Part 1.

Russia as the centre of the “Mongolian” Empire and its role in mediaeval civilization.

Chapter 2.

Russian history as reflected in coins.

1. A general characteristic of Russian coinage.

Today it is commonly assumed that, upon finding an old coin, numismatist historians are usually capable of estimating where, when and by whom it was minted, either right away or after giving it some consideration. Unfortunately, this is very far from being true. A. D. Chertkov, a famous Russian historian and numismatist of the XIX century (1789-1858), wrote the following: “The appearance of old Russian coins, generally speaking, can usually tell a numismatist nothing about the time of their creation, or their value, or even their names – they are small, and the marks upon them are so poor in quality that even we have dozens of identical coins at our disposal, it is sometimes barely possible to read the lettering upon it, making it out from two or three letters that have survived here and there. Our search for explanations shall be fruitless, whether we turn to the Chronicles, the Deeds or even Karamzin’s ‘History’ – everything is silent . . .

The few lines found in Herberstein’s work, which is truly the Ariadne’s thread in the labyrinth of Russian numismatic knowledge, refer to the coins of his own epoch (the early XVI century). Any connoisseur of Russian coins, having made the effort of reading a prince’s name upon a coin and without any knowledge of the time, the place and the value thereof must use his own conclusions to fill the gaps” ([957], pages V-VI).

Further also: “Let us assume that the entire inscription reads ‘Great Prince Vassily”, for instance, since the coin reveals no more; who could this Great Prince be, who was his father, when did he reign? . . . The same happens with other coins and the names we read upon them – Mikhail, Ondrei, Dmitrey etc. Dozens of princes with such names are known in history. But if the lettering says ‘seal of Great Prince, princely seal, pool (such-and-such), what sort of patience will not cave in?” ([957], pages VII-VIII).

“In 1780, Prince Shcherbatov classified Russian coins as follows:

a) unidentified ones without any lettering,

b) unidentified ones with Tartar lettering,

c) unidentified ones with lettering in Tartar and in Russian,

d) unidentified ones with Russian lettering, and

e) identified coins” ([957], page VIII).

Needless to say, “identified coins” don’t date any further back than the end of the XVI century A. D. Again and again we run into the same threshold of great importance – the beginning of the XVII century. It separates the more or less known history of the XVII-XIX century from the history of Russia as the Horde, or the XIV-XVI century, which was distorted by the Romanovs.

The coins of the Golden Horde were very common in Russia – one often comes across coins with one of the sides allegedly copying a Horde coin.

A. D. Chertkov proceeds to tell us the following: “Unfortunately, authentic Arabic inscriptions are few and far between; most of them do little but imitate the coins of the Tartars . . . even the most diligent Orientalist cannot read the lettering upon them” ([957], page 6).

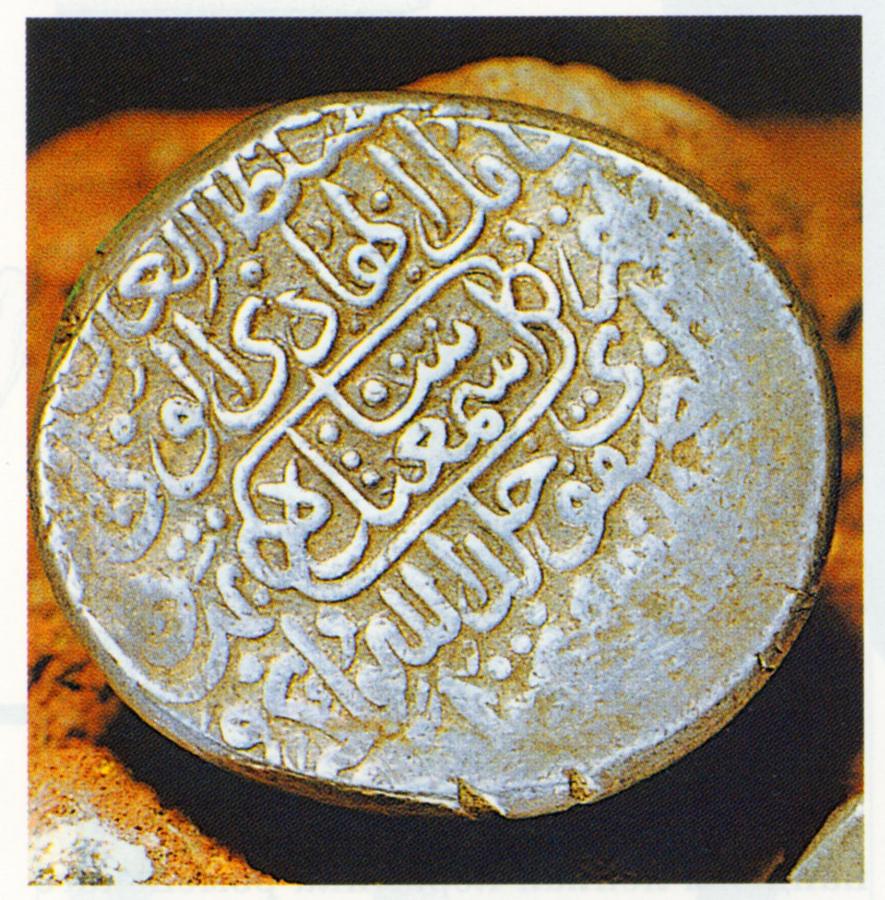

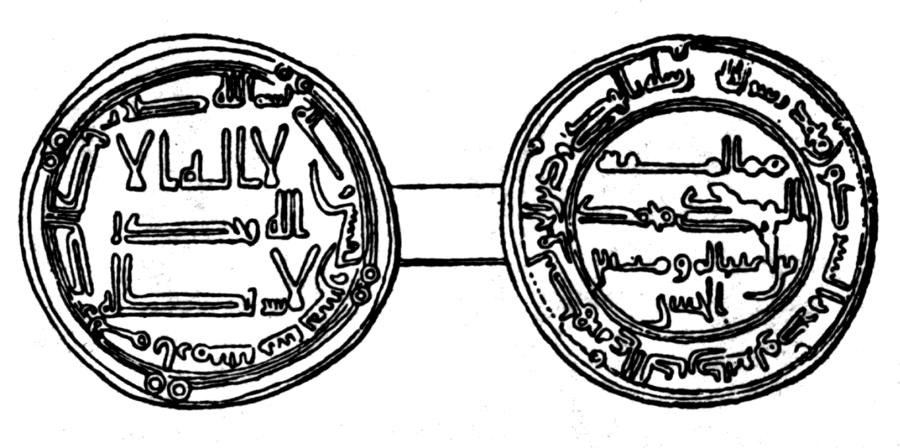

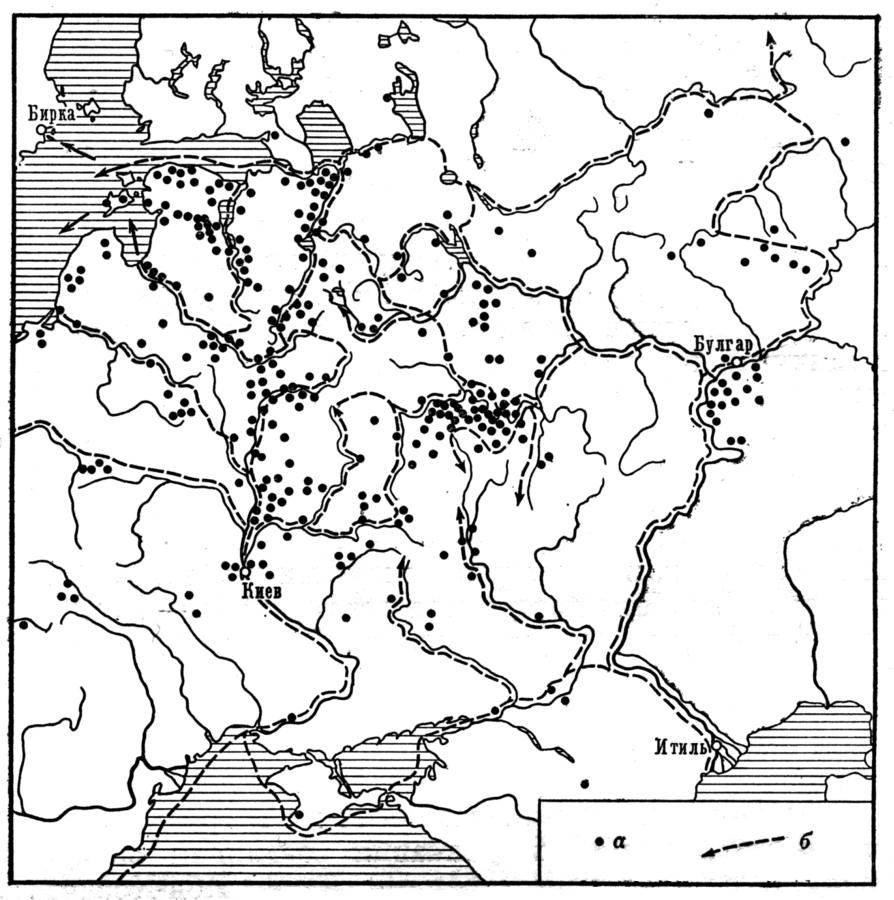

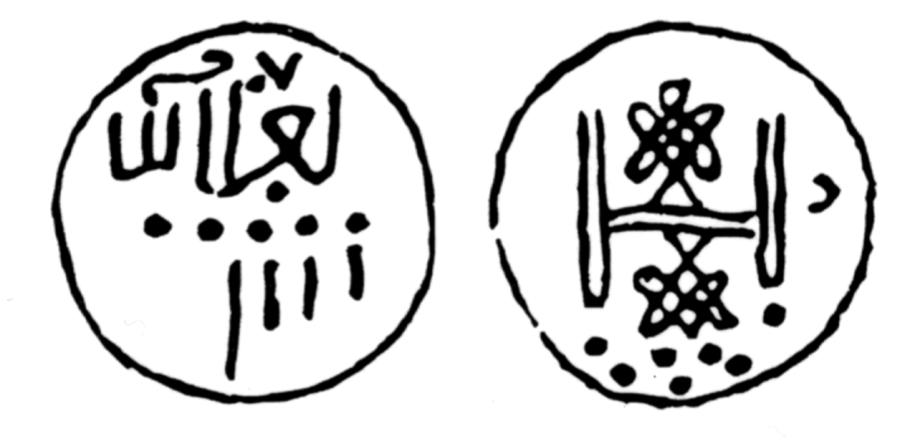

The real picture is as follows. There are lots of Russian coins with Arabic lettering present thereupon; however, historians prefer to believe that most of them are mere “thoughtless copies of Arabic originals”, although numismatists themselves recognize the fact that “authentic Arabic lettering” is also present on a number of Russian coins, qv below. In fig. 2.1 we see one of the “Arabic coins” that were circulating in Russia. Nowadays we are told that the Russians used to use foreign coins in that epoch – Arabic for the most part, due to the alleged lack of domestic coinage. In fig. 2.2 we see a typical “Arabic dirham” of the type frequently found in Russian hoardings of coins ([578], Book 1, page 86). It turns out that nearly the entire territory of Russia and the Eastern Europe yields findings of such “Arabic coins”. In fig. 2.3 we see a map compiled by numismatists, with black dots marking the “hoardings of Kufic coins” ([233], page 89). As a matter of fact, the word “Kufic” may be derived from the Russian word for “buy”, namely, “kupit”, bearing the mind the frequent flexion of the sounds P and F. The word “kupets” (the Russian for “merchant”) might also be a version of the word “Kufic”.

Fig. 2.1. Mediaeval Russian coinage. These coins bore Arabic lettering. It is assumed that the Russians used foreign coins of Arabic origin since they had no coinage of their own. Many hoardings of such coins were found in the area of Vladimir and Suzdal. According to our reconstruction, the coinage in question is authentic Russian coinage of the XIV-XVI century. Historians fail to realize that Arabic was one of the official languages spoken in the Russian Empire, or the Horde, up to the very end of the XVI century. Taken from [331], Volume 1, page 12.

Fig. 2.2. “Arabic dirgham. Found in a Russian hoarding” ([578], Volume 1, page 86). Taken from [578], Volume 1, page 86, illustration 70.

Fig. 2.3. Hoardings of Kufic coins in the Eastern Europe. These hoardings are found in great abundance all over Europe. Taken from [233], page 89.

Furthermore, the lettering on the coins minted by Dmitriy Donskoi is also extremely interesting. The lettering found upon it implies that Dmitriy Donskoi – and even his son, Vassily Dmitrievich, were called “Sultan Tokhtamysh-Khan” in Arabic, no less!

A. D. Chertkov has got the following to say in this respect: “G. Fren has read the following on the coins of Great Prince Vassily Dmitrievich and his father, Dmitriy Donskoi: ‘Sultan Tokhtamysh-Khan, may his years be long’” ([957], page 6). Readers familiar with Chapter 6 of CHRON 4 can appreciate just how much it corresponds to our reconstruction of Russian history.

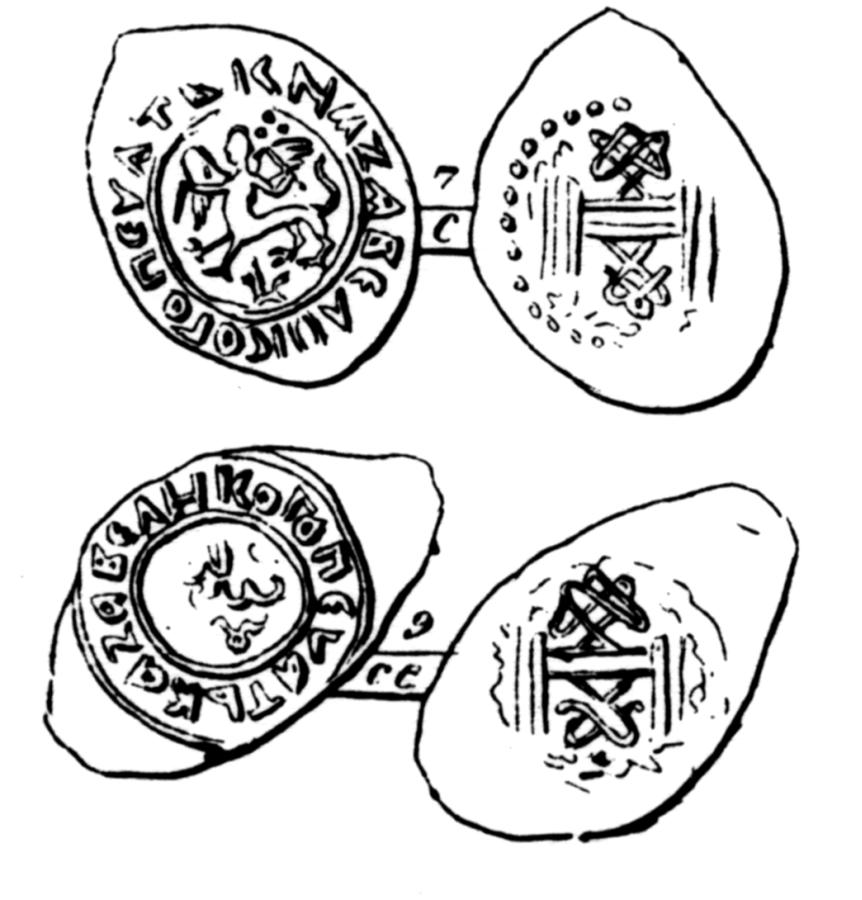

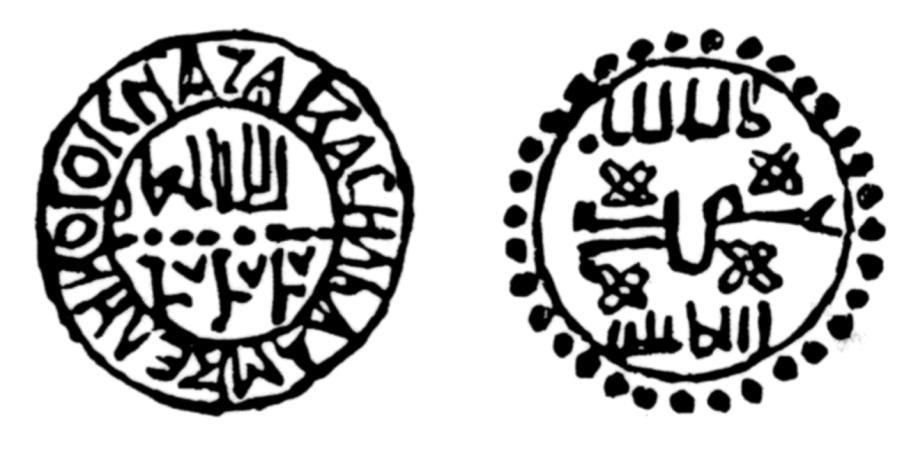

A. D. Chertkov points out that on many Russian coins one often encounters the famous “Tartar seal”. In figs. 2.4, 2.5, 2.6 and 2.7 we see old Russian coins with “Arabic and Tartar” tamgas and “Arabic” lettering. According to A. D. Chertkov, this symbol, “which was very common on the coins minted by the khans of the Golden Horde, can often be seen on Russian coinage of the XIV century, especially that which was minted by Great Prince Vassily Dmitrievich and his brothers” ([957], pages 4-5).

Fig. 2.4. Russian coins bearing the image of a Tartar tamga.

See the right side of the print. Taken from [957], table XVII.

Fig. 2.5.

Russian coin with the image of a Tartar tamga and an inscription in Arabic.

Taken from [870].

Fig. 2.6.

Russian coin with the image of a Tartar tamga and an inscription in Arabic.

Taken from [870].

Fig. 2.7.

Russian coin with the image of a Tartar tamga and

an inscription in Arabic. Taken from [870]. In reality,

the inscriptions considered Arabic today are set

in one of the alphabets used in Russia before the XVII century,

now forgotten. See CHRON4, Chapter 13.

Our opponents might suggest that there’s nothing strange about this fact. The Tartar invaders demanded their vassals that the latter should put the sigil of their conquerors on their coins. This is possible; however, how is one to interpret the following facts?

“Yedigey [presumably, a Tartar khan – Auth.] wrote thus to Vitovt [the alleged Prince of Lithuania, also known as Great Prince Vassily Dmitrievich, according to our reconstruction, qv in CHRON4 – Auth.]: ‘Pay me tribute and put my crest on Lithuanian money’. Vitovt himself was demanding the same of Timur Kutluk-Khan” ([957], page 5).

What do we see here? Khans demand of princes that the latter should put the khans’ crests on their money, and vice versa – the princes demand their sigils to be put on the coins minted by the khans.

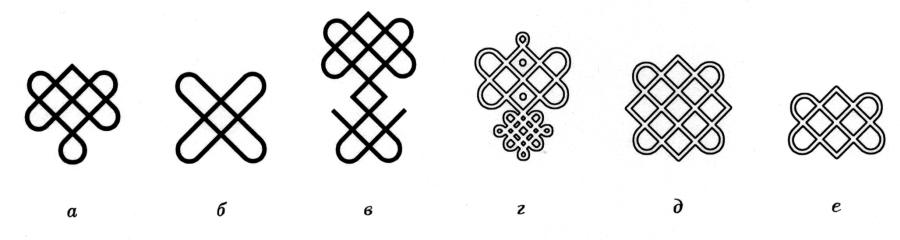

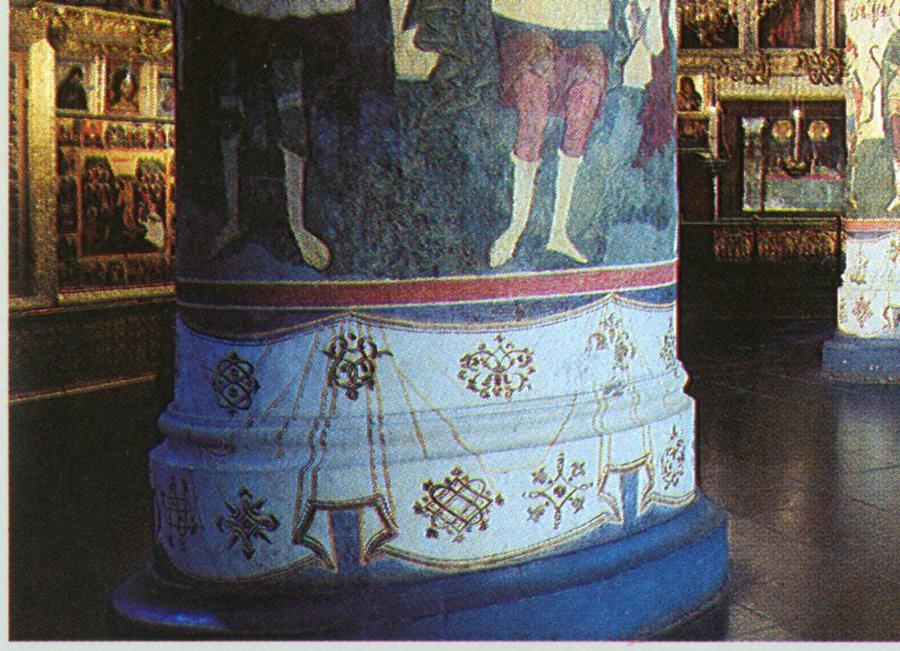

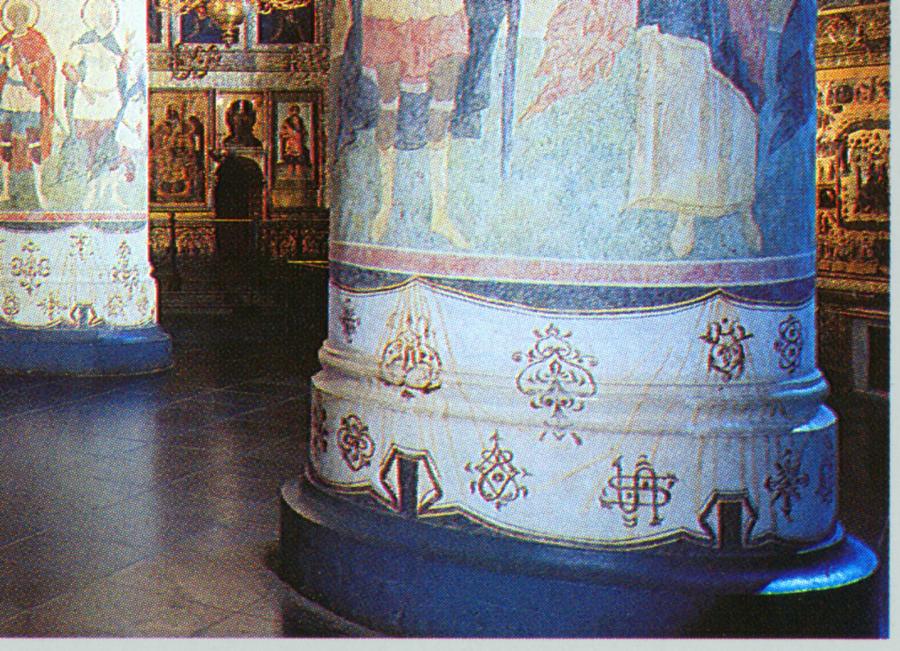

The tamgas are presumed to be of a Tartar origin due to the fact that they were frequently depicted on the coins of the Golden Horde. The book of K. M. Fren ([921]) reproduces some of these coins in its illustrations. Similar crests on Russian coins should signify the dependence of the Russians from the khans of the Horde, presumably foreign, according to the Romanovian and Millerian theory about the conquest of Russia by the “Mongols”. But how are we to explain the fact that virtually the same tamga can be seen on the columns of the Muscovite Kremlin’s Ouspenskiy Cathedral (figs. 2.8, 2.9 and 2.10), where it is even included in the decorative ornamentation, as well as the galleries of Blagoveshchenskiy’s Cathedral of the very same Kremlin?

Fig. 2.8. Various forms of the Horde tamga as found on Russian coins (a, b and c) and ornamental details from the columns of the Ouspenskiy Cathedral in the Muscovite Kremlin (d, e and f). The symbols are obviously related.

Fig. 2.9. Images of Horde tamgas on the columns

of the Ouspenskiy Cathedral in the Muscovite Kremlin.

Taken from [96], page 31, ill. 15.

Fig. 2.10. Images of tamgas the columns of the Ouspenskiy Cathedral

in the Muscovite Kremlin.

Taken from [96], page 21, ill. 15.

Who was whose vassal, then? What are the origins of the crest, at any rate – was it introduced by the khans, the Princes, or both simultaneously?

This oddity is instantly and easily explained by our reconstruction, qv in CHRON4, according to which the khans and the Great Princes were but the same characters, demanding the subservient khans and princes to put their lieges’ crest on their coins. The crest remains the same for both, in this case.

2. The mysterious period of “coinage absence” in Russian history.

According to the Millerian and Romanovian history of Russia, the mintage of coins in Russia started in the X century A. D. – however, it is said to have lasted for a short while (the X century and some of the XI, ceasing in the early XII century).

This is what V. M. Potin, the famous specialist in historical numismatics, writes the following in his book on the history of numismatics in Russia: “The period between the middle of the XII and the second part of the XIV century is usually referred to as the period of no coinage” ([684], page 186).

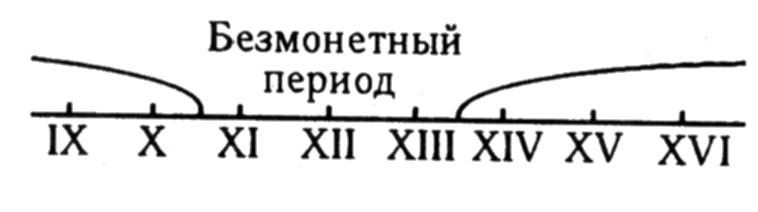

Therefore, Russia is said to have minted no coins of its own for some two hundred years. I. G. Spasskiy, another famous specialist in historical numismatics, even mentions a gap of three centuries and a half inherent in the history of Russian coinage ([806], page 93). This amazing picture is represented schematically in fig. 2.11.

Fig. 2.11. The amazing three hundred years of no coinage in the Romanovian and Millerian history of Russian coin minting.

Moreover, according to V. M. Potin, “V. L. Yanin dates the ‘exclusion’ of coins from Russian currency in the south of Russia to the beginning of the XI century” ([684], page 182). Thus, the epoch of the earliest Russian coinage becomes all but limited to a single century – the tenth, which is followed by a “deathly silence void of coinage” stretched into three centuries and not two.

It turns out that there’s a “modern theory” meant as an explanation of this fact. Historians descant at length about the presumed “rejection of coins” by the ancient Russians – in other words, we are being told that after some brief experimentation the Russians decided they didn’t like the coins, and abandoned them in favour of barter – nails for potatoes, potatoes for fish and fish for nails. We shall refrain from agreeing with this ridiculous presumption. There is another “theory”, according to which the Russians made the instant transition to gold bullion for large deals and banknotes for everyday use, which were made out of leather, according to the hypothesis of learned historians. However, they are surprised to point out that “hundreds of thousands of excellently preserved leather objects have been found . . . without anything that would remotely resemble leather money, regardless of type” ([806], page 69). Therefore, no mythical leather banknotes have ever been found.

The mysterious gap of three hundred years in the numismatic history of Russia has been discussed in literature for quite a while. One comes across comments of this kind: “The methods applied to the dating of hoardings are a much more poignant issue in Russia than in any other European country, since none of them has ever had a “coinage-deprived” period of such length (time when no minted coins were used as currency), except for the territory of the ancient Russia. In the North of Russia, this period began in the 1130’s – 1140’s, and much earlier in the South, stretching up until the restoration of Russian coinage in the second half of the XIV century” ([684], page 182).

Timid attempts to explain the mystical period of “coinage deprivation” in Russian history by references to the Tartar and Mongol invasion are insubstantial due to the very reason that even Millerian and Romanovian chronology dates this “conquest” to the XIII century – circa 1223, which is closer to the end of the period in question than to its beginning.

Therefore, the famous historian I. G. Spasskiy is forced to acknowledge the following in his book entitled The Russian Monetary System: “This period is a very odd and uncommon occurrence in the whole history of Russian currency” ([806], page 62).

The feeling of oddness grows after a closer acquaintance with the coinage period of the alleged X-XI century, covered, for instance, in the monograph of M. P. Sotnikova entitled The Oldest Russian Coins of the X-XI Century ([804]). It turns out that there are some 340 Russian coins of the X-XI century known to date, “75 of which remain undiscovered” ([804], page 5). The mintage is believed to have taken place in Kiev during the epoch of Kiev Russia. For the most part, the coins were minted by Princes Vladimir Svyatoslavich, Svyatopolk Yaropolkovich and Yaroslav Vladimirovich.

The following fact is very interesting indeed: “Minted 1000 years ago, they [the coins – Auth.] have only been known to scientists for 200 years; only 100 years have passed since they were proven to be Russian, and a mere 30 years since it became finally clear that the first Russian coinage is 1000 years old, and not 900-800. The reason is the relatively small number and poor quality of these coins, as well as the scarcity of such findings” ([804], page 5).

Therefore, the real history of Russia’s oldest coins (namely, the coins of Kiev Russia) can only be traced as far back as the XVIII century. Earlier fate of these coins remains unknown; it was relatively recently that historical science “unambiguously dated them to the X-XI century A. D.”

If we are to proceed from the facts that we already know, it is possible to ask the following question loud and clear: do these coins really date from the X-XI century? After all, their dating was based on the pre-existing Scaligerian chronology, which is most likely to be erroneous as we already know. Therefore, the datings of these coins need to be revised. Also, what is the exact meaning of the mysterious statement that “only 100 years have passed since they were proven to be Russian” – were there other opinions? If so, we would very much like to find out about them.

Further immersion into M. P. Sotnikova’s book, or catalogue, strengthens our suspicions about the veracity of datings ascribed to most Russian coins. If we are to believe that the learned historians were correct, and the mintage barely began before this mysterious cessation, it would be natural to expect that it was primitive, rough and showing little experience in general, eventually ceasing because of the inability of Kiev Russia to use coins as its official currency.

It is with great interest that we turn to the catalogue of coins included in M. P. Sotnikova’s book. We see photographs of the oldest Russian coins dating from the alleged X-XI century. What do we see?

We see excellent gold and silver coins of Vladimir. The detail is exquisite, the shape, regular, and many of the coins are in good condition. Svyatopolk’s coins have sustained more damage, but the mintage quality is perfect in their case as well. Next we have the beautifully wrought coins with the legend that says “Yaroslavle serebro” (Yaroslav’s silver). I. G. Spasskiy couldn’t hold himself from the emotional remark about “Yaroslav’s silver coins as a phenomenon of mintage quality that makes them quite special in the context of that epoch’s European coinage” ([806], page 53).

In Scaligerian chronology, this level of artwork emerges all of a sudden, as a flash, instantly demonstrating perfection of craftsmanship. Where are the predecessors of these coins, or the first attempts at minting coins, primitive and crude? There are none, for some reason. It is obvious that the high quality of these coins makes it impossible for them to be the first ones minted in a country that has barely become civilized. They represent a well-developed and rich monetary system with much experience behind it, based on silver and gold.

Later on, after the presumably brief and brilliant surge to amazing heights, we see a total collapse. The mintage of coins ceases, and the coins themselves disappear. We are told that the population of Russia was suddenly cast back to the pre-historic barter system of exchanging skins for iron, iron for honey and honey for skins, entering the “period of no coinage” that presumably covered some two hundred or even three hundred years. Historians suggest all sorts of theories in order to explain this strange phenomenon in Russian history, to themselves as well as the readers.

Let us briefly pretend to trust them and move forward across the time axis, towards the XIV century when Russian coinage was “suddenly revived”.

I. G. Spasskiy reports the following: “In the second half of the XIV century . . . certain Russian principalities revived the mintage of their own coins – silver coinage of all sorts” ([806], page 78). In Moscow, the mintage was commenced by Great Prince Dmitriy Ivanovich Donskoi (1389-1425) in the 1360’s or the 1370’s. The coinage assumed a wider character under his son Vassily Dmitrievich (1389-1425).

I. G. Spasskiy’s catalogue ([806]) reproduces the XIV century coins of Dmitriy Donskoi and his descendants. What do we see?

We see primitive and inelegant coins – small, irregular in shape and made of crude cuts of silver, skewed dies, ugly embossing, obvious cases of dies striking the edge of a silver bar, with nothing but a few letters embossed, and so on. This is indeed the very dawn of real mintage.

These coins are the authentic first coins, and therefore naturally very crude and lumpish; the art of mintage took much time to perfect, and the process had been gradual. Let us move onward through I. G. Spasskiy’s catalogue, advancing chronologically, and consider the coins minted by Czar Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov in the XVII century. Some of them already look satisfactory, with fine enough die detail – however, even here we see a large number of crude coins only marginally different from the ones minted under Dmitriy Donskoi in quality – the same unskilful dies, irregular shapes, and diminutive size.

The conclusion we make is that the real origins of Russian coinage can be traced back to the XIV century A. D. – even if Russians did mint coins prior to that, those were crude and primitive. Russia was therefore little different from all the other countries, since European mintage also doesn’t date any further back than the XI-XII century, qv in the review in CHRON1, Chapter 1:18.

Russian coins of the XIV-XVIII century that have actually reached our age reflect the natural progress of mintage – from the initial crude and primitive coins to the brilliant coinage dating from the epoch of Peter the Great and his successors.

The strange splash of luxurious golden and silver coinage of the alleged X-XI century in Russia receives a simple explanation within the framework of our reconstruction – we are of the opinion that these coins were manufactured on the interval between the XIV and the XVII century. It is clear that they date from the epoch when the craft of Russian mintage had already been well-evolved – gold, silver and excellent dies with fine detail.

These exquisitely wrought coins ended up dated to the X-XI century due to the incorrect chronology of Russian history thought up by court historians of the Romanovian epoch. In other words, the imagination of later historians made the coin travel backwards in time, ending up in the X-XI century due to the chronological shift of 300 or 400 years inherent in Russian history, qv in CHRON4.

Could it be true, then, that Russia was indeed a particularly barbaric state back in those days, one that had barely managed to emerge from the Stone Age? This would give birth to many strange phenomena that couldn’t have happened in the truly civilised countries of the Western Europe. However, this isn’t the case – history of mediaeval European coinage paints the exact same picture.

3. Strange absence of golden coinage from the Western European currency of the VIII-XIII century.

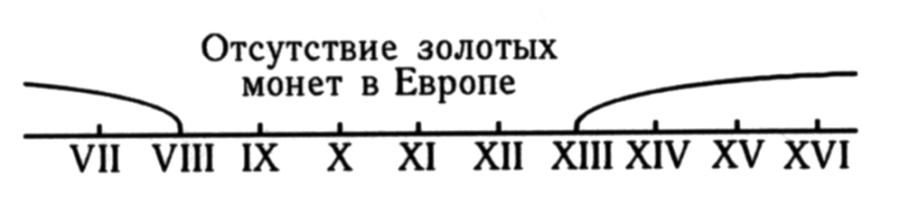

We already mentioned this surprising effect in CHRON1, Chapter 1:18. We shall now complement these observations of ours with several new considerations. It is generally thought that the “ancient” Rome minted golden coins of outstanding quality. The mintage of golden coins had dwindled over the centuries that followed, and is reputed to have completely ceased in the VIII century A. D. This mysterious “disappearance of gold” had lasted until the XIII century, and even the XV in some of the European countries.

This is how V. M. Potin comments on this famous mystery: “Between the V and the middle of the VIII century golden coins prevailed in the currency of many European countries. Between the middle of the VIII and the XIII century golden coins in European countries were extremely scarce, with the single exception of Byzantium and certain European regions that were under the influence of Byzantium and the Orient, where gold and copper had still played an important role.”

Potin proceeds to tell us that “at the end of the X century, golden coins were briefly minted in Russia; they bore the clear marks of Byzantine cultural influence [we have already mentioned this strange surge of masterful Russian coinage in the alleged X-XI century – Auth.] . . . In the second half of the XV century, the mintage of golden coins was resumed after a break of five hundred years by Ivan III, Great Prince of Moscow. The XV century begins the epoch of gold and silver currency” ([684], page 133).

Fig. 2.12. Mysterious lack of golden mediaeval coinage in Europe

in the epoch of the VIII-XII century A. D.

However, in Italy golden coinage is supposed to have “resumed” somewhat earlier – in the alleged XIII century. A propos, the quality of the “resurrected” mediaeval coins dating from the XIII-XVI century is just as high as that of the “ancient” gold dated to the epochs preceding the VI-VIII century by learned historians, qv in fig. 2.12.

Several “theories” were suggested to explain this.

Theory #1. The Dark Ages and the wave of barbarism sweeping over Europe in the VIII-XIII century.

Theory #2. The economical incapacity of Europe.

Theory #3. Shortages of gold etc.

We believe the explanation to be completely different and a great deal simpler. It is as follows: the “ancient” golden coins of the alleged I-VIII century were in fact manufactured in the epoch of the XIV-XVII century. Then they were misdated to deep antiquity by the erroneous chronology of Scaliger and Petavius. New Chronology returns them to the due place and makes the picture a great deal more natural, in particular:

First there were the primitive and crude coins of the X-XII century; later on, as experience grew, the mintage of golden coins began in the XIV-XV century.

It appears as though Russian coinage has been developing more or less simultaneously with the Western European. This is perfectly natural, taking into account the constant trade between the countries, and especially the fact that all of it took place within the boundaries of the united “Mongolian” Empire. Nations were quick with adopting the useful ideas developed by their neighbours and introducing them at home. There were no pronounced leaders or outsiders – all the nations were developing at a more or less constant rate.

Actually, historians themselves mention this fact: “The technique of manual Russian mintage in the XIV-XVII century didn’t differ much from the techniques of the other European countries” ([684], page 165). Further also: “The naissance of Russian coinage [dated to the X century nowadays – Auth.] coincided with the time that the mintage of coins was introduced in a number of European countries such as Poland, Sweden and Norway . . .” ([684], page 231).