Part 4.

Western European archaeology confirms our reconstruction, likewise mediaeval cartography and geography.

Chapter 15.

The disappearing mystery of the Etruscans.

12. The appearance of the Etruscan lettering.

12.1. Which inscriptions are considered Etruscan.

In the present section we shall get our readers acquainted with the results of Faddey Volanskiy ([388]).

According to A. I. Nemirovskiy, “in the Renaissance epoch . . . all the lettering found in Italy that differed from Latin graphically was presumed Etruscan” ([574], page 75).

Etruscan studies have made great advances without having deciphered a single Etruscan inscription so far. Nowadays Etruscan scholars already distinguish between Etruscan and other lettering. We shall refrain from relating the intricacies of this classification here and stay on the initial position of the Renaissance epoch for the sake of simplicity.

If there was a tradition in the Renaissance Epoch that pronounced all incomprehensible and graphically non-Russian inscriptions found in Italy Etruscan, we are inclined to trust this very local tradition.

The important thing is not how you call the inscriptions that remain illegible, Etruscan or not, but whether or not they can be read. Since Volanskiy claims they can be read “almost in Russian”, it justifies their name – “Etruscan”.

According to Volanskiy, “the Gets [Goths – Auth.] also pertained to the Slavic tribe of nations – there were many tribes known: the Massagets, the Mirogeds, the Tissagets, the Tiragets, the Samogets, the Thracogets etc. Maybe the Russian Gets “gety russkie”, which used to occupy a part of Russia . . . gave the Etruscans their name.

As the oldest legends have it, they called themselves Rasi, or Russians . . . The Etruscan (or Osco-Umbrian) alphabet, known well to everybody, has undergone a great many changes . . . ever since the emergence of these tribes in history and until they became completely mixed with the Latin nations, their neighbours . . . The latest artefacts that shortly predate the complete assimilation of these Slavs . . . demonstrate a modified alphabet; however, we find the two languages woven so closely together that purely Slavic words become conjugated in the Latin manner, and, au contraire, Slavic curves render Latin expressions. The two languages gave birth to Italian” ([388], page 85).

A propos, let us consider the influence of the Slavic languages over Latin. Just a number of examples.

a) The Russian word “iskhod” transforms into the Graeco-Latin “exodus”, which has the same meaning.

b) The Russian “kisten” (a weapon that resembles a morning star) transforms into the Latin “coestus”, which is a similar weapon. This was noted by the XVI century traveller Sigismund Herberstein: “Their usual weapons [the Muscovites’ – Auth.] include bows, arrows, axes and a kind of mace that resembles the Roman coestus, called kisten in Russian” ([161], page 114).

c) As we have pointed out already, the Old Russian word “inde” (“somewhere”, “far away” etc, qv in [786]) has transformed into the Latin inde with a similar meaning “thence”, “from that place” and so on (see [237], page 513).

It goes on like this; more details can be found in the Glossary that we have compiled (see end of CHRON7 and our book <<Russian roots of “ancient” Latin>>).

Basing his research on Slavic languages, Volanskiy makes several successful attempts of reading not just the Etruscan script as found in Italy, formerly indecipherable, but also many other inscriptions considered illegible previously, which were found in Europe. Volanskiy is of the opinion that they can be deciphered as Slavic.

12.2. The Etruscan alphabet.

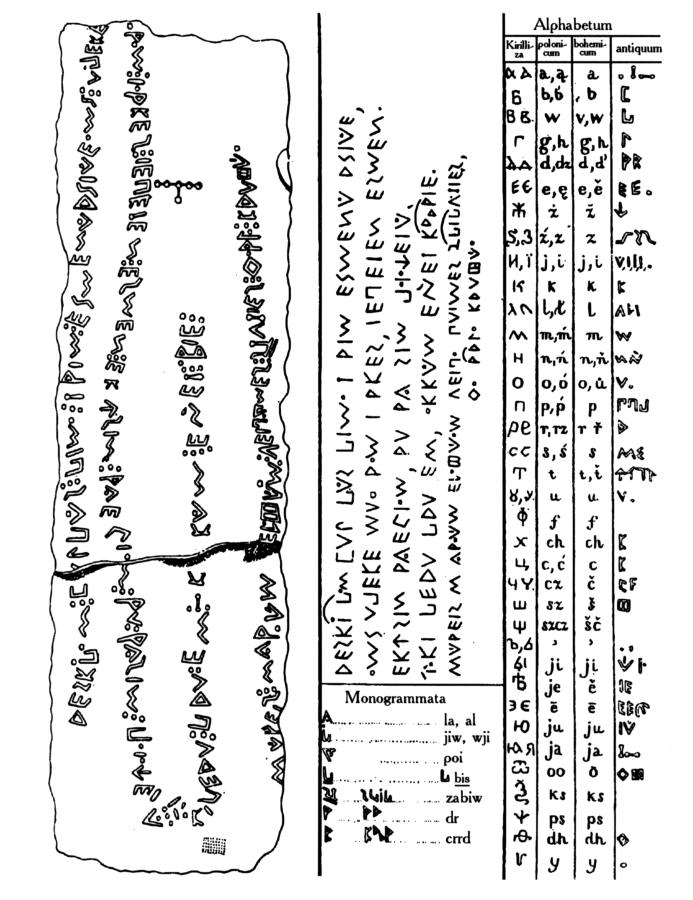

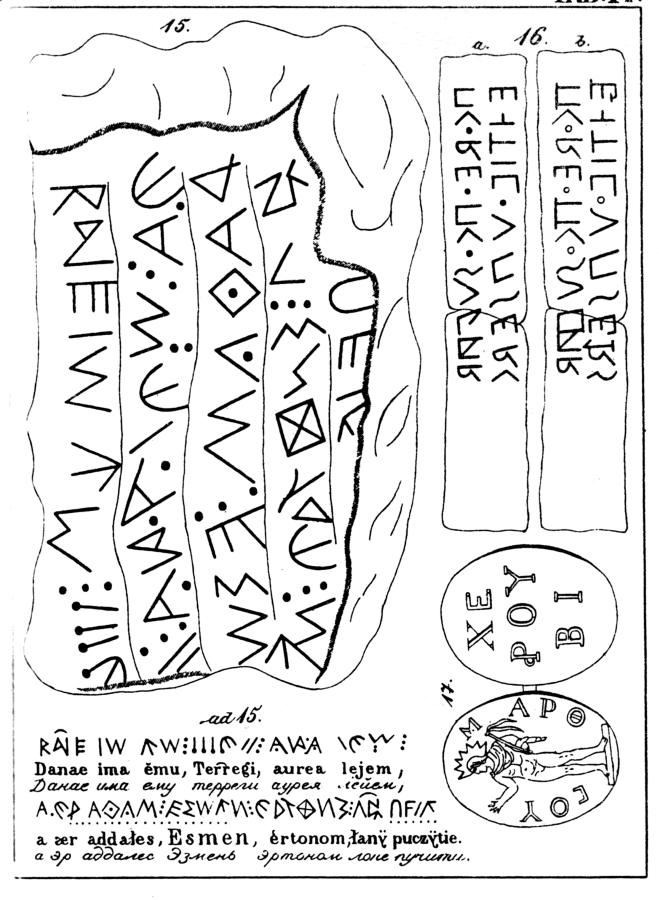

The Etruscan alphabet is reproduced in fig. 15.7 (far right column). The previous three columns demonstrate the correspondence between the Etruscan letters and the customary Cyrillics (first column), Polish letters (second column) and Bohemian letters (third column). Complex symbols comprising several are in the bottom left part of the table. A propos, Cyrillic script had a number of complex letters as well – “ia”, “iou”, “ksi”, “psi” and so on.

The table was borrowed from the work of Volanskiy ([338], page 103). Pay close attention to the similarity between the Cyrillic letters and their Etruscan counterparts from the fourth column. About a third of all the letters found in Etruscan alphabet are the same as their Cyrillic counterparts. Actually, we have already cited a XVII-century Russian inscription where only about one third of all letters were Cyrillic, and other symbols used for representing all the others (see CHRON4, Chapter 13:6 and CHRON5, Chapter 3:1). We see a similar situation to be the case with the Etruscan alphabet – Cyrillic letters comprise one third of the alphabet; the remaining symbols are different.

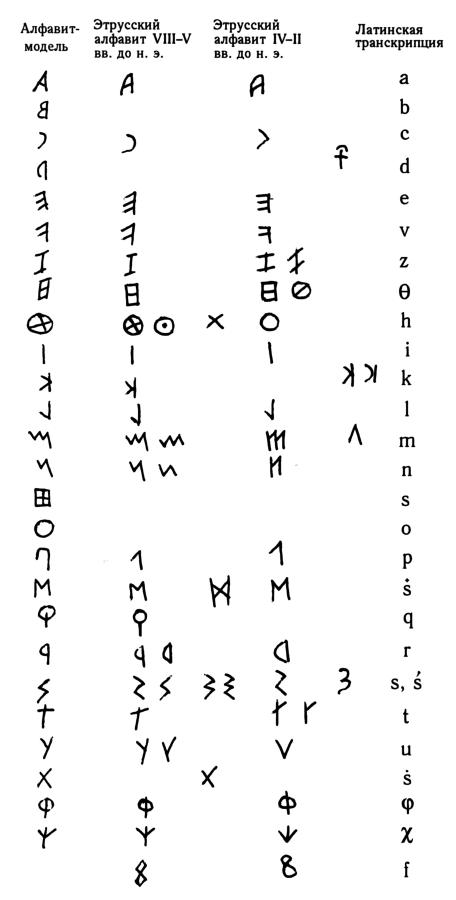

Thus, Volynskiy suggests a pattern of correspondence between the remaining Etruscan letters (including the complex ones) and the usual Cyrillic script. Let us also cite the table of Etruscan letters and their decipherments as used in modern Etruscan studies (fig. 15.8). We have taken it from A. I. Nemirovskiy’s book ([574]). The differences are enormous; also, the latter table has so far proved useless in the decipherment of Etruscan texts.

A. A. Neykhardt is forced to admit the following: “If we are to encapsulate the Etruscan mystery in just a few words, the first problem is one of their origin. The second, which is possibly even more serious, is the identity of their language, the language of numerous Etruscan scriptures and a vast body of epigraphic material accumulated over the years that Etruscan studies have existed as an academic discipline – so far an invaluable but, alas, useless array of materials available to every researcher. Isn’t that a pity!” ([106], page 218).

Y. Burian and B. Moukhova write the following, almost in unison with the previous author: “The heavy gate that guards the mystery of the Etruscans remains locked. The very appearance of the Etruscan statues that stare into nothingness contemplatively or appear immersed in meditation should be enough to convey that they have nothing to tell us. Etruscan writings are still silent, as though claiming that they won’t be read by anyone other than their creators, intending to remain silent forever” ([106], page 83).

We don’t want to play the part of judges in the dispute between the table of Volanskiy and the one used by the modern researchers of the Etruscan mystery. Our mission is different – we want to attract the attention of our contemporaries to the work of Volanskiy. It is possible that he has actually managed to find a key to the interpretation of Etruscan lettering. Our chronology might eliminate the obstacles that preclude us from perceiving his results as scientific.

12.3. The interpretation of Etruscan lettering according to Volanskiy.

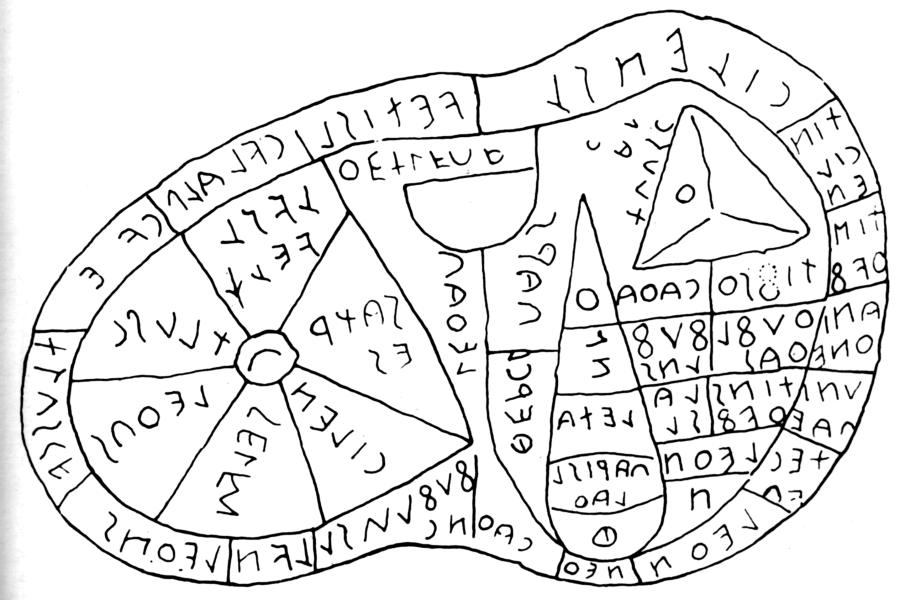

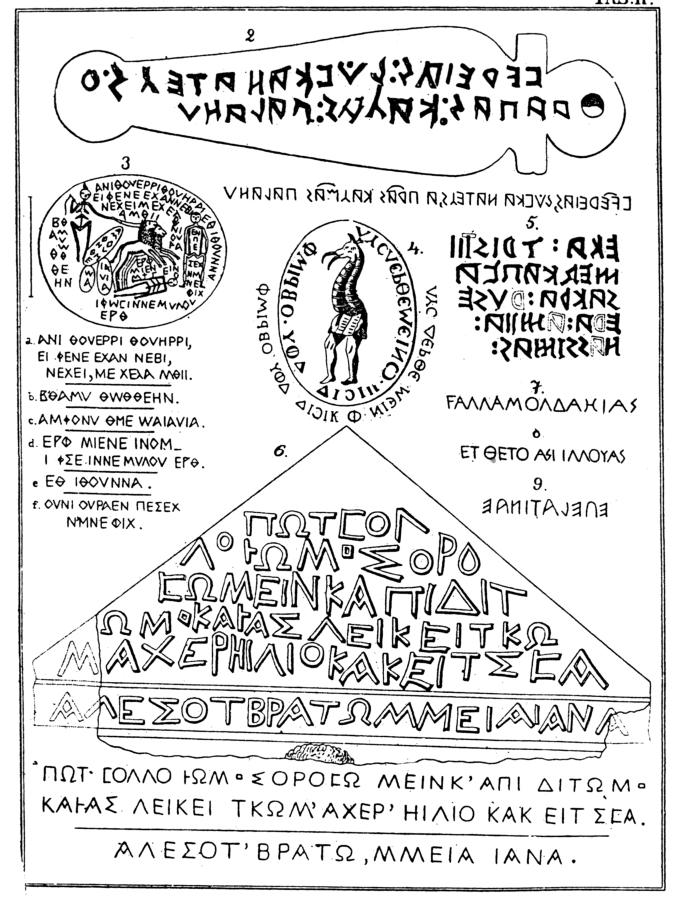

1) One needs to take an Etruscan text (such as can be seen in fig. 15.7 on the left).

2) Next we must change the Etruscan letters for their Cyrillic equivalents according to Volanskiy’s table (fig. 15.7, on the right).

3) The direction of writing has to be estimated – either could be used.

4) One can attempt to read the resulting text.

As would be the case with any other Old Russian (not Etruscan) text, it needs to be read several times thoughtfully, so as to decompose the text into individual words. The matter is that there were no gaps between words in many ancient texts; this complicates interpretation to some extent, but does not imply illegibility per se.

According to Volanskiy, the interpretation complexity of an Etruscan text (such as reproduced in fig. 15.7, for instance) is hardly that much higher than that of many Old Russian texts. We encounter certain words that we cannot understand in the Old Russian texts as well; however, most words are clear.

12.4. Volanskiy’s examples.

12.4.1. The headstone near Creccio.

Let us begin with the Etruscan text in fig. 15.7 on the left. Volanskiy writes:

<<The lettering from this most amazing headstone of all was copied by yours truly from the new publication of Theodore Mommsen’s book entitled “The Dialects of Lower Italy” . . . This headstone was found near Creccion in October 1846 . . . The humble publisher confesses that even at attempt to interpret this inscription would be a very bold one indeed>> ([388], page 75).

Therefore, here is the division of the authentic Etruscan text from fig. 15.7 into individual words as suggested by Volanskiy:

Etruscan original:

Reski ves Bog, vysh Vima i Dima, Yezmenyu Rasiyei,

Im-zhe opetse (moi) dom i detses, lepeyen Yezmen!

Yekatezin dalechim; do dolu zem poyezheyu;

Totsi vero-vero ies! kakoyem, Yenei tsar-rode.

Sideyiz s Ladoim v Yelishom, Leyti poymez, zabyvlayez;

Oi! dorogi, khoroshiy!

Translation suggested by Volanskiy:

All-father from Paradise, above Vim and Dim, you are the Yezmen of Russia.

Take care of my home and my children, greatest Yezmen!

Hekate’s domain is far away; I set forth to the end of the earth;

And, verily, this is so, just like Aeneas was my forefather.

Together with Lad in Elysium, you shall drink from the Lethe and forget.

O! Dear one, kind one!

Let us comment this translation. One cannot say that the entire text became crystal clear as a result – nevertheless, we have discovered some perfectly transparent Russian phrases that comprise more than one half of the inscription. At the same time, it is perfectly obvious that Volanskiy was strongly under the assumption that the text he saw had predated Christianity by a long time, and therefore couldn’t possibly contain any Christian expressions familiar to us from holy books.

We have therefore tried to edit Volanskiy’s translation somewhat, without fearing to find Christian elements in the Etruscan phrase. This is what we have come up with:

And thus said the Great Lord to Maidim, Yezmen and Russia,

He is also the guardian of my home and children. Fair Yezmen!

Yekatezin is far away; I set forth towards the edge of the earth [possibly, a reference to the dead man’s voyage into the kingdom of the dead].

Only faith – the faith of Czar Yenei [or Menei?]

Sitting with Lad and Elisha [or Elijah].

Do you remember, or do you forget?

Oh, dear one, kind one!

We see a perfectly comprehensible old Russian text, clear for the most part. We see references to unfamiliar names (Maidim, Yezmen etc); possibly, ancient names of some Italian provinces. Russia is mentioned openly – as “Rasia”, a form common for the Southern Slavs. Let us reiterate that Old Russian texts also occasionally fail to get deciphered completely, to the very last word. However, if the Etruscan text contains whole phrases that can be read clearly, one gets the impression that the language was chosen correctly, at the very least.

12.4.2. Boy with a goose.

See fig. 15.9. Volanskiy writes: “The figurine . . . represents a naked Get boy carrying a goose. It was found in Tuscany in 1746 . . . Jansen published it as number 33 in his collection of Etruscan inscriptions. For 100 years . . . there was much talk about this figurine, but nobody has suggested a valid interpretation so far” ([388], page 184). The figurine is located on the boy’s right foot, and reads as follows (qv in fig. 15.10).

The Etruscan original:

Byelo gas veya nagnala; do voli dase Alpanu;

Penate! golen Geta tudi nes tole nadeis.

Translation:

The wind caught up with the white goose, surrendered itself willingly to Alpan;

Behold! Geta went there naked, just hoping.

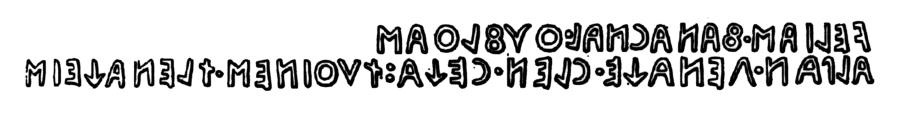

12.4.3. Boy with a bird.

See fig. 15.11. Volanskiy reports: “This famous bronze figure, which has been known to us for over two centuries and a half, was found in 1587; there were many copies and interpretations of it, but no real explanation has been made to date . . . Dumpster represents it in table XLV, and Gori, in table III, #2” ([388], page 99). The lettering can be found on the leg of the boy, qv in fig. 15.11.

In Etruscan:

Vole dae; mozhe cho za ni milek chaet.

Translation:

I’m giving leave; maybe the dear one awaits something.

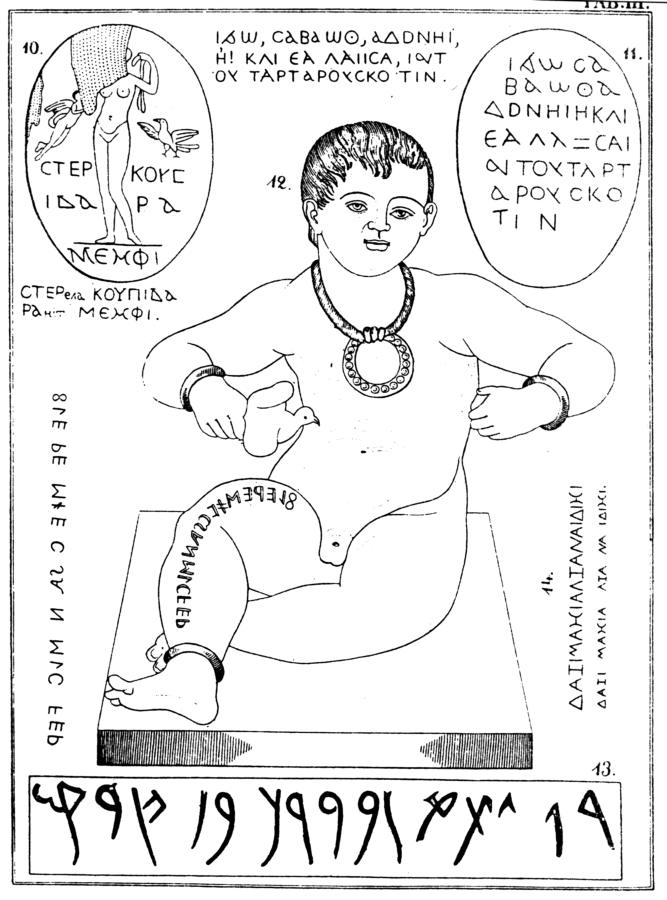

12.4.4. Double-sided cameo.

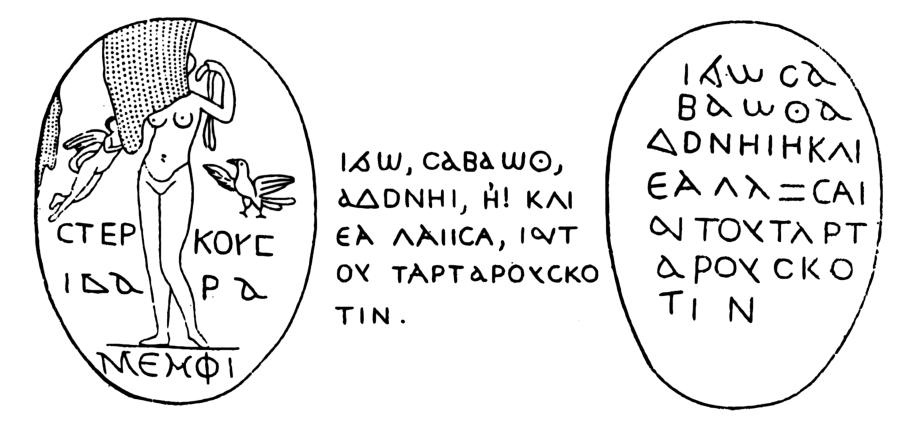

See fig.15.12. Volanskiy writes: “Ulrich Friedrich Kopp reproduces this cameo in his work entitled ‘De varia ratione Inscriptiones interpretandi obscuras” (1827) . . . on the title page . . . without a single comment about its content . . . The front side [fig. 15.12 – left side – Auth.] . . . depicts the naked nymph Menithea . . . and Cupid flying towards her . . . The three lines of text set in the ancient Slavic, or Greek alphabet, the difference being of no importance here, tell us the following” ([388], page 97).

In Etruscan:

Sterela Kupida ranit Menifei.

Translation:

Cupid’s arrow wounds Menithea.

“The reverse [fig. 15.12 – right side – Auth.] is an inscription in Russian – seven lines of texts that can be read as follows” ([388], page 97).

In Etruscan:

Yao, Savaof, Adonei. Yei! koli yega layitsya, idut v tartaroiskotinu.

Translated:

I, Shabuoth Adonai. Yea! Those who speak ill of him roll to Tartarus, the swine.

In this particular case our interpretation of the inscription is somewhat different from that suggested by Volanskiy.

We shall stop with citing examples, referring the reader to [388] for more.

12.5. The unspoken taboo to interpret Etruscan inscriptions with the aid of Slavonic languages.

Before we stop discussing the Etruscan topic, we must make a comment about the last inscription on the cameo. How is it humanly possible to leave it unnoticed for so many years? It is written in regular Cyrillic script, after all, and from left to right to boot. What could have prevented the learned historians from deciphering the text?

We believe the explanation to be as follows: deliberate reluctance. Why would that be? Our reconstruction provides an answer to that question.

It appears that the West Europeans have done much work in order to wipe out all possible traces of the fact that the Great = “Mongolian” conquest of the XIV century and the Ottoman = Ataman conquest of the XV-XVI century were in fact Russian and Russo-Turkic. After the Reformation, in the XVII-XVIII, an unspoken taboo was introduced on mentioning the former Slavic presence in the Western Europe in any way at all. One of the consequences was the de facto ban on every attempt to use Slavic languages for the interpretation of the so-called “illegible” inscriptions found in the Western Europe.

The fate of F. Volanskiy was far from easy. Apparently, he wasn’t forgiven for his scientific research concerning the history of the Slavs in the Western Europe. This is what we know about him:

“We cannot remain silent about the achievements of Faddey Volanskiy. He was the one to find the ‘Song of the Defeat of Judean Khazaria by Svyatoslav the Brave’ in 1847 . . . The Jesuits made a pyre . . . of his books . . . this is what the Polish Jesuits were like in 1847” ([496], pages 277-278). However, Nikolai I vetoed the actual execution of F. Volanskiy, despite the demands of the Jesuits.

12.6. A fresh view of the Russian history stemming from our new understanding of the history of the Etruscans.

A new understanding of the Etruscan history might lead us to a new conception of the history of Russia in the XIV-XVI century. Ever since the XVII century, we have been persistently fed the misconception that Russian culture before the XVII century was inferior to the culture of the Western Europe – and even more so after the XVII century. Therefore, let us withhold from trying to grasp every facet of Etruscan life (or, as we are beginning to realise, the life of the Slavic and Turkic peoples in the Western Europe) and concentrate on the Etruscan achievements in art, medicine etc. It turns out that they made great advances in those fields. We have already used the words of Diodorus of Sicily as an epigraph to the present chapter, where he mentions their tremendous achievements in science, culture and military art. Many of the “ancient” authors wrote about it as well.

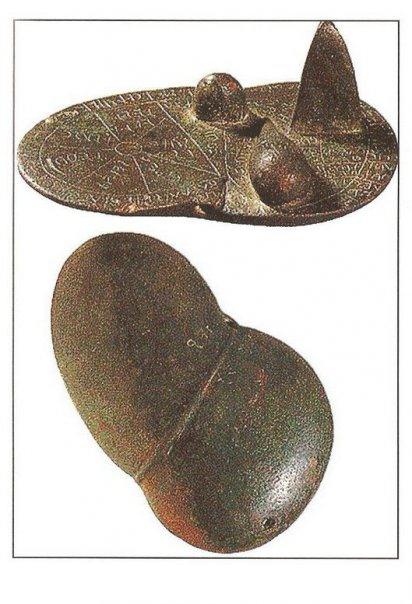

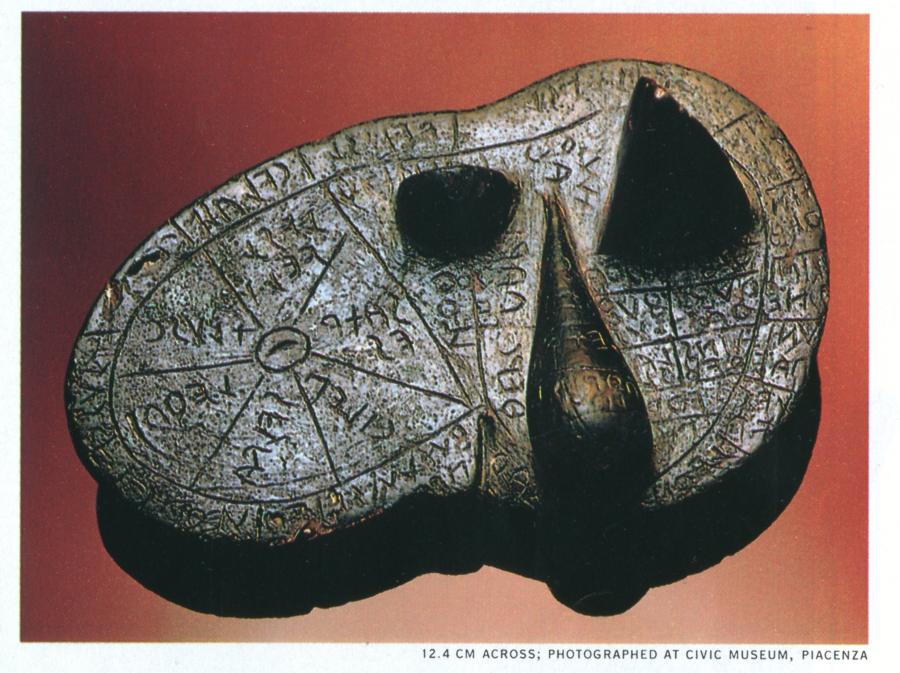

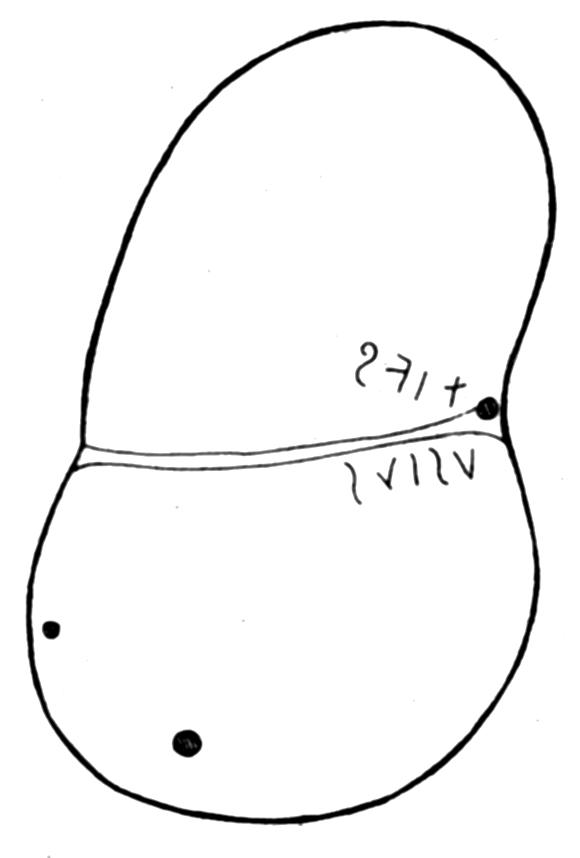

In fig. 15.13 we see an Etruscan model of liver made on bronze. Drawn copies of its front and rear side can be seen in fig. 15.14 and 15.15.

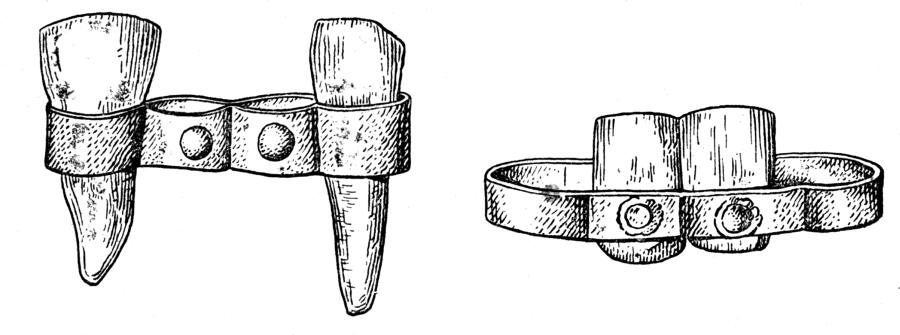

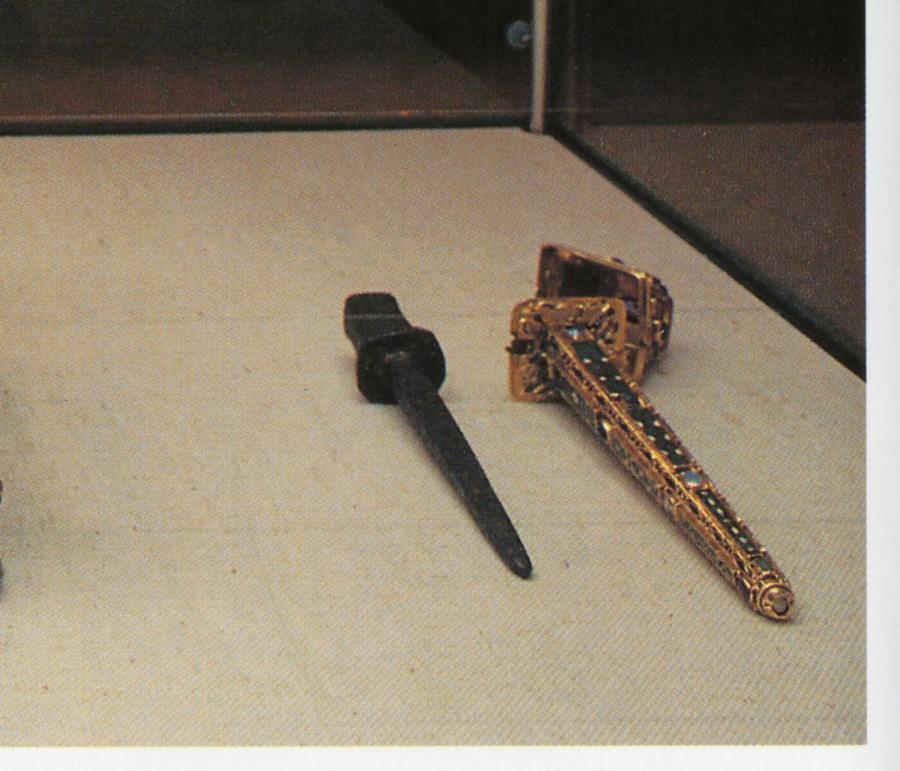

In fig. 15.16 we see prosthetic teeth made by the Etruscan, which speaks volumes about their knowledge of medicine.

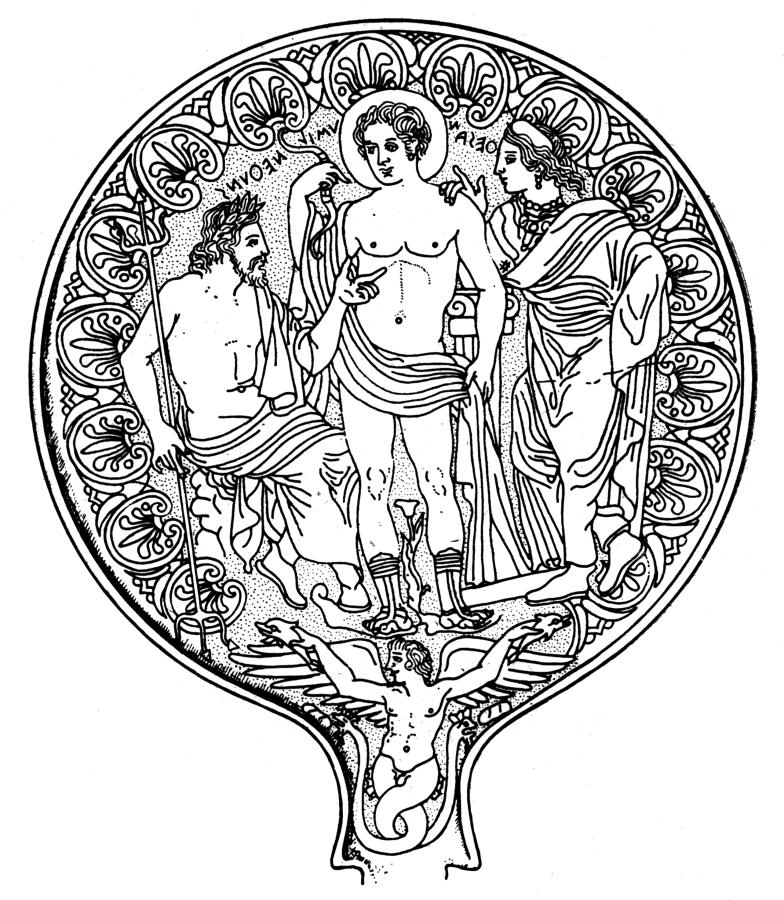

In fig. 15.17 we see the so-called “scene of hammering in the nail” from an “ancient” bronze Etruscan mirror, presumably dating from 320 B. C. However, this interpretation of the scene as suggested by historians appears incomplete and strange, since they fail to mention just what they mean by that. The Etruscan artists are unlikely to have depicted a winged angel building a wooden construction or a church with the use of hammer and nails. The motif is likely to be Evangelical – it is possible that the angel isn’t driving the nail in, but rather removing it from the body of Jesus Christ in order to take him off the cross. Let us remind the reader that Jesus is said to have been nailed to the cross; the nails were removed and kept as Christian halidoms. One such nail is still kept in the Trier Cathedral in Germany (see fig. 15.18). Therefore, it is perfectly natural that a famous Christian motif should be pictured on one of the luxurious “ancient” Etruscan mirrors.

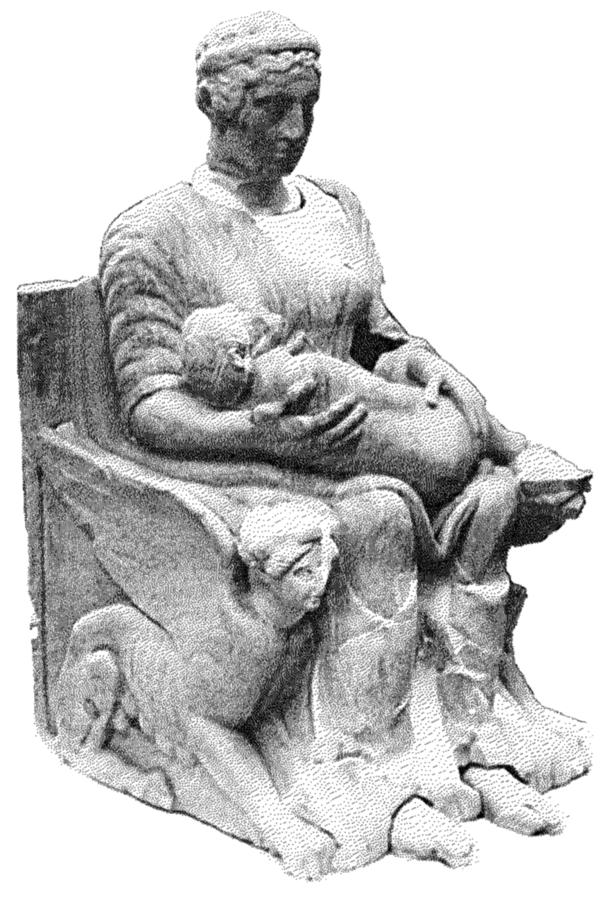

In fig. 15.19 we see another Etruscan bronze mirror. It may also depict a Christian motif – Our Lady with infant Jesus. In fig. 15.20 we see a photograph of an ancient Etruscan statue in Florence; one cannot quite escape the impression that it portrays Our Lady with the child as well. This definitely contradicts Scaligerian chronology, but is perfectly normal from our reconstruction’s point of view

Another Etruscan mirror can be seen in fig. 15.21 – it is presumed to date from the III century B. C. This mirror was used by Etruscan women – or Russian women, as we realise today. Apparently, the Etruscans were in fact the Russian population of Italy in the XIV-XVI century A. D. They built houses, fought in wars and raised children. A propos, they portrayed themselves in the exact same manner as we consider characteristic for the “ancient Greeks and Romans”. Laurelled heads, loose southern attire and so on. Actually, in the bottom we see a youth with wings that holds two fishes in his hands – it is as though he was portrayed against the background of a bicephalous imperial eagle, or the Christian cross.

Let us reiterate that all such artwork is confidently classified as “Graeco-Roman” nowadays. This is true in general – however, it has to be stated that the style in question is really the Old Russian style declared “ancient” and “Graeco-Roman” in the XVII-XVIII century, and presumably completely unrelated to the mediaeval Russia, or the Horde, and erased from the history of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire of the XIV-XVI century by force. The Empire itself was cast into deep antiquity and proudly called the “ancient” Roman Empire. The Empire was dyed into new colours, but its “ancient” phantom reflection has retained all of its glory, while the history of the original – Russia, or the Horde, was immersed into obscurity and the darkness of ignorance.

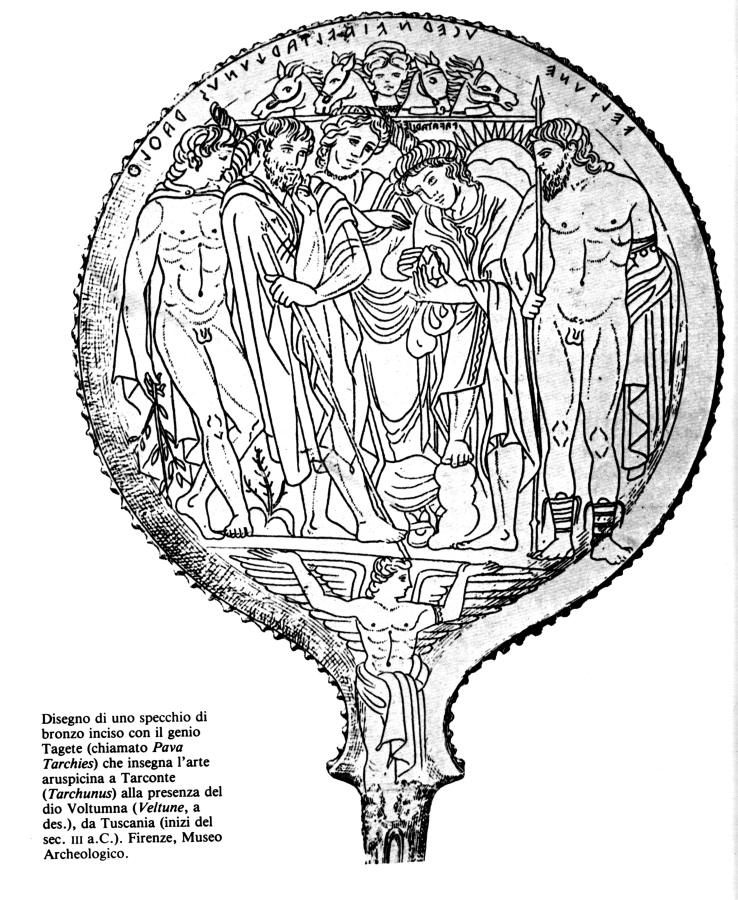

It is common knowledge that divination was very popular in Russia. In fig. 15.22 we see an Etruscan mirror that depicts the divination rite – we apparently see Russian men and women of the XIV-XVI century who try to foretell their future; yet it is doubtful that they could predict the fact that some 100-200 years later their history would be transplanted from the XIV-XVI century into distant past and attributed to a completely different nation.

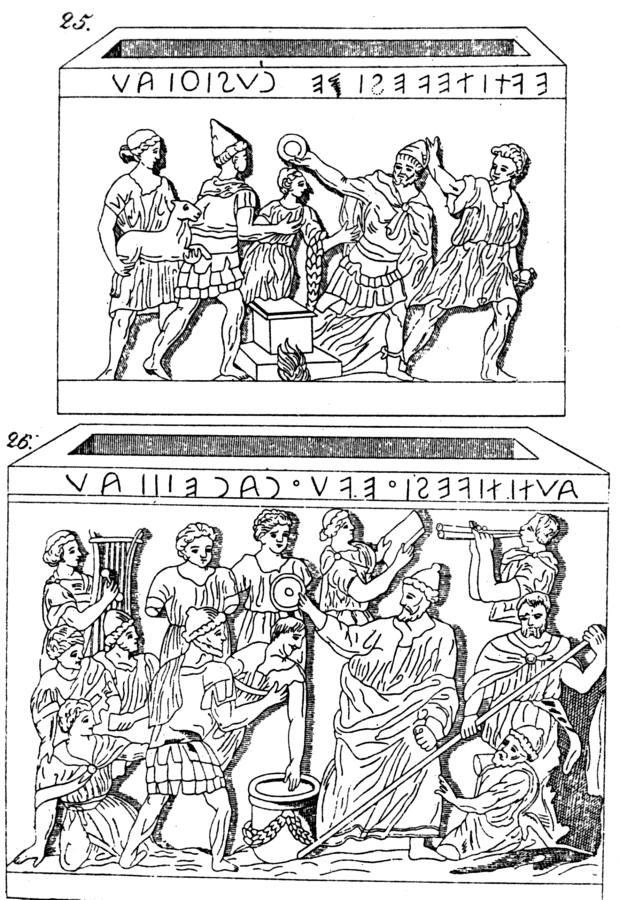

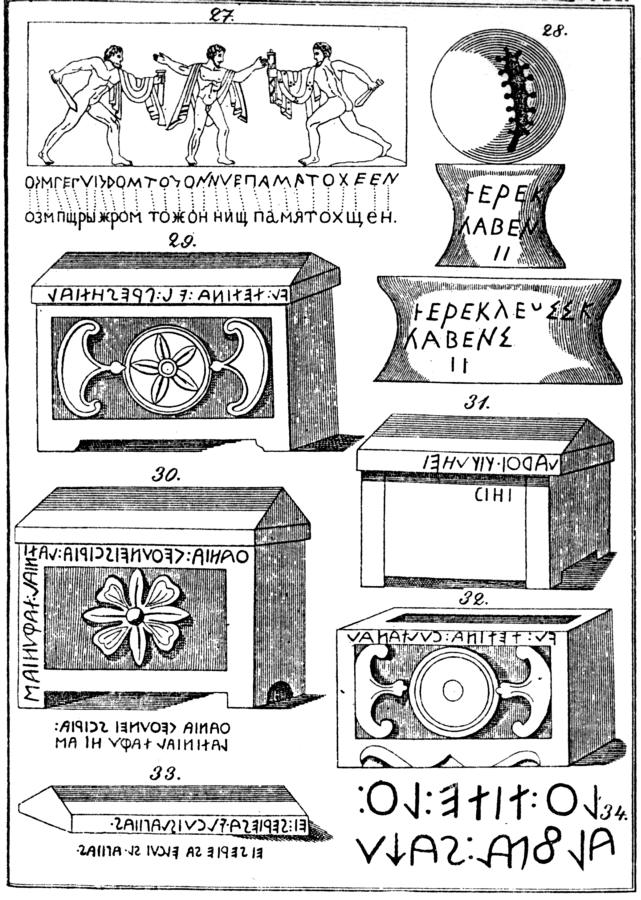

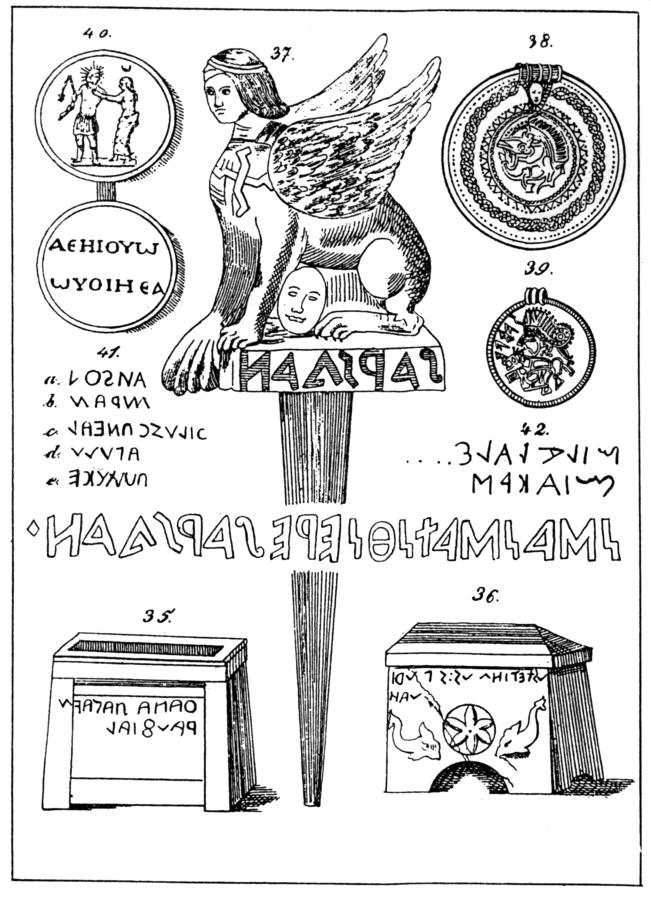

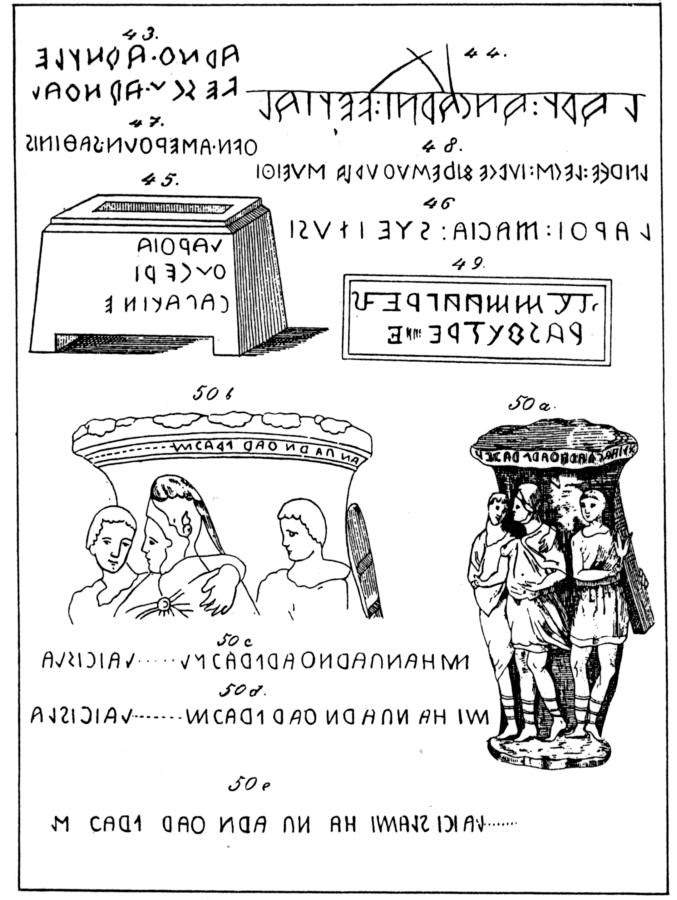

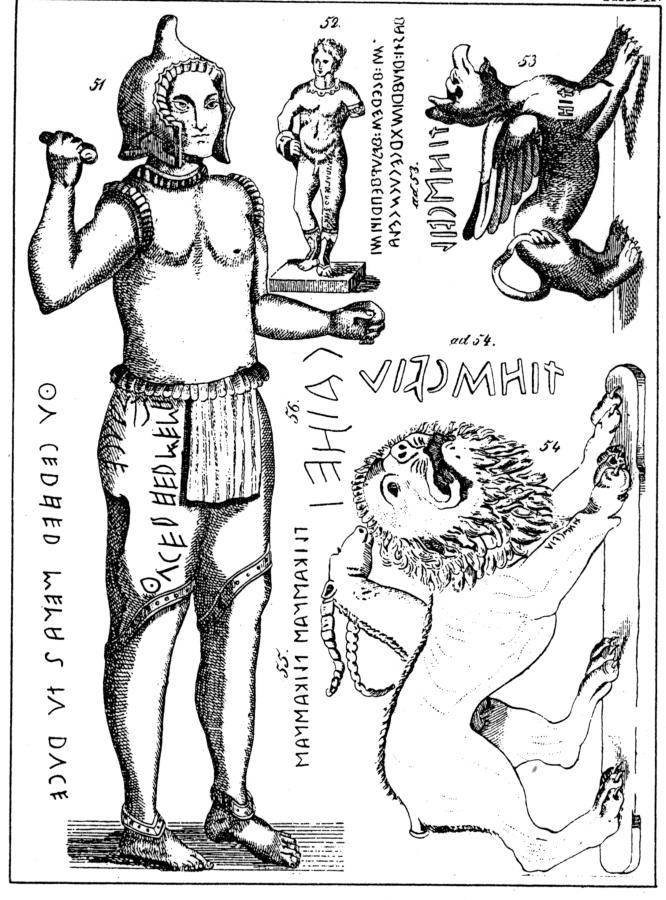

In figs. 15.23, 15.24, 15.25, 15.26, 15.27, 15.28, 15.29 and 15.30 we see some of the Etruscan inscriptions collected by F. Volanskiy in [388].

Let us conclude with the reproduction of the famous Etruscan bronze statue of the horrifying Chimera (fig. 15.31). It is presumed to date from the IV century A. D. Such artwork must have symbolised the Great = “Mongolian” conquest, likewise the lugubrious head of Gorgon Medusa with its serpentine hair.

13. Slavic archaeology in the Western Europe.

In 1996 the famous Russian artist I. S. Glazunov, Academician of Fine Arts, published a book entitled “Russia Crucified” ([168]). It has an interesting section dedicated to the more obscure facets of Slavic archaeology. The main corollary of I. S. Glazunov can be encapsulated as follows: a tremendous amount of details pertaining to Slavic archaeology remains concealed from the public and even from the scientist – apparently, this is being done deliberately. Our research explains just why this happens. Archaeology very often contradicts Scaligerian history; this is especially manifest in cases when archaeological findings happen to be Slavic. Thus, Slavic archaeology and the inevitable conclusions drawn on its basis remain a forbidden topic in history. This has been happening for many years on end.

I. S. Glazunov draws the reader’s attention to the almost forgotten works of Vassily Markovich Florinskiy, a distinguished Russian scientist of the XIX century and the founder of the Tomsk University. I. S. Glazunov writes:

“Vassily Florinskiy (1834-1899) lived for 65 years. He graduated from the St. Petersburg Academy of Medicine and Surgery. The outstanding abilities of the graduate were duly noted, and he was made Professor in a couple of years. However, the name of this man has been made immortal for other reasons than his achievements in the field of medicine. His ultimate passion was archaeology, which became his destiny. Comparative archaeology, to be more precise.

The eminent scientist had searched the answer to the poignant question concerning the ethnical and racial identity of the makers of thousands ancient burial mounds scattered all across the vastness of Siberia, and he found it. Florinskiy’s answer was clear and unambiguous – the ancient populace of Siberia belonged to the Arian race; more specifically, to the tribes that later became known as Slavic. Vassiliy Markovich conducted an enormous body of work in comparing the archaeological findings from Schliemann’s Troy and the ones related to Adriatic Venetes (known as a Slavic nation – neither Russian historians nor their colleagues from the West dare to deny this fact), as well as the Baltic Venetes, to the findings from the burial mounds of Northern and Southern Russia. The similarity between the artefacts found in the lands of the Venetes, or, rather, the Slavs, and those from the Siberian burial mounds, turned out so striking that every shadow of doubt was swept away” ([168], #8, page 211).

And so we learn that Asia Minor, as well as a significant part of the Western Europe, were formerly populated by the same Slavic nation as Russia and Siberia. It is perfectly obvious why – this was a result of the Great = “Mongolian” conquest of Eurasia, which, as we have demonstrated above, took place in the XIV century and was predominantly Slavic and Turkic.

Now let us consider Troy. It is wrong to assume that the settlement discovered by Schliemann was the actual ancient Troy. As we demonstrate in CHRON1 and CHRON2, the “ancient” Troy was but an alias of Czar-Grad, or Constantinople. However, this is of little importance to us presently – we are concerned with the fact that there were Slavs among the “ancient” Trojans.

Another quote from I. S. Glazunov: “Florinskiy writes that the Adriatic or Italian Slavs – namely, the Venetes, members of the Trojan tribe union, founded . . . Venice and also Patava (from the Slavic word ‘pta’ – ‘bird’; the city is known as Padua today) upon leaving Troy” ([168], #8, page 211).

A propos, we know that Venice is supported by ancient wooden piles, which are several centuries old. One may well enquire about the wood they were made of – according to some sources, it is Siberian larch, which does not rot in water. If this is indeed so, the next logical question is of even greater interest – what was the connexion between the founders of Venice and Siberia? The very existence of any such link is an absurdity in Scaligerian chronology; the research of Florinskiy and our reconstruction make it perfectly natural. Unfortunately, we haven’t found any references to the nature of wood used for the piles that support Venice in any literary source; it would be interesting to study this issue further.

I. S. Glazunov tells us further: “I recollect my sojourn in Germany, GDR to be more precise, where I worked on the incarnation of scenic images of ‘Prince Igor’ and ‘The Queen of Spades’ – I had a great yearning to see the famed Rugen Island, the former location of the glorious Arcona – an ancient religious centre; a Mecca of our ancestors, the Baltic Slavs, if you will. Soviet history textbooks, likewise our scientists, must have had reasons of their own to forget the millenarian history of our ancestors on the shores of the Baltic Sea” ([168], #8, page 213).

We have the following to add. Our research makes it understandable why historians and archaeologists are indeed reluctant to mention the former presence of the Slavs in the Western Europe, Asia Minor, Africa etc. Although historians have convinced everybody of the “great antiquity” that the Slavic presence should presumably date from, some of them appear to realise that all the extra age was added in a perfectly arbitrary fashion and that many of the Slavic findings made in Europe are in fact mediaeval. This is why archaeologists prefer to avoid touching this sore spot of Scaligerian history.

I. S. Glazunov: “When I visited the Isle of Rugen, I found out about the archaeological excavations conducted there and hurried to get acquainted with the young archaeologists who studied at the Berlin University . . . One of them . . . shook his head in dismay and said: ‘Such a pity about your being too late!’ . . .

‘Too late?’ – I asked in astonishment. ‘How come?’ The young man replied that a wooden vessel of the IX century [in Scaligerian dating, of course – Auth.] was unearthed several days ago, but buried in earth again, since nobody needed it. ‘But how? . . . Why did you do it?’ . . . The young archaeologist answered evasively: ‘Who needs it?’ – ‘What do you mean?’ – I could not shake off the amazement. ‘You could have sent it to Moscow, after all!’ The young German looked at me with his grey eyes of a Viking and then cast his glance aside. ‘Moscow isn’t interested’. ‘But really, for God’s sake, we have Academician Rybakov, the famous historian and archaeologist’. A frown appeared on the Viking’s tanned forehead. ‘We know the name of Genosse Rybakov from our leader, Genosse Hermann. Our business is to dig and to report our findings to the professor’. Being in a state of deep shock, I asked my new acquaintance about the most interesting findings made by the German expedition. The son of the Teutonic race shrugged and uttered the following phrase in irritation, which became recorded in my memory forever: ‘Everything is Slavic here down to the very magma!’” ([168], #8, pages 214-215).

The remnants of the initial Slavic populace still live in Germany and are known as the Sorbs. “Sorbian is one of the Western Slavic languages spoken by the Sorbs residing in the region of Dresden and Kotbuss (GDR). Spoken by some 1.000.000 people” ([485], page 277).

I. S. Glazunov tells us further about his conversation with the assistant of Professor Hermann in Berlin, who informed him of the following: “The only thing I can say to you is that we have an enormous archive here in GDR, stuffed with the Slavic archaeological artefacts and ancient books written in Church Slavonic. We have taken a great many things to this archive, and nobody has sorted through it so far” ([168], #8, page 215).

Glazunov’s question about whether the archive also contained Slavic books written on planks of wood was answered as follows: “There might be some . . . however, none of our scientists have expressed any interest in such matters, nor did any of your Soviet ones” ([168], #8, page 215). One wonders about the fate of this “Slavic archaeological archive” – could it have burned down “purely accidentally”?

As we have already mentioned, it appears to be hard to date any of the Slavic archaeological findings made in Germany to deepest antiquity, since the remains of the Slavic populace live in Germany to this very day. I. S. Glazunov quotes the words of “the writer and publicist Dmitriy Anatolyevich Zhukov, known for his interest in the Russian and ancient Slavic culture” addressed to him: “Have you by any chance . . . visited any of the Sorbs, the last Slavic tribe resident in the Western Europe? . . . All that has remained from the Slavs in Germany is the tiny tribe of the Sorbs; however, they aren’t mistreated by anyone in the GDR in any way at all”. The word “Sorbs” appears to be a slight modification of the word “Serbs”.

Another remark is as follows. Certain scientists are trying to rationalise the fact that the same old Slavic objects are found all across Eurasia. They attempt to find a place in Scaligerian chronology where this vast body of Slavic materials can be placed. However, since there’s no “free space” anywhere in the Middle Ages, they are forced to go deep into the past and invent theories about the mythical “ancient proto-Slavs”. We are of the opinion that all such findings are completely unrelated to the “ancient proto-Slavs”, which did naturally exist at some point, although we know nothing about them. They pertain to the mediaeval Slavic “Mongols”, or “Great Ones”. They were the conquerors of Europe and North Africa in the XIV century, and they also conquered the Americas in the XV century, qv in CHRON6.