Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 20.

Pharaoh Thutmos III the Conqueror as the Ottoman = Ataman Mehmet II, a conqueror from the XV century.

5. The Ataman conquest of the Mediterranean region, Asia Minor and Europe in the XV century, according to the “ancient” Egyptian texts.

5.1. The conquest of Kadesh by Thutmos III.

The wars of Thutmos III were described in the detailed “ancient” Egyptian chronicle in stone cited by Brugsch in [99], pages 303-325. Before we proceed to analyse this source, let us note it right away that the lettering in question suffered greatly from the chisels of later researchers – many names of people, cities and nations have been destroyed completely, especially in such interesting places as the description of the actual storm of Kadesh etc [99], page 307).

The lengthy list of 119 cities conquered by Thutmos III and the cities of his allies begins with the city of Kadesh on the Orontes (99], page 329). As we already know from the biography of Ramses II, it is most likely to identify as Czar-Grad, the largest and most important city conquered by Thutmos III, hence its placement at the top of the list.

The second city in the list of Thutmos III is Maketa, or Megiddo. The name is obviously a reference to Macedonia.

The chronicle calls the king of Kadesh on the Orontes enemy of Thutmos III ([99], page 304). The king of Kadesh is the ally of the king of Maketa = Megiddo, or Macedonia – they both fight against Thutmos III.

This is what we learn from the lettering: “Then they (the enemies) ran to Megiddo, with terror on their faces, and left their horses and their chariots of silver and gold, and were taken up the walls of this city by their garments as if they were ropes, for the city was locked in fear of King . . . [followed by a chiselled-off part] . . .

As they were pulled up the city walls in their garment, o, had the King’s warriors resisted the urge to capture the possessions of their enemies . . . [another chiselled-off part] . . . Megiddo that very hour. For the abject king of Megiddo and the abject king of this town (Megiddo) were raised in such a way that they managed to escape and enter their city.

And the Pharaoh was furious [a large passage has been chiselled off here] . . . . . . . . .

And so his royal might brought him victory. Then his enemies’ horses were taken . . . Tied up, they were throbbing like fish on dry land . . . And so the camp of the despised king was taken, likewise his son. And the warriors cried out in joy, and gave praises to Ammon, Lord of the Thebes, who gave victory to his son . . . [chiselled-off piece] . . . And they laid out their exploits before the king: severed hands, live captives, mares and chariots . . . The power of Megiddo equals (or represents) the power of a thousand cities, which you must take . . . [another chiselled-off passage] . . . the leaders of the guard . . . And the king wished to stay there, in the east of the city, as though he were in a stronghold.

(The king) ordered to build fortifications around the place – thick walls with spikes” ([99], page 307).

It is possible that the capture of Kadesh was joined with the conquest of Macedonia (Maketa) = Megiddo here. “Certain details pertaining to the storm of Kadesh are found in the account of Amenemkhib” ([99]), page 340).

What is the tale about? Apparently, the conquest of Byzantium, the Balkans and Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453. The “ancient” Thutmos III the Conqueror identifies as the mediaeval Mehmet II the Conqueror, as we understand today.

The very same events became reflected in the “ancient” Greek history as the foundation of the Macedonian Empire by the “ancient” Philip II the Conqueror. His son, Alexander the Great, brought the Empire to the very summit of its glory (see the description of the parallelism in CHRON2, Chapter 3:18. According to our reconstruction, the “ancient” Thutmos III, the mediaeval Mehmet II and the “ancient” Philip II are but different names of one and the same historical personality of the XV century.

5.2. The location of the largest obelisk built to honour Thutmos III = Mehmet II.

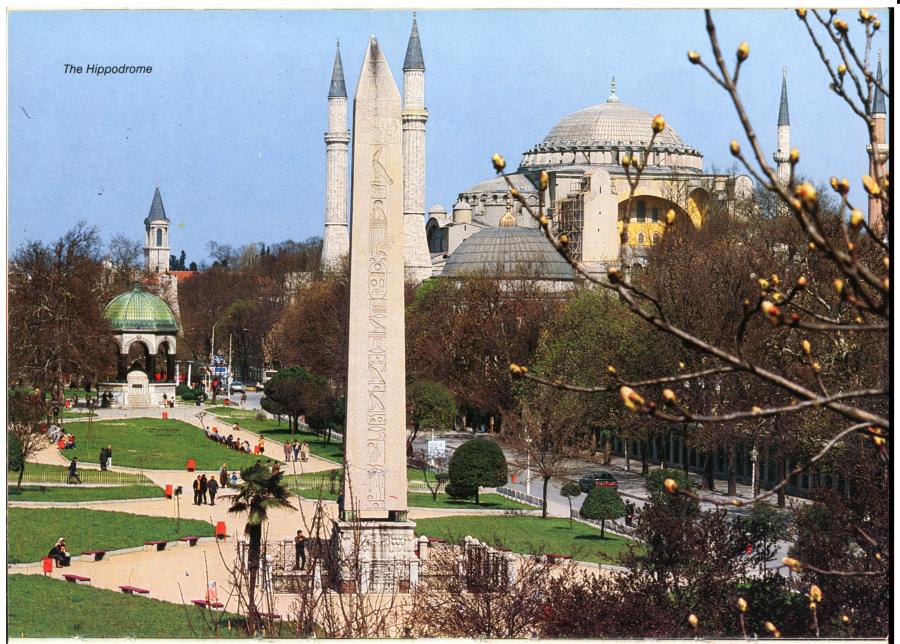

It is in Constantinople – not African Egypt, but rather the Ottoman = Ataman Empire (see fig. 20.3).

Brugsch reports: “The largest of the obelisks built to commemorate Thutmos III that we know of is the Constantinople obelisk. Excellently carved hieroglyphs cover all four sides of this enormous monolith of pink granite . . . At the centre of this . . . inscription we see the phrase that has actual historical value: ‘King Thutmos III walked all across the Land of Nakharina, as the victorious leader of his army. He has stretched his borders to the edge of the world and the sea at the back of Nakharina’”([99], page 376).

Here the “Land of Nakharina” must stand for “nagornaya zemlya” – “the hilly land”, or Greece (whose name can also be interpreted in the same manner, qv in [544]). It is a Slavic name formerly used for referring to Byzantium. In other languages Byzantium was called differently – Romea, for example.

Most probably, this “ancient” Egyptian obelisk was built by Mehmet II = Thutmos III after the capture of Czar-Grad = Troy in 1453. Incidentally, one of the implications is that regular people who passed by the obelisk could still understand hieroglyphic writing in the XV century.

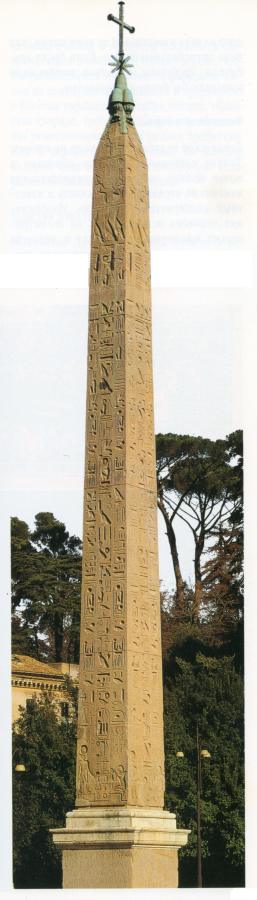

5.3. Another obelisk of Thutmos III = Mehmet II in Italy.

However, it wasn’t just Byzantium that Thutmos III = Mehmet II conquered. Another obelisk of his can be seen in Italian Rome. Brugsch reports: “One of the obelisks . . . was taken to Rome by the Romans and installed on the square known as Lateran today. The name of Thutmos III was read upon it; inscriptions mention him in the following context:

‘The king ordered to build this great obelisk in front of the main entrance to the temple in the region of Apa as the first of many royal obelisks at Ous to be built’ . . . Elsewhere we read the following words: ‘The king has ordered to build this great obelisk at the top entrance to the Temple of Apa, facing the City of Ous’” ([99], pages 376-377).

We have removed the explanatory notes of Brugsch that he places in parentheses. Brugsch tries to locate the places referred to in the lettering on Egyptian territory. One must admit that he isn’t very successful here – instead of Apa he proposes “Karnak”, apparently finding no better option, and instead of Us, “Thebes” – also having found nothing better? But Brugsch has nowhere to retreat, since the Egyptologists are certain that the obelisk was brought to Italy from Egypt, and may therefore mention nothing but Egyptian geography.

Yet the obelisk stands in Italy, and was erected here by Mehmet II, as we understand – or Thutmos III. He had no need to order for an old Egyptian obelisk to be brought here – he could easily install a new obelisk in Italy, which he conquered for the second time, as we understand now. There was plenty of inexpensive work force there. He was also familiar with the hieroglyphs, likewise most people around him. We have already cited photographs of the Italian obelisk in CHRON1, Chapter 7:6.3.

Let us now take a closer look at the names mentioned in the lettering on the obelisk of Thutmos. We instantly notice the famous Italian name Apa – Apulia. This is the name of the Italian peninsula’s “heel”. The entire peninsula is also known as the Apennines – we see the same root used ([797], pages 67 and 70).

The city of Ous as mentioned on the Obelisk of Thutmos also strongly resembles the name Rous (or Lous).

Let us now regard the map of Apulia. We shall instantly see the large city of Lecce; the coastal part of the Apulian peninsula is also called Leuca (more precisely, ‘Cape of St. Mary of Leuca’. Given the constant flexion of R and L and vice versa, we can also read the names as “Rus”.

However, we do not insist on this interpretation of the name “Ous” as mentioned by Thutmos. Given what we already know about the Etruscans, it makes no sense to meditate on the meaning of the mysterious “Ous” in the lettering of Thutmos. It meant “Rus” – possibly, the same root as in the word “Etruscan”, or a reference to either Lecce or Leuca.

The largest city of Apulia is Taranto – “tyrant” or “pharaoh”, in other words! This must be where the Obelisk of Thutmos was installed initially – in the city proudly bearing the name of the Pharaoh, or Taranto. It wasn’t until much later, when the Italian Rome founded at the end of the XIV century as the “Mongolian” affiliation of the Imperial Catholic Church was transformed into the centre of the “new Catholic Church” in the XVII century, that the obelisk from Taranto, the City of the Pharaoh, was taken to Rome, after many a tribulation. This must have happened already in the XVII century of the New Era – the “ancient” Rome was busy hoarding antiquities aimed at proving its “great age”.

This must be when the obelisk “was taken to Rome and installed on the Lateran square” ([99], pages 376-377). The name is possibly derived from “la Taranto”, which will once again make it mean “Pharaoh Square”.

In fig. 20.4 we see yet another “ancient” Egyptian obelisk in Rome, which is believed to have been brought here from Egypt. We see it topped by a Christian cross; historians are trying to convince us that the cross was “a more recent addition”; we may as well doubt it – most likely, the cross was there from the very start, since the obelisk was erected by the Christian pharaohs of the “ancient” Christian Egypt in the XIV century A. D. the earliest.

5.4. The union of the Ruthen tribes.

The “ancient” Egyptian inscriptions, which, as we understand today, describe the epoch of the XV century A. D., tell us a great deal about Russia, or the Horde. Let us remind the reader that the “ancient” Pharaoh Thutmos is most likely to identify as the mediaeval Mehmet II. Failing to realise the true meaning of the texts in question, Brugsch writes the following, using virtually the same words as Orbini:

“In Canaan [the Land of the Khans – Auth.] there was a great union of tribes of a common origin, known under the general name of Ruthens. These nations were governed by a host of local kings occupying fortified cities . . . A special role was played by the King of Kadesh in Orontes, ‘the land of Amorrheans’, according to the inscriptions” ([99]), page 334) – this is what we learn from Brugsch, who writes it without realising the true meaning of his own words.

However, all of the above makes everything perfectly clear. The “ancient” Land of Canaan is the land of the Khans of the XIV-XVI century.

The “great ancient union of tribes” is the Russian (“Mongolian”) Empire that was formed in the XIV century. Its name “Ruthen” is also of an obvious enough origin – the word “Orda” (“Horde”). The Great Empire was indeed divided into local principalities (known as “ulus”) governed by local princes. Among them – the Western Europe, the Balkans, China, India, Iran, Japan, Africa, parts of America etc (see CHRON6). The vicegerents of the Horde are patronisingly referred to as “a host of local kings” in Brugsch’s work, since he failed to realise that the Scaligerite historians of the XVII century artificially compressed the Great Empire, or the Land of the Khans, to the tiny spot of scorched land in the modern Palestine.

The “Kadesh on Orontes in the land of the Amorrheans” identifies as Czar-Grad in the land of the Romeans on the straits (or the river) of Bosporus. Obviously enough, the ruler of Czar-Grad enjoyed a special status, if only for the reason that Constantinople (a. k. a. Jerusalem, or New Rome) had been the Holy City of Jesus Christ.

Brugsch continues: “This union of the Ruthen tribes was joined by the Phoenician Khalu, who had lived near the sea and were called Tsakhi by the Egyptians” ([99], page 334). Here we see a list of nations that inhabited the Northern (or European) coast of the Mediterranean – the Khalu = the Gauls (France), then the Phoenicians (or Venetians), and, finally, the Tsakhi (the Czechs = the Austrians).

Brugsch goes on and on, still failing to realise anything: “Their main city [“they” = the union of the Ruthens – Auth.] was Aradus” ([99], page 334). This is simply a reference to the fact that Russia was led by the Horde, or Aradus. Then, having conquered many a nation in the XIV century, the Horde has left its mark there – in particular, as the Russian names of the cities, geographical regions, rivers, mountains and lakes. This must be how the city of Arad appeared in Romania, likewise the city of Oradea. They are right next to the Hungarian border, qv in the modern map.

Furthermore, “the same union [the union of the Ruthen nations, or Russia – Auth.] was joined by the Kiti, also known as Khittim (or Khettei) of the Holy Writ [! – Auth.]” ([99], page 334).

Let us remind the reader that nearly every single name cited by Brugsch is already known to us quite well. The two last names – Kytia, or China (Scythia), alias Russia (see Part 6) and “Hittites” (Goths, or Cossacks) are so blatant (given the sum total of our knowledge at this point) that we can be positive enough when we claim that the union of the Ruthen tribes as described in the “ancient” Egyptian chronicles is Russia, or the Horde, in the XIV-XVI century.

We must also point out that Russia, or the Horde, already included the entire Western Europe in the epoch described above, France being no exception (see above).

5.5. The new Ataman conquest of Europe in the XV century by Pharaoh Thutmos = Mohammed.

Let us carry on with reading the Egyptian chronicles – a most fascinating pastime, once we realise what they are really telling us about.

We are about to proceed with reading about the history of the Ottoman = Ataman conquest of Europe in the XV century, which is known to us well enough from mediaeval history. It can be considered a “new conquest”, after the Great = “Mongolian” conquest of the world in the XIV century as described above. Let us now add a few important details thereto. As we have discovered, a meticulous account of this conquest is also provided by the monuments of the “ancient” Egypt. Let us linger on our reconstruction of the conquest for a longer while.

In the XIV century, or about 100 years before the events in question, Russia, or the Horde, already conquered a large part of the Western Europe, Asia and Africa, founding the Great = “Mongolian” Empire as a result.

However, the monolithic nature of the empire would eventually collapse due to reasons laid out in CHRON6. Towards the beginning of the XV century the imperial vicegerents founded more or less independent countries all across the empire, and those were striving for independence. A power struggle began between the descendants of Georgiy = Genghis-Khan and Ivan Kalita = Batu-Khan. This is why the Russian chronicles describe the first half of the XV century as a time of strife.

The Ottoman = Ataman Conquest of the XV century was, in particular, aimed at strengthening the unity of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire. This was implemented successfully. As we mentioned above, the time in question, or the period of roughly 30 years that followed the conquest of Czar-Grad, was when the authority of the Ataman Czar-Grad, or Judea, was even recognized by the capital of the Great Empire, or the Horde itself.

Therefore, the Ataman conquest of the XV century was de facto a reaction to the internecine power struggle within some of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire’s provinces.

This is what Brugsch writes about the campaigns of Thutmos: “The main battlefield was the triangular area between Kadesh, Semira and Arad” ([99], page 334). It is perfectly easy to locate said triangle on the modern map of Europe.

1) The city of Constantinople, referred to as “Kadesh” by the “ancient” Egyptian lettering.

2) The city of Smyrna, or the modern Izmir in Turkey, to the south of Constantinople. The “ancient” Egyptian lettering calls it “Semira”. It has to be remarked that Smyrna is the “ancient” Greek name of Izmir ([797]), which was naturally used in the “ancient” Egyptian lettering.

3) The city of Arad in modern Romania, to the northwest of Constantinople. The “ancient” lettering calls it Arad, or the Horde.

Let us linger on the “ancient” Egyptian name of the “Land of Rivers”, or Nakharain ([99], page 342). Egyptologists believe it to be the old name of Mesopotamia ([99], page 342). We have suggested several other (European) versions of its identification.

First version. Initially (in the old chronicles) this name stood for the Nogai Land or the Nogai River (Volga?) = Nogai-Rhone.

Second version. Nakharain = “nagornaya strana”, or the “hilly land” (Greece).

Third version. In later chronicles, dating from the epoch when the “Mongolian” Empire spread wider and swallowed the entire Western Europe, “Nakharain” may have been voiced as the German “nach Rhein” – “towards Rhine”, the famous German river.

Germany also inherited the moniker “Assyria”, or “Asher”, imported from Russia, or the Horde, as well as “Prussia”, while its inhabitants started to refer to themselves as to “Goths”.

5.6. A list of the numerous conquests of Pharaoh Thutmos = Sultan (Ataman) Mehmet.

Brugsch reports the following: “A closer study of the remaining victory records in the list, which describe every campaign of the king starting with the Battle of Megiddo [in Macedonia – Auth.], reveals that Thutmos III launched a total of 14 campaigns between the 23rd and 40th year of his reign . . . Insofar as the chisel marks permit [sic! – Auth.], we are referring to the data contained in this list” ([99], page 340).

It is known that, having captured Constantinople and the Balkans in the XV century, the Ottomans launched their main strike at the Western Europe – in particular, the Latin countries, including Italy and Austria, which also figure in the “ancient” Egyptian chronicles as “Luthenia”. The main territory of the “Luthenia” (or Ruthenia) identifies as Russia, or the Horde.

Brugsch wrote: “The name of the Ruthennu (or Luthennu) nation was mentioned often and played an important part in the history of the 18th dynasty” ([99], page 243).

Thus, after the XIV century the Latin Western Europe became known as Latinia, or Luthenia – a province of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire. One of its centres was in Austria, Vienna being the capital. The name Vienna is likely to be a derivative of the Russian word “venets”, “crown”, or the name of the Slavic tribe – the Venedes, qv in Orbini’s book and in Chapter 9 of CHRON5.

Moreover, the very word Austria (as Austrriki) is one of the old names borne by Russia (the Horde), also known as Scythia – see more in the Scandinavian geographical tractates in Part 6 of the present book. It is little wonder, then, that the European Austria, assaulted by the Atamans, was called “Ruthena” or “Luthena” – Latinia, that is, in the “ancient” Egyptian chronicles, as we shall see below.

Therefore, the name “Ruthena” as used in the “ancient” Egyptian chronicles stood for the actual Horde, or Russia, and also Latinia (the Western Europe) in the more recent chronicles. This is why Brugsch refers to two Ruthens, apparently failing to understand the matter at hand:

“Upper Ruthen was the hilly Palestine, which included Lebanon, whence the travellers came to Lower Ruthen, or Syria” ([99], page 328).

Since Lebanon is most likely to identify as the European Albania, and Palestine is the Italian Palestrina, “Upper Ruthen” must be the name of Latinia, or the entire Western Europe. The word “upper” shall translate as “western” in this case. Let us remind the reader that the ancient maps were often inverted in relation to their modern counterparts, qv in CHRON1. The Syrian Ruthen identifies as Russia, or the Horde, the heart of the Empire, as we already mentioned above. The word “lower” shall be referring to the East in this case.

Brugsch sums up as follows: “The primary targets of Thutmos over the course of several years were the follows: Ruthen [Luthen – Auth.] and Tsakhi [the Czechs – Auth.]” ([99], page 303). The countries in question are the West European Latinia and the land of the Czechs.

“After the victories of the Pharaoh, both countries had to recognize the victor as their suzerain” ([99], page 303). Everything is perfectly correct – Italy, the Czechs and several other nations of the Western Europe start paying tribute to the Ottomans = Atamans, as well as to the Horde (see CHRON5, Chapter 12:3.4).

Brugsch cites the following list of the campaigns of Thutmos, which he took from the “remnants” of the “ancient” Egyptian lettering.

“In the year 23 we have the first campaign against the Ruthens [or Latinia = the Western Europe – Auth.].

In 24-28: the second, third and fourth campaigns against the Ruthens [or Latinia = the Western Europe – Auth.].

In 29: the fifth campaign. The assaulted cities are Tunep [apparently, a derivative of “Danube” – Auth.] and Arad [possibly, the city of Arad in Romania – Auth.]. The land of Tsakhi is laid desolate [most likely, the land of the Czechs and not Phoenicia (or Venice), as Brugsch appears to think – Auth.]

In 30: the sixth campaign against the Ruthens [or Latinia = the Western Europe – Auth.]. The cities of Kadesh [Constantinople – Auth.], Semira [Smyrna, or the modern Izmir – Auth.] and Arad [Arad in Romania – Auth.] are laid under tribute.

In 31: the seventh campaign against the Ruthens [possibly, Southern Russia in this context – Auth.]. The king reaches Nakharain [the Nogai River? Or could it be the Rhine in Germany? – Auth.], installing two memorial stones next to the river. Contribution is paid by the following cities and lands: Anarut [possibly, Italian Turin read in reverse – Auth.], Ni [? – Auth.], Lebanon [Albania – Auth.], Singara [the Holy Mountain? Zion? – Auth.] and Kheta [the Goths; possibly, Germany – or Crimea, which was also within the Ottoman Empire’s domain of influence – Auth.]. Nubia and Ethiopia offer their tribute as well.

In 32: the 8th campaign against the Ruthens in order to collect tribute – among others, it is paid by the King of Assur [or, alternatively, Prussia/southern Russia – Auth.].

In 34: the 9th campaign against the Ruthens [Luthens, or Latins = Western Europe – Auth.] and the Tsakhi [the Czechs – Auth.].

The king of the island Acebi (Cyprus) pays a tribute. Nubia and Egypt also serve the tribute that they are taxed. (If according to Brugsh, Egypt pays tribute, then the pharaoh-sultan already sits in Constantinople-New Rome - Auth.)

In the 35th year: the 10th campaign against the land of Tsakha (CZECH - Auth).

In the 36th year: the 11th campaign.

In the 37th year: the 12th campaign.

In the 38th year: the 13th campaign.

The land of Tzachi (that is, Czech - Auth.) pays a tribute, same as the island of Acebi (Cyprus) and the king (of lands) of Arrekh (Jerich) (the Latin REX, that is, the king?). Ethiopia and Nubia are among the tributaries.

In the 39th year: the 14th march into the land of Ruten. The recovery of the tribute from the Arab-Shaz (? - Auth.) And from the people of Tsakha (CZECH - Auth).

In 40: the 15th campaign against the Ruthens” ([99], pages 340-341).

What was the “ancient” Egyptian custom of conquering cities? We learn of the following: “Enemy cities were first offered the option of surrender. Surrendering cities were treated amicably, and only needed to pay a moderate tribute. Alternatively, the city was taken by storm, with a heavy tribute laid upon its inhabitants. Repeated attempts of resistance led to the destruction of cities and plantations, as well as taking hostages and increased wartime taxation” ([99], page 341).

This is a description of a “Mongolian” custom already known quite well to us, qv in CHRON4.

5.7. A list of cities conquered by Thutmos (Mehmet).

Brugsch: “The king’s first campaign against Upper Ruthen [Latinia = Western Europe – Auth.], whose memory is recorded on many a monument, was the most important and significant campaign of all. Recollections of said campaign cover most of the temple’s walls, and even the pylons were covered in names and drawings of the conquered cities and nations” ([99], page 328).

Brugsch proceeds to quote a list of 119 cities whose inhabitants were taken captive by the “ancient” Pharaoh Thutmos = the mediaeval Mehmet II.

Egyptologists have long noticed the fact that the list is very similar to the list of cities conquered by Joshua son of Nun, the Biblical warlord. Brugsch’s book cites parallels between the names of cities conquered by Thutmos and their names in the Bible (or Book of Joshua, to be more precise – see [99], pages 329-333).

Therefore, the Bible and the “ancient” Egyptian chronicles appear to be referring to the same towns and events. The Biblical Book of Joshua, whose final edition came out in the XVI century A. D., could easily contain renditions of XV century events. See more on the conquest of the promised land by Joshua = Thutmos in the XV century A. D. in CHRON6.

Apparently, our analysis meets previous research of N. A. Morozov here, and concurs with it perfectly. N. A. Morozov discovered it a long while ago ([544]) that many of the cities listed in the Book of Joshua as the cities that he had conquered can be identified as Western European cities that exist until the present day – European cities in particular. See Morozov’s “Christ” ([544]) and our brief rendition thereof in CHRON1, Chapter 1:9.

The above is in ideal correspondence with our reconstruction, since Thutmos = Mohammed had indeed fought in Europe initially.

However, it is still early to part way with the list of cities. The matter is that a detailed analysis of the list itself as well as it title as written in stone makes us doubt that the list consists of the cities conquered by Thutmos exclusively. It is more likely that we are confronted by a list of all more or less significant European centres of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire of the XV century, which weren’t merely taken captive by the Ottomans, but actually participated in the conquest themselves in order to re-conquer the colonised lands.

For instance, the “ancient” Egyptian stone chronicle declares the following (in Brugsch’s translation): “This is a list of the Upper Ruthen’s inhabitants taken captive by His Holliness in the enemy city of Megiddo. His Holiness took their children away to the City of Ous [apparently, an Etruscan city – Auth.] in order to fill the house of his father Amon, Lord of Apeh [Italy, the Apennines or Apulia, qv above – Auth.] in his first victorious campaign” ([99], page 329).

Brugsch’s translation is difficult enough to understand. Did the king really take the citizens of 119 cities captive in the conquest of a single city? This doesn’t seem likely to us, especially given as how he’s supposed to have taken their children away as well. Did the children of 119 cities gather for the battle, too? Further text clarifies the true meaning of the narration. Apparently, what we see is an account of a migration – namely, the colonization of Apeh (Apa), which, as we understand now, probably identifies as Italy or the Apennines. This colonization is the result of the first campaign – one that the pharaoh was only preparing for around the time in question.

We suggest a different interpretation of this lettering. Apparently, Thutmos, or Mehmet, collected the inhabitants of 119 cities that were under his command in order to populate the conquered Italian lands – in other words, he needed them as settlers after his new conquest.

Since the Great = “Mongolian” Empire covered vast amounts of land, this list of 119 cities includes the inhabitants of different parts of the world, Russia (or the Horde) being no exception.

Let us now provide a few examples of easily identifiable cities, whose inhabitants settled in Italy and in the Western Europe in general after the conquest of the XV century ([99], pages 329-333). The Pharaoh may also have given orders for the actual inhabitants of the Western Europe to relocate – for instance, from the seaside areas of Italy towards the centre of the peninsula. And so, the settlers hailed from the following cities:

Kadesh = Constantinople.

Maketa (Megiddo) = Macedon

Libina (Lybna) = Albania.

Maroma (Merom) = the Sea of Marmara and its environs, or Byzantian.

Tamasku = Damascus. Brugsch agrees with us here.

Byzant = Byzantium.

Mosech = Moscow.

Kaanau = the Khan’s Land.

Alan = the Alanians.

Makut or Makeda = Macedon again.

Atamem (Adamaim) = Atamania, or the Ottoman Empire.

Kazuan = Kazan.

Taanak = Tana or Azov (the Danube).

Riaima = Rome (Romea?)

Kenut = Genoa in Italy, mentioned twice.

Luten = Ruthenia, or Russia.

Ribau (Ravva) = Ravenna in Italy.

Saltah (Tsartan) = Land of the Sultan.

5.8. The Muscovite Kara-Kitais mentioned in the “ancient” Egyptian lettering.

The lettering carved in stone that describes the life of Pharaoh Thutmos’s military commander, a certain Amenemkhib, claims that he took part in a war of some sort – possibly internecine, against “the people of Kari-Kai Mesh” (99], page 335). This is an obvious reference to the Muscovite Kara-Kitais, already well familiar to us.

It is likely that the “ancient” stones of Egypt have also recorded the memories of one of the Cossack Ottomans (Atamans) who fought in the Horde (or Russia), right next to the city of Moscow.

5.9. The land of the Russian Khan in Italy.

Another interesting fragment of an “ancient” Egyptian papyrus is as follows: “Likewise, you know not the name of Khanrots in the Land of Aup; it is a bull standing at his borders: also, it is the very place where they watch over the battles between all the strong men (knights)” ([99], age 339). Brugsch adds that the land of Aup “borders with the Khalu nation, or the Phoenicians” ([99], page 339).

This is obviously a reference to the land of “the Russian Khan” (Khan-Rots) located in Aup, or in Italy (the Apennines, qv above). We see a reference to France (Khalu = Gaul), which lies nearby, and Phoenicia (Venice), an even closer state.

Therefore, what we see is a fortunately preserved excerpt from a chronicle of the XIV century conquest of Italy by the “Mongols” = the Etruscans.

5.10. The land of Kitti = Phoenicia, a. k. a. Venice, a. k. a. Scythia.

Kitti ([99], page 308) or Ket ([99], page 320) is mentioned among the countries conquered by Pharaoh Thutmos. Egyptologists identify it as Phoenicia ([99], page 234) – Venice, in other words, as we understand now. In general, the fact that the “ancient” Phoenicia identifies as Venice was discovered by the authors of the present book a long while ago during our study of the mathematical and statistical parallelisms inherent in the lists of the ancient dynasties, qv in CHRON1.

Brugsch quotes other names of Phoenicia, or Venice – Khar, or Khal, reminding the reader that its land “stretches out so far as to reach Aup” ([99], 234). Everything is perfectly correct – the lands of Venice were indeed located on the Apennines and close to the land of the Gauls (referred to as Khal here).

On the other hand, just as one should have assumed from the very start, the initial, or most ancient name of Phoenicia was Kepha, Keft, Khephet and Kephtu ([99], page 234). We instantly recognise it as the name Kita or Kitti – Scythia, that is. Therefore, Egyptologists themselves help us understand the fact that the “ancient” Phoenicia was populated by the natives of Scythia, or Russia (the Horde).

All of the above corresponds to our reconstruction perfectly well – Russia, or the Horde, swarmed Italy in the XIV century A. D. (not B. C.!), leaving it populated by the Etruscans and full of Scythian toponymy.

5.11. The “ancient” Egyptian text of the Kara-Kitai king.

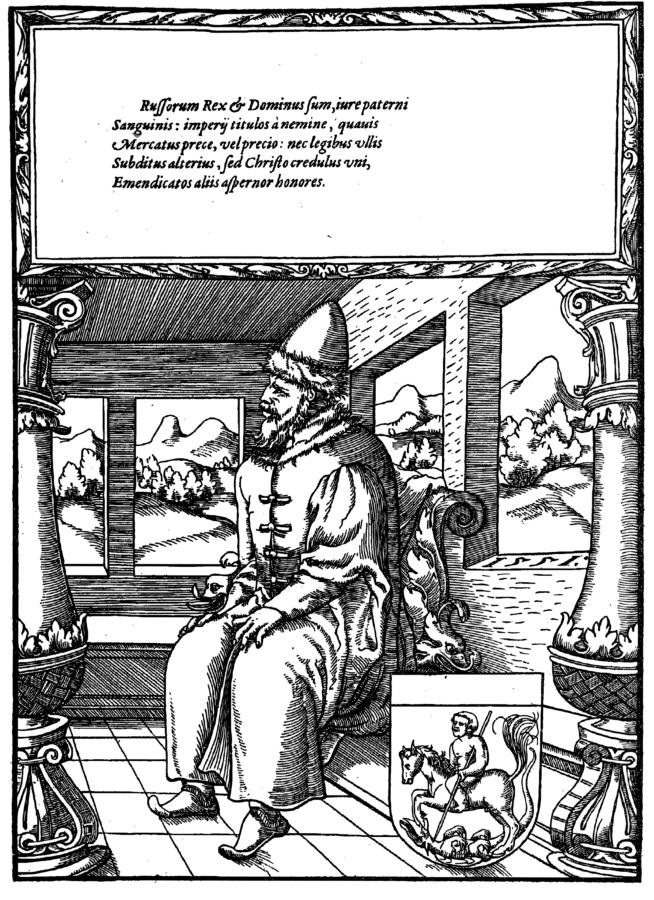

We know of a papyrus ascribed to Pharaoh Sesotris I, who is said to have lived 2000 years before our era ([1447], page 254). The lettering is presumed to have initially been carved on a stele or a wall in Heliopolis – the original didn’t survive. In the epoch of the 18th dynasty it was copied to a leather scroll, according to the Egyptologists, and several more copies are believed to have been made since then. As a result, it has reached us as the papyrus entitled “Berlin 3029” after the place of its storage.

The text in question was written on behalf of the Pharaoh, who claims the following: “I shall give a firm law to Kara-Kitai (Harakhty) . . . I am a king by birth, a suzerain appointed by no human authority . . . I was raised to be a conqueror; the land is mine and I am its ruler” ([650], pages 116-117; also [1249]).

It would be interesting to compare this passage to the words found on the portrait of Vassily III, the Russian Czar, quoted by the mediaeval traveller Sigismund von Herberstein in his famous “Notes on Muscovite Affairs” ([161], page 69; see figs. 20.5 and 20.6). The words are as follows: “I am Czar and ruler by birthright; I asked no one for my royal title, nor did I buy it from anyone – there is no law to make anyone my superior. But, trusting in no one but Christ, I reject the rights begged from others” ([161], page 69).

This formula of the Russian Czar (or the Czar of the Kara-Kitais, as we know already) coincides with the “ancient” Egyptian formula of Sesostris I, the “ancient” Kara-Kitai Pharaoh almost word for word. Let us reiterate that the name “Kara-Kitai” is most likely to be a slight corruption of “Czar of Kitai” – “Czar of Scythia”, in other words.

5.12. Lists of valuables given as tribute to Pharaoh Thutmos by the Europeans.

Let us recollect the fact that the countries of the Western Europe paid a great tribute to Russia, or the Horde, and the Ottomans = Atamans in the XIV-XVI century. It is significant that the lists of valuable objects collected as tribute have survived until our very day known as “tribute lists of the nations conquered by Pharaoh Thutmos”. They can be read on the stones of the “ancient” Egypt. Let us take a short look at them.

Tribute paid by the Land of Kitti (Phoenicia), or Venice – see [99], page 308.

“(And so the children of the kings came close) to the Pharaoh and brought forth their gifts: silver and gold, blue and green gems, and also wheat, wine in skins and fruit for the king’s warriors, since each one of the Kitti nation [Phoenicians or Scythians – Auth.] took part in collecting the supplies needed for them to return to their homeland.

And the Pharaoh forgave the foreign kings . . . [a chiselled-off fragment] . . .

List of items paid as tribute.

3401 live prisoners.

83 hands [workers, or craftsmen? – Auth.]

2041 mares.

191 foals . . . [a chiselled-off fragment] . . .

1 gilded chariot, formerly belonging to a royal foe, and a golden carosserie.

(31) chariots gilded with the gold of the kings . . . [a chiselled-off fragment] . . .

892 chariots of their paltry warriors” (99, page 308).

One must think that the word poetically translated by Brugsch as “chariot” must have simply stood for “cart” or “aroba” – in case of the king, it may have been a lavishly decorated carriage. Apart from that, the king received the following gifts:

“1 exquisite iron [sic! – Auth.] plate armour, formerly belonging to the enemy king.

1 beautifully wrought iron armour of the King of Megiddo [the Macedonian king – Auth.]

200 armours of their contemptible soldiers.

602 bows.

7 tent-poles, gilded, from the tent of the enemy king.

Apart from that, the Pharaoh’s soldiers took the following loot for themselves:

. . . oxen.

. . . cows.

2.000 doe kids.

20.500 white nannies” ([99], page 308).

As we pointed out above, in certain cases the occurrence of the name Ruthen in the list of tribute-paying countries might refer to the symbolic ally tribute paid to Czar-Grad by Russia (“king of Assur”) for a short while. The corresponding records are as follows.

Tribute paid by the Land of Ruthen.

This is a list of items paid as tribute by “King Assur” ([99], page 310) “of Ruthen Land in the year of 32” ([99], page 310).

The following items are listed: 3 pieces of authentic lapis lazuli with indications of their weight (from Babylon), and many vessels of Kherteth stone from Assur. Apparently, the above is a reference to the semiprecious stone from the famous Ural region in Russia.

“A list of items paid as tribute to the king by the Land of Ruthen.

The tribute of King Assur [apparently, the Russian king – Auth.].

Hand clasps from Masq [Moscow! – Auth.] and Makhu leather [furs – cf. the Russian equivalent, “mekh” – Auth.], the mysterious . . . [a chiselled-off fragment] . . .” ([99], page 311).

One cannot quite escape the thought that the allegedly ancient Pharaoh Thutmos received a pair of fur gloves from Moscow – doubtlessly useful in long campaigns; it occasionally gets cold in Constantinople as well.

What else was there from Russia?

“Chariots with wooden heads.

180 (+ x) ‘akkaratu’ [? – Auth.] . . . [a chiselled-off fragment] . . .

343 chariots [carts or arobas? – Auth.] with wooden yokes.

50 cedars,

190 (trunks) of Meru tree.

205 ‘kanakat’ [ropes, perhaps? Cf. the Russian “kanaty” – Auth.] from Nib wood” ([99], page 311).

Mark that Russia, or the Horde, sent Thutmos construction materials for the most part – timber, cedar wood, possibly also rope etc. The Turks must have been short of timber, hence the assistance of the Russian allies, who had an abundance of timber at their disposal.

Also, the very nature of the other items is likely to indicate their Russian origin, apart of the King’s name, Assur (“the Russian”) – timber, fur gloves as a present to the king – neither gold, nor silver, nor wine. Other lands paid in silver and gold.

Simultaneously, the Sultans (or the Pharaohs) must have fulfilled their duty in accordance with the pact that we mentioned above by handing some of the tribute paid to them by the countries of the Western Europe. This must have been another source of silver and gold used by the Russians (see Chapter 12 above in re the adventures of Western European coins that came to Russia in huge amounts back in the day).

This is the end of the list of items given by King Assur as tribute. Although in the lists to follow a great part of the tribute was “paid by the kings of Ruthen”, there is no mention of “King Assur”, or Russia (the Horde) as such. The list includes the tribute paid by the Tsakhi (Czechs), Cyprus etc. Therefore, the term “Ruthen” (or Luthen) refers to the entire European continent, conquered by Russia, or the Horde, at some point.

Tribute paid by the City of Tunep ([99], pages 311-313) – Tana (Azov or the Danube).

We see a direct reference to the capture of the city with great military spoils taken there – the king of the city, 329 noble knights, gold, silver, gems, iron and copper utensils, slaves of both sexes, lead and white gold.

Spoils taken in the land of Tsakhi (the Czech Kingdom).

This country was captured by the Pharaoh. The spoils include slaves, mares, silver dishes, honey, wine, copper, lead, different stones, fruit and cord. Incidentally, “the warriors [of the Pharaoh – Auth.] got very drunk there, and anointed themselves in aromatic oil” ([99], page 313). A most realistic description indeed.

The Pharaoh launched yet another punitive expedition at the city of Kadesh (Constantinople), and his army marched towards the city of Tsamar (Semira) thence – probably, Romea, or Romania, since we learn that he came to the city of Artut = Arad, which we already managed to locate in Romania. However, the name of the city stems from the word “Horde”, and must have been given to the city even earlier – during the previous conquest of the XIV century, known as the Great = “Mongolian” Conquest.

Next we learn of 490 captives taken “at the city of An-an-Rut, which lies at the shore of Lake Nes-Ro-An” ([99], page 490). Let us remind the reader that Roan (Rhone) is simply a synonym of “river” – therefore, we need to find “lake or river Nes” – indeed, we have the river of Lusatian Neisse, or Luzicka Nisa, that flows into the Oder.

This river (Lusatian Neisse) must have been mentioned in the “ancient” Egyptian text, which is presumed to date from the XV century B. C. The word “Luzicka” transformed into “lake” after it was translated from the hieroglyphs (cf. the Slavic “luzha”, which stands for “pond” or “puddle”).

It goes on in this manner – we shall cease our list of items paid as tribute to Pharaoh Thutmos here, since everything is more or less clear to us in general – as for smaller details, there are lots, but their analysis requires a special dedicated research.

As we have seen, the “ancient” Egyptian history can now start telling us more and more new and interesting details, not merely about the life of Egypt, but also – and, possibly, even primarily, about the life of Europe and Asia.