Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 16.

History and chronology of the “ancient” Egypt. A general overview.

6. The religious character of many “ancient” Egyptian monuments.

Chantepie de la Saussaye reports the following: “Most of the surviving monuments with lettering found upon them . . . are of a religious nature. About nine tenths of the papyri that have reached our day are clearly religious in content . . . All this material is rather homogeneous, and owes its existence to the existing funereal rites almost exclusively” ([965], page 101).

It is likely that Egypt was one of the primary religious centres in the X-XIII century Byzantium as well as the Great “Mongolian” Empire of the XIV-XVI century. The cult of the dead was concentrated here. It might be that the custom was introduced after the observation that a corpse does not rot in hot sand, and so the hot and dry climate made these places most suitable for burials.

Traces of the ancient custom to bury corpses in the sand still existed in the epoch of the pyramid construction, when the aristocracy was already buried inside sepulchres. For instance, the spells of the funereal “Pyramid texts” report the rite of “removing the sand from one’s face – clearly an anachronism in the times when the pharaohs had long been buried inside pyramids” ([464], page 15).

This may explain the domination of funereal themes in many of the Egyptian artefacts.

The Bible often mentions the mysterious city of Eir-Dud, whose name usually translates as the “City of David”. N. A. Morozov collected all the Biblical references to this city and discovered that nearly in every case it is mentioned as the burial ground of the Judaic, or Theocratic kings. Considering the dynastic parallelisms that we have discovered (see CHRON1 – CHRON2), they are likely to identify as follows:

Byzantine rulers of the X-XIII century,

The Great = “Mongolian” Princes, or Khans, of the XIV-XVI century,

Ottoman Sultans (or Atamans) of the XIV-XVII century,

The Mameluke, or Cossack rulers of the XIII-XVII century.

It is most likely that the Biblical “City of David” wasn’t an actual place of residence, but rather a huge necropolis – the royal cemetery, or City of the Dead. If we are to follow the statistical dynastic parallelisms, qv in CHRON1 – CHRON2, among the rulers buried in this necropolis we find the following “ancient” figures: Diocletian, Constantine I, Constance I Chlorus, Julius Caesar, Pompey, Theodosius I the Great and so on. Incidentally, the sepulchres of these rulers are considered lost in Scaligerian history. It isn’t even known just where they may have been buried.

One must assume that the closest relations of the rulers were also buried there – the royal kin, highest ranking state officials, ecclesiastical hierarchs and so on.

Therefore, we have to find a large funereal complex in the Mediterranean region. Such a necropolis does actually exist, and it only exists in a single country – the famous pyramid field in Gizah and the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, Egypt.

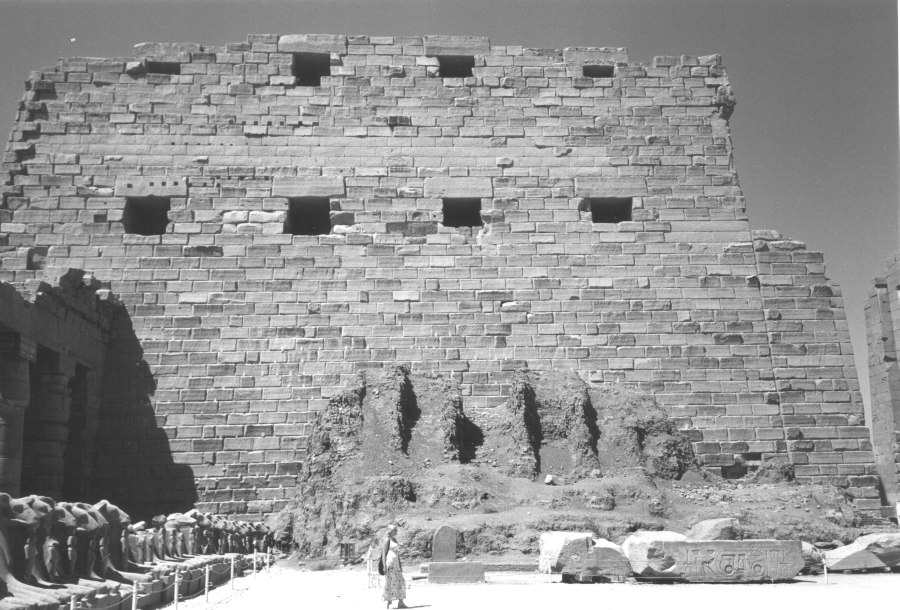

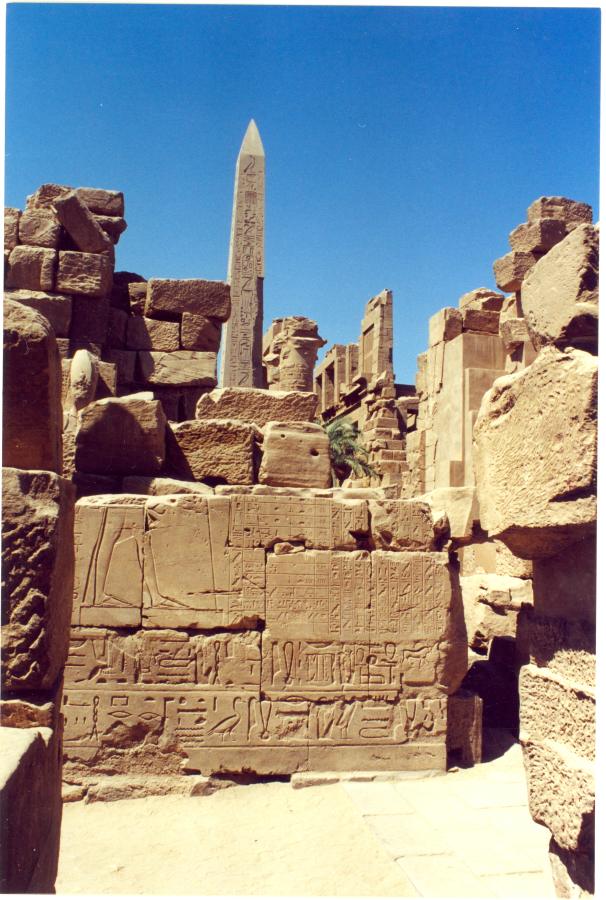

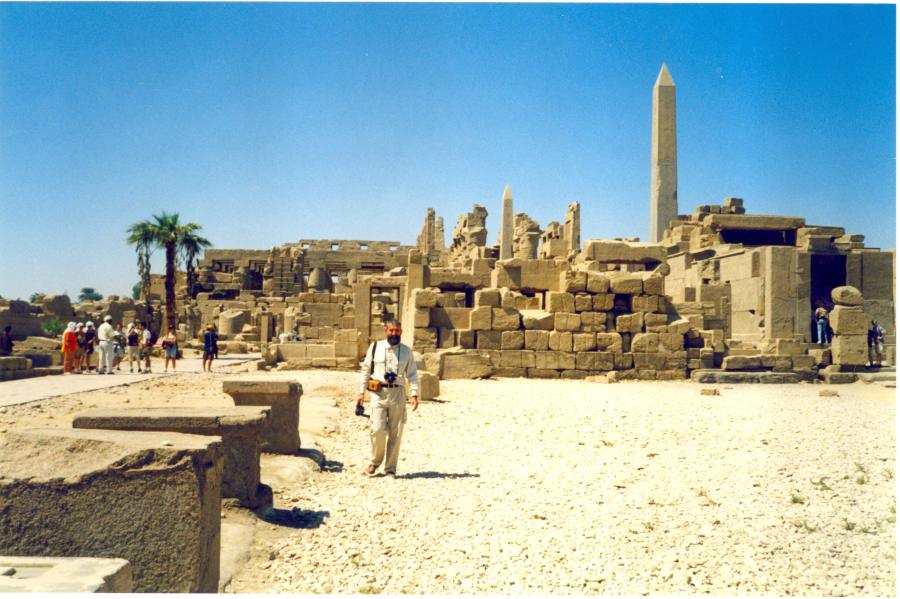

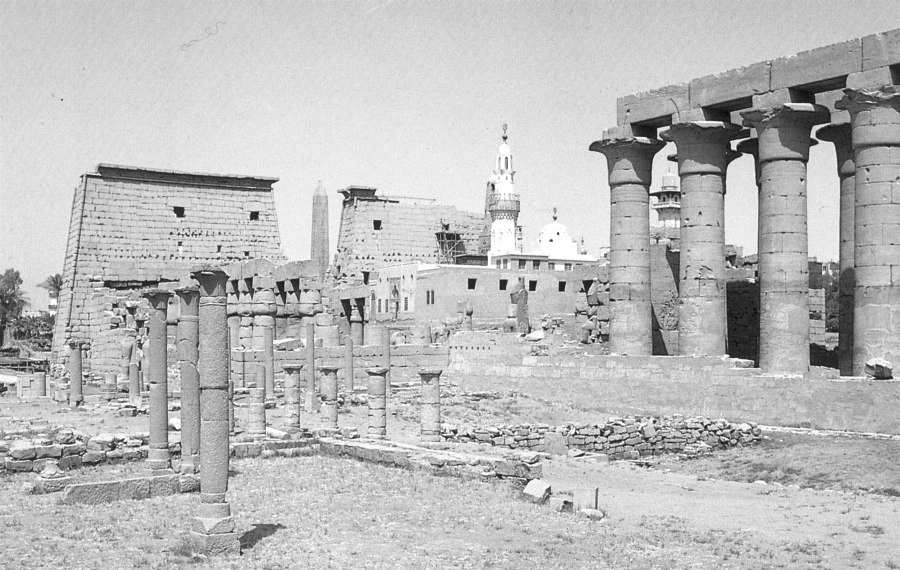

Let us remind the reader that there is an enormous royal cemetery in Egypt – the so-called “Valley of Kings”. It is a large territory covered by hills of soft stone. Many of the royal sepulchres were discovered in the valleys between these hills, including the famous grave of Tutankhamen. The entire valley is located inside the gigantic bight of the Nile. On the Eastern bank of the Nile we find the City of Luxor, whose name might stand for “luka tsarei” (“Bight of the Czars”), with its two enormous “ancient” Egyptian constructions – the temples of Karnak and Luxor (see fig. 16.31). Both temples, or fortresses, as well as the famous colossi of Memnon that stand on the Western bank of the Nile and appear to guard the passage to the Valley of the Kings in a way, appear to comprise a single grandiose funereal complex with the vast royal cemetery in the hills of the Nile Bight. The same complex must also include a number of temples found in these parts, among them – the famous Temple of Dendera located in the actual Bight of the Czars, or Luxor, on the Western bank of the Nile.

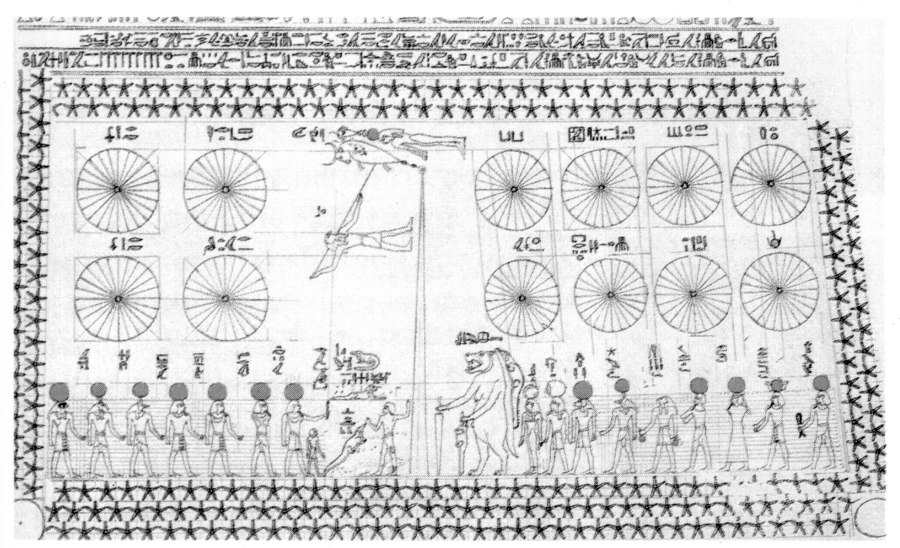

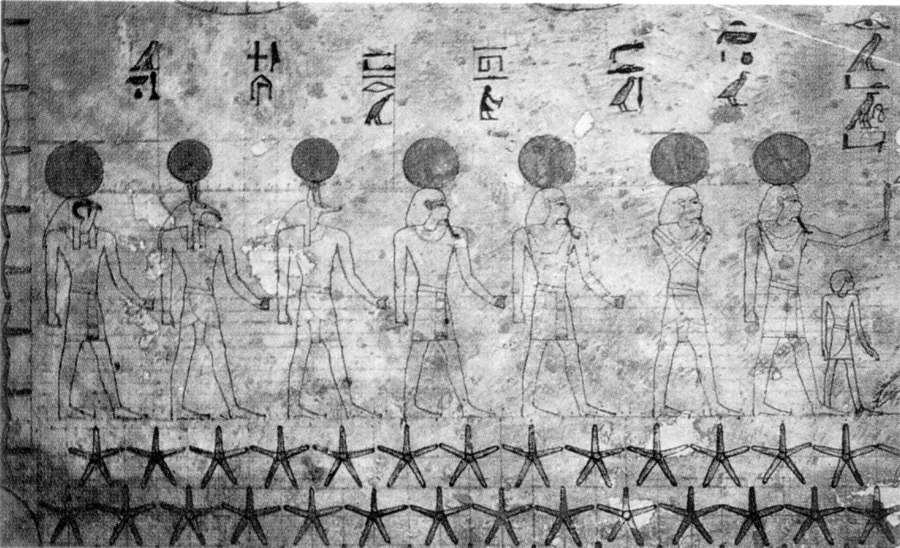

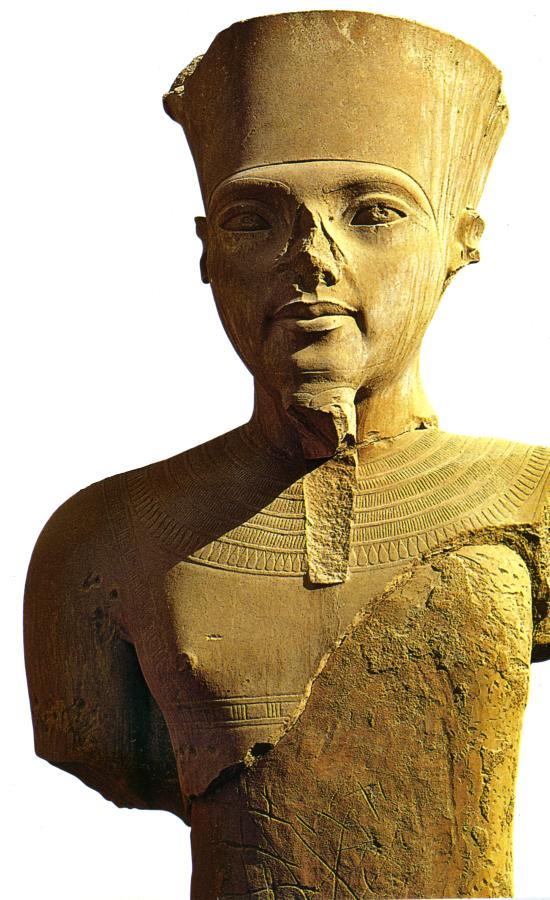

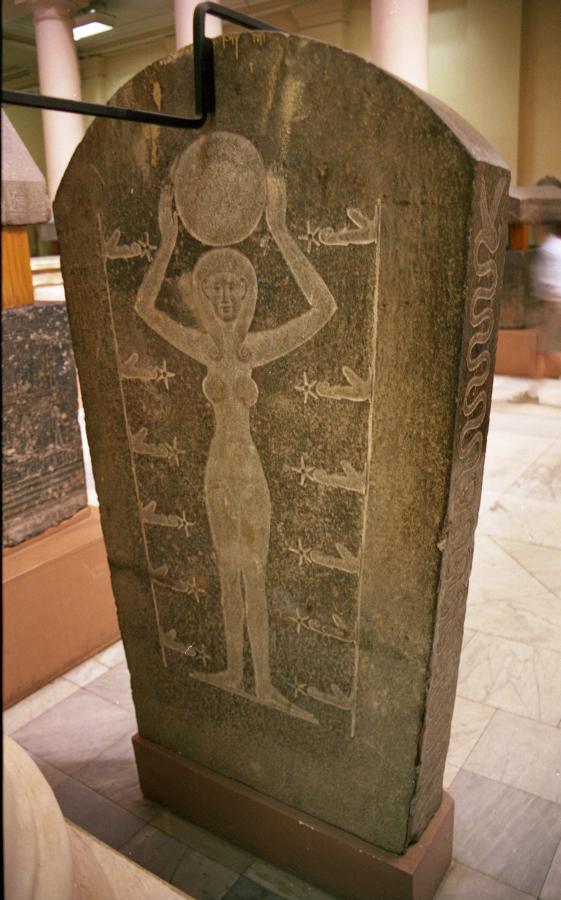

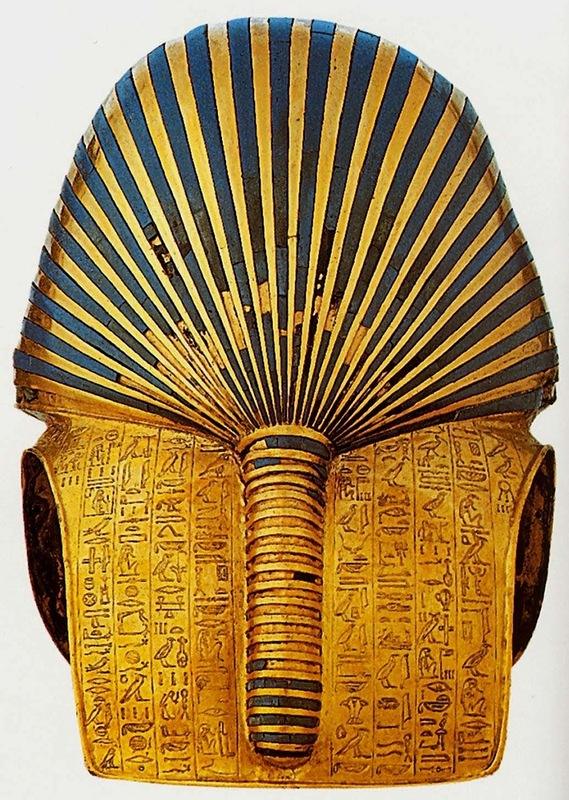

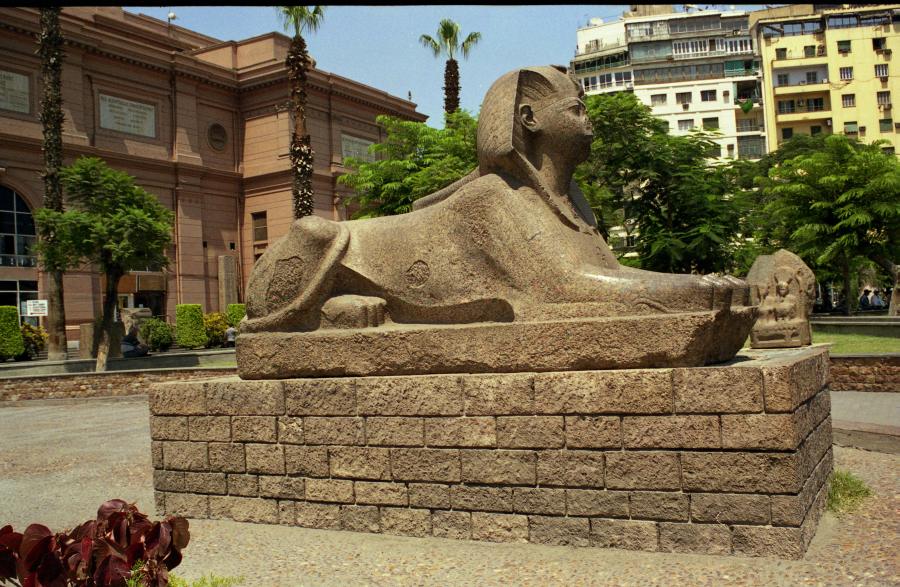

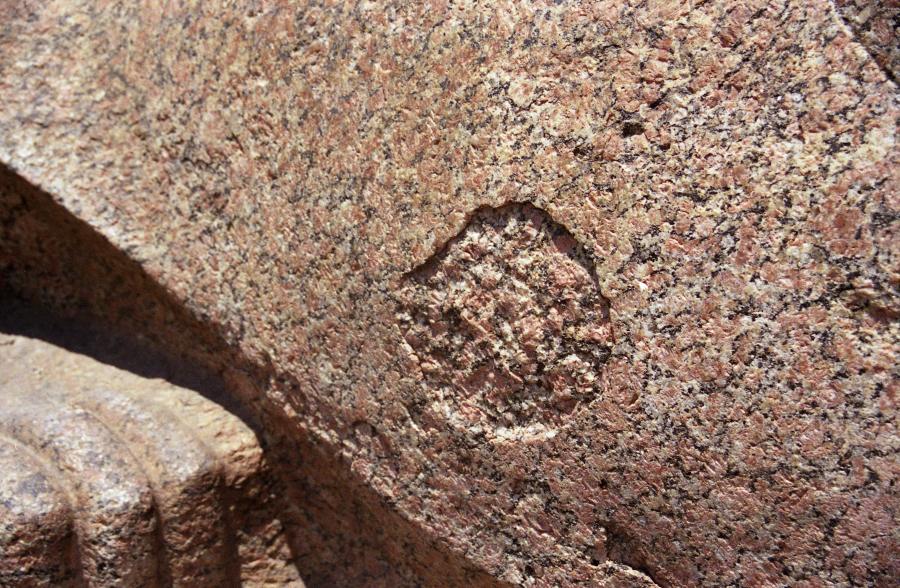

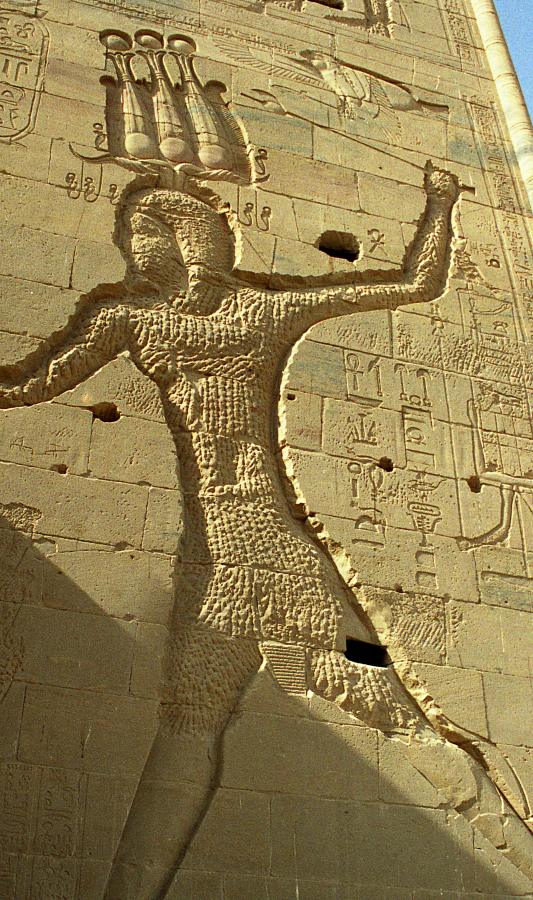

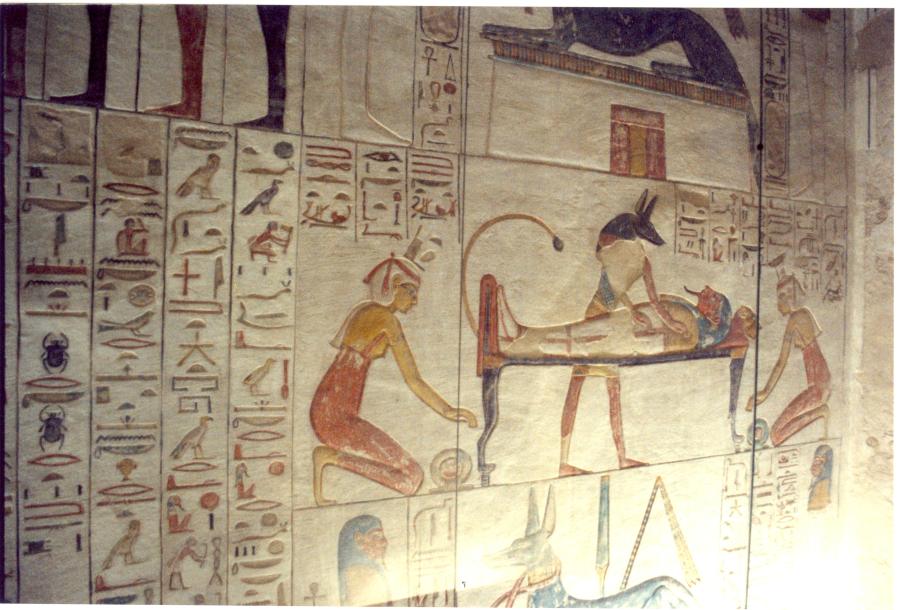

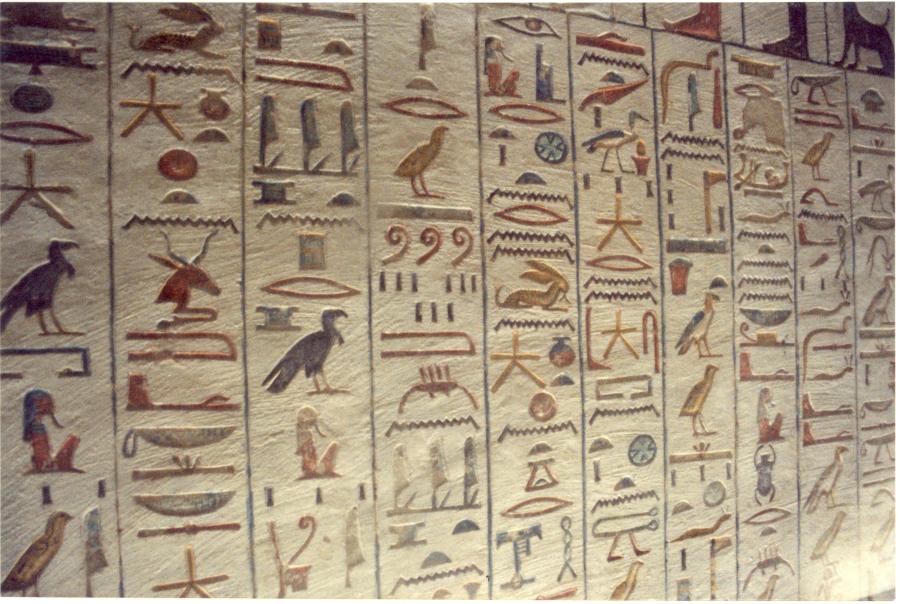

Some of the interesting motifs found among the local artwork can be seen in figs. 16.32, 16.33, 16.34, 16.35a, 16.35b, 16.36, 16.37, 16.38, 16.39 and 16.40.

Judging by the artwork found on the walls of the Karnak Temple ([499], page 10), the body of a deceased king would first be delivered to the Temple of Karnak via the Nile, which is close to the Eastern bank of the river. Then the dead ruler would be transported along the road paved in stone parallel to the Nile known as the Sphinx Alley – some 3.5 kilometres long. The alley connects the Karnak Temple with the Luxor Temple, which is already found on the very bank of the Nile. The funereal procession would then return to the Temple of Karnak, and the body of the king would be secretly taken across the Nile a few days later, past the Colossi of Memnon to the valleys of the necropolis hidden among the hills of Luxor, or the Bight of the Czars.

A large sepulchral cave would be carved in the side of a hill, with the sarcophagus containing the mummy placed therein. The walls were then covered in frescoes (see figs. 16.41 and 16.42). Many of these caves have been found and opened for the tourists. The entrances to the sepulchres were blocked so as to be completely inconspicuous from the outside. After the dissolution of the Empire, nearly all of the sepulchres were robbed. It is also very likely that the imperial authorities ordered to remove all the valuables from the sepulchres when they were no longer able to guard the Bight of the Kings properly. Only the sepulchre of Tutankhamen was found in its initial condition.

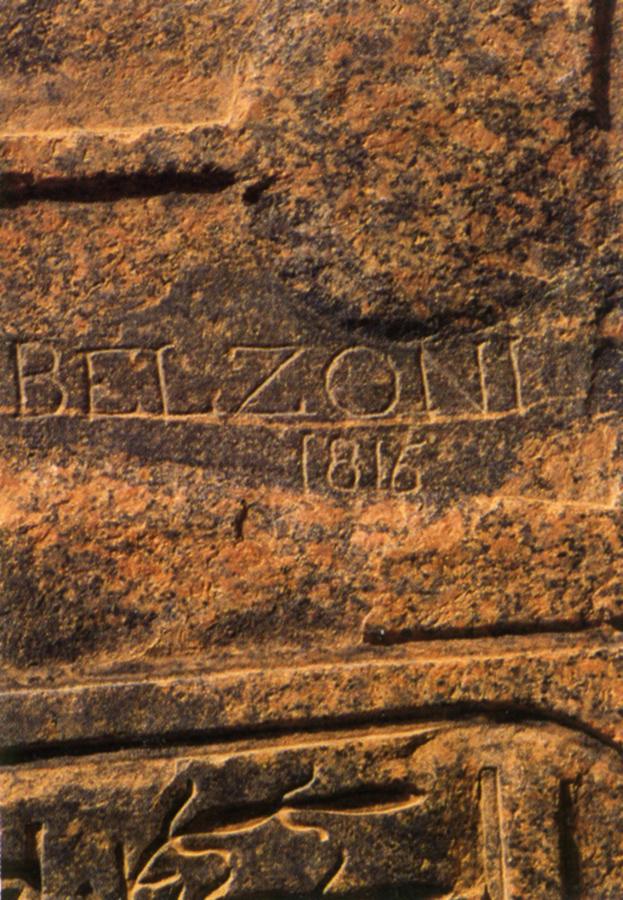

As for the gigantic funereal temples of Karnak and Luxor, they were barbarically destroyed and lay in ruins today. Distinct traces of a raid can be seen in the Karnak Temple to date, for instance (see figs. 16.43, 16.44 and 16.45) – charred ceilings, piles of rubble and so on. The raid must be dating from a relatively recent epoch and not the deepest antiquity, as Egyptologists appear to believe, duped by the erroneous chronology of Scaliger. Otherwise these temples would long be replaced by something else, found more acceptable by the new Pharaohs. However, nothing of the kind has ever been done. It is plainly visible that nobody even tried to reconstruct or rebuild the temples after the raid, at least until they became a tourist attraction, already in our epoch. However, a Muslim mosque and a Christian church were built among the ruins of the Luxor temple – their domes are virtually lost in the gigantic ruins, qv in fig. 16.46. However, both constructions are of a late origin. By the way, unlike the “ancient” Egyptian constructions, they were clearly meant to be used by the locals exclusively, judging by their small size.

Apparently, when the Great Empire was falling apart, and its ruling dynasty was destroyed, the old royal funereal temples got in the way of the new rulers. They were barbarically rendered to ruins, most likely, with the aid of powder and cannons. When the raiders left, the locals started to pull the stones apart in order to use them as construction material. However, there were so many ruins that it has proved impossible to take everything apart. Nowadays the looting has ceased, and the ruins became a tourist attraction. The tourists are told that all these enormous constructions were built several thousand years ago by the mysterious ancient Egyptians, presumably local. In other words, according to the Egyptologists, all the Megalithic construction works were solely based on the local resources of the ancient land situated along the River Nile.

However, a single glance at the “ancient” constructions is enough to realise that the resources and the needs of their builders were drastically different from those of the mediaeval inhabitants of these parts, likewise their modern descendants. Whatever happened to the Egyptians? Our version is as follows. In the days of yore, the Egyptians worked for the enormous Empire spanning Eurasia, Africa and America. Egypt used to be an enormous royal Imperial graveyard, the “land of the gravediggers” that was part of the Great Empire. Therefore, the burials of the kings were the primary occupation of the Egyptians and the main source of income for this land, In other words, the “ancient” Egyptian funereal construction works were based on the resources and the power of the entire Empire, corresponding to its gigantic size and to its needs. When the “Mongolian” Empire fell apart, the local populace ceased to be the “gravedigger nation” and became just like all the other nations, which neither see the funereal rites as their primary occupation, nor as their main source of income.

The representations of the funeral rite as found on the walls of the Karnak temple are considered to refer to the “ancient” Egyptian feast of “Opeth” by the modern Egyptologists. They believe it to be dedicated to the mysterious cult of the “ancient” Egyptian god Amon Ra ([499], page 10). The word “Opeth” as read by the Egyptologists from the hieroglyphic inscriptions upon the Karnak temple, is most likely to be a derivative of the Slavic word “otpevanie”, which stands for the funereal ecclesiastical chants. The root of the word is “pet” (“sing”). This is what the name of the rite derives from.

As for the word “Amon”, the Egyptologists apparently failed to recognize it as the ecclesiastical term “amen”, which stands for “the truth” in Greek and is often used for concluding the Christian prayers. This is why we encounter it so often in ecclesiastical texts; apparently, it is also frequently seen on the walls of the Karnak temple. Let us also note that the craftsmen who made the royal sepulchral caves in the Bight of the Kings were known as “servants in the place of the truth” ([499], page 85). As we have just pointed out, the Greek for “truth” is “amen”.

It is also known that all the craftsmen who worked on the construction of the royal sepulchres in the Bight of the Kings, or Luxor, had also lived right here, in a special village located in one of the valleys and cloistered behind a wall. “The craftsmen that bore relation to the royal sepulchres in one way or another were considered ‘keepers of secrets’, forced to live in a village surrounded by a wall” ([499], page 85). We are fascinated to learn that this “village” was called an “urban monastery” and that it was “populated by the Coptic monks known as the Thebaids” at some point ([499], page 85). However, the Copts were the Egyptian Christians. Therefore, we see that the sepulchres of the “Mongolian” Empire’s Czars weren’t just built by some random craftsmen, but rather the Christian monks of Egypt.

They lived in a monastery, which must have been completely closed for the outsiders. The monastery was located right among the hills of the royal graveyard. The dead monks from this monastery were buried close nearby, in a special necropolis right next to the monastery, in sepulchres consisting of “a chapel and a small painted underground room” ([499], page 85). Such construction of the sepulchres also testifies to the fact that the people buried here were Christian monks. All of this should tell us that the funeral rites of the Czars, or the Pharaohs, were Christian – pertaining to early Christianity, to be precise. Quite naturally, from the point of view of the modern Christian Church, Egyptian burial rites might seem strange and even outlandish. However, one must keep it in mind that the people buried here were members of the royal Imperial house and not just regular folk. Therefore, the rites conducted here may have been substantially different from those performed for ordinary people. Royal funereal rites (known as the Opeth rites) may have been more archaic and possessed some unique characteristics.

It is likely that the memories of this royal Imperial graveyard were preserved in the “ancient” Greek legends about the Phoenix. According to the legend, “the Phoenix is a magic bird . . . named thus by the Assyrians [or the Russians, given that Assyria is Russia reversed – Auth.] . . . The Phoenix looks like an Eagle [cf. the imperial bicephalous eagle on the coat of arms – Auth.] . . . The Phoenix dies inhaling the aromas of the herbs [embalming? – Auth.], but a new bird is born from its seed, which carries the body of its father to Egypt, where the priests of the Sun [or Christ, who is symbolised by the Sun – Auth.] incinerate it” ([532], page 571).

According to other “ancient” Greek legends, the Phoenix isn’t a bird, but rather a human, and a king at that. Moreover, the Greeks believed that Phoenix took part in the Trojan War and was the teacher of Achilles ([532], page 571). This brings the fable-like image of the Phoenix even closer to the Czars of Russia, or the Horde – rulers of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire that they had created. As we can see from the Greek legends, the bodies of the Czars, or the Phoenixes, were indeed brought to Egypt to be buried there.

Thus, it is possible that most of the known Egyptian mummies were brought to Egypt from afar, already embalmed, with the entrails removed and the bodies treated with special chemical solutions. The embalming must have served the specific purpose of preventing the decomposition of the bodies on the long journey from Europe to Egypt across the Mediterranean. One instantly recollects the “ancient” Greek myth about Charon, the carrier of the dead who transported the souls to Hades across some gigantic “river”. This might be a reference to the journeys from Europe to Egypt across the Mediterranean (we have already mentioned the fact that the seas used to be depicted as rivers on the old maps).

There were special priest schools, or church schools, in Egypt, equipped with libraries. This is where the sciences were cultivated.

In CHRON4 we voice the hypothesis that writings found on the walls of the “ancient” Egyptian temples were really the old “Hebraic” (or hieroglyphic) Bible. What we must point out in this respect is that Brugsch, the eminent Egyptologist, points out the proximity between the literary style of the “ancient” Egyptian writings and the Old Testament, which he sees as strange. “We can . . . acquaint ourselves . . . with the images . . . used by the Egyptian poet . . . and the way he expressed his thoughts in the XIV century B. C. and witness that the language of the books of Moses bears some semblance to the images and the expressions used by the Egyptians” ([99], page 474).

7. What were the names of the Egyptian pharaohs?

An unprejudiced reading of the lists of the pharaohs that has reached us as the papyrus of Turin, the list of Manethon and the table of Sakkar puts forth a great multitude of questions if we are to free ourselves from the confines of the Scaligerian chronology. This is what N. A. Morozov points out in [544], Volume 6.

For instance, number 16 in the Table of Abydos is Caesar-Shah, clearly a collation of the word “Caesar” and its Oriental equivalent, “Shah”.

Number 30 is Unas – clearly the Latin word “unus”, the only one.

Number 1 is MNA, pronounced as “menes” by the Graeco-Latin authors. However, this name can be identified as the Greek word “monos”, which means the same as the Latin “unus” – the initial root of the word “monarch” – autocrat, the only king, or rex.

Nearly every name in the “ancient” Egyptian tables contains the word “Ra”, symbolised by the solar circle. Egyptologists believe it to be the title, or the symbol of the theocratic monarch. It must be the Latin word “Re” – “king”, which is still used today; the more recent “ancient” authors transformed it to “reh”, then to “regus”, and eventually to “rex”.

“Re ded” is found under several numbers. However, “ded” is the Hebraic pronunciation of the name David. Under number 14 we see a man with a slingshot, apparently a memory of David killing Goliath with a stone from a slingshot.

The word “beetle” is present in several instances of the table; Egyptologists pronounce is as “Kheper”. This is similar to the Hebraic word “heber”, which translates as “settler”. If we transform this word into “Khepru”, we shall come up with another Biblical word – “hebri”, or “Jew”.

Number 74 is “Re Caesar Kheperu”, which might translate as “Caesar Heber”, or Settler Caesar (King).

Number 13 is Senta – clearly the Latin word “Sanctus” (“saint” or “initiate”).

Number 58 is Sankh-Re, or “Sanctus Rex” (“the Holy King”).

Number 59 is “Re S Khotep Pata-Ab”. “Khotep” means “servant”, “Pata” is “pater” and “Ab” is “father”. The entire name might therefore translate as “Holy King, Servant of the Father of Fathers”.

This easily implies that the individual letters S and Q found in the Abydos table, for instance, simply translate as “sanctus” (“saint”) and “quirinus” (“divine”). This title was borne by Romulus after his deification, for instance ([237], page 847). This also gives us the notion that a separate M stands for “monarch” etc. In other words, all of the above might be abbreviations of standard mediaeval terms.

The name Maren-Re (number 37) might stand for “Marinus Rex”, or “Marine King”. A propos, the Turkish version of this name may have been “Denghiz-Khan”, seeing as how “denghiz” is the Turkish word for “sea”. This resembles the name Genghis-Khan; the Graeco-Roman version would be Ponti-Rex (“Pontus” meaning “sea”). Ponti-Rex easily transforms into “pontifex” – the standard mediaeval manner of addressing the Popes in Italy.

The names and formulae encountered in other “ancient” Egyptian tables such as Biu-Rex (possibly, Pius Rex), Khe-Rex (ho-Rex) and so on further amplify the feeling of strangeness that we get from all the lists of the pharaohs. However, everything will fall into place once we cast aside the Scaligerian chronology, which shifts them thousands of years backwards.

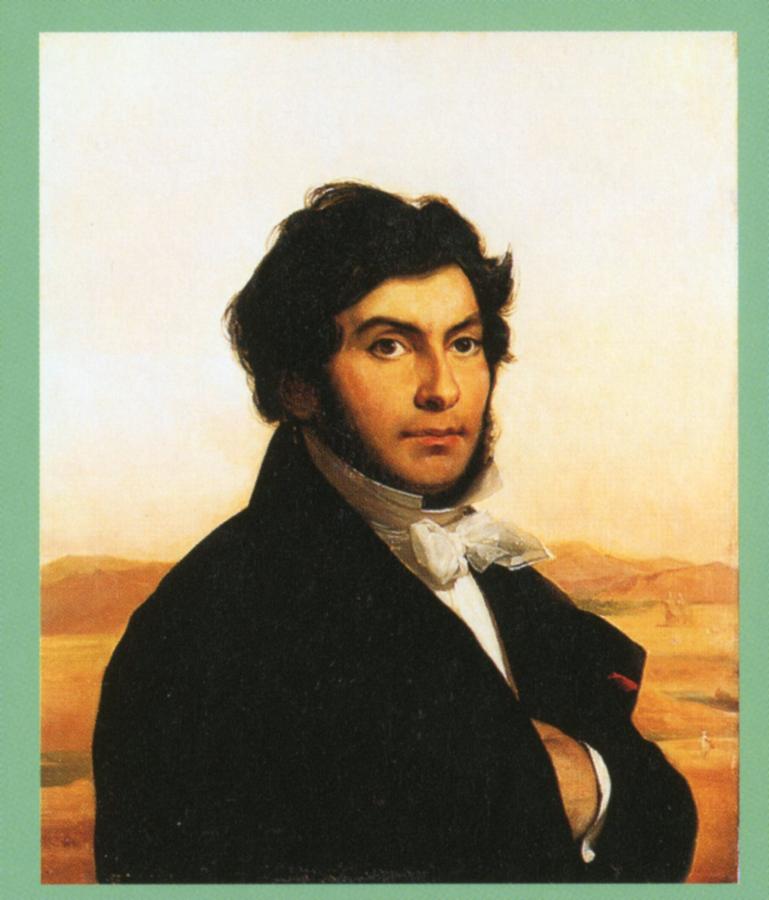

8. Why it is presumed that before Champollion the Egyptian hieroglyphs were interpreted erroneously.

Nowadays we are told that the famous French Egyptologist Champollion, qv in fig. 16.47 was the first one to decipher the mysterious Egyptian hieroglyphs in the early XIX century, revealing the ancient Egyptian texts to the world. One wonders whether the Europeans could have read the hieroglyphic writings before Champollion. It is presumed that they couldn’t – more specifically, it turns out that they could, but allegedly completely erroneously.

K. Keram reports the following: “This might sound a paradox, but the impossibility to decipher the hieroglyphs for such a long time is primarily the fault of . . . Horapolon, who compiled a detailed table of hieroglyphs and their meanings in the IV century A. D. . . . It is quite obvious that this work served as the basis of all the research to follow . . . The lay researchers could set their fantasy free, but the scientists were in despair” ([380], page 94).

Therefore, we suddenly find out that a long time before the great Champollion and up until the XVIII-XIX century certain hieroglyphic inscriptions could still be interpreted. We aren’t speaking about profound understanding, but the general meaning was clear. What made the scientists despair? Could it be that the pre-Champollion interpretation contradicted Scaligerian history? Indeed, historians themselves admit this to have been the reason.

For instance, it turns out that “hieroglyphic inscriptions were ‘interpreted’ as whole passages from the Bible and even as antediluvian literature – Chaldaean, Hebraic and Chinese texts, no less . . . All these attempts to interpret the hieroglyphs were based on Horapolon to some extent” ([380], page 96).

Another example is as follows. One of the French researchers “interpreted the lettering on the wall of the Dendera temple as the hundredth psalm [the Bible once again – Auth.]” ([380], page 95). Egyptian hieroglyphic texts were interpreted as Christian texts referring to Christ ([380], page 95). This is what the research looked like shortly before Champollion.

XIX century historians, who were already raised on Scaligerian chronology, were “absolutely certain” about the “incorrectness” of all such decipherments. Hence the perfectly justified remark of K. Keram about the “despair” of the scientists, who were apparently “left with a single decipherment option – to cast Horapolon aside. Champollion chose this very route” ([380], page 96).

All the translations of the hieroglyphic texts made before Champollion were declared erroneous, and Horapolon was made the scapegoat. However, Keram tells us further: “When Champollion deciphered the hieroglyphs, it became clear that the reasoning of Horapolon was largely correct” ([380], page 94).

One instantly begins to wonder whether Horapolon was actually correct or not. We are told the following. It turns out that Horapolon was correct “in general” – that is to say, he described the hieroglyphic symbols correctly. However, according to Keram, “the very same symbols applied to later inscriptions by the followers of Horapolon put them on the wrong track” ([380], page 94).

Thus, according to the Egyptologists, the dictionary of Horapolon is only acceptable insofar as the “old inscriptions” are concerned, whereas the very same dictionary is categorically forbidden for use with “more recent” inscriptions, since the results of such application scare certain Egyptologists for some reason. For instance, we see the sudden appearance of Biblical texts.

All of this is strange and outright suspicious. If a dictionary is inapplicable to certain texts, the resulting translations should be of a random nature – meaningless sets of words and nothing but. However, we get fragments from the Bible. Apart from that, we see that the “problem of Horapolon’s dictionary” was clearly chronological in nature. Old texts, newer texts . . . What is it supposed to mean, after all?

We are of the opinion that the revealed picture of hieroglyph decipherment in the XIX century is extremely controversial. First Horapolon is accused of “incorrect translations” resulting from this decipherment. Later, after the establishment of Champollion’s authority, it is cautiously acknowledged that Horapolon was largely correct; however, Scaligerites instantly voice objections to the use of his dictionary for the translation of certain Egyptian texts that they consider unacceptable.

After Champollion, it became safe to admit the correctness of Horapolon. All the decipherments excepting the ones made by Champollion and his followers were declared erroneous, since they were “made by laymen”. Champollion’s school is very particular about avoiding the issue of Biblical texts transcribed in “ancient” Egyptian hieroglyphs. No such texts are believed to exist today.

It would be interesting to find out whether Champollion or his followers suggested any validated alternative interpretation of the “ancient” Egyptian texts, earlier presumed Biblical. There isn’t a single word about it in [380].

And so, as we can see, some of the “ancient” Egyptian texts were interpreted as the Bible with the aid of the “ancient” Egyptian dictionary that was compiled in the alleged IV century A. D. This is in good correspondence with our reconstruction as related in CHRON4, wherein we cite the data that confirm the fact that the “ancient” Egyptian texts contain the “Hebraic”, or ecclesiastical, text of the Bible transcribed in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

In CHRON4 we voice the idea that the famous translation of the Bible from “Hebrew” to Greek allegedly performed in Egypt under Philadelphus Ptolemy represents the actual transition from the old hieroglyphic Egyptian transcription to the more recent alphabetical writing. It wasn’t a change of language, but rather the mere way of transcribing texts.

However, in this case there must have been a dictionary with hieroglyphs and their alphabetical Greek equivalents. This is precisely what we see – such a dictionary does appear in the alleged IV century. It is the dictionary of Horapollon.

The Scaligerian dating of Horapollon’s dictionary (the IV century A. D.) means that, according to the new chronology, the dictionary was compiled in the XIV century A. D. the earliest.

Here is another example to demonstrate that the “ancient” Egyptian hieroglyphic texts appear to contain passages from the Christian Book of Psalms. Another thing that needs to be pointed out in this respect is that the texts from the Book of Psalms are frequently encountered in the ancient Russian holy texts, for instance; they are typical for Christian books specifically.

The famous Egyptian Book of the Dead ([1448]) contains a passage that goes as follows, according to the Egyptologists: “He opens the eastern horizon of the sky, he alights in the western horizon of the sky, he removes me so that I may be hale” ([1448], page 108, passage 72).

We are of the opinion that the passage in question is a quotation from Psalm 102 of the Christian Book of Psalms: “As far as the East stands from the West, so he has taken us away from our iniquity” (Psalms 102:12).

One must say that the text of the Book of Psalms is much clearer and easier to comprehend than the translation of the “ancient” Egyptian text suggested by the Egyptologists, although they obviously coincide in general. It is apparent that the Egyptologists do in fact interpret individual hieroglyphs correctly, but don’t always understand the meaning of the text. Indeed, the sequence of hieroglyphic pictograms used for transcribing this passage of Psalm 102 must be as follows: “East”, “West”, “remove” and “strong” (as in “free from sin”, “purified”, “fortified” etc). If the person that reads the hieroglyphs is aware of the meaning of the text in general, the interpretation will be correct.

The translators of the Book of Psalms must have read the original Hebraic (or hieroglyphic, in other words) text correctly when they were translating it to Greek and Church Slavonic. They knew the meaning of the text in question, which had been part of their education. Then their translation became included in the modern version of the Bible, and the hieroglyphs were forgotten. The Egyptologists that try to read the same hieroglyphs today already lack the initial understanding of the general meaning of these texts, which appears to be a sine qua non – it is impossible to read the hieroglyphs otherwise. Therefore, the interpretation of the Egyptologists is obscure and barely comprehensible, although they translate many individual hieroglyphs correctly.

Let us make an observation in re the possible link between the Church Slavonic Book of Psalms, that seems to have preserved the most ancient texts of the Bible, and the Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The Book of Psalms very often repeats the same idea or image twice. For instance, we frequently see sentences consisting of two halves separated by a comma, the second half being a reiteration of the first in other terms. This might result from the fact that the Church Slavonic Book of Psalms was at some point translated from the hieroglyphs directly, and not from Greek or any other language that possesses a phonetic alphabet. It appears that the constant repetitions of a single phrase characteristic for the Book of Psalms are but different descriptions, or translations, of a single Egyptian hieroglyphic pictogram (from the Book of the Dead, most likely). The translation of a pictogram is a description thereof, which may be set in different words; therefore, it would often get duplicated in translation as two slightly different versions – for extra safety, as it were. This explains why the Church Slavonic Book of Psalms hardly contains any Greek words, which would have been plentiful if it had been translated from the Greek. After all, the Russian ecclesiastical terminology contains a large number of Greek words, unlike the Book of Psalms.

The absence of foreign words is perfectly understandable in a translation from a hieroglyphic script – hieroglyphs render the actual meaning of a word and not its phonetics.

9. The question of origins: do the Chinese have Egyptian ancestry, or vice versa?

This question is very interesting indeed, and we aren’t the first to ask it – the history of this issue is rather long. In the XVIII century, “De Guigne declared the Chinese to be the descendants of the Egyptian colonists before the French Academy of Inscriptions [there was such an academy in France – Auth.], supporting his claim by a comparative analysis of hieroglyphs . . . whereas the English scientists were claiming the opposite, namely, that the Egyptians had Chinese ancestry” ([380], pages 94-95).

The issue of close relations between the hieroglyphs found in China, Egypt and the Americas has been discussed a lot, and remains unsolved to this day. Yet the scientists acknowledge the actual existence of such relations.

This concurs with our reconstruction, according to which both African Egypt and the territory of the modern China were colonised by settlers belonging to the same nation during the Great = “Mongolian” Conquest of the XIV century. This centre is recognised as Russia, or the Horde, also known as Scythia and Kitai (China). The latter name was also transferred to the Orient. Therefore, many inhabitants of African Egypt and China in the Far East did in fact come from the same land originally – Scythia, or Kitai (China).