Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 19.

“Ancient” African Egypt as part of the Christian “Mongolian” Empire of the XIV-XVI century - its primary necropolis and chronicle repository.

6. A hypothesis: certain major constructions of the "antiquity" were made of concrete.

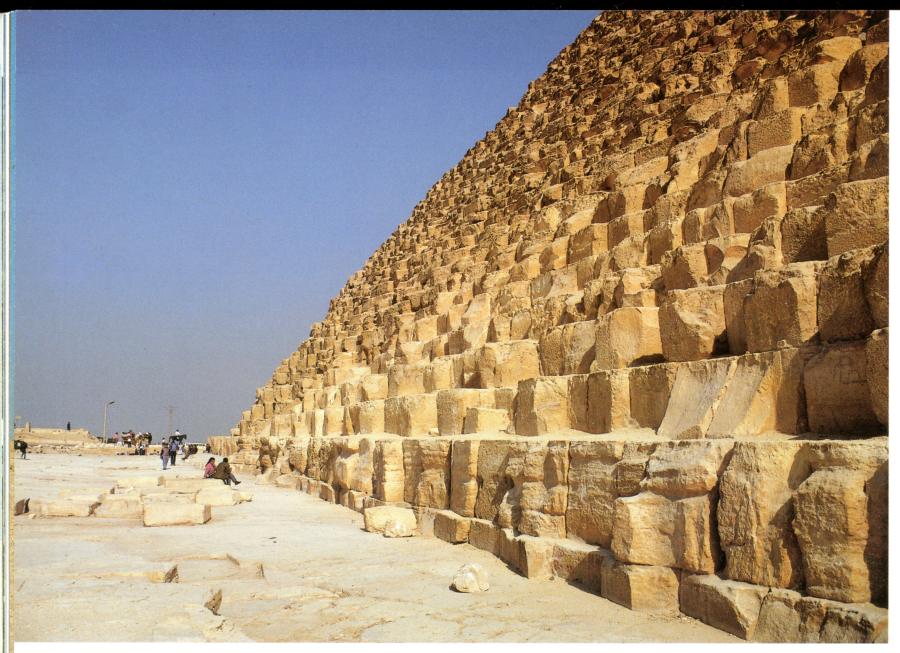

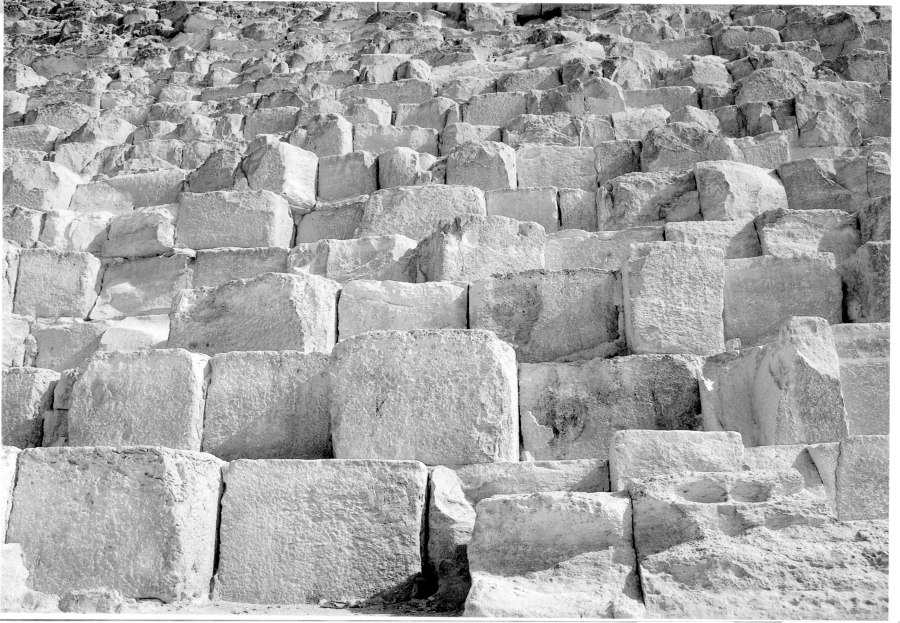

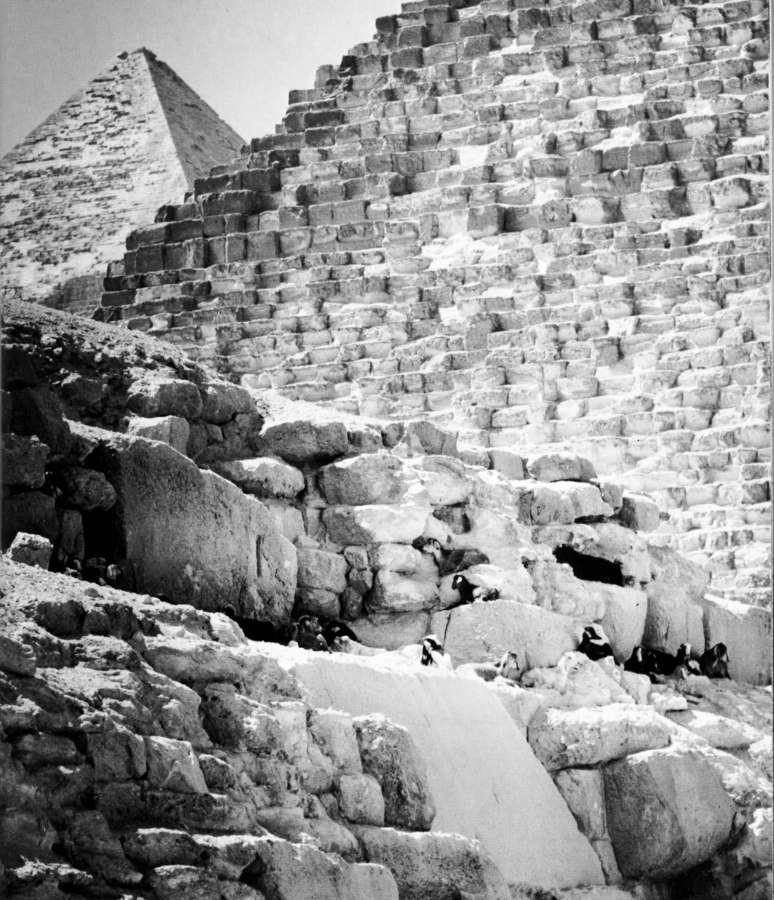

Let us now consider the construction of the largest Egyptian pyramids in Gizeh. We are told that the Egyptian pyramids were built of monolithic stone blocks that were brought from quarries located at a great distance, and piled up against each other in a mysterious way ([99] and [464]). Some of the resulting stone constructions are over 100 metres high; for instance, the height of the Cheops Pyramid equals some 140 metres. In figs. 19.51, 19.52 and 19.53 we see the masonry of the Cheops Pyramid. However, the sheer size and height of these megalithic "ancient" constructions fail to correspond with the capacity of the ancient builders.

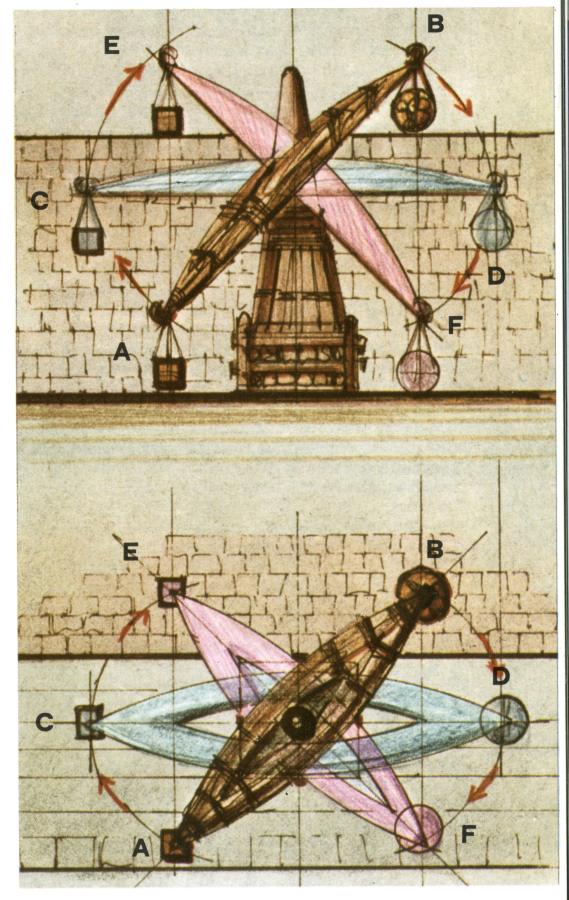

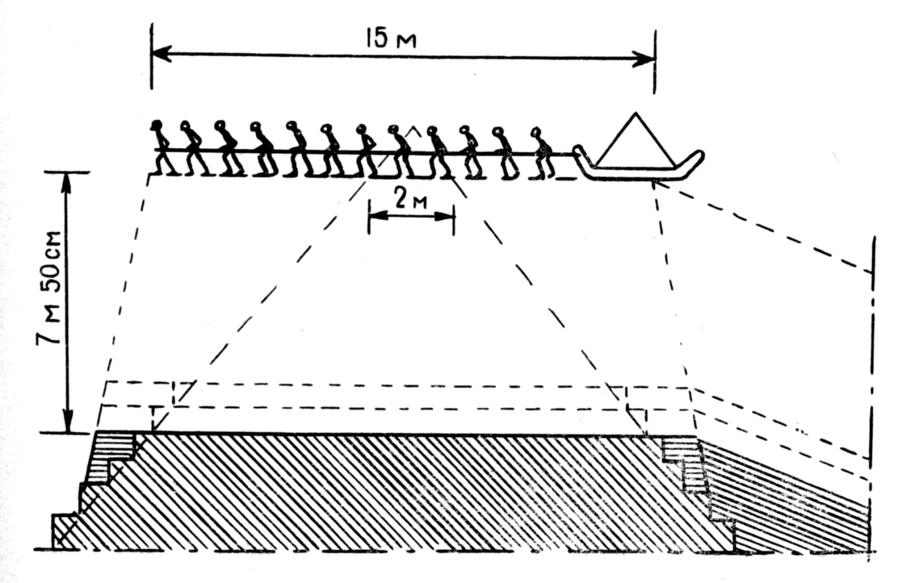

This is the very reason why there are so many different theories aimed at explaining how the enormous blocks were transported and lifted to such a great height. It is assumed that thousands of slaves worked in quarries carving out monoliths weighing between 2.5 and 15 tons and then used "sleighs" for pulling them towards the construction site. Ingenious elevating contraptions were allegedly employed for taking them up - gigantic sand hills of some sort, complicated machinery (such as shown in fig. 19.54, for instance - artistic fantasies through and through). See [464]. One of such amusing "theories" is cited and even illustrated in the book of the famous Egyptologist Jean-Philippe Lauer ([464], page 199; see fig. 19.55). However, all such "theories" remain nothing but fantasy.

This is especially true given that certain pyramid blocks weigh much more than 15 tons - closer to 500, in fact. Lauer naively assumes that the ancient Egyptians "were getting more and more au fait with the transportation of monolithic blocks, which got ever heavier. The limit must have been reached during the reign of Khefren. Hölscher has found blocks whose volume equalled some 50 or 60 cubic metres weighing around 150 tons in the masonry of his pyramid's lower temple, whereas the walls of the upper temple contain a block 13.4 metres long weighing around 180 tons and another one that has around 170 cubic metres in volume and weighs around 500 tons. “It is perfectly obvious that the transportation of such blocks on sleighs is an utter impossibility" ([464], page 189). Lauer proceeds to voice the hypothesis that blocks of this enormous size were moved on wheels. However, it remains a hypothesis and nothing but - and a very dubious one at that. Even in our time the transportation of a 500 tons stone block would be an extremely complex technical task. Indeed, why didn't the "ancient" Egyptians use smaller blocks? All of this remains a mystery to the Scaligerite historians; hence the abundance of books about the mysteries of the pyramids (Lauer's book is entitled "The Mysteries of the Egyptian Pyramids" ([464]).

Yet it turns out that there is no mystery here. The only mysterious fact about the whole affair is how the Egyptologists fail to see that the overwhelming majority of blocks that comprise the enormous Egyptian pyramids, apart from the jacketing and a number of internal constructions, are made of concrete.

Let us explain just what we mean by that. The considerations and facts related in the present section were pointed out to us by Professor I. V. Davidenko (Moscow), Doctor of Geology and Mineralogy.

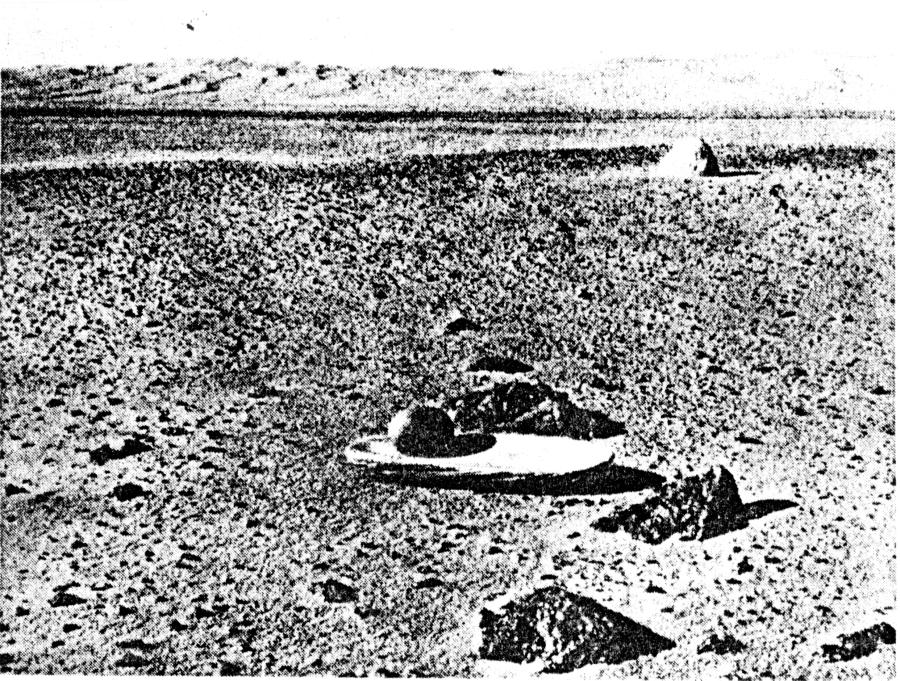

The problem of grinding ores and rocks was solved by the ancients in the exact same way as the problem of grinding grains - they used grain bruisers, mortars and millstones. A. V. Razvalyaev, Doctor of Geology, observed dozens of millstones in the region of the Gebait deposit in the Red Sea Mountains, which were used for the grinding of golden ore and equalled some 50-60 centimetres in diameter. The rock was ground by millstones and taken to the shore of the nearby river, which has dried up by now, for panning. Smaller grinding devices of a similar kind are also known - attrition mills, qv in fig. 19.56; they were discovered in the Egyptian desert.

This simple technology of rock grinding could have easily brought about the invention of concrete. In order to make concrete one needs to grind rock into fine powder; the easiest is to use softer species of rock, such as limestone. There are open deposits of limestone in the famous Egyptian pyramid field. The builders had their source of construction material right next to the site. In order to transform ground limestone into dry cement, one has to dry it really well or subject it to thermal treatment. However, the hot and dry climate of Egypt, where rainfall can happen as seldom as once in five years, special drying procedures were extraneous ([85], Volume 15, page 447). The fine dry powder is then poured into some mould (a simple wooden box suffices for this end), and mixed very thoroughly with water. After it dries, the powder particles remain firmly attached to each other. After a while the mortar solidifies and transforms into stone, or concrete. The powder could also be mixed with pebbles or small stones of roughly the same size, which become "frozen" into the resulting concrete blocks.

The above is a rough description of the mediaeval concrete manufacture technology. After the passage of some time, it becomes almost impossible to tell such blocks apart from stones carved from the same kind of rock since they erode and begin to look like "natural stone".

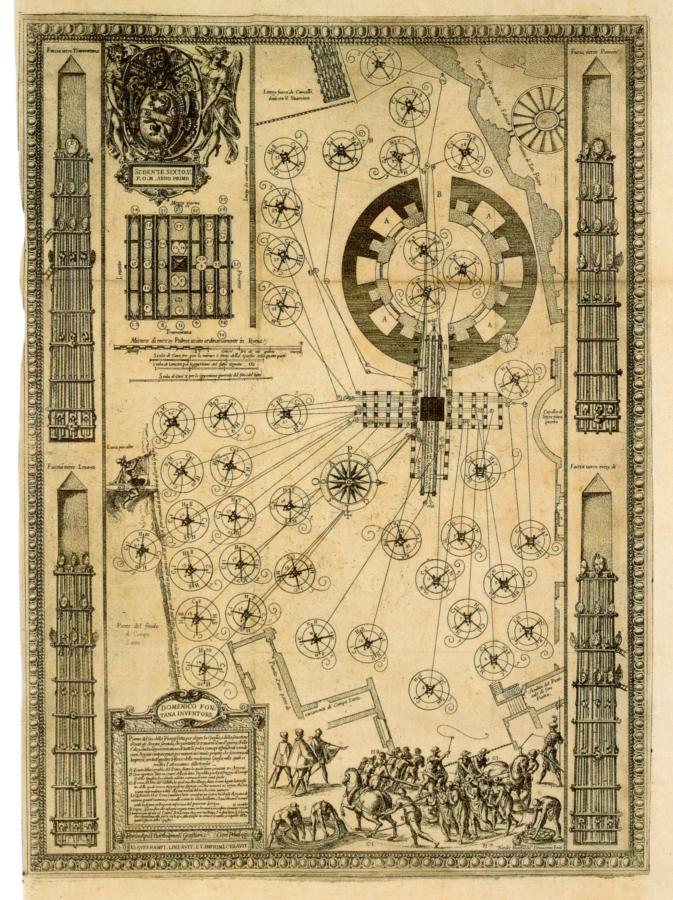

Concrete manufacture is a simple enough process, which means that concrete became a common construction material as soon as it was invented. One must point out the advantages of the "concrete technology" as compared to the construction of buildings from natural blocks of cut rock. The process of carving large blocks of monolithic stone involves enormous complications, since it is difficult enough to transport them across the distance of several kilometres, let alone several dozen kilometres. Of course, such blocks were occasionally used - for instance, the famous Egyptian obelisks found in a number of European cities apart from Egypt could be carved of monolithic rock. There are old documents and drawings in existence that describe the manufacture of certain obelisks, as well as their transportation and installation. However, every such operation would naturally involve a great effort, which is why the manufacture of solid stone obelisks never caught on too widely. In fig. 19.57 we reproduce an ancient drawing that depicts the installation of the Vatican Obelisk in the alleged year 1586 - it is said to have been brought to Italy from Egypt in Africa. We can clearly see that the builders had to invest much effort into installing the obelisk vertically - an extensive system of mechanisms and cables was deployed for this purpose. However, this may also be an invention of more recent artists.

It has been a while since the French chemist Joseph Davidovich, Professor of the Bern University, put forth an interesting hypothesis ([1086] - [1093]). Having analysed the chemical compound of the "monoliths" that the pyramids were built from, he suggested that they could be made of concrete. I. Davidovich managed to define 13 components that could have been used in its manufacture. Thus, just a few teams of the "ancient" Egyptian concrete workers could easily accomplish the construction of a pyramid whose height would amount to 100 or 150 metres, and over a short enough period of time to boot - a lot less than several decades, at any rate.

The problem of powder production could also have been solved without too much effort. A certain number of workers - possibly not that many, could have used primitive millstones or attrition grinders for breaking up the soft rock, which would then be dried, loaded into baskets and transported to the construction site in the conventional manner on mules or horses. Several carriers would lift the baskets with the powder to the top the pyramid under construction, where other workers prepared the wooden casing and filled it with mortar. When the blocks solidified, the casing was removed. The builders would proceed with new blocks, making the pyramid grow. A propos, the manufacture of gigantic blocks should not necessarily imply the use of mortar exclusively; it could be mixed with gravel and pebbles, or whole pieces of natural rock so as to save powder - it's a common practice today as well.

According to Professor I. Davidovich, he managed to read the recipe for the manufacture of concrete in the ancient times, which was transcribed as a hieroglyphic inscription on a stele dating from the epoch of Pharaoh Joser ([1086] - [1093]). The hypothesis of I. Davidovich is occasionally mentioned in popular press. See, for instance, the article entitled "Concrete Pyramids?", which cites the UPI as the source, published in the "Komsomolskaya Pravda" on 27 December 1987. However, as far as we know, historians and Egyptologists still pretend to know nothing of the research of I. Davidovich. The ignorance may also be feigned - or deliberate.

The idea of I. Davidovich allows for a radically new conception of how certain particularly large "ancient" constructions were built. According to our theory, they were built in the XIV-XVII century; the use of concrete during that epoch appears to be perfectly natural and in full correspondence with the mediaeval level of construction technology. The veil of mystery is lifted from the "ultra-ancient" megalithic construction works, which transform into a routine procedure all in all, albeit a complex one.

The idea that the Egyptian pyramids were made of concrete may provoke a variety of reactions. For instance, it can be considered "yet another theory" in a long list of other unsubstantiated theories. We wouldn't write about it in so much detail if it hadn't been for just a single circumstance, namely, the existence of irrefutable proof that the Cheops Pyramid, for one, was indeed made of concrete.

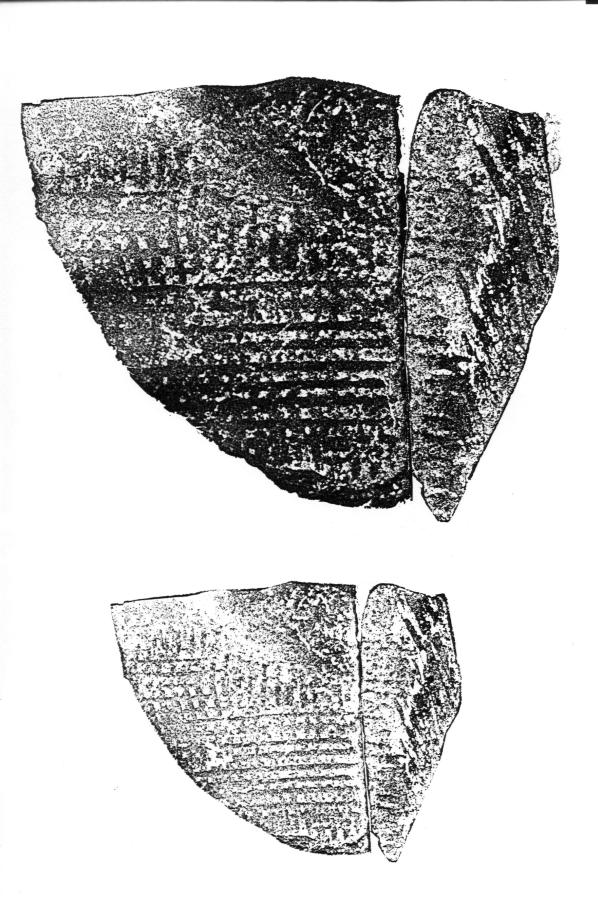

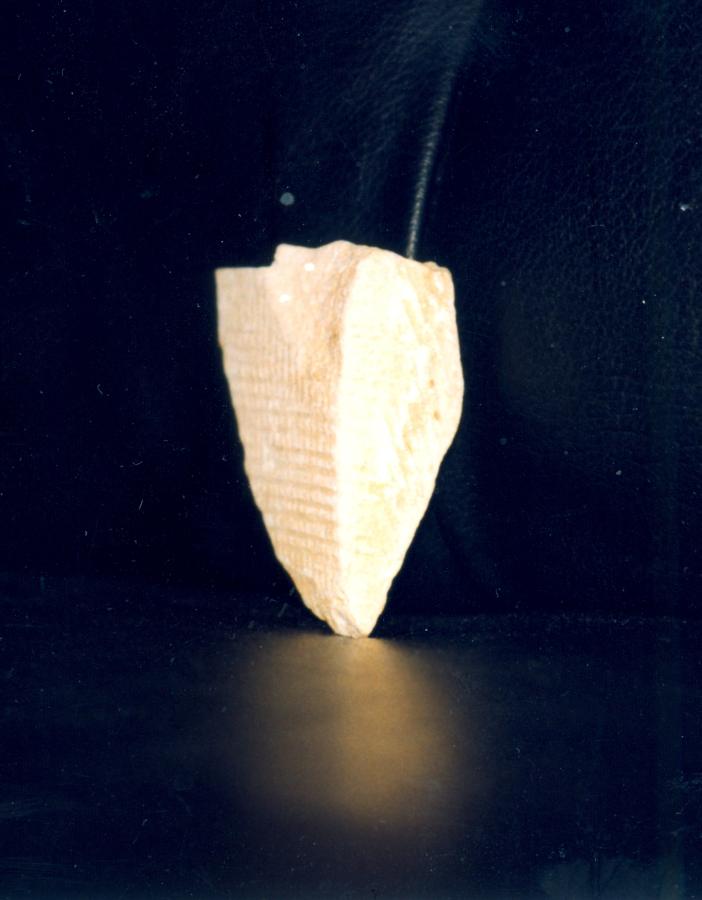

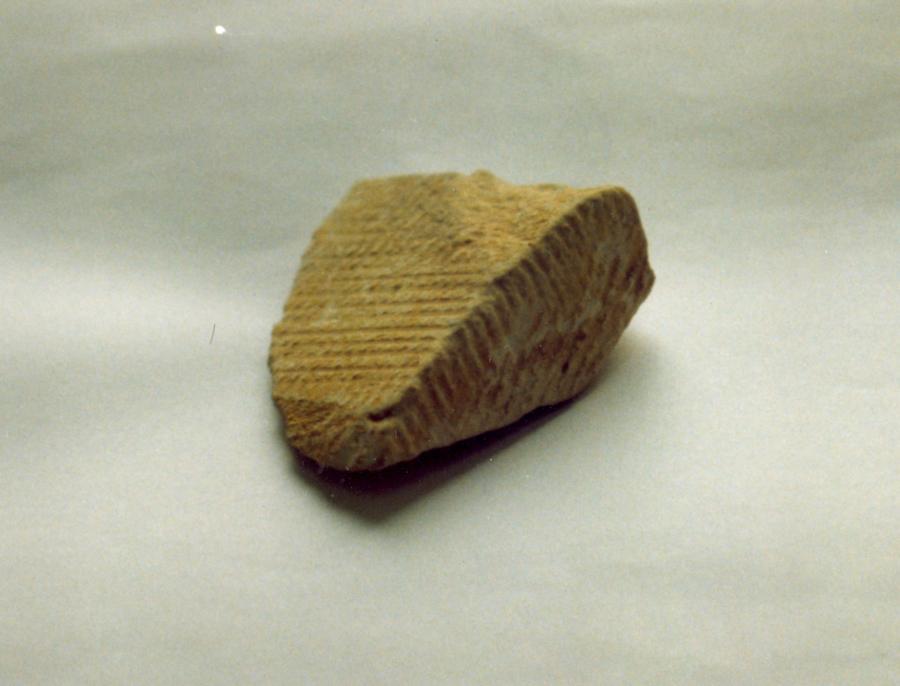

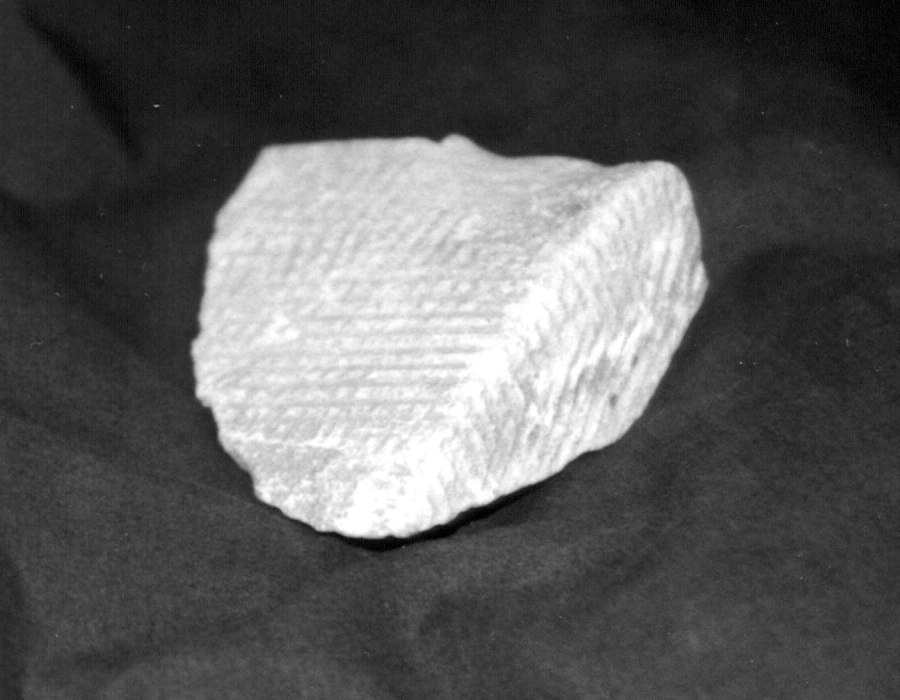

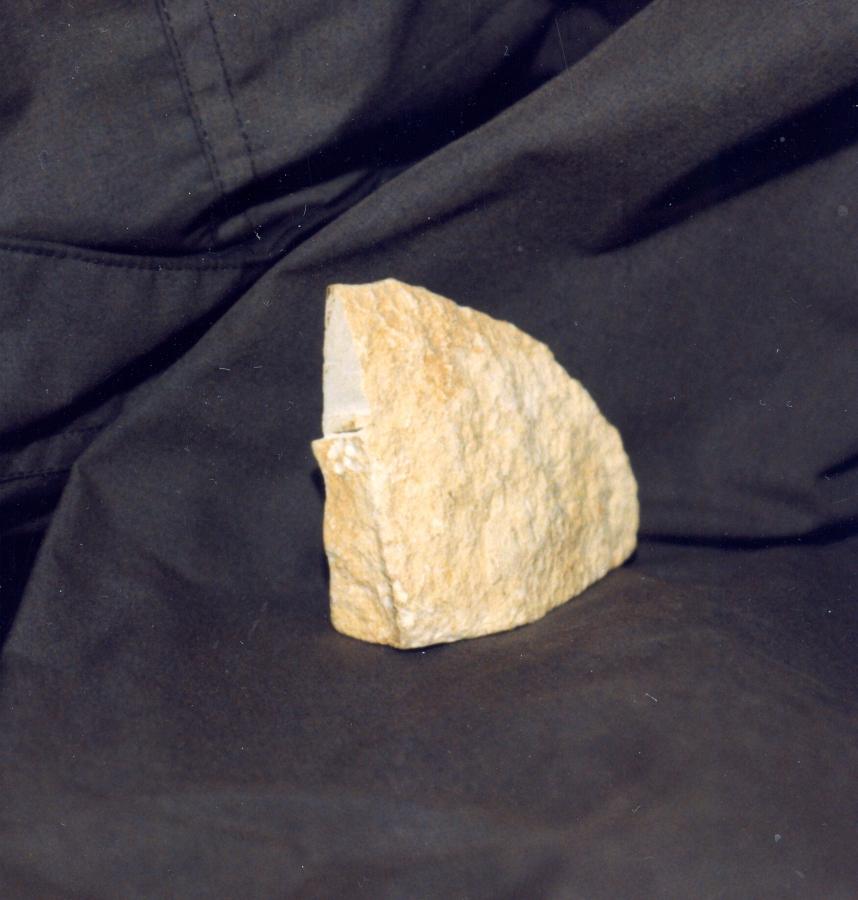

The proof in question is perfectly material - a fragment of a stone block from the Cheops Pyramid taken from its external masonry the height of 50 metres. This fragment broke off a block's top corner. The fragment is a mere 6.5 centimetres long, qv in figs. 19.58, 19.59, 19.60, 19.61, 19.62, 19.63 and 19.64. The fragment was kindly lent to us by Professor I. V. Davidenko (Moscow), who also called our attention to the circumstance that identifies said fragment as a piece of concrete without a shade of ambiguity.

As we can see in the photograph, the surface of the block was covered by a thin net. A careful study demonstrates it to be the mark of the matting from the inside of the wooden casing. In figs. 19.58, 19.59 and 19.61 we can see it perfectly well that the matting was folded at a right angle alongside the edge of the block, with another piece of matting overlapping over it at a short distance from the edge. We can see that the end of the second mat forms a fringe. No transverse threads are to be seen anywhere alongside the edge, they have fallen off the way it happens to the plain edges of the rough fabric used for such matting.

The top surface of the block is very uneven, qv in figs. 19.63 and 19.64. A part of the fragment's top surface was sawed off for chemical analysis. The rest has retained the original knobbly shape. This is just how the surface of a concrete block looks when it solidifies; nowadays special vibrators are used in order to smoothen the hardening concrete surface. The Egyptians of the XIV-XVII century obviously didn't have any such machinery, hence the uneven surface of the blocks. We are referring to the top side of a block - the rest of them are even, but bear the marks of the matting. In case of a carved block, all sides would look the same.

According to the report of our eyewitness, who has chipped a piece off one of the Cheops Pyramid's blocks (he needed to purchase a special licence for this purpose), such matting marks can be seen on every block comprising the section of the pyramid that the fragment comes from. Let us emphasise that the section in question is situated at the height of 50 metres, and pertains to the side of the pyramid that opposes the exit. No tourist groups are usually taken there; the average tourist can only see the bottom rows of masonry from ground level, where one sees no matting marks. They could have been chiselled off deliberately, but not necessarily so - the sandstorms so frequent in these parts carry fine sand that polishes the bottom blocks, which are rather soft - like plaster or a human fingernail. Therefore, sandstorms could have polished the surface of the blocks at the bottom completely, destroying the matting marks from the casing. However, the wind doesn't carry any sand at the height of fifty metres above ground level, and the blocks from that part of the pyramid have retained such marks as a result.

It would be hard to assume that the modern specialists who deal with the pyramids have failed to notice this amazing fact. We believe that the only plausible explanation is that they noticed everything perfectly well, yet remain stubbornly silent, trying to maintain the attractive legend of the pyramids' great antiquity as devised by the Egyptologists. After all, we realise it perfectly well that if the pyramids are actually made of concrete, their age may by no means amount to thousands of years.

Incidentally, this also solves many other "pyramid mysteries" - for instance, the conspicuous absence of cracks from the pyramid blocks. Geologists are well aware that natural limestone has a layered structure, being a sedimentary rock. Therefore it inevitably starts sporting cracks at some point, which run alongside the layers - unlike concrete, which is a uniform and amorphous material consisting of ground and mixed particles and therefore immune to cracking. This also explains the absence of the so-called "tan" on the surface of the pyramid blocks. This "tan" appears on the exposed surface of any natural rock over the course of time - it darkens under the influence of the chemical elements that rise to the surface. This effect is produced by the crystalline structure of natural rock. However, the surface of concrete is virtually immune to the "tan", since the crystals break up when the rock is ground into powder.

This also solves another "mystery" of the Cheops Pyramid. It was noticed long ago that some parts of the Cheops Pyramid such as its inner chambers "have joints so thin that they initially seem to be mere scratches made on the surface of the stone, occasionally being altogether invisible - their width . . . is 0.5 mm on the average" ([464], page 32). The Egyptologist J. P. Lauer addresses the reader as follows, with pathos galore: "Do you imagine the sheer volume of effort took to make blocks fit so closely together, although they often weigh many tonnes?" ([464], page 32). Indeed, it is hardly possible to imagine such a thing, especially given that the top side of the blocks has an uneven texture. We are supposed to believe that a block can be placed on top of such surface in such a way that the gap between them will virtually cease to exist - a block of some 15 tons, no less. Historians don't offer any coherent explanation of this fact - they "aren't interested in such matters".

However, now we see everything fall into place. If the top block was made of concrete on site, no gap could have formed between a given block and the one below it. The cement poured into the wooden casing from the top would naturally reflect the uneven surface of the block below. So where do the "fine gaps" between blocks come from? It turns out that the gaps are really very thin layers of limestone mortar, "which has survived until this day as a barely noticeable line, thin as a leaf of hammerred silver" ([464], page 32). Therefore, the builders of the pyramids were deliberately separating adjacent blocks so as to avoid their concatenation. Prior to moulding a new block on top of the construction, they used a special kind of mortar designed to prevent the blocks from merging together. This was a very reasonable thing to do - otherwise the pyramid would transform into a single monolith without any joints. Such a colossal construction would inevitably crack under the influence of inner tensions as well as the substantial temperature differentials characteristic for this part of Egypt. The only way of avoiding it was to build the pyramid from individual blocks of concrete so that it could "breathe", relieving the forming tensions.

As for the quarries on the other bank of the Nile that exist until this day, as well as the descriptions of how the rock was transported towards the pyramids ([464], page 189), they only relate to the stone jacketing, which had once covered the entire surface of the Cheops Pyramid. Some remains of the granite and limestone jacketing have survived until this very day - for instance, near the top of the Khefren Pyramid.

By the way, early European travellers that visited Egypt also mention cement as part of the pyramid construction. In particular, the Frenchman Paul Lucas, who visited Egypt in 1699-1703 and in 1714-1717, claimed that the pyramid jacketing "was made of cement and not solid stone . . . His work was a great success, and became rather famous. He was the one who introduced the French to the culture of Egypt" ([464], page 58). Modern commentators find this irritating for some reason, and they declare Lucas "an untrustworthy guide" ([464], page 58). However, as we understand now, he was correct, and must have been referring to the pyramid itself and not the jacketing.

Finally, let us turn to Herodotus, the "father of history" - after all, it was Herodotus who had left us a detailed description of the pyramid construction which all the modern Egyptologists use for reference. The amazing thing is that Herodotus clearly reports the use of the mobile wooden casing for constructing purposes - the casting of concrete blocks, in other words ([163], 2:125, page 119). In order to realise this one must simply read his text thoughtfully and attentively: "This is how the pyramid was built. At first, it was built with steps, like a staircase. The stones intended for use in constructing the pyramids were lifted by means of a short wooden scaffold. In this way they were raised from the earth to the first step of the staircase; there they were laid on another scaffold, by means of which they were raised to the second step. Lifting devices were provided for each step, in case these devices were not light enough to be easily moved upward from step to step once the stone had been removed from them" ([163], 2:125, page 119).

Nowadays Egyptologists suggest to interpret the text of Herodotus as a description of some wooden machinery used for the elevation of stone blocks weighing 15 and even 500 tons ([464]). It is perfectly obvious that no wooden devices could be used for this purpose; therefore, historians are forced to consider the report of Herodotus untrustworthy ([464], page 193). Historians suggest the theory of earthen mounds instead. However, the German engineer L. Kroon "uses lengthy calculations in order to prove the impossibility of using such mounds for construction purposes - he believes that their construction would require as much labour as the construction of the pyramid itself, and even in that case the last few metres of the pyramid's top would remain unfinished" ([464], page 194). The book of the Egyptologist J. P. Lauer ([464] dedicates about 15 pages to the problem of raising the blocks to the top of the pyramid (pages 193-207); however, he doesn't provide us with anything in the way of a satisfactory explanation.

However, if we are to read deeper into the text of Herodotus, we shall easily recognise it as the description of the wooden casing used for "lifting" the concrete blocks - casting them step by step, in other words. Herodotus is describing a simple construction - something along the lines of a knockdown wooden box made of short planks, which was filled with concrete. When the concrete hardened, the box would be disassembled and taken to the next step.

What we encounter here is a vivid example of modern historians being reluctant to let go of any theory that made its way into history textbooks once, no matter how absurd. We consider the fear of tampering with Scaligerian chronology to be their primary motivation - after all, if one begins to doubt this chronology, the entire edifice of the "ancient" and mediaeval history according to Scaliger and team falls apart like a house of cards.

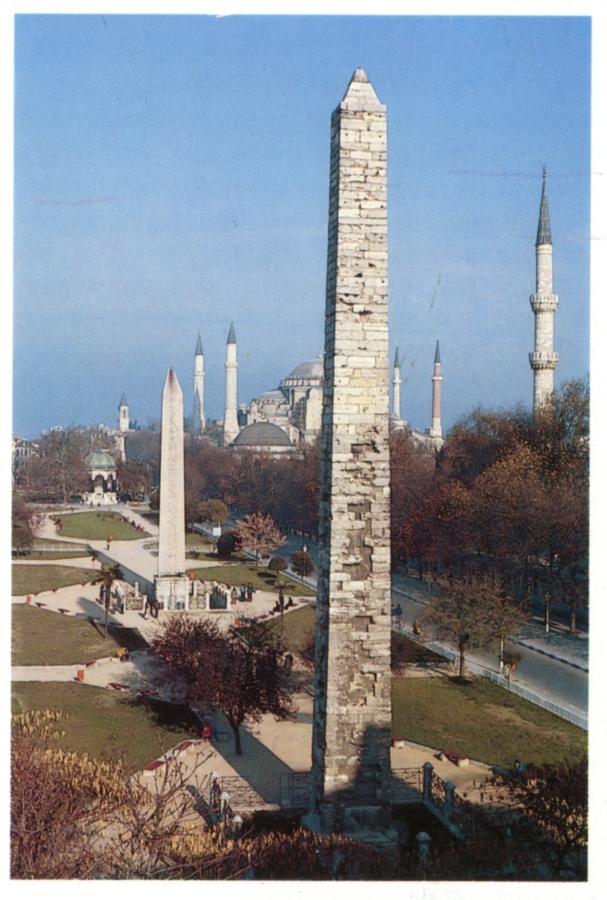

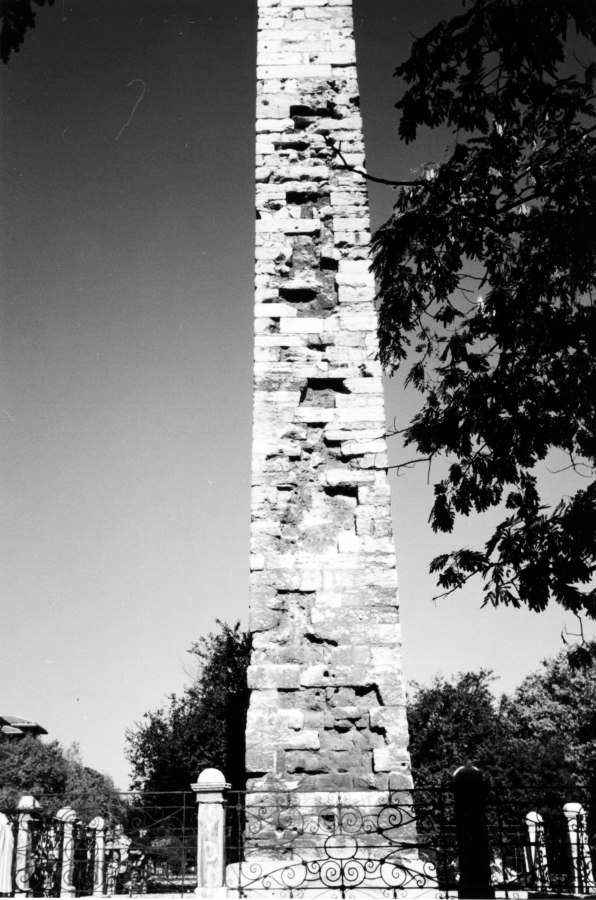

Coming back to the "ancient" Egyptian obelisks, we can now voice the idea that many of them were either cast of concrete or simply built of small blocks. The whole construction would then be covered by a layer of concrete or plaster. This is precisely how the famous 25-metre obelisk of Constantine was built - the one that stood at the Hippodrome of Czar-Grad, qv in fig. 19.65/66. It is presumed that the obelisk was erected by Constantine VII Porphyrogenetus in the alleged year 940 ([1464], page 48). The column was presumably "coated in gilded bronze plates with reliefs depicting the heroic deeds of the Emperor's uncle, Basil of Macedonia [the King of Macedonia, in other words - Auth.]" ([240], page 167). The concrete coating peeled off over the course of time, revealing the numerous small blocks of stone that the obelisk was built of, qv in fig. 19.67. A propos, the column was also known as the "Walled-Up Column or the Golden Column (Colossus)" ([240], page 166).