Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 19.

“Ancient” African Egypt as part of the Christian “Mongolian” Empire of the XIV-XVI century - its primary necropolis and chronicle repository.

7. The great forgotten invention of mediaeval alchemy: geopolymeric concrete of the Egyptian pyramids, temples and statues.

As we have mentioned earlier, the learned French chemist Joseph Davidovich proved that not only the Pyramid of Cheops, but also countless stone monuments and other objects, such as sarcophagi, amphoras etc, were really made of a special kind of concrete ([1086], [1087], [1088], [1089], [1090], [1091], [1092] and [1093]). The method of its manufacture became lost eventually, and has only been rediscovered recently by I. Davidovich. At present it is successfully used by European and American manufacturers; I. Davidovich is the patent holder for this technology.

The word "concrete" should by no means confuse the reader. One mustn't think that the "ancient" Egyptian concrete should necessarily resemble its modern counterpart that we customarily see used for construction purposes. Concrete is artificial stone made of ground-up rock treated in a special way - cement, in other words. It can be relatively soft, like limestone. This is the very kind of concrete used in the construction of pyramids - one can easily make it crumble with a pocket knife. It turns out, however, that artificial concrete can be a whole lot harder than the kind that we're accustomed to. As I. Davidovich has discovered, it can be just as hard as granite or diorite, and virtually indistinguishable from said minerals.

Joseph Davidovich is a famous scientist whose speciality is low temperature mineral synthesis. In 1972 he founded CORDI, a private French research company, and in 1979 - the Geopolymer Institute (also in France - see [1092], page 68). He has founded a whole new branch of applied chemistry which was dubbed geopolymerisation - it is concerned with the synthesis of concrete that is almost impossible to tell apart from certain kinds of natural stone. According to Davidovich, "any geological material can be used in ground-up form; the resulting geopolymeric concrete is all but impossible to distinguish from natural stone. Geologists unfamiliar with the capabilities of geopolymerisation . . . mistake geopolymeric concrete for natural stone . . . The manufacture of such artificial stone doesn't require high temperatures or high pressure. Geopolymeric concrete hardens very quickly at room temperature and transforms into pleasant-looking artificial stone" ([1092], page 69).

Davidovich reports that the discovery of geopolymeric stone required nothing but years of observations and experiments. This discovery may well have been made by the mediaeval alchemists. It was for a good reason that one of his books is called "Alchemy and the Pyramids" ([1086] and [1087]). However, Davidovich himself adheres to Scaligerian chronology and prefers to use the term "Stone Age alchemy", allegedly fallen into oblivion thousands of years ago. However, the New Chronology makes the picture more understandable and natural. Geopolymeric concrete as used for the construction of the Egyptian pyramids and statues was indeed discovered by the alchemists - mediaeval ones, that is, as opposed to their mythical predecessors from antediluvian times. We know that alchemy was one of the most important sciences of the late Middle Ages, and studied by many. The construction of pyramids coincides with the heyday of mediaeval alchemy as per the New Chronology.

Later, after the decline of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire and the long wars of the XVII century, many important mediaeval technologies were forgotten. The reason is obvious enough - important technologies of that epoch were usually kept secret. The know-how used for the manufacture of damask, tula and granulation, gold-seeded enamel, geopolymeric concrete and the like was obviously enough classified information and a state secret. After the breakup of the Empire, much information was lost in the atmosphere of chaos and decline; the restoration of these technologies would be a task of the greatest difficulty, since it would require the reconstruction of countless experiments conducted by generations of scientists. Let us remind the reader that the primary scientific method used by the mediaeval alchemists was chaotic accumulation of data void of any system - basically, any ingredients could be mixed together in hope of stumbling across a useful result. Once a valuable discovery was made, it became a professional secret and also a state secret. The most important secrets were only known to a handful of people.

After the decomposition of the "Mongolian" Empire (or, alternatively, after the invasion of a conquering army, as was the case with Egypt in the days of Napoleon, Egyptian craftsmen either got killed or refused to share their trade secrets with the enemy. Many such secrets have been lost as a result. Examples are well-known and plentiful - damask, Rostov enamel, tula and granulation, to name but a few. All these secrets were lost in the XVII century. Attempts are being made to use modern technology for the rediscovery of these secrets, with varying success. In certain cases it becomes perfectly obvious that the Egyptian masters achieved success in a different way - it is impossible to tell exactly how they did it today.

As we are beginning to realise, geopolymeric concrete was one of such lost secrets. Why was it used in Egypt, Africa and Asia Minor primarily? As Davidovich managed to find out, an important component of this concrete was the clay from the River Nile, which contains aluminium oxide ([1092], page 69). Egyptian deserts and salty lakes conceal large deposits of sodium carbonate. The manufacture of geopolymeric concrete requires a number of other components, all of which can be found in Egypt ([1092], page 69).

The discovery of Davidovich gives us the opportunity to solve the numerous mysteries of the "ancient" Egyptian stone objects. It turns out that the mysteries resulted from the failure to understand that in most cases the objects in question were made of artificial stone, or geopolymeric concrete. It was used in the manufacture of statues, the enigmatic "ancient" Egyptian amphoras, and also the building blocks for the Egyptian pyramids. Obviously enough, a special kind of artificial stone was chosen for each purpose - in some cases it was artificial limestone, in others - artificial basalt or diorite.

Let us consider the Egyptian stone amphoras. We are referring to the numerous stone vessels discovered in the "ancient" Egypt. They are made of the hardest kinds of rock - diorite, for example. Some are harder than iron. "Diorite ranks among the hardest rocks. Modern sculptors don't even attempt to use such materials for their art" ([1092], page 8). What do we see in the "ancient' Egypt? Diorite amphoras have a tall and narrow neck, and get wider at the bottom. The thickness of their walls is perfectly uniform (see figs. 19.68a and 19.68b).

Their surface has no marks left by any hard carving tools. Archaeologists are trying to convince us that the amphoras were drilled. But how can one possibly use a drill for making an amphora out of diorite, an exceptionally hard rock, when the neck of the vessel is narrow, its bottom, wide, and the thickness of its walls, uniform, without so much as a single drill mark on the inside? Egyptologists can tell us nothing of how these vessels were made. Instead they are trying to feed us the tale that a craftsman would spend his entire life making a single amphora ([1092], page 119). We believe this to be utter nonsense. However, even if we were to believe that particular piece of disinformation, the issue of how anyone could carve such a vessel out of diorite remains open.The observation of Davidovich leaves nothing of the mystery. The vessels were made of artificial stone on a simple potter's wheel - just like clay vessels. Geopolymeric concrete could be treated in the same way as clay while it was still soft, and so it was used for the manufacture of amphoras, the narrow neck variety in particular. The walls of such vessels were, understandably enough, of a uniform thickness - this is easy enough to achieve on a potter's wheel, if one has the skill in the first place, of course. Upon hardening, such objects transformed into amphoras of hard diorite or quartzite - with no drills attached, as it were.

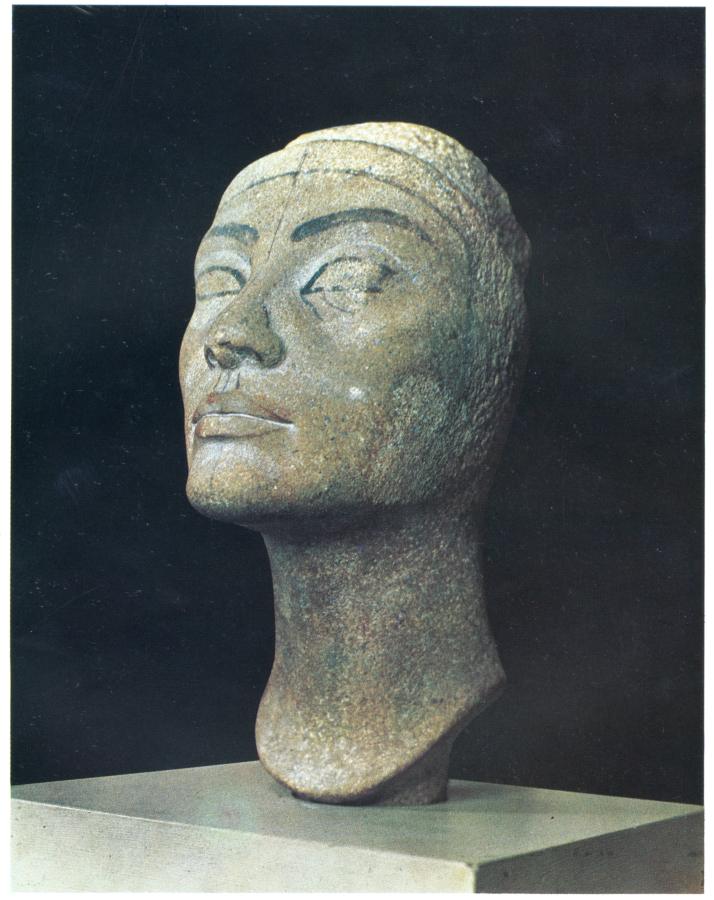

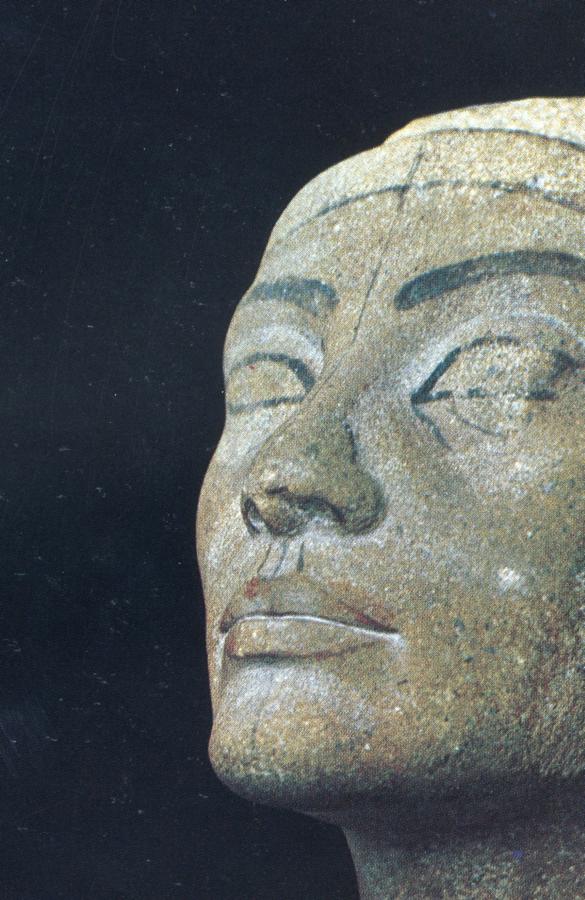

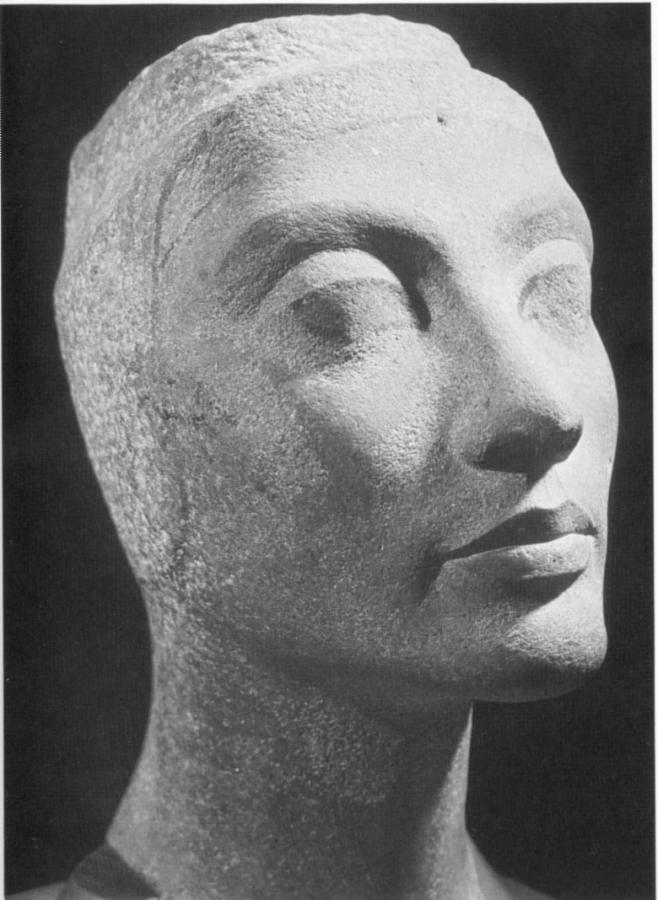

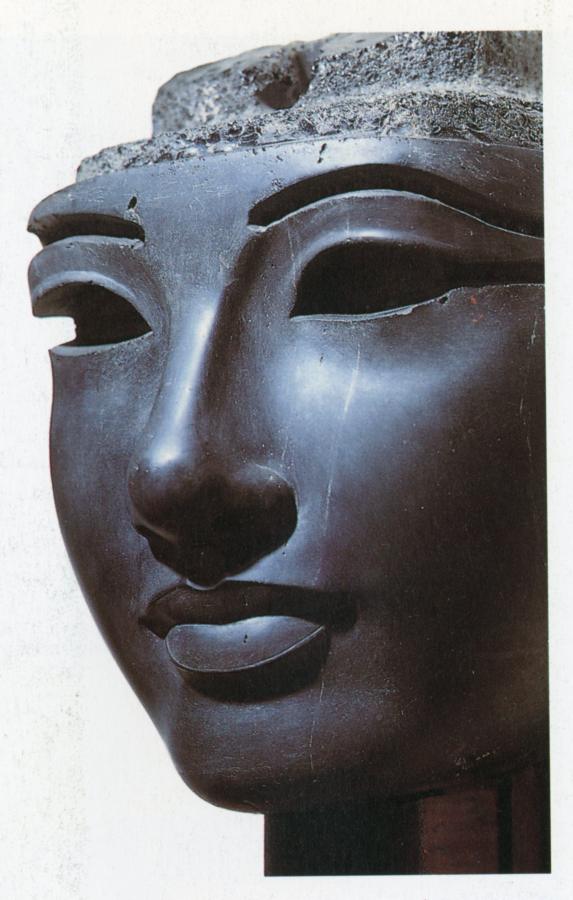

We have discovered actual proof of the fact that artificial stone was used for the manufacture of the "ancient" Egyptian statues - a material that is soft initially and becomes very hard when it dries up, almost indistinguishable from real stone. In fig. 19.69 we see "the unfinished quartzite head of Queen Nefertiti" ([728], ill. 32). It is generally presumed that the sculptor was using natural quartzite. In other words, we are invited to believe that the "ancient" Egyptian sculptor used a copper chisel in order to carve a beautiful sculpture from a piece of hard quartzite, but hasn't managed to finish his work. What do we see? There is a seam that goes right along the symmetry line of Nefertiti's head - across the middle of her forehead, the tip of her nose and the middle of her chin. One sees it perfectly well in the photograph (figs. 19.70 and 19.70a). Such a seam could only have appeared if the sculpture was made inside a ready-made mould. As we know, any mould consists of two detachable halves. The mould would be filled with liquid geopolymeric concrete; when it hardened, the mould was pulled apart. As a result, the sculpture would get seam marks where the parts of the mould are joined. They can be polished away afterwards, which is common practice today. In case of Nefertiti's head the work was left unfinished - the seam is visible perfectly well.

One must say that we've had a spot of luck finding a rare photograph of an unfinished "ancient" Egyptian statue. Finished statues obviously have no seam marks anymore - their entire surface has a high finish (figs. 19.71 and 19.72).

Another curious detail has to be pointed out in this respect. The photographs of this statue that historians choose for the albums on Egyptian art are usually taken from such an angle that this seam on Nefertiti's face remains unseen - for instance, the excellent album [1415] contains a very cleverly made profile of the statue on page 130. No seams anywhere, and no embarrassing questions for the Scaligerite Egyptologists. See also fig. 19.70a.

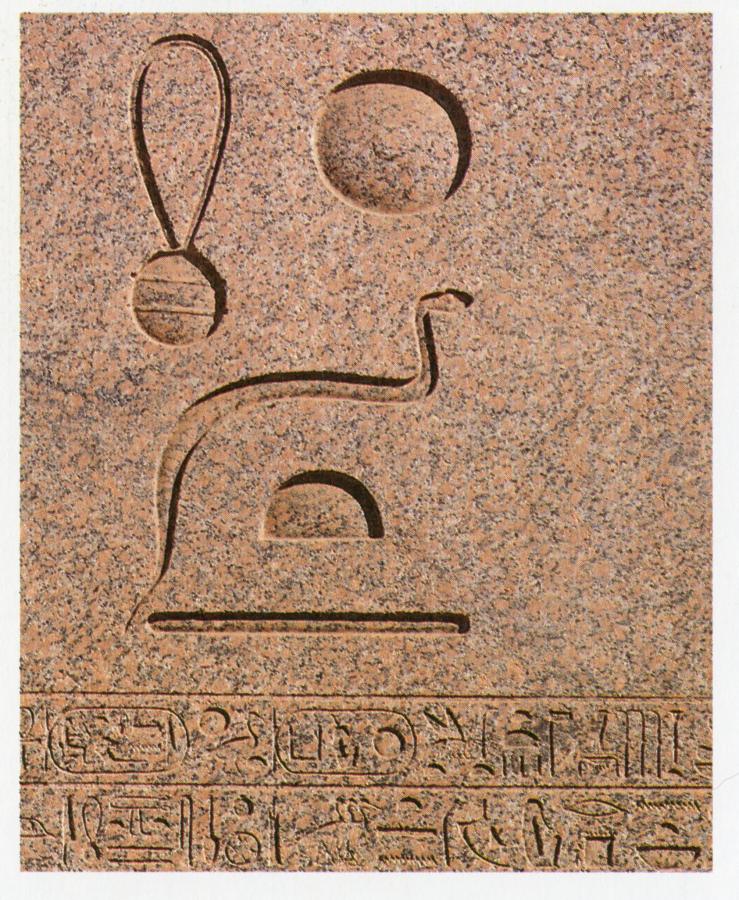

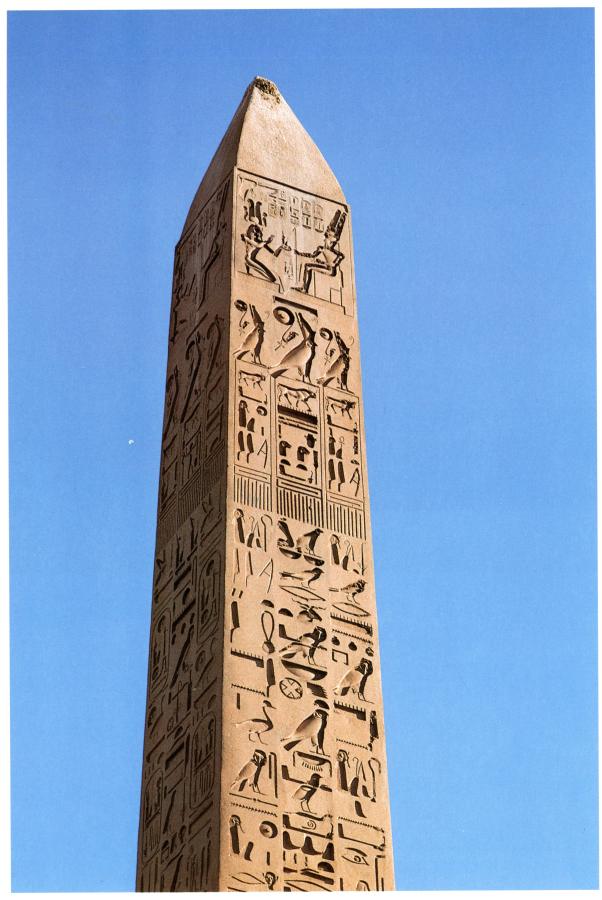

In figs. 19.73 and 19.74 we reproduce examples of the so-called "ancient" Egyptian carvings made in hard granite. This deep "carving" technique has some amazing and truly mysterious properties. According to Davidovich, this "carving technique" becomes even more mysterious underneath a magnifying glass. It turns out that the "chisel" was so steadfast in the hand of the carver that it didn't "jitter" at all. Moreover, upon encountering a hard inclusion, the "chisel" didn't slide sideways, as one may have assumed, but went steadily onwards. The inclusions never have any marks on them. This was a great shock to the first Europeans who came to Egypt with Napoleon. They were forced to admit that all such lettering was made with some mystery method unknown to science ([1092], page 19). Let us also note that the "ancient" Egypt is abundant with such inscriptions carved in hard rock; many of the "carvings" are very deep.

There is nothing to feel mystified about, though. The inscriptions weren't chiselled, but rather impregnated on soft geopolymeric concrete. This is why the extra hard inclusions inside a hieroglyph were simply pressed deeper into the soft concrete without any marks on them. After a while, the concrete would harden and transform into an exceptionally hard rock like granite or diorite, which is very tough even for the state-of-the-art instruments available today.

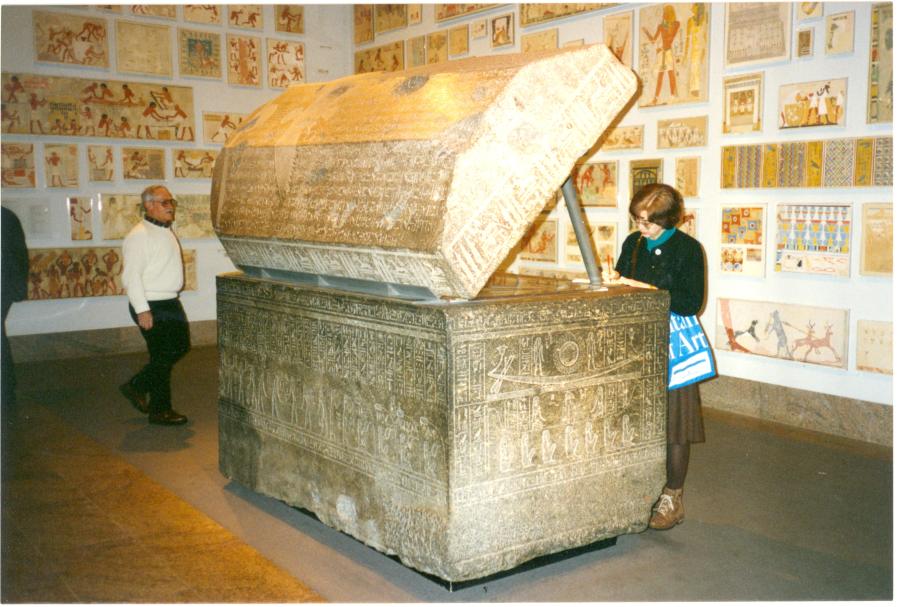

The analysis of I. Davidovich also explains the following mystery of the "ancient" Egyptian constructors. There is a huge sarcophagus inside the Cheops Pyramid, whose very size would not let it pass through the narrower passageways and doors that lead to the chamber where it stands ([1092], page 10; see fig. 19.27 above). Historians invent all sorts of "theories" to explain this, as ingenuous and amusing as such "theories" can only get. For instance, one of them involves the installation of a sarcophagus on a dais and the construction of the pyramid around ([1092], page 43). There are other "ancient Egyptian mysteries" of this sort that still defy explanation. For instance, during the Napoleonic Expedition, the Europeans discovered the famous Valley of Kings with numerous sarcophagi, some of them carved of granite. The Valley of the Kings is a crevice surrounded by tall mountains. The only entrance to this place was carved in the rocks by the Egyptians. No other entries exist ([1092], pages 42-43). Some of the sarcophagi were in pristine condition. According to the report of a certain Cotaz, who had accompanied Napoleon, the gigantic sarcophagus of pink granite whose size has impressed everyone in the party, was as resonant as a bell if one hit it with a hammer, remaining without a single crack anywhere. However, its size was better than that of the entrance to the valley. How such sarcophagi ended up in the valley remains a mystery for the Egyptologists to this date ([1092], pages 42-43). Could they have been dragged over the steep rocks? In that case, why wasn't the entrance to the tomb made a little wider?

Davidovich gives us a simple and to-the-point answer. The Great Sarcophagus was cast on the site out of geopolymeric concrete - nobody had the need to transport it anywhere.

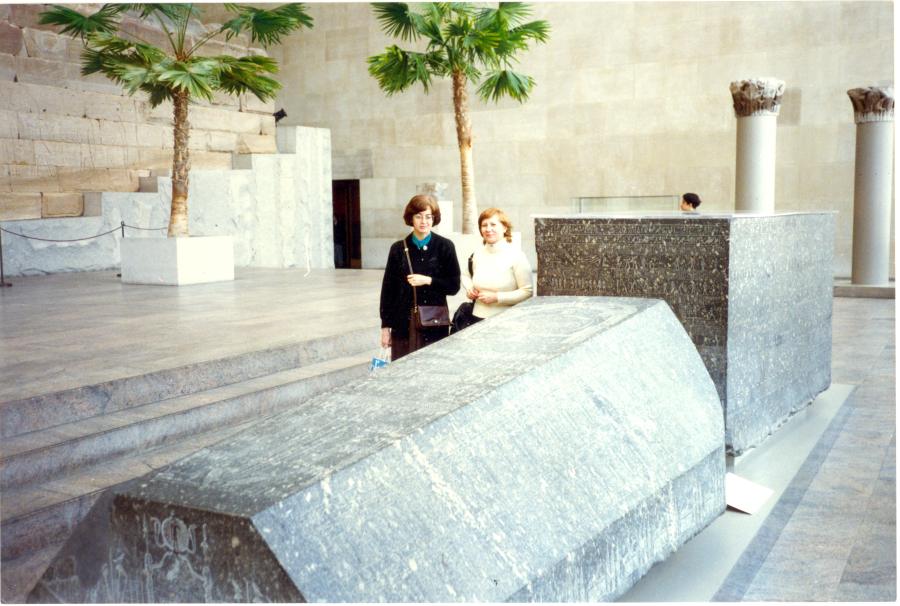

In figs. 19.75 and 19.76 we can see some of the enormous monolithic Egyptian sarcophagi exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of New York.

As a matter of fact, there is no artwork or lettering of any sort anywhere on the large sarcophagus found in the Cheops Pyramid (fig. 19.27). G. V. Nosovskiy and V. V. Sundakov conducted a meticulous study of the sarcophagus in July 2002. Such a total absence of marks is strange, since the rest of the Egyptian sarcophagi designated for burials are covered in all sorts of text and artwork. It might be that the sarcophagus, or the box of Cheops (technically a trunk) had never been occupied by any mummies, but rather contained a part of the imperial treasury saved for a rainy day. Gold, gemstones, valuables and so on. The chamber where the sarcophagi (or trunk) was discovered had been blocked from trespassers by an enormous stone slab. Later on, when the Empire was having a hard time in the XVII century, the sealed-up chamber was opened - a passageway was cut through one of the walls, the sealed chamber was broken into, and the treasure was already taken. The same is true about the Pyramid of Khefren.

Davidovich describes his meeting with the famous French Egyptologist Jean-Philippe Lauer in 1982 ([1092], page 85). Lauer refused to believe that the pyramids were made of artificial stone. He gave two specimens of rock to Davidovich, one of them chipped off the Cheops Pyramid, and the other, from the Pyramid of Teti. Lauer demanded from Davidovich to prove their artificial nature. A chemical analysis conducted in two different laboratories confirmed the specimens to be artificial and not natural rock ([1092], page 85). They turned out to contain chemical elements never found in natural rock. Davidovich made a special report about it at the Congress of Egyptologists in Toronto, Canada (1982). Lauer, who was present at the congress, didn't so much as turn up for the report of Davidovich, although he knew perfectly well that the report concerned the analysis of two of his very own specimens, which he had given to Davidovich. In a newspaper interview Lauer characterised the results of Davidovich in the following terms: "Clever, but impossible" ([1092], page 85).

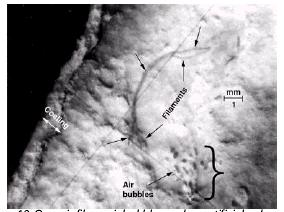

Carrying on with the research of Egyptian pyramid specimens received from Lauer, Davidovich has discovered even more interesting things. For example, he found a hair almost on the surface of the stone (fig. 19.77). Davidovich addressed three laboratories with the request of identifying the object in question. All three were unanimous about the object being "three braided organic filaments, most likely, hairs" ([1092], page 85). The presence of hair in natural limestone is a total impossibility. The formation of limestone took place some 50 million years ago on the bottom of the ocean. No hair (or indeed any other organic matter) is ever found in natural limestone. As for concrete - the hair may have fallen off the head of a worker or a wire rope; nothing uncommon about it.

Davidovich cites a great many more serious arguments that prove the artificial nature of the rock used for the construction of the pyramids and many of the "ancient" Egyptian statues. In an attempt to broaden the scope of his research and find out what the head of the Great Sphinx was made of, he applied to the Egyptian Antiquity Commission in 1984 requesting permission to conduct fieldwork research and obtain specimens of pyramid rock, the Sphinx and the Egyptian quarry rock. His application was rejected under the following pretext: "Your hypothesis is nothing but a personal point of view, and does not correspond to archaeological and geological facts" ([1092], page 89).

Therefore, Egyptologists believe scientific viewpoints to fall into two categories - personal and impersonal. Personal viewpoints can be disregarded, even if they are held by professional scientists. Such a stance virtually turns science into an ideology.

The works of Davidovich give us a new perspective of the goals and the significance of mediaeval alchemy. Scaligerian history is of the opinion that alchemy is "a pre-scientific phase in the history of chemistry. Having originated in Egypt (III-IV century A. D.), alchemy became especially popular in the Western Europe (XI-XIV century A. D.). The primary goal of alchemy was the discovery of the so-called "Philosopher's Stone" . . . The positive influence of alchemy was in the discovery or the refinement of products that had actual practical value (side effects of the search for the miraculous substance) - mineral and vegetable paint, glass, enamel, metal alloys, acids, bases and salts, as well as the development of certain techniques used in laboratories such as distillation, evaporation etc" ([88], page 38). The quest for the Philosopher's Stone was considered a great and noble vocation. Apparently, "Hermes Trismegistos . . . is the mythical founding father of alchemy, who was associated with the following Egyptian gods: Thoth (god of wisdom), Ptah (the patron of arts and crafts) etc . . . Hermes fused together religion, medicine and astronomy, using the three basic substances for his 'great quest' for the Philosopher's Stone" ([245], page 26, comment 10).

Therefore, the primary objective of alchemy, which had originated in Egypt, where geopolymeric concrete was used the widest, was the synthesis of the Philosopher's Stone - "the stone of science", in other words, since the word "philosophy" stood for science in general in the Middle Ages. Nowadays historians believe that the Philosopher's Stone of the mediaeval alchemists was some mysterious stone that could transform iron to gold, suggesting to us that the mediaeval alchemists were chasing phantoms in general, discovering useful things only by chance, without really meaning to. "In the West the belief in the Philosopher's Stone inspired people to conduct research that was shrouded in mysticism and described allegorically . . . Some were so certain about the magical properties of the Philosopher's Stone that they compiled whole handwritten volumes, which strike us as naîve today" ([245], page 45).

However, in the light of the works of Joseph Davidovich we are beginning to realise that the "scientists' stone", or the "Philosopher's Stone" was the very artificial stone of the Egyptian pyramids and statues, or geopolymeric concrete. Apparently, a great many "mysterious" stone monoliths of mind-boggling size, such as the English Stonehenge, the Lebanese Baalbeq etc, were made of the Philosopher's Stone in the epoch of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire. The secrets of artificial stone manufacture were kept secret from the locals by the imperial scientists who had come from afar. When the Empire fell apart, the West Europeans obviously felt very eager about discovering the secret of the mysterious Philosopher's Stone. Local Western European alchemists of the XVII-XVIII century must have been extremely laborious in their attempts to solve the mystery, but to no avail. This must be how the legend of the endless and fruitless endeavours of the mediaeval alchemists searching for the Philosopher's Stone came into being. The experiments were eventually abandoned, and the term "Philosopher's Stone" took on a fantasy hue, coming to mean a miraculous stone that could transform iron and other metals into gold.

Incidentally, the history of alchemy claims that the Egyptians had already known the secret of the Philosopher's Stone, but lost it at some point ([1461], Volume 2, page 216). There is a mediaeval story about a certain Egyptian named Adfar, a native of Alexandria, who found the book of Hermes with the instructions how to make the Philosopher's Stone. Adfar passed this knowledge on to Morienus, a young Roman (fig. 19.78). A while later, the Egyptian King Kalid ordered his alchemists to make him the Philosopher's Stone. They failed to comply; however, Morienus came to Kalid and made the stone. The king ordered for the other alchemists to be decapitated. However, Morienus disappeared without revealing the secret. After a while one of the king's servants managed to find Morienus and started to pester him with questions about the manufacture of the stone. Morienus answered the questions. Apparently, the Philosopher's Stone consisted of four compounds. Morienus said that in order to get a stone one needed to break a stone first ([1461], Volume 2, page 217). It is possible that the legend has preserved a memory of the fact that the artificial geopolymeric stone was made of destroyed (ground-up) rock.

The necessity to use several compounds (apparently, four of them altogether) is also in perfect correspondence with the actual manufacture of artificial geopolymeric stone, which is a product of a chemical reaction of several components ([1092], pages 69-70). Morienus used allegorical names for referring to the compounds of the Philosopher's Stone, such as "white smoke", "green lion" etc ([1461]). Later on the alchemists attempted to interpret these symbolic names, but without any success, since they haven't managed to come up with the Philosopher's Stone.

Nowadays, after the discovery of Davidovich, the mystery of the Philosopher's Stone, the Egyptian pyramids, the English Stonehenge and other similar constructions made of stone ceases to exist. This understanding could only have dawned upon us after the rediscovery of geopolymeric concrete, which must have been a professional secret of the alchemists of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire.

Let us note that specialists believe the very word "chemistry" to be a derivative of the Egyptian word "Kham" or "Khemi", which had stood for "Egypt" ([245], page 11). We see that the name of the scientific discipline is associated with the country where the artificial stone was used in construction the most extensively. "Alchemy" must have stood for "Great Chemistry", and possibly an even older translation would be "Great Kham" (Khan). It is thus possible that chemistry was considered an imperial science, or the science of the Great Khan.

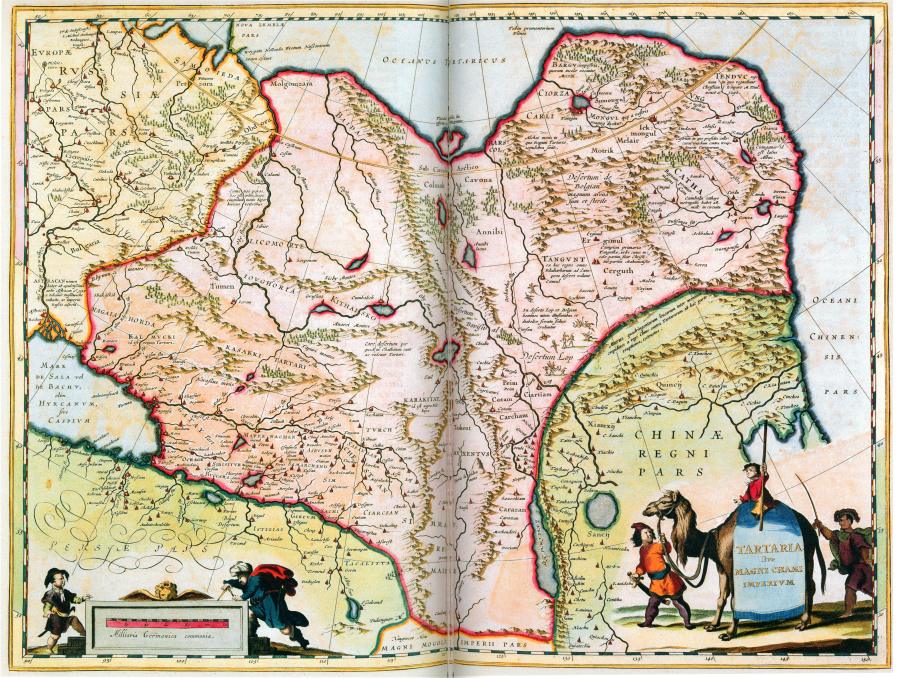

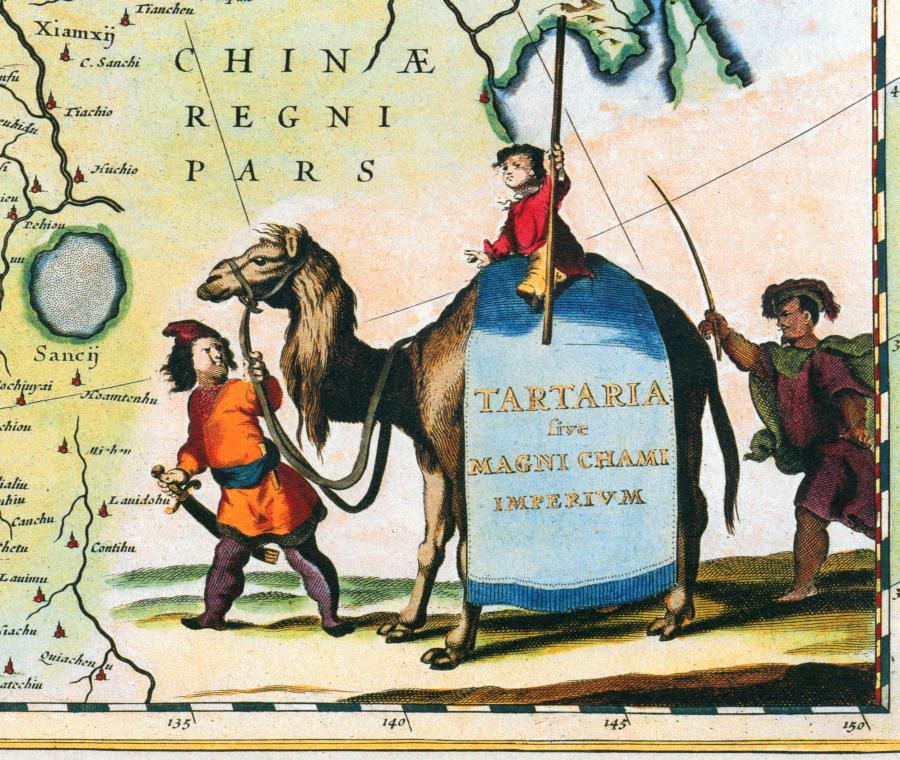

In fig. 19.79 we have reproduced an ancient map called Tartaria Sive Magni Chami Imperium. A close-in of the map can be seen in fig. 19.80. What we read clearly translates as "Tartary, or the Great Kham's Empire". It is perfectly obvious that we see an antiquated spelling of the Khan's title here - he can be identified as the Biblical Ham, one of Patriarch Noah's sons (Genesis 9:18). Furthermore, according to the Bible, "Ham was the father of Canaan" (Genesis 9:18). Thus, the names Kham, Khan and Canaan were in close relation and must have had similar translations.

Thus, the Great = "Mongolian" Empire was also known as the Empire of the Great Kham (or Khan). We have seen a vestige of this name in the old name of Egypt - Kingdom of Kham. Let us remind the reader that according to our reconstruction the Biblical Egypt can be identified as Russia, or the Horde, of the XIV-XVI century.

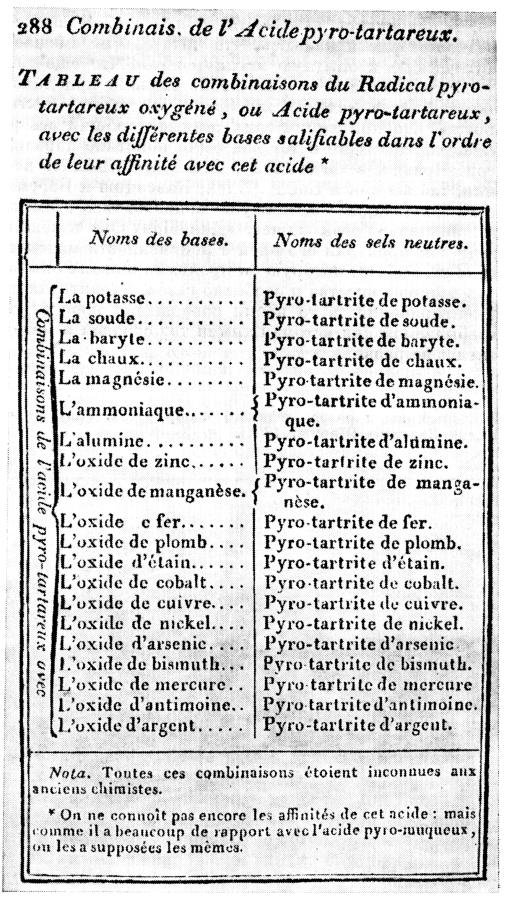

One has to note that mediaeval alchemy widely employed the word "Tartar" (or "Tartarus") - Great Tartary. For instance, neutral potassium tartrate was known as "Tartarus Tartarisatus", iron tartrate was "Tartarus Chalybeatus" and so on ([245], pages 65-66). The latter may be related to the word "Caliph". Also, "potassium tartrate . . . was known as 'Tartarus' since the time of the alchemists . . . which is when it was also used for referring to different salts - this usage has outlived the alchemists" ([245], page 80, Comment 5). In fig. 19.81 we see a page from the book of Lavoisier dating from 1801 with a table of acetylformic acid compounds ([245], page 143). We see the term "Pyro-tartrite". There was a whole scientific discipline of "Tartarology", and there were publications under that title ([245], page 65). Tartar science, perhaps?

The picture is perfectly clear. Chemical research was an important issue for the state, and so the "Mongolian" Empire was financing it in the epoch of the XIV-XVI century, hence the connection with the name "Tartar". It was much later that word "Tartar" took on a negative connotation in the Reformist Europe - it became threatening: "Tartarus . . . is the underworld, or inferno in the ancient Greek mythology; Homer describes it as the abyss where the Titans and Kronos were thrown by Zeus" ([245], page 79, Comment 4). In general, everybody needed to know what a horrendous place Tartary was.