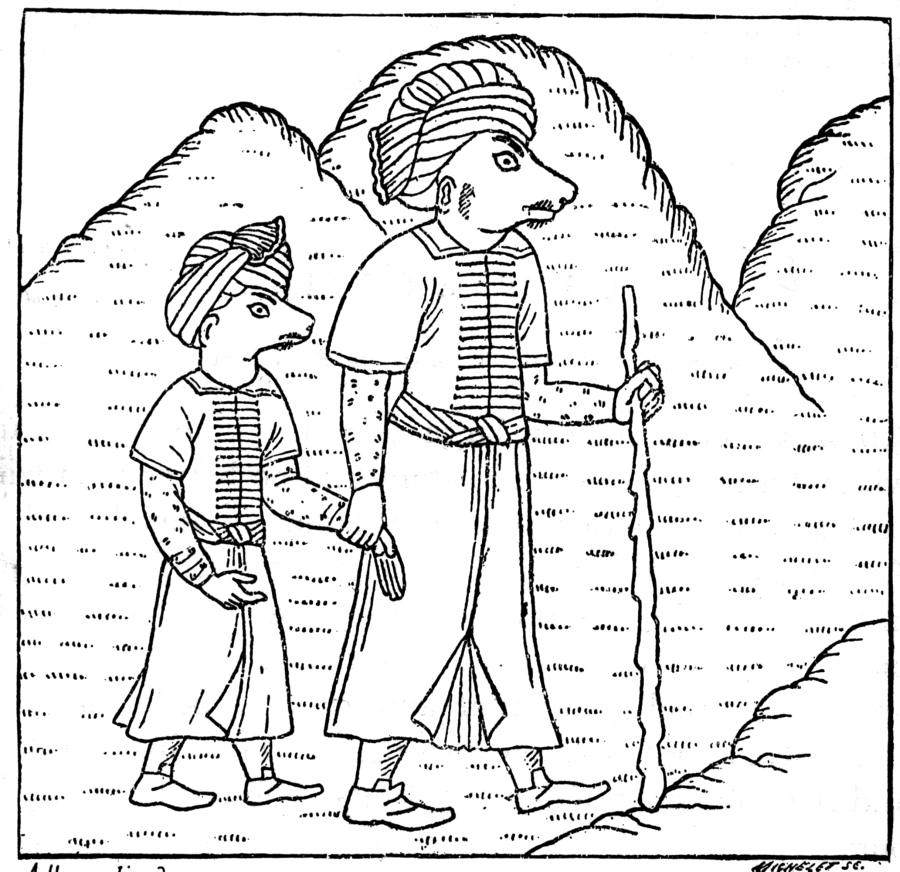

12.4. Miniature entitled “Borus” (Boris?)

In fig. 14.8 we see an ancient miniature entitled “Borus” from the book of Marco Polo. Could this “Borus” be a Boris, or a P-Rus (White Russian)? We see people with canine heads in typical Russian kaftans – mark the latches woven of cords. They wear turbans, well familiar to us as the headdress of the Cossacks and the Ottomans (Atamans).

People with canine heads are also an image that we often encounter in the “ancient” literature, Egyptian artwork and mediaeval Western texts. It is believed that these mysterious fantasy creatures only existed in the imagination of the Egyptians, the Byzantines and the West Europeans, and had nothing to do with Russia whatsoever.

The turban is believed to be a purely Oriental and Muslim headdress today, which has allegedly never been worn in Russia. The combination of a Russian kaftan, a turban and a canine head might indeed seem uncanny; let us do some explaining.

12.5. The identity of the people with canine heads.

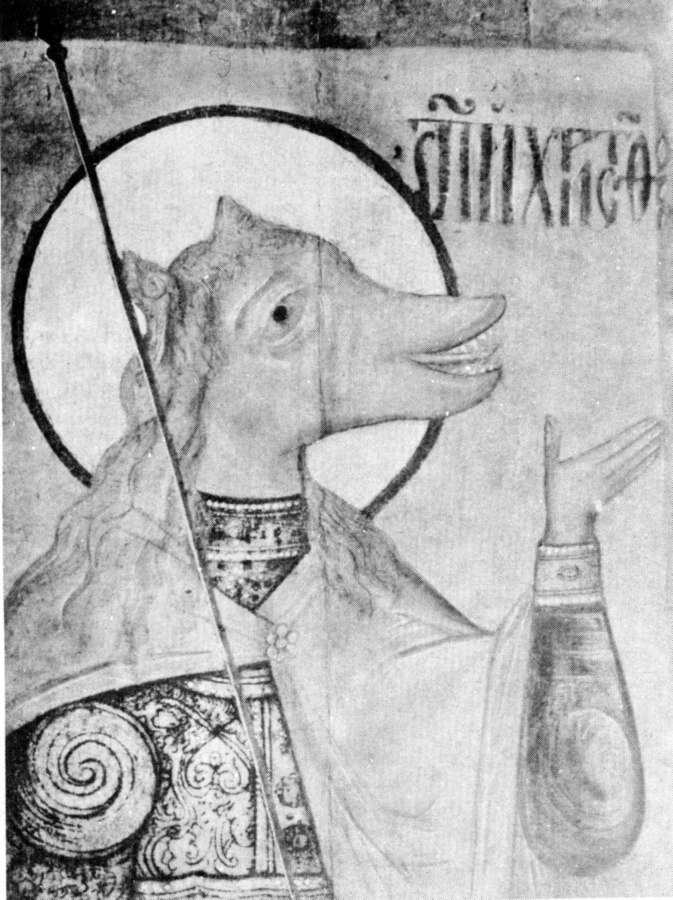

Mediaeval and “ancient” literature often mentions people with canine heads. There is an enormous amount of ancient artwork depicting such people – in Egypt, in particular. People with canine heads were also portrayed on the old Orthodox icons – St. Christopher, for instance, qv in figs. 14.9, 14.10 and 14.11.

All of it is believed to be pure fantasy like flying dragons breathing fire, without any root in reality whatsoever. Is it so?

We are of the opinion that all legends and all the artwork of this sort is based on reality – what we encounter is medieval symbolism, which must have had a definite meaning in mediaeval Russia. It is likely, although this issue doubtlessly requires a deeper research, that the dog symbol represented the guards at the court of the Russian Princes, or Khans, or some organization similar to the Prince’s Guard.

What made us suggest this version? Among other things – the commonly known fact that during the epoch of Ivan the “Terrible” the oprichniks, or warriors of the Czar’s Army, “always went around with canine heads and brooms tied to their saddles” ([362], Book 3, Volume 9, page 50). It has to be noted that Karamzin refers to the foreigners Taube and Kruse, who describe this custom. Therefore, one should not interpret this account literally – severed canine heads with beastly fangs attached to saddles are unlikely to make them more convenient for riding, and there’s the smell issue to consider as well – any horse wearing such decorations would doubtlessly panic.

We are clearly confronted with a distorted rendition of some real Russian custom involving the palace guards, who might have worn some canine symbol of a “watchdog” – the most obvious thing to symbolise a guard.

Apparently, when foreigners visited the Royal Palace of the Russian Czar, they saw the palace guards wearing a dog symbol (on their hats, for instance). This would leave an impression, and so, upon returning to Europe, they would tell their fellow countrymen about a faraway land where the palace guards “wear dogs on their heads”. The data went through a variety of hands, transforming into actual representations of people with canine heads, hence the famous “ancient” term “cynocephalic” used for referring to people with canine heads as mentioned by many “ancient” authors.

When the oprichniks started to decorate their saddles with the dog symbol, foreign renditions would transform this custom into gruesome severed dog heads attached to saddles. Modern historians are generally aware of how absurd such riders would look; thus, R. G. Skrynnikov only cautiously mentions the broom in his description of the oprichniks – not an actual broom, but “a certain likeness” thereof ([776], page 107). Not a word about any dog heads.

We instantly understand why mediaeval English sources use the names “Dogi” (“Dagi”) for referring to the Russians ([517], pages 261 and 264). The canine associations stand strong.

Thus, it is for a good reason that the cynocephalous figures on the “Borus” miniature are dressed in Russian kaftans of the marksmen – the latter had been the elite Russian troops up until the epoch of Peter the Great.

Moreover, people with canine heads were frequent characters of the mediaeval European historical chronicles – for instance, the Czech Cossacks, or “khody” (infantrymen) were known as the “dogheads”, and they had a canine head symbol on their banners.

The “dogheads”, or the Cossack infantry, resided in the Czech and Bavarian borderlands, preserving the typical Cossack lifestyle until the middle of the XVII century at least. The last time they served in the military was in 1620, which is when the Czech kingdom lost its national independence. In 1883-1884 they acted as protagonists of the novel “Dogheads” by Alois Irasek, one of the most popular novels among the Czechs. In 1693 the “doghead Cossacks” rebelled against the Habsburgs; the mutiny was suppressed. This is what Irasek’s novel writes about.

And now, what about the turban?

12.6. Turbans as native Russian headdress.

Did Russians actually wear turbans? – asks the reader in amazement. Even for us it proved surprising. However, we have discovered that they did wear turbans; furthermore, the word “chalma”, which stands for “turban” in Russian and is believed to be of a Turkic origin was really derived from the well-known word “chelo” (forehead).

Cossacks wore turbans until the XVII century – we have already reproduced a portrait of Stepan Razin, the Cossack Ataman, wearing one (see CHRON4, Chapter 3:4:1). Bogdan Khmelnitskiy the Getman was even sculpted in a turban for his modern memorial in Kiev. The etymological dictionary blatantly states that the word “chalma” is of a perfectly Slavic origin; the word translates literally as “headdress”. Another related Russian word is “shlem” (“helmet”), or “shalom” in its more archaic ofrm.

In the XVII century the only ones to wear turbans were the Cossacks, descendants of the former Horde army. Earlier on the turban must have been typical Russian headdress.

12.7. Miniature entitled “Cynocephali”.

Fig. 14.12 is a reproduction of “Cynocephali”, an ancient miniature from the book of Marco Polo. The characters portrayed therein are once again believed to hail from faraway tropical India – gathering rice in the relentless sunshine. And yet we see people wearing typical Russian clothes, as though they were copied from Russian miniatures. We have already voiced our opinion on the canine heads; let us now consider a few other interesting details.

Rice is unlikely to be gathered on a dry hill – the two open sacks that we see must contain rye or wheat. Especially seeing how the second figure on the left in the foreground is sowing seeds from a bag tied to his belt, which is virtually a Russian archetype (whereas rice is planted as seedlings on a field covered with water).

The boots are also typically Russian and resemble many Russian miniatures. Also, we see a fortified city with stonewalls once again.

Should someone prove extremely reluctant to admit that the country we see here might be Russia, it can be any country in Europe, albeit with a lesser degree of probability. However, tropical countries and South-East Asia are right out of the question.

12.8. Other miniatures from Marco Polo’s book.

In 1999 a facsimile edition of Marco Polo’s book entitled “Le Livre des Mervilles” came out in France ([1263]). The Russian translation renders the title as “Book of World Diversity” ([510]). The French edition contains about ninety luxurious ancient colour miniatures. Some of them, as we demonstrate above, are likely to represent certain events that occurred in Russia, or the Horde, which is the land where Marco Polo actually travelled. Our analysis of other miniatures confirmed this observation, complementing it by many new details. One gets the impression that the majority of the miniatures were created in the XVII-XVIII century the earliest. We are referring the readers who express further interest in the subject to [1263]. Presently, we shall just reproduce a few of those miniatures in order to demonstrate how European artists depicted the Great Empire – probably, in the XVII-XVIII century. They must have based their artwork on some authentic old miniatures, with the inevitable introduction of new motifs, occasionally fable-like.

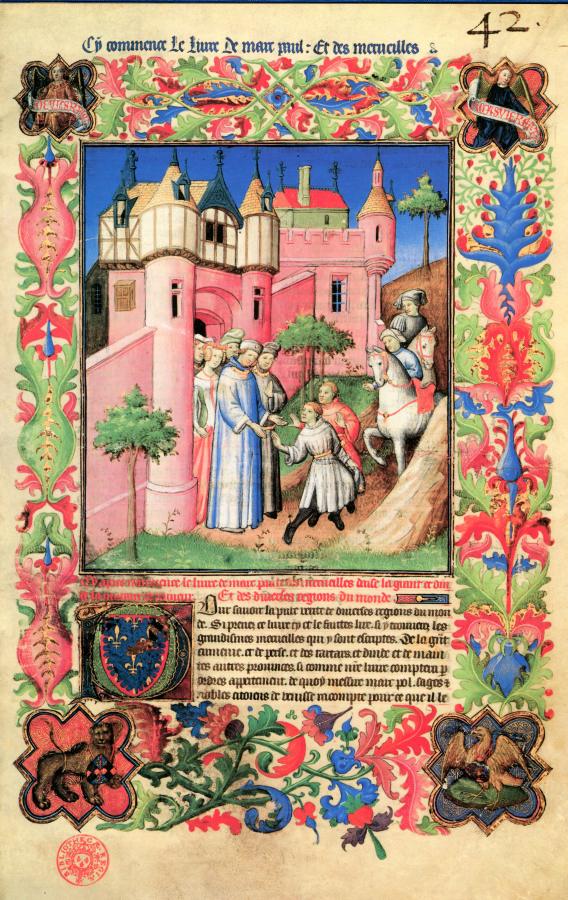

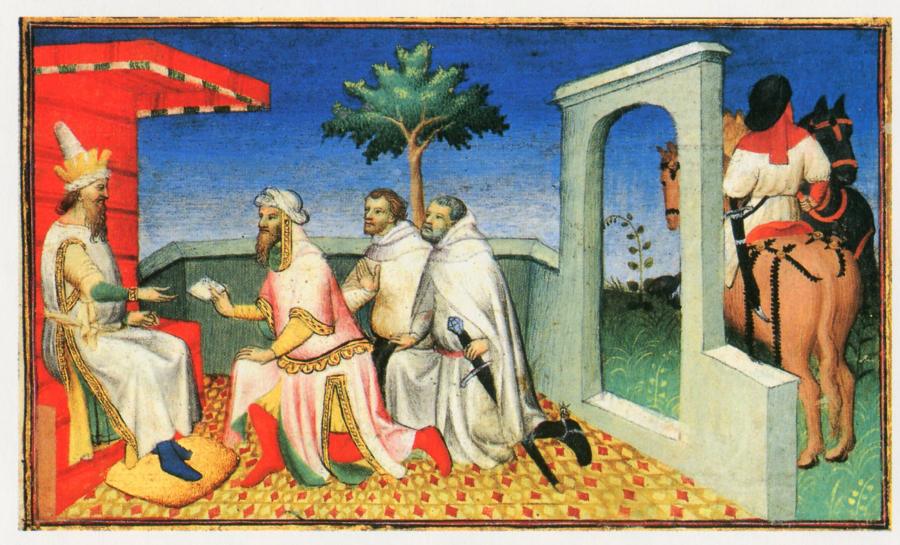

1) The book of Marco Polo opens with a luxurious colour miniature that depicts the beginning of the voyage of Nicholas and Matthew Polo, setting forth from Constantinople (fig. 14.13). One instantly notices the extremely expensive and festive layout. A propos, the herbal patterns in colour resemble the ornamentation on the handwritten Russian books of the XVI-XVIII century.

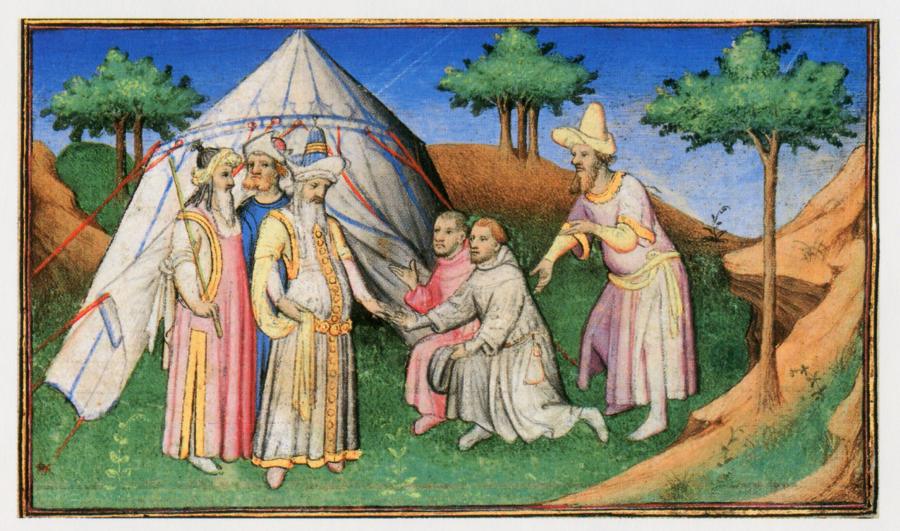

2) Nicholas and Matthew Polo in Bukhara, Persia (fig. 14.14). We see a field tent on a meadow – there is nothing specifically southern, or Persian, about the landscape.

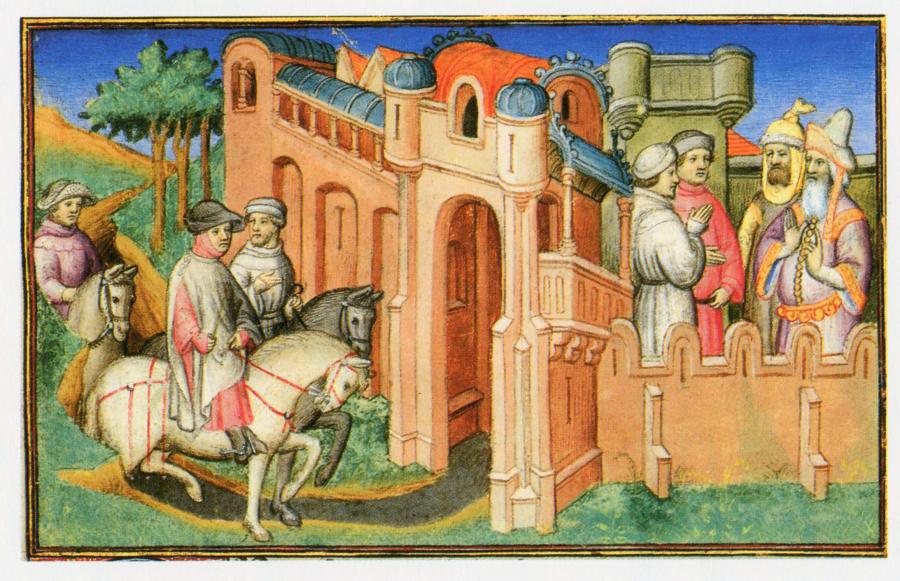

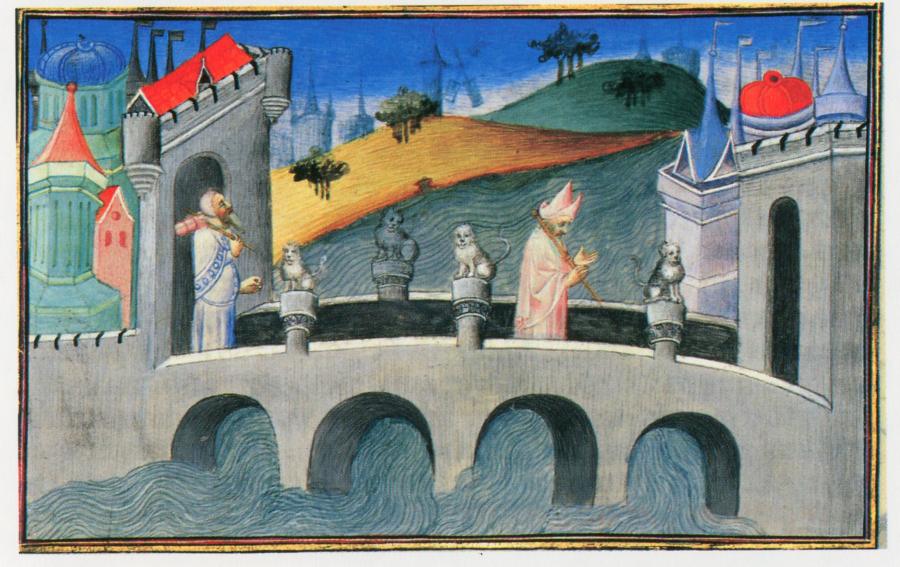

3) Nicholas and Matthew Polo approaching the gateway of the Great Khan’s capital (fig. 14.15). We see a city of stone among the meadows; the Khan and his entourage look perfectly European.

4) In fig. 14.16 we see the Great Khan receiving the Papal epistle. The faces of both the Khan and his courtier who hands over the letter are distinctly European – they have long fair beards. The abundance of red must be emphasising the royal ancestry of the Great Khan. Let us remind the reader that the colour red was associated with royalty in mediaeval Byzantium and Europe. As we see, the same symbolism was common for the court of the Great Khan.

5) In fig. 14.17 we see Nicholas and Matthew Polo receive the “golden board” from the Khan – a travel voucher for their journey through the Empire. The Khan is also wearing a golden helmet on his head, likewise his courtier. Such hats, or helmets, were formerly worn in Russia.

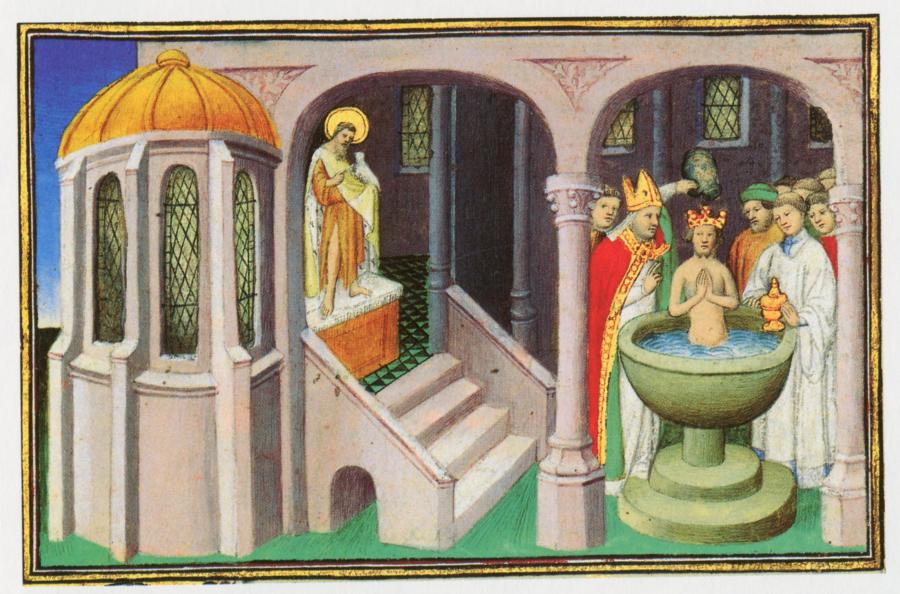

6) In fig. 14.18 we see the Christian baptism of the Great Khan’s brother in the city of Samarqand ([510], pages 70-71). The city in question is likely to identify as Samara in Russia. Samarqand must stand for “Samara-Khan”.

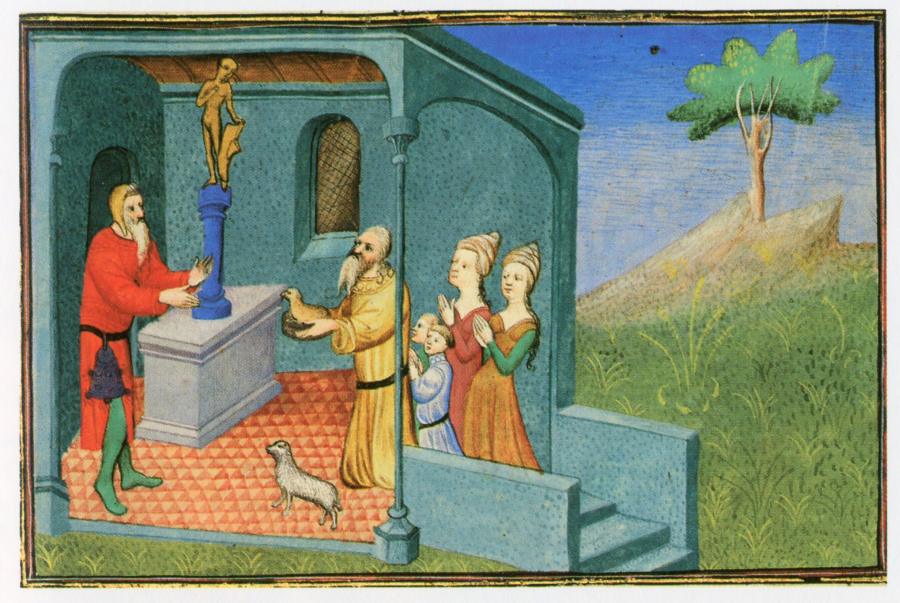

7) In fig. 14.19 we see the worship of a golden idol in Tangut. People with European faces, dressed in European clothing, are shown worshipping a golden idol. Apparently, what we see is a prayer in an Orthodox temple in front of gilded icons, depicted as a golden idol statue by the West European artists, who didn’t quite grasp the matter. Incidentally, the actual name “Tangut” must stand for Tan, or Don Goths – Cossacks, in other words.

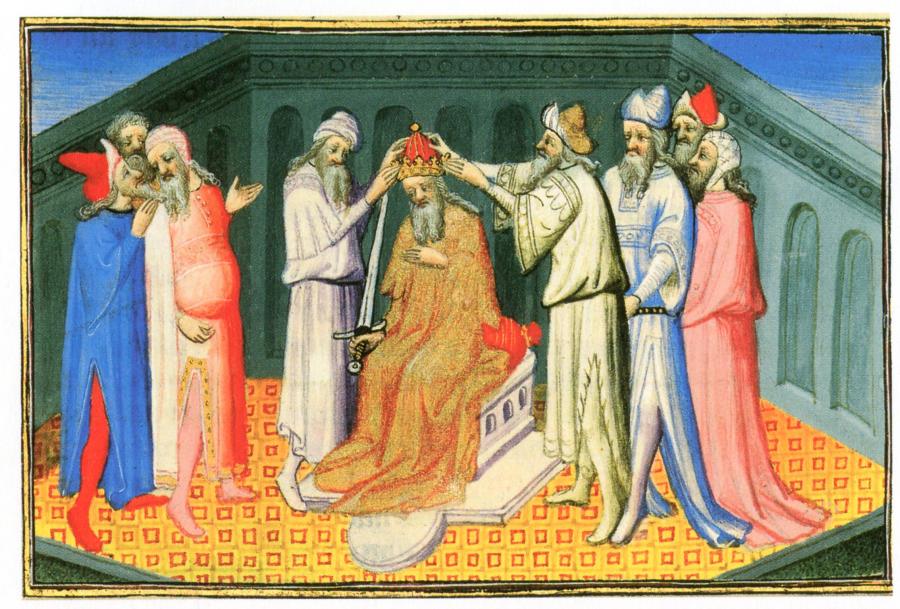

8) The inauguration of Genghis-Khan (fig. 14.20). Depicted as the inauguration of a Roman Emperor, which must reflect reality. According to our reconstruction, Genghis-Khan must have been inaugurated as the emperor of the whole Empire – a Roman Emperor, in other words.

9) The suit of Genghis-Khan to the daughter of a Great Khan (fig. 14.21). Presbyter Johannes takes letters with red royal seals from Genghis-Khan. Presbyter Johannes and the people by his side look distinctly European and wield crosses. Actually, the envoys of Genghis-Khan also look European; the palace of Presbyter Johannes looks like a European building.

10) In fig. 14.22 we see the beginning of the battle between Great Khan Kubilai (Kublah) and his uncle Nayan or Nayam (the French edition calls him Naiam – see [1263], page 82). Nayam lays next to his wife it a tent surrounded by troops. Kubilai attacks him. A bloody battle ensues, with many casualties ([510], pages 110-117). According to our reconstruction, this battle was the very famous Battle of Kulikovo dating from 1380. Kubilai identifies as Dmitriy Donskoi, whereas Nayam-Khan is Mamai, the Khan from the Russian chronicles. Bear in mind that the letters M and N often got confused, especially in Western European texts, where they were both represented by virtually the same symbol – a tilde over the preceding vowel, qv in CHRON5, Annex 1. Our in-depth analysis of how Marco Polo describes the Battle of Kulikovo can be found in CHRON4.

11) In fig. 14.23 we see the four wives of Kubilai-Khan, or Dmitriy Donskoi, as we understand it today. We can also see his sons. All four wives look distinctly European – moreover, they are blondes. The sons also have fair hair. We see no Mongolian features (in the modern meaning of the word). One cannot help noticing the attire of the Great Khan’s wives – their dresses are European through and through. All of them are wearing golden trefoil royal crowns on their heads.

12) In fig. 14.24 we see a bridge over the River Pulisangin next to the Great Khan’s capital. There is a windmill in the distance. The bridge itself, as Marco Polo tells us, stands on 24 arches and just as many watermills ([510], page 166). Windmills are a typical element of Russian landscape (as indeed the European landscape in general). Watermills were very popular in Russia. As for the steppes of the modern Mongolia, we doubt the existence of mills there, especially watermills. Actually, the name Pulisangin might be a derivative from the Russian word “plyos” (“river reach”) – possibly accompanied by a name of some sort.

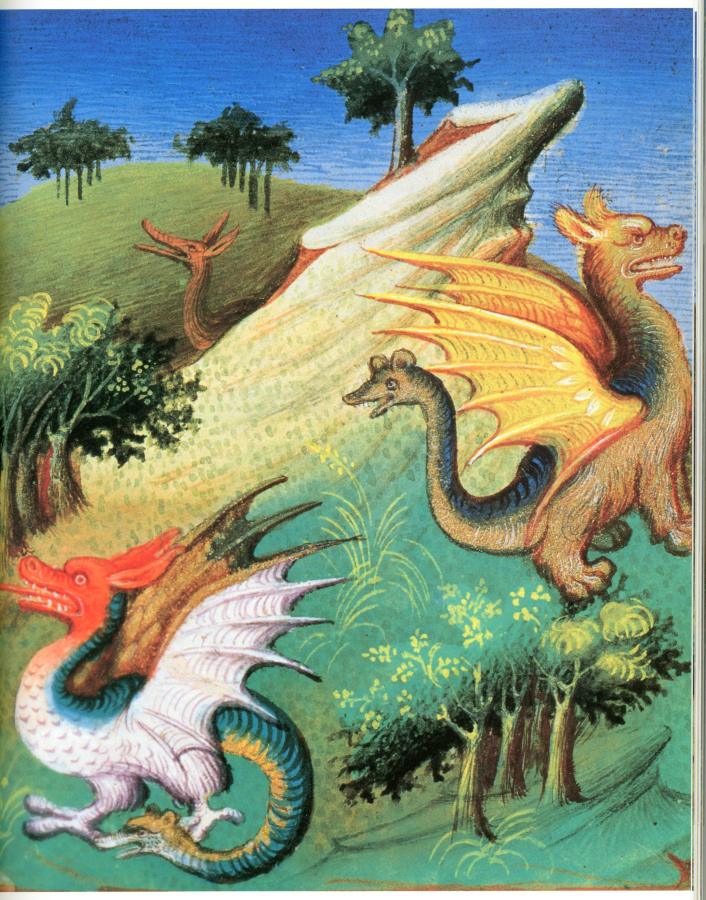

13) In fig. 14.25 we reproduce a miniature from Marco Polo’s book that is presumed to depict the fantastic serpents from the kingdom of the Great Khan. Marco Polo gives us a detailed description of how the Great Khan’s subjects hunt these serpents: “Large adders and enormous serpents live here . . . They are truly fat and huge: the largest are about ten paces long and ten spans wide. They have two limbs in front, right near the head – no paw, just claws, like those of a falcon or a lion. Their head is tremendous, and their eyes are larger than loaves of bread. Their snout is so wide that they can swallow a human, and the teeth are so big and so strong that there is no man or beast alive that wouldn’t fear them. Some are smaller – eight paces or five paces long, or just one pace. This is how they are hunted . . . the hunters set a trap on their path – they dig a thick and sturdy wooden pole into the ground with a keen metal end, sharp as a razor or a spearhead . . . The serpents crawl along that path and impale themselves upon these poles so that they are pierced up to their very snout, and instantly die; this is how the hunters catch them . . . and, let me tell you, the meat of these serpents is sold dearly; it is tasty and a welcome delicacy” ([510], page 188).

One wonders about these “tasty serpents”, fat, with eyes larger than bread loaves and large snouts, killed with the use of poles driven into the ground that these beasts impale themselves on? Anyone wishing to think that the author is writing about the hunting of some strange animal that became extinct ages ago and remain a mystery to the modern science is free to do just that. We shall voice a simple consideration. The author is telling us about the famous Russian bear hunt. Bear hunters do the following: when the bear attacks and stands up straight, a sharp pole is driven into the ground in front of it instantly; the furious animal hurts itself against the sharpened end of the pole and keeps pressing onward without realising the danger of doing so, finally dying pierced by the lethal weapon – the bears “kill themselves” in a way, which is precisely what Marco Polo tells us about. The authentic text of Marco Polo (or the Pole) has not reached our day and age – only a later Western European version of the XVII-XVIII century did.

Western European editors of Polo’s book must have been completely unfamiliar with such hunting, and introduced fantasy elements into Polo’s text. They even drew a picture in colour, awed and aiming to awe their readers (fig. 14.25). The serpents look truly terrifying – however, they somehow made one of them look very much like a bear, paws, snout and all, the fantasy tail and wings notwithstanding (see fig. 14.26).

It is therefore perfectly obvious that Marco Polo’s book has undergone some heavy editing. The editors from Western Europe may have honestly tried to understand the old text that they were processing; however, by either failing to understand it or deliberately making things obscure, they have transformed the original work of Marco Polo (the Pole) into a fairy tale, which nonetheless contains some traces of the real state of events, just like the miniatures with bear paws and snouts showing through.

Whence appeared a name "snake" for Russian bear in the book of Polo? We formulate the hypothesis here. In Latin, the BEAR is URSUS or URSA [237], sec.1048-1049. A Latin word for Snake is: serpens or MORSUS [237], p.923. It is quite clear that words URSUS and MORSUS could easily be confused converged into each other. Editor or translator of the XVII-XVIII centuries, already barely understanding the nature of the matter, could readily turn the BEAR-URSUS into SNAKE-MORSUS. After which the artists took up the brush and confidently painted a winged snake-bear. It turned out fantastic.

13. The “Kuznetskiy Most” in mediaeval China.

We read the following in Marco Polo’s book: “Let us now consider the great Bridge that crosses the River in this city. The bridge is made of stone, seven paces wide and half a mile long . . . There are marble columns on both sides of this Bridge; they support the roof. Thus, the Bridge is fully covered with a roof, and lavishly decorated. There are houses upon this bridge, and they are all made of wood: put up in the morning and taken away in the evening [? – Auth.]. Also the Customs of the Great Khan can be found upon the bridge – this is where they collect fees and tax for his benefit. I must tell you that the deals made on the Bridge bring the Suzerain thousands of gold pieces every day, and maybe even more” ([1264], Volume 2, page 37).

The description is thoroughly strange. What’s the use of a bridge across a river? It is a means of crossing it, that’s right; moreover, crossing it without much tergiversation so as not to block the way. Have you actually seen any bridges that would support houses? Even in China? One might think that Polo’s account is an exaggeration of some sort; however, another point of view is also viable. The Russian word for “bridge” (“most”) also translates as a “paved street” (the verb for “pave” is “mostit”).

This makes everything perfectly normal. Such paved streets have indeed been known as vibrant marketplaces for centuries – suffice to recollect the Kuznetskiy Most Street in Russia, historically the location of the most expensive shops in Moscow; it is paved in stone.

Once again, the restoration of Polo’s text to its original location – Russia, or the Horde, makes its formerly obscure and incomprehensible parts perfectly clear.