Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 19.

“Ancient” African Egypt as part of the Christian “Mongolian” Empire of the XIV-XVI century - its primary necropolis and chronicle repository.

11. The capital of Egypt was known as Babylonia in the XVI century. Ottoman crescents with a star and the Ottoman "bunchuks" of the Cossacks over the "ancient" Egypt.

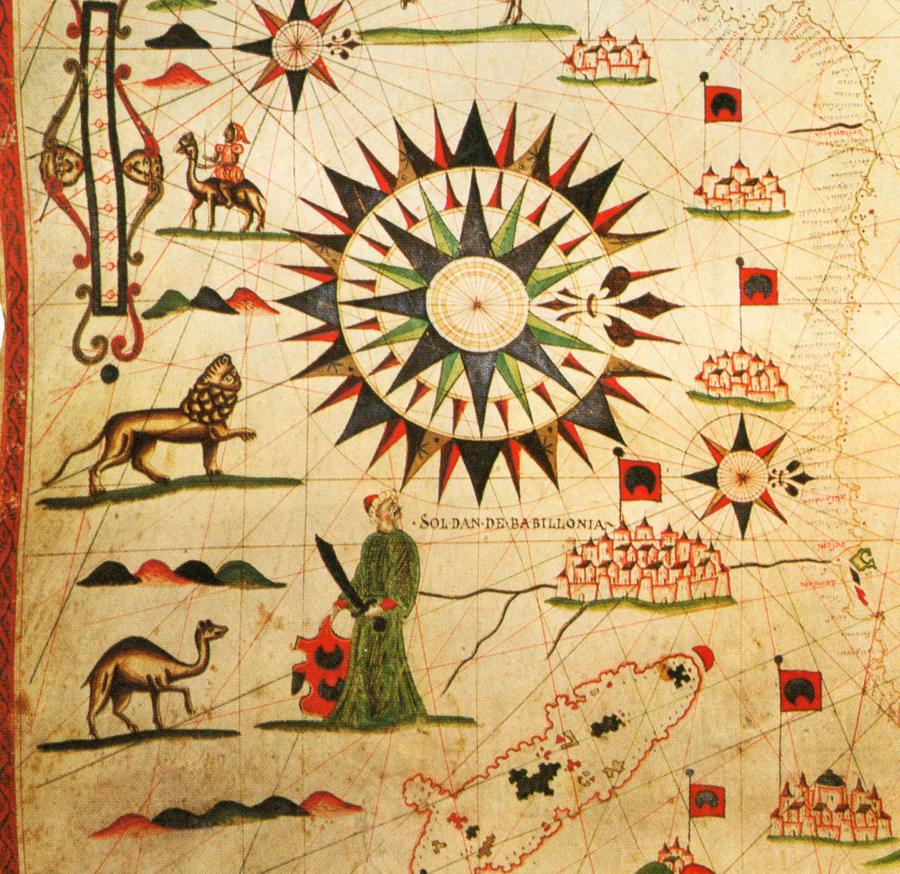

In the next volume, CHRON6, we shall demonstrate that the state of Egypt as described in the Bible can be identified as the mediaeval Russia, or the Horde. Apart from that, another name of Russia, or the Horde, was apparently Babylon, or Babylonia - most probably, a derivative of the term "White Russia". One may therefore expect to encounter the Imperial name "Babylon" in the "ancient" history of Egypt in Africa, since it was the primary royal graveyard of the great Czars, or Khans, of the Mongolian Empire, or a graveyard of the Babylonian (White) Horde, which had a special significance. Indeed, there are certain ancient maps where Egypt and its environs are referred to as "Babylonia". One of such maps, a rare portolano of 1599, is reproduced in fig. 19.107. Instead of "Cairo" we see the legend "Babylonia", and there is a banner with the Ottoman = Ataman crescent waving over the city (see fig. 19.108, and also [1058], page 109).

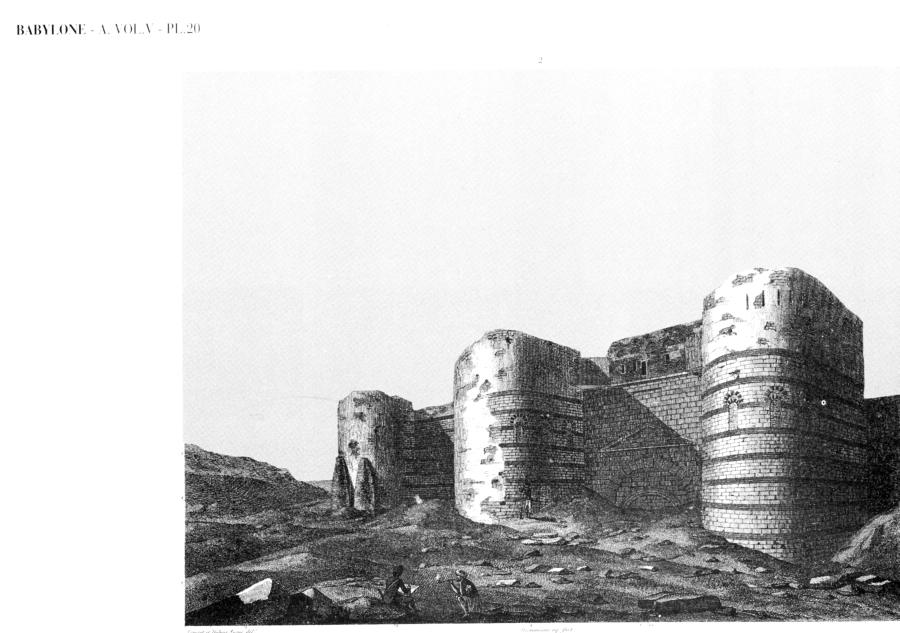

The remains of sturdy fortifications of the "ancient" Egyptian Babylon, near Cairo, are shown in fig. 19.109. The drawing was made by Napoleon's artists ([1100]). These constructions are most likely to date from the Ottoman epoch of the XV-XVI century.

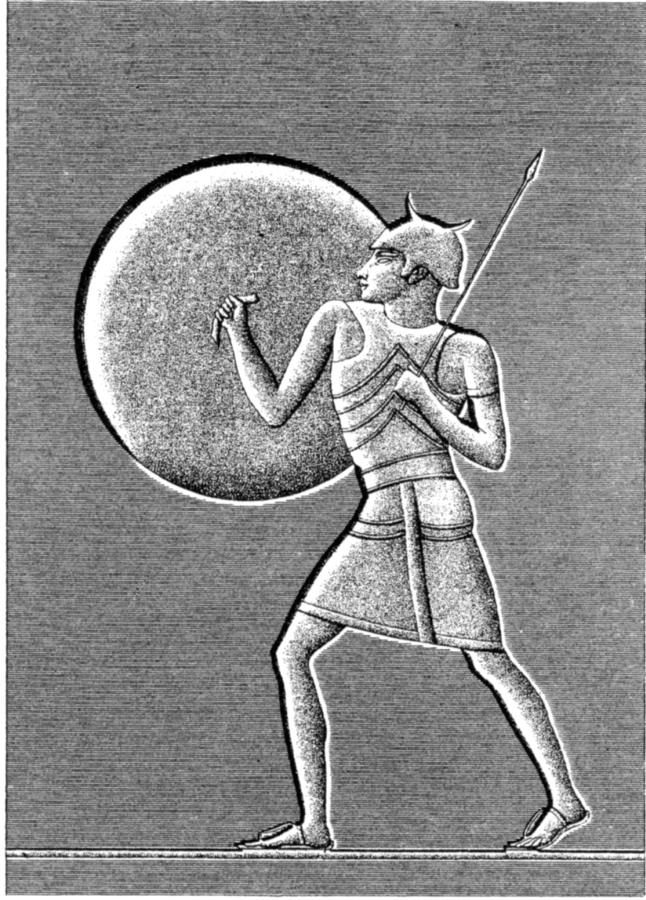

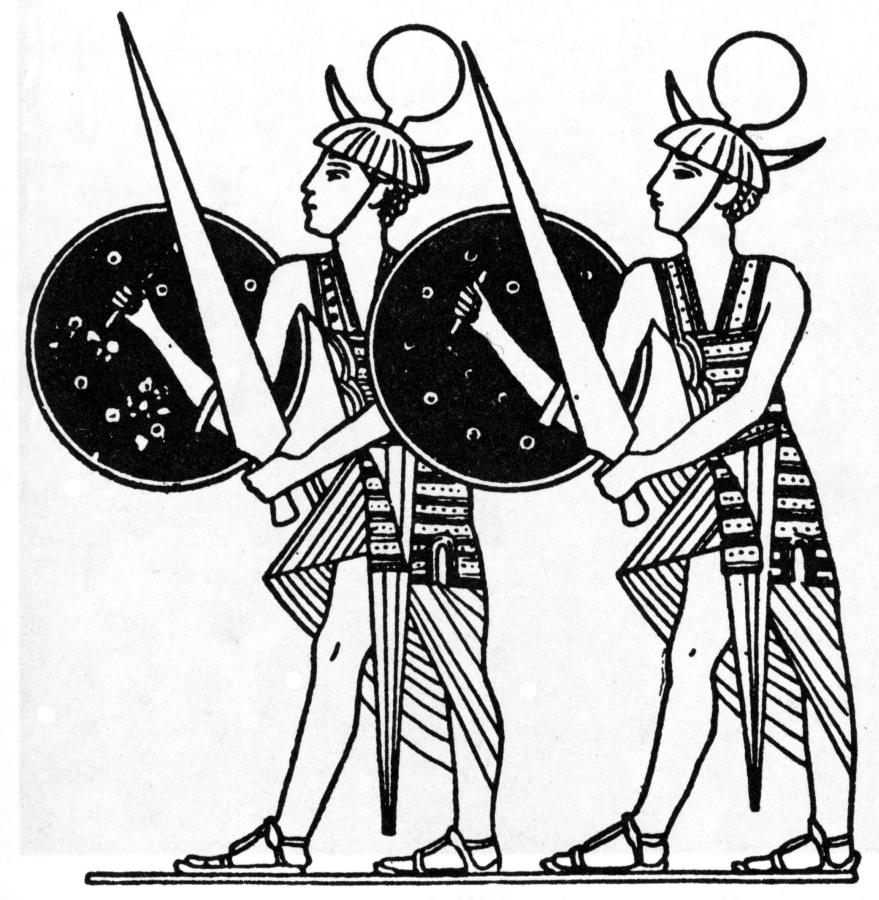

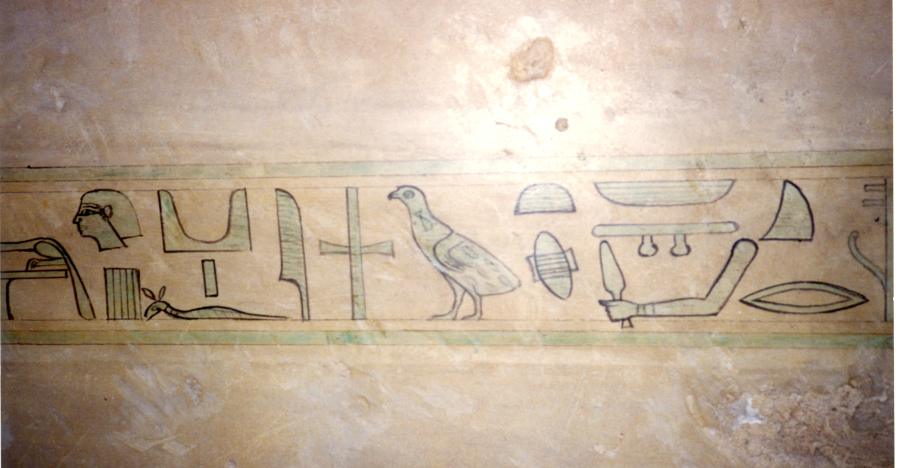

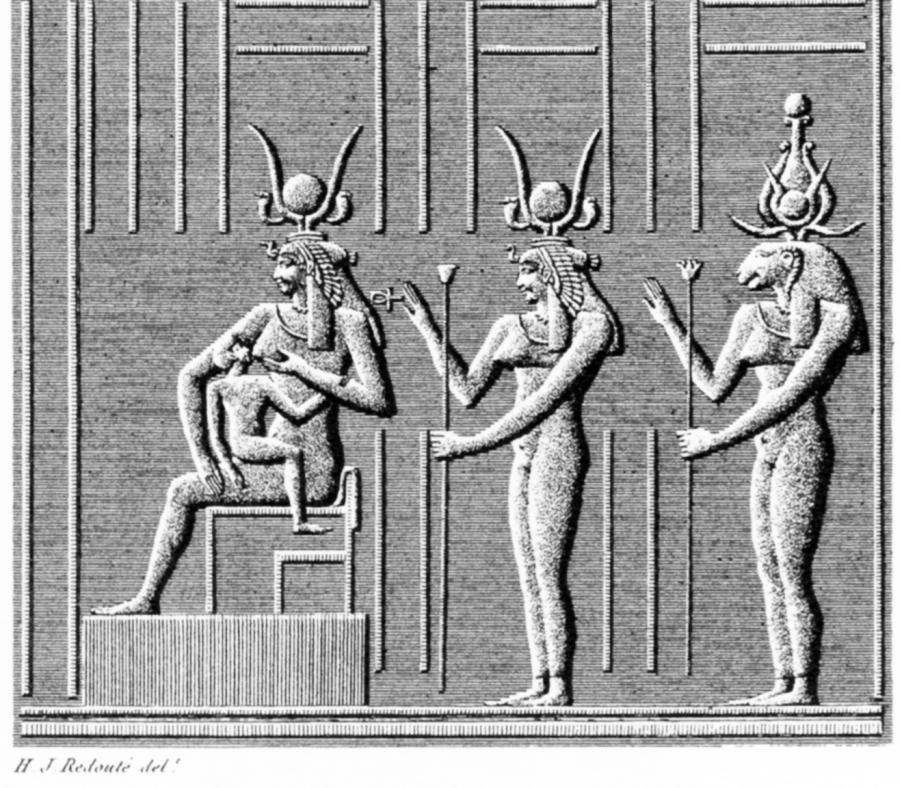

Incidentally, Ottoman crescents also adorned the helmets of the "ancient" warriors from the Egypt of the Pharaohs - see figs. 19.110 and 19.111, for instance.

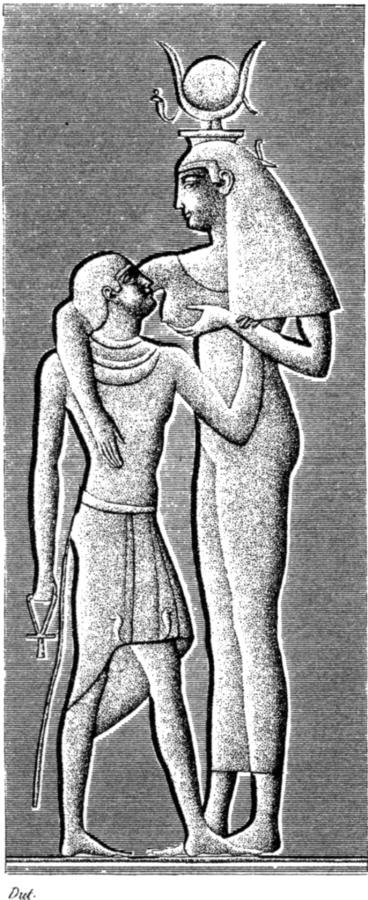

Furthermore, we see the Ottoman crescent crowning the heads of certain "ancient" Egyptian deities - see fig. 19.112, for instance.

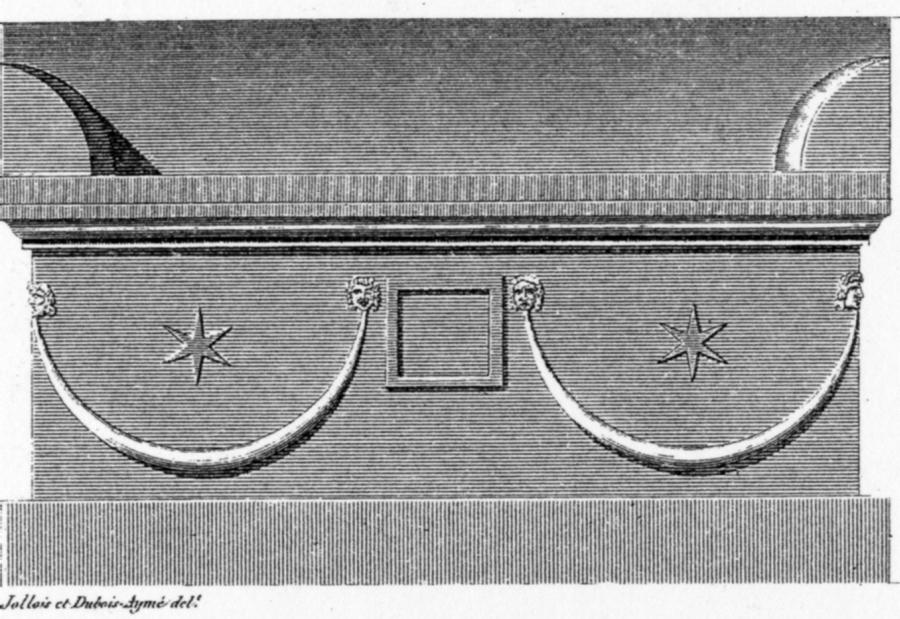

The Ottoman = Ataman crescent with a star had also adorned the walls of the "ancient" Egyptian temples. One of such drawings can be seen in fig. 19.113.

Above we have demonstrated that the famous "ancient" epoch of the Hiksos in the "ancient" Egypt is a duplicate of the Cossack = Ataman (Ottoman) dynasty of the XIV-XVI century, which was regnant in Egypt. Let us add another vivid detail to our reconstruction. The so-called "bunchuks" were a well-known military attribute of the Cossack troops of the Horde. According to the Encyclopaedic Dictionary, "a bunchuk (Turkic) is a long pole with a sphere and a keen edge on top, decorated with horsehair and trusses; served as a symbol of an Ataman's (or Getman's) authority in the Ukraine and in Poland" ([797], page 178).

As a matter of fact, the Encyclopaedic dictionary slyly omits some information. The Cossack bunchuks symbolised the authority of the Atamans far beyond the territories of Poland and the Ukraine. For instance, in fig. 19.114 we see the coat of arms of the Ural region, which was ratified in 1878. The old description of the coat of arms is as follows: "A green field . . . with golden . . . bunchuks, topped with similar crescents facing upwards and golden spearheads" ([162], page 200). Therefore, the Cossacks from the Ural (formerly Yaik) preserved the bunchuks and also the golden Ottoman = Ataman crescents in their coat of arms up until the end of the XIX century. One must assume that the pressure of Scaligerian and Millerian history made the people forget that the Ottoman = Ataman bunchuks and crescents symbolised the authority of the Russian Empire, or the Horde, in many lands that lay beyond the territory of modern Russia. There are many surviving examples of this fact.

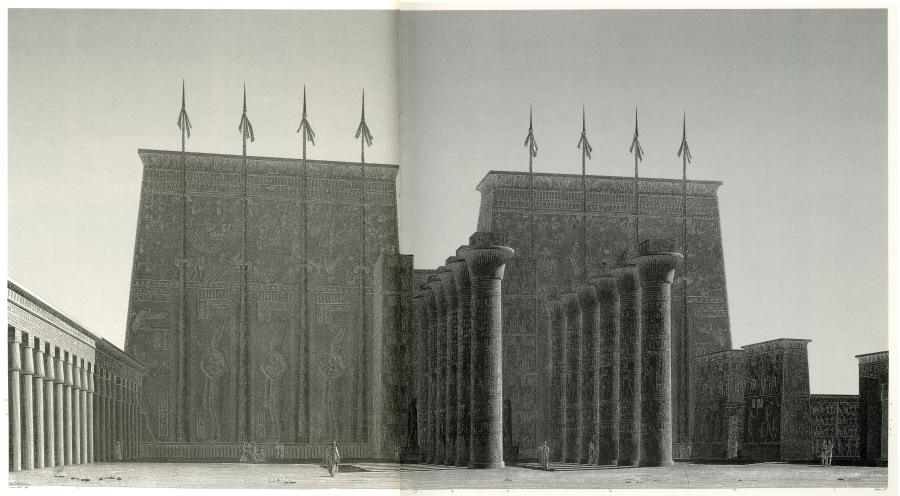

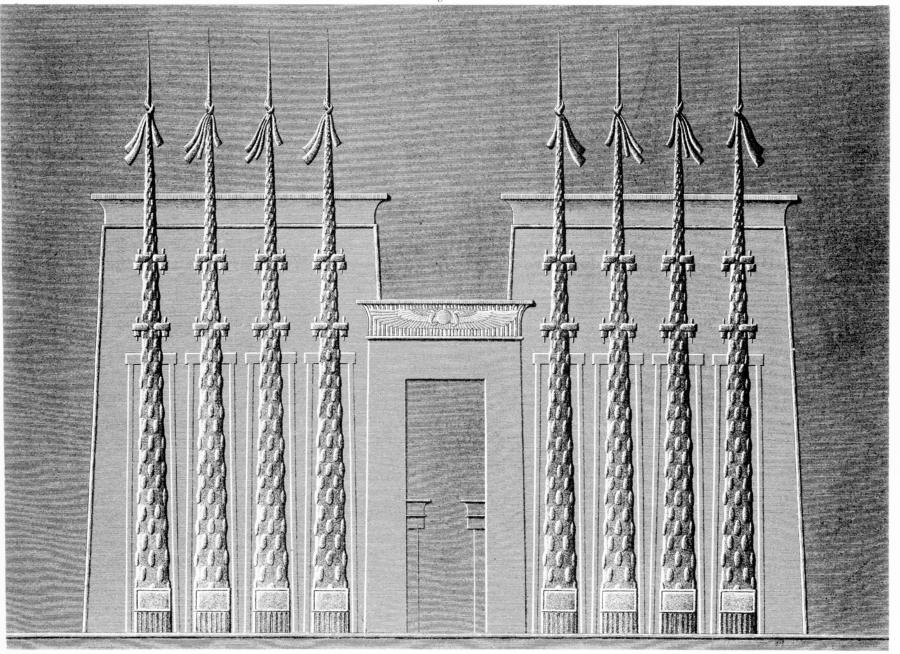

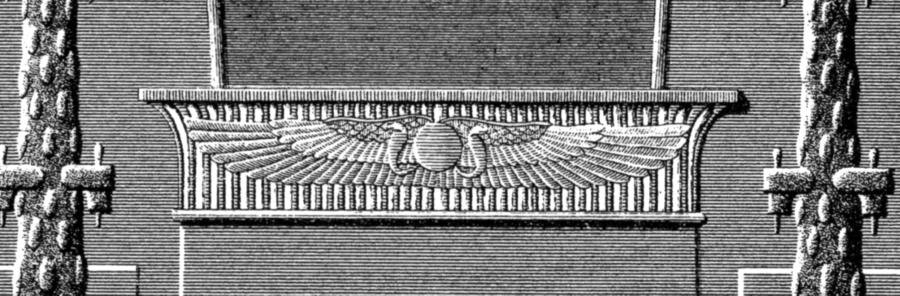

Indeed, let us turn to the history of the "ancient" Egypt, for instance. In fig. 19.115 we see the right half of the facade of an enormous temple in the "ancient" Egyptian city of Karnak. There are eight Cossack bunchuks over the temple - four on the left and four more on the right. The drawing was made by the artists of Napoleon when his troops invaded Egypt at the very end of the XVIII century ([1100]). It is perfectly clear that the bunchuks as used by the Horde and the Ottomans, which were topping the temples of the "ancient" Egypt, used to symbolise the power of the "Mongolian" Empire, which also included Egypt in the epoch of the XIV-XVI century. In fig. 19.116 we can also see tall bunchuks of the Cossacks and the Atamans near the southern entrance to the Great Karnak Temple ([1100]). One must note that there was another symbol of the Empire flowing over the temple entrance. Its heads look serpentine, facing left and right (fig. 19.117).

12. Napoleon's artists appear to have been afraid of reproducing the enormous Orthodox cross on the throne of the "ancient" Egyptian Colossus of Memnon in their accurate drawings.

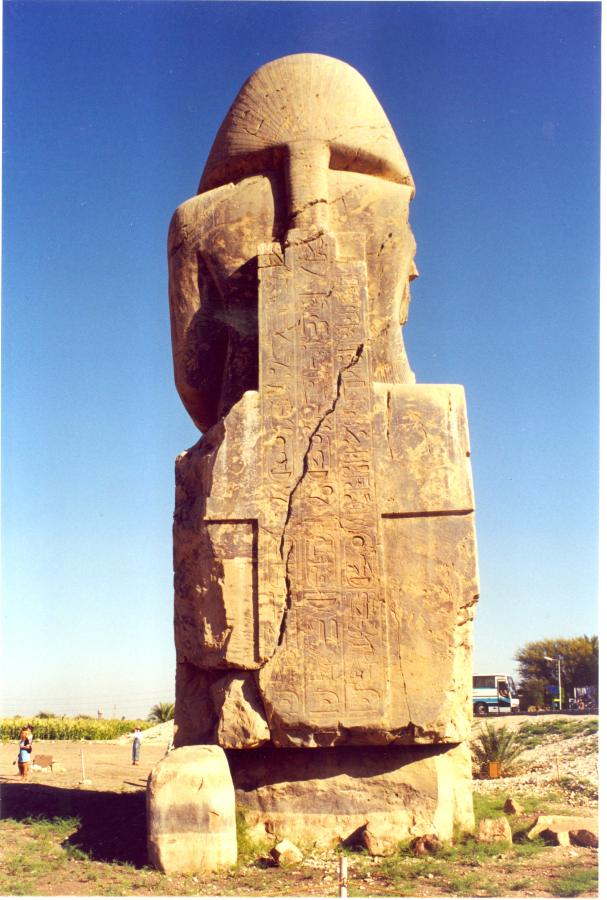

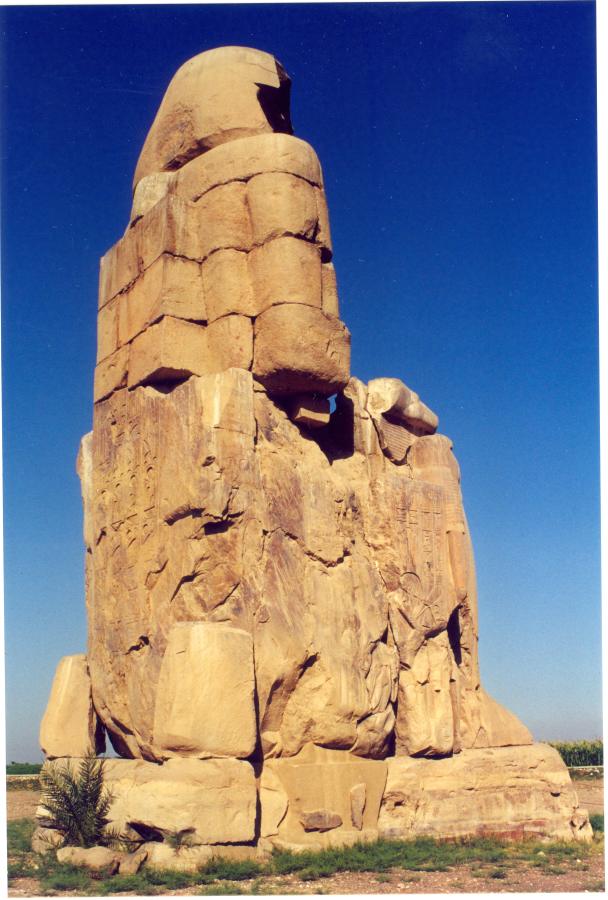

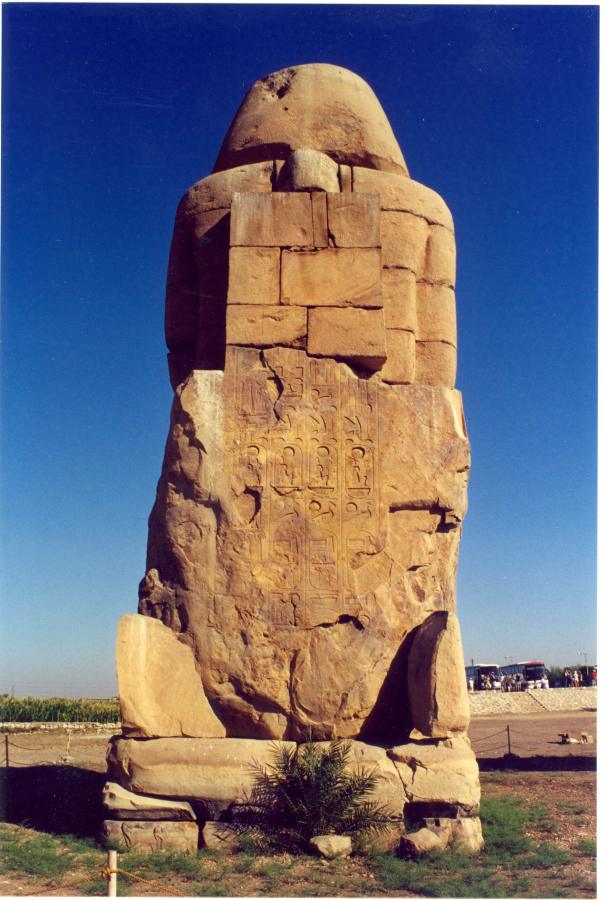

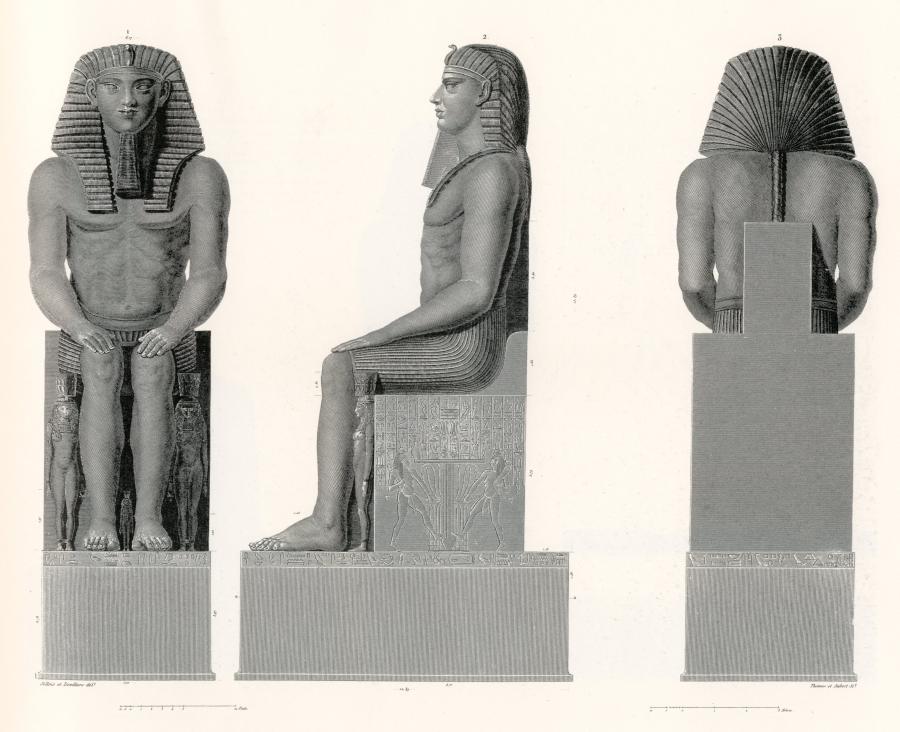

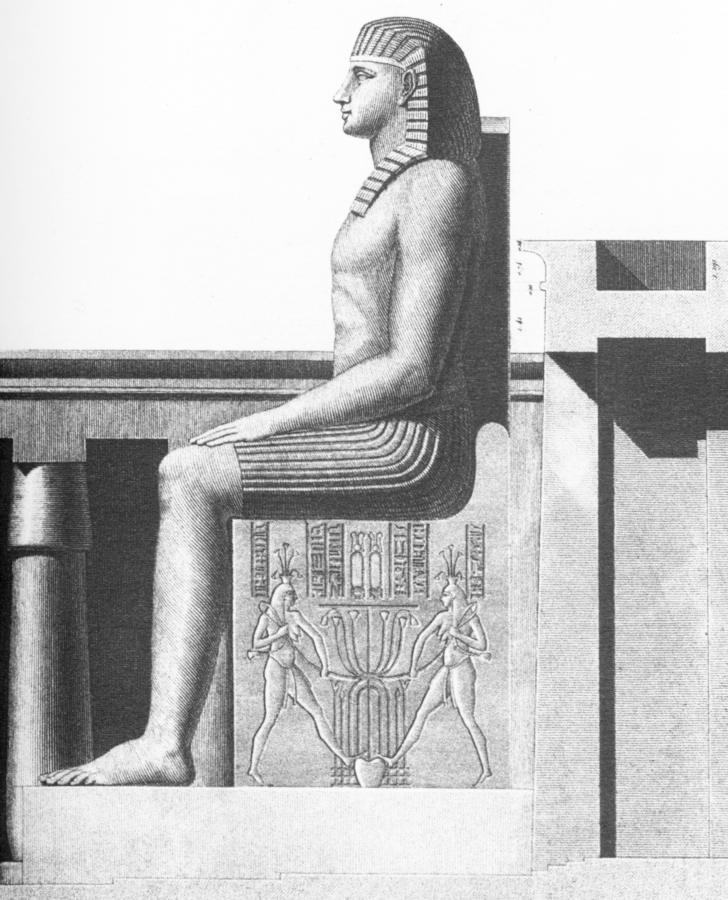

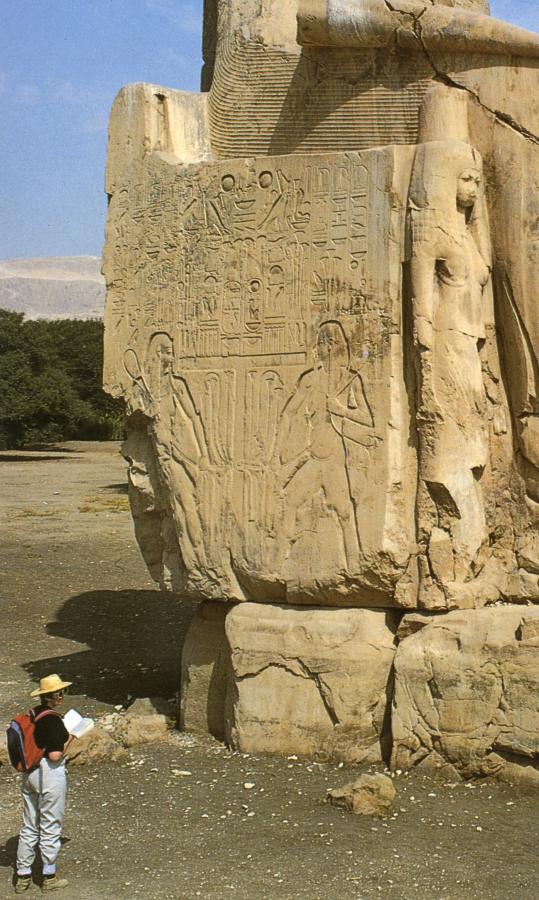

Above, in section 5 of the present chapter, we have told the reader that wide Orthodox crosses have survived on the backs of the thrones of both gigantic statues known as the Memnon Colossi today (see figs. 19.44, 19.118, 19.119, 19.45 and 19.46). The presence of the Orthodox cross here is explained perfectly well by our reconstruction, according to which the "ancient" Egypt of the Pharaohs was a Christian country in the epoch of the XIII-XVI century.

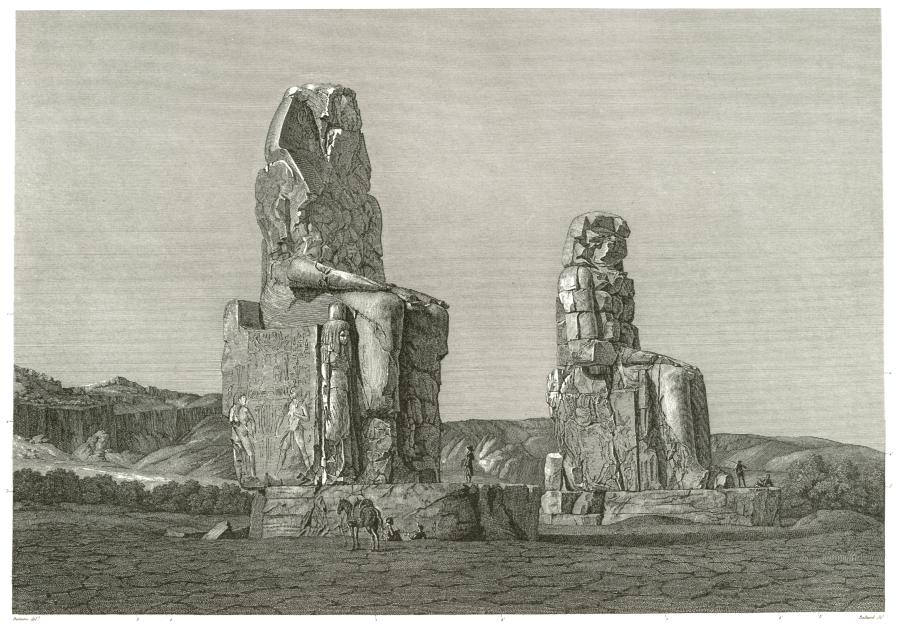

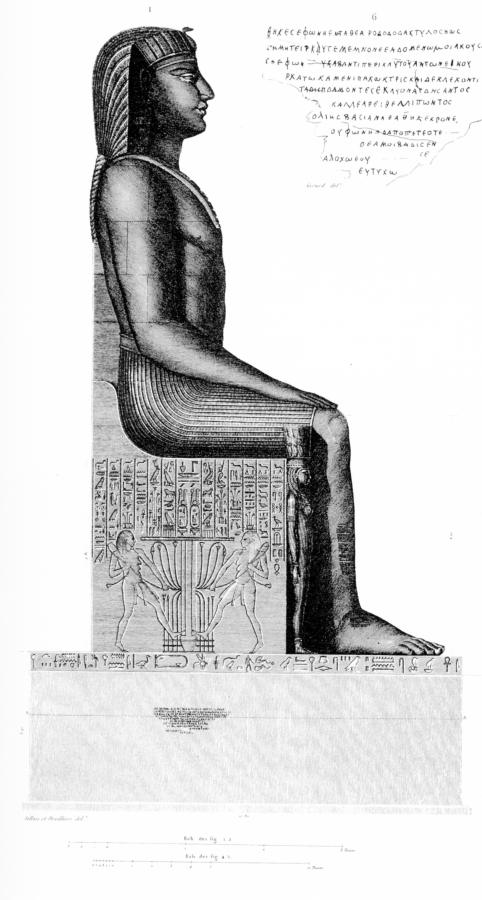

In fig. 19.120 we reproduce a drawing made by Napoleon's artists, which reproduces both of the Colossi with much precision ([1100]). As we can see in the photograph from a modern publication ([370]), the Orthodox Christian cross that has reached us in a better condition is on the back of the throne occupied by the southern figure, which is on the left of fig. 19.120. What do we see in the corresponding drawing made by Napoleon's artists? We must remember that they were very meticulous and earnest in their approach to the task of reproducing the Egyptian monuments as they were first seen by the Europeans, who came here in multitudes for the very first time at the very end of the XVIII century. All the drawings and copies collected in the fundamental edition ([1100]) are surprisingly accurate, up to the minor details. The French drawings are truly a priceless document that permits a glimpse of the authentic Egyptian history of the XVIII century - after all, many of the Egyptian monuments have perished since then ([370], [380], [728] and [2]).

Let us compare the French frontal drawing of the Memnon statues (fig. 19.120), which represents the front side of the statues, to their modern photograph reproduced in CHRON3 (fig. 17.8). The comparison demonstrates that there is no reason to doubt the accuracy of the French - they have copied every detail with the utmost meticulousness.

Now let us perform a similar comparison of the rear drawings of the southern Memnon statue as seen in the Napoleonic drawing (fig. 19.121) and the modern photograph (fig. 19.44). We see an amazing fact. The French artists were very accurate in their reproduction of the front and the sides of the statue; however, the rear part of the same statue wasn't reproduced completely. They simply omitted the Orthodox cross, leaving a blank spot as though they were afraid of something and tried to tell us that there was "nothing of interest here". It is significant that they did not fill the blank spot with any fantasy figures - the forgery was carried out very competently, as though they had simply lacked the time required to complete the drawing.

Therefore, it would be difficult to formally accuse the Napoleonic artists of premeditated forgery, although it is obvious to us that their hand wasn't stopped by a mere lack of time, but rather the circumstance that was revealed to them right there and shocked them deeply - the enormous wide Orthodox cross on the throne of an "ancient" Egyptian statue. It is perfectly obvious that this fact, which must have caught them by surprise, worried them greatly. It is possible that the French encountered many similar testimonies that the "ancient" Egypt of the Pharaohs had been a Christian country. Another example of an Orthodox cross on the back of an "ancient" Pharaoh's throne was reproduced in fig. 19.39.

All such facts radically contradicted Scaligerian history, which was already perceived as correct by Napoleon's artists as well as the archaeologists and historians that accompanied them. One must think that after some consideration they made the decision that must have been the only one possible for them - namely, to reproduce nothing that would contradict the version of the "ancient" history that they were accustomed to, and to include no details that could have provoked amazed enquiries into the albums and reports that they published. There may have been recommendations to chisel off such "heretical" artwork, best of all without any witnesses. Cannonballs were used for the objects located too far above the ground level, fired from point blank range for extra security. This was the case with the face and headdress of the Great Sphinx ([380], page 77). Kegs of gunpowder were used for constructions of tough basalt. In general, ancient history was in need of some amendments.

We are confronted by an important question in this regard. Are all the drawings made by the French artists of Napoleon available for researchers today? Did all of them get published? Apparently, the answer is in the negative. It seems as though a certain part of Egyptian monuments that were a menace to Scaligerian history, possibly a large part, was altogether omitted from the copies. Even if such "incorrect drawings" were made, they must have got buried in the depths of historical archives, away from the scientific community so as to raise no suspicions concerning the correctness of Scaligerian history.

We have witnessed it many times that it makes a lot of sense to compare different drawings of the same historical artefact made by different scientists and travellers in the XVII-XIX century. It would also be interesting to compare these pictures to modern photographs of the same object that represent its modern condition. We often discover significant changes in the condition of the monument that occurred over the last two or three hundred years. In some cases, we can clearly see the results of the tendentious Scaligerian editing performed in the XVII-XIX century.

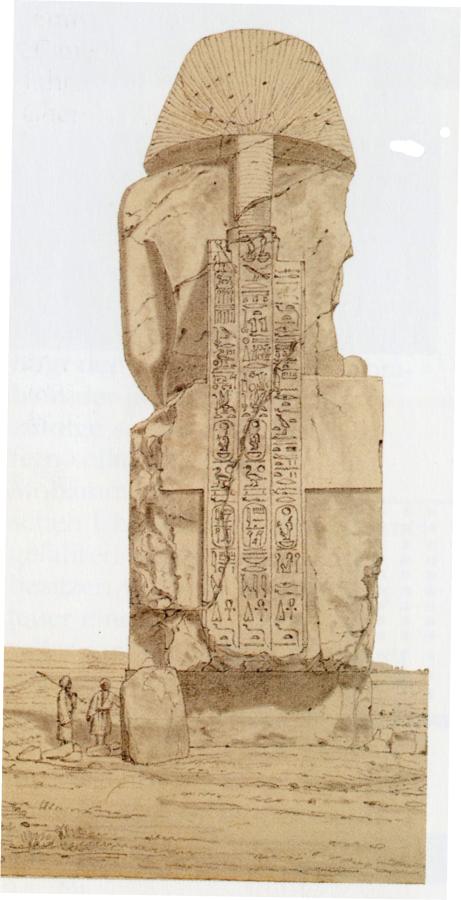

For example, let us consider the drawing of the Egyptian Colossus of Memnon as mentioned above, which was made in 1832 by the famous artist and traveller Frederick Catherwood (fig. 19.122). Unlike the French artists of Napoleon, Catherwood reproduced the wide Orthodox cross from the back of the throne very faithfully. Moreover, he was very accurate in his attempt to reproduce the hieroglyphic inscription that covered the entire vertical stripe of the cross. When we compare it to the modern photograph (fig. 19.44), we see that the text is virtually invisible today. It is possible that someone used a chisel for making the inscription illegible. It would be very interesting to use the old drawing of Catherwood in order to read it. As we have mentioned above, Napoleon's artists failed to reproduce the cross, let alone the lettering upon it.

Let us consider the modern photograph of the Memnon Colossus attentively once again (fig. 19.44) and compare it with the French drawing in fig. 19.121. Another noteworthy circumstance catches our attention. Fig. 19.121 makes it perfectly obvious that in Napoleon's epoch there was a long inscription at the bottom of the statue, covering all of its sides. There is nothing of the kind here today. The inscription has been chiselled off, as we can clearly see in fig. 19.44. Therefore, the methodical destruction of Egyptian monuments continued after Napoleon.

Another interesting fact is as follows. The hair of the southern Colossus is tied into a braid (fig. 19.121) - in the exact same fashion as was popular with the Russians who lived in Novgorod in the Middle Ages, men as well as women. We mentioned it in CHRON4, Chapter 14:16. Therefore, we see that the same mediaeval custom of wearing one's hair in a braid was common for the men and women of Russia, or the Horde, and the "ancient" Egypt. The Cossacks have preserved a similar custom for a longer time - leaving a long lock of hair on top of the head (the so-called "oseledets").

13. Napoleon's artists reproduced the Christian motif of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross in their drawings of the "ancient" Egyptian Colossi of Memnon.

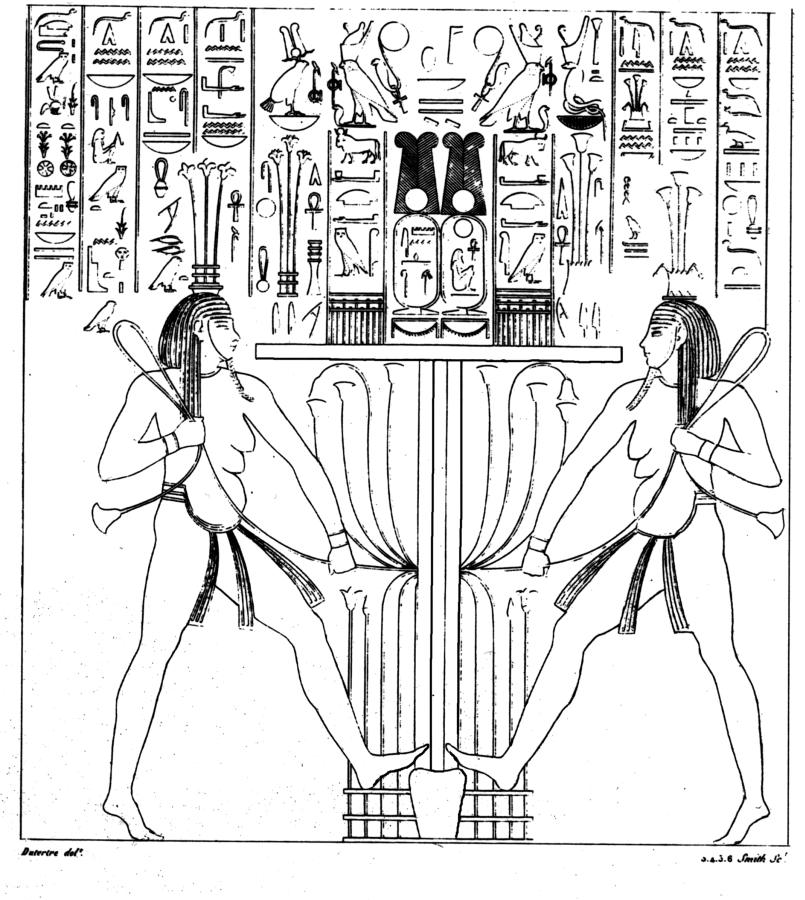

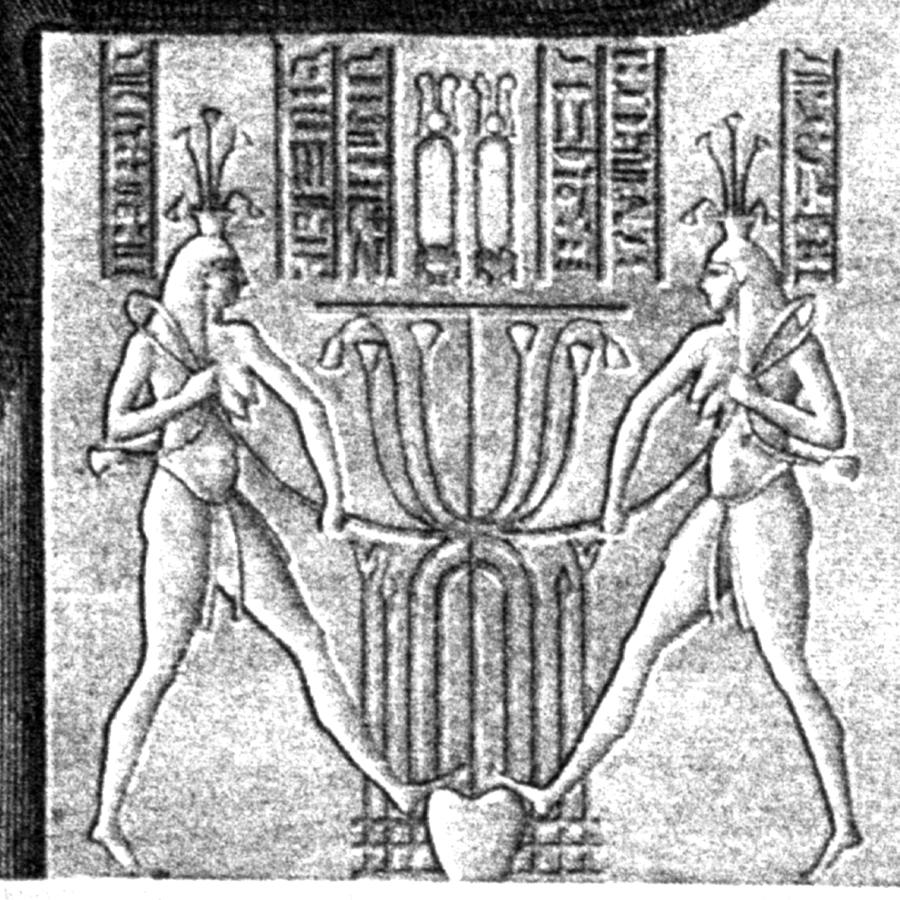

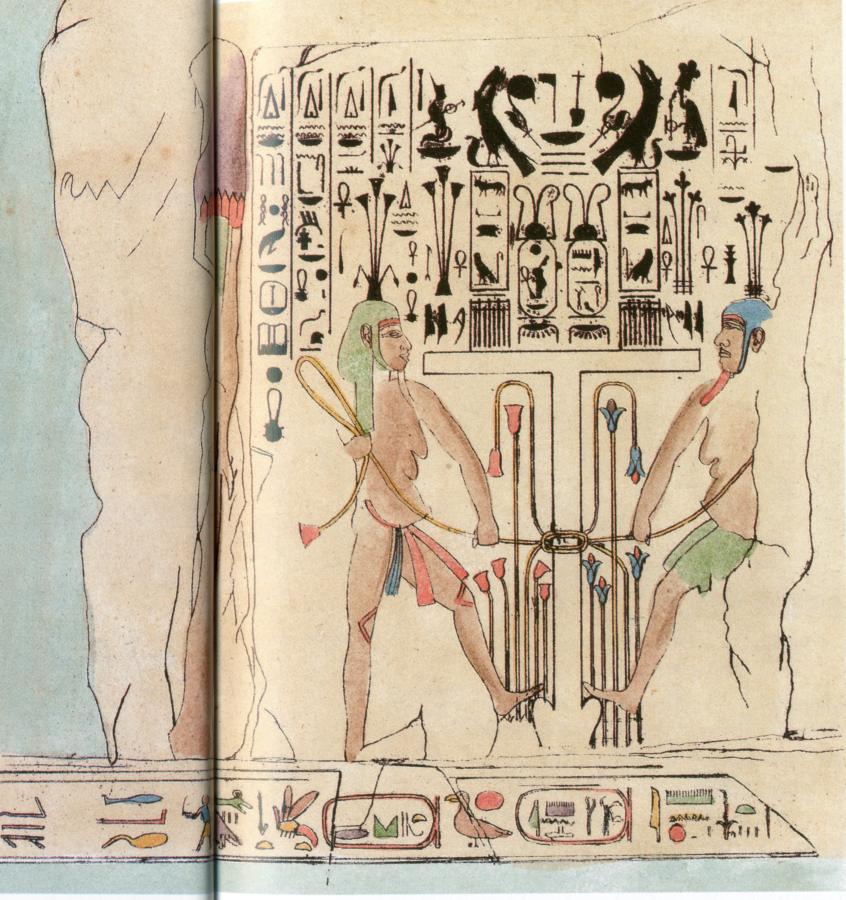

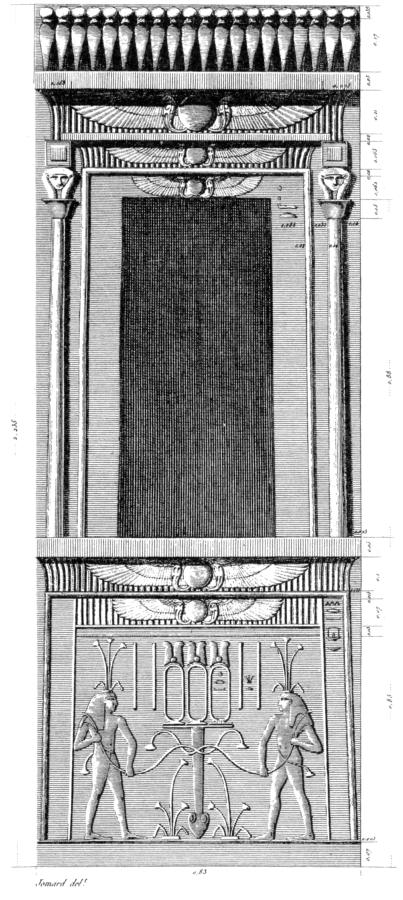

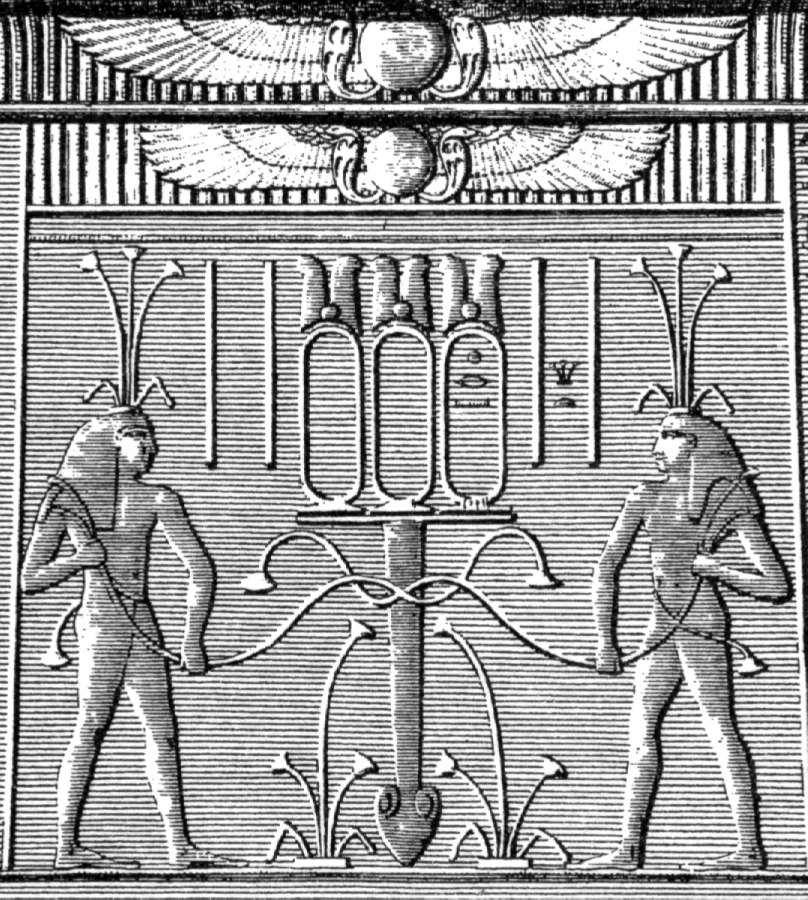

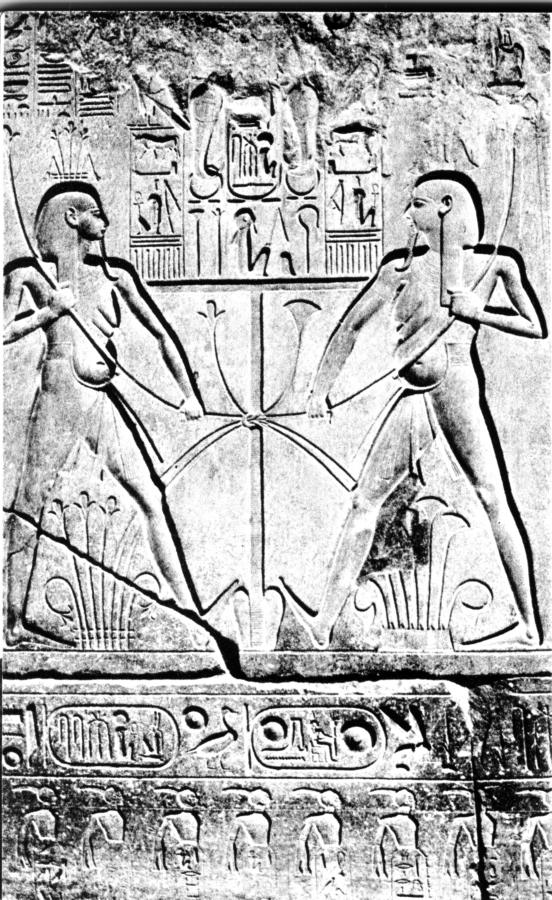

As we have witnessed above, the French artists explicitly failed to reproduce the enormous wide Orthodox cross that was present on the back of the throne occupied by one of the "ancient" Colossi of Memnon, qv above. On the other hand, there is a large piece of artwork on the side of the throne, which also appears to be Christian and mediaeval - namely, the famous Christian motif of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross (figs. 19.123, 19.124, 19.125 and 19.126). This "dangerous motif" must have escaped the recognition of the Napoleonic artists; in other words, they failed to identify it as Christian, and so they copied it meticulously. The "ancient" Egyptian bas-relief has fortunately reached our day and age; we reproduce its modern photographs in fig. 19.47 and in CHRON3, fig. 17.8.

In fig. 19.127 we reproduce the drawing of a side of the Colossus made in 1832 by Frederick Catherwood. In fig. 19.128 one sees a drawn copy of the actual motif in question from the side of the throne. Once again, it is expedient to compare the drawing of Catherwood (fig. 19.128), the drawing of Napoleon's artists (fig. 19.124) and the modern photograph (fig. 19.47).

It has to be said that the Exaltation of the Holy Cross must have been a popular enough motif in the "ancient" Egypt. Apart from the Colossi and the temples of Memnon, we can see it in a similar bas-relief from Phile, for instance (fig. 19.129). The T-shaped cross is very recognizable here (fig. 19.130). By the way, one must also note the three imperial "Mongolian" bicephalous eagles spreading their wings over the scene.

A different version of the same scene can be seen in a bas-relief from Luxor (fig. 19.131).

It is easy to understand why the French artists failed to pay attention to the Christian bas-reliefs of this sort that they encountered in Egypt. The matter is that the ancient T-shaped Christian cross that they depict isn't quite as popular and famous today as it was in the epoch of the XIII-XVI century. By the epoch of Napoleon, people have already forgotten this archaic shape of the Christian Cross, which was common in the XII-XVI century. If this wasn't the case, they would probably have used chisels for destroying the "ancient" Egyptian artwork that depicts it instead of reproducing such crosses in their drawings.

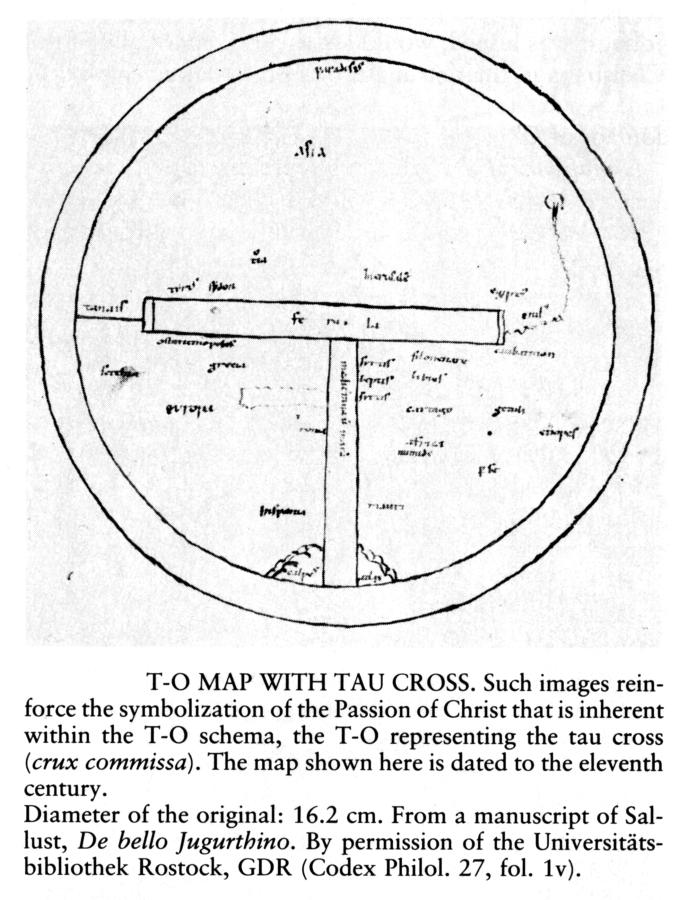

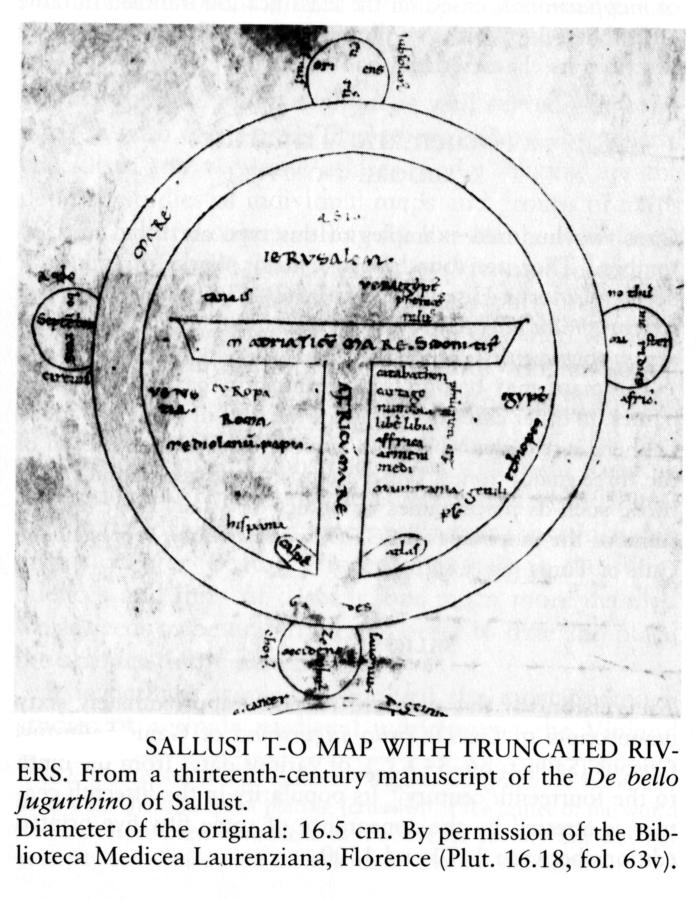

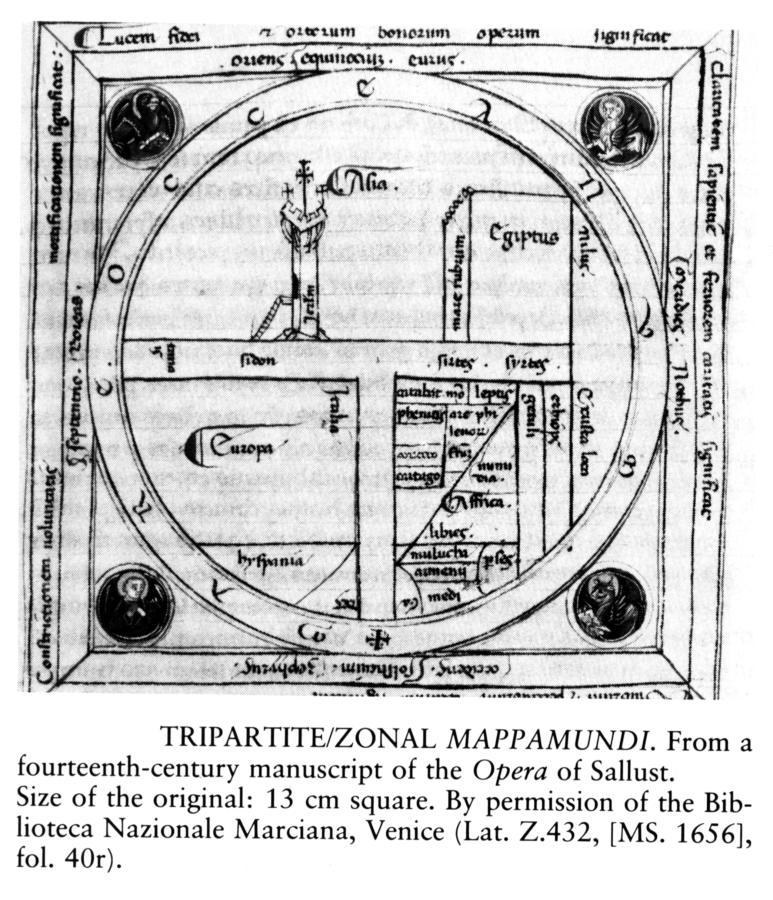

The fact that the "ancient" Egyptian bas-reliefs from the Memnon Colossi depict the Christian cross becomes obvious from a comparison with some of the ancient world maps, where the Christian cross that divides the world into three parts has the shape of the letter T; this is recognized by historians themselves. Examples of such maps can be seen in figs. 19.132, 19.133 and 19.134.

Two enormous Christian T-shaped crosses were depicted on the Russian veil of Helen of Volokh dating from 1498 (figs. 19.135 and 19.136). We see a church procession participated by the Russian Czar (or Khan of the Horde) Ivan III with his wife Sophia, son Vassily and grandson Dmitriy Ivanovich ([812], page 60).

14. The "ancient" Egyptian Osiris as Jesus Christ.

Let us consider the "ancient" Egyptian legends of Osiris - the god, the king and the human. We see obvious parallels with the Evangelical story of Jesus Christ. Historians write the following: "Egyptians claimed that their history began from the reign of Osiris . . . Osiris, the god, the king and the human being, is recollected as a monarch of limitless kindness and wisdom, who had united all the nomadic tribes and taught them to turn the harm inflicted by the floods to their advantage, to use irrigation to fend off the onslaught of the desert, and particularly to grow wheat for making flour and bread, grapes for making wine and barley for the beer. Osiris also gave the nomads knowledge of metallurgy and taught them literacy and fine arts together with Thoth the Wise.

Having completed his mission, Osiris left his best friend and ally Isis, who was also his wife, to reign in his absence, and headed Eastward, to Mesopotamia, in order to teach all the other nations. Upon his return, Seth, the brother of Osiris, lured the latter into a trap, killed him and usurped the throne, having strewn the parts of his brother's body all across Egypt. The grief-stricken Isis set forth to search for her beloved husband, and, divinely-inspired, put the parts of his body together with the aid of the loyal Anubis. And a miracle occurred: owing to the tears cried by his grieving wife Osiris resurrected and ascended into the heavens, leaving her in the company of their son Horus. Horus grew up, and, growing stronger in the course of a long struggle, finally defeated the usurper, becoming the successor of his father" ([370], page 5).

This legend is most likely to be based on the Christian Evangelical story of Jesus Christ. The name Osiris may stand for "Cyr-Is", or "Czar Jesus". On the other hand, it can also be interpreted as "Assyrian". As we have discovered, Assyria as described in the Bible identifies as Russia, or the Horde. Therefore, the Egyptian myth of Osiris appears to have preserved memories of this period in the history of African Egypt, when it was conquered by the Christian army of Russia, or the Horde. The conquerors taught the local populace a number of arts and crafts, as well as horticulture.

The name Isis must also be related to that of Jesus Christ.

Seth, the killer of Osiris, obviously identifies as Satan - a famous Christian image of the eternal foe of Jesus Christ.

The resurrection and ascension of Osiris correspond to the resurrection and ascension of Jesus Christ (1152-1185).

15. The "ancient" Egyptian goddess Isis and her son Horus are most probably Mary the Holy Mother of God and her son Jesus Christ.

Some of the "ancient" Egyptian Christian artwork did nonetheless end up on the pages of Scaligerian history textbooks, either by escaping the attention of the editors or a priori interpreted as "pagan", which made them harmless for the Scaligerian version - for instance, the numerous "ancient" Egyptian representations of Our Lady with the infant Christ. Two of such explicitly Christian bas-reliefs dating from the epoch of the "ancient" Egypt can be seen in figs. 19.137 and 19.138. In fig. 19.137 Isis, or Mary, is being offered the Christian cross. In fig. 19.138 the cross is held by Horus, or Christ.

In fig. 19.139 we see an "ancient" Egyptian bronze statue that portrays Isis with the infant Horus. A similar image is reflected in the "ancient" Egyptian stone sculpture dating from the alleged I century A. D. - "Isis feeding Horus" (see fig. 19.140). On the head of Isis we see a crescent with a star, or the sun - a symbol of Czar-Grad, in other words.

Scaligerite historians decided to treat all such cases in the following manner. They started to claim that all the artwork of this sort portrays the "ancient" goddess Isis and her son Horus rather than Mary and Jesus Christ, deities that were allegedly worshipped by the "ancient" Egyptians long before Christ ([533], Volume 1, pages 568-570). Historians tell us that "subsequently the motif of a woman feeding an infant shall be used in Christian iconography" ([930], page 36).

However, this "explanation" is most likely to be erroneous, and owes its existence to nothing but the fallacious Scaligerian chronology. The reverse scenario is closer to the truth. The name of the "ancient" Egyptian god Horus is also similar to "CHRISTOS", who was also referred to as Horus, as it turns out ([1207], page 23). The "ancient" Egyptian god Osiris is another reflection of Jesus Christ in the cult of the Egyptian Pharaohs.

16. The two famous boats of the "ancient" Egyptian Pharaoh Cheops (Khufu) were made of wooden boards. Therefore, they are of a very late origin, and their manufacture must have employed iron or steel saws.

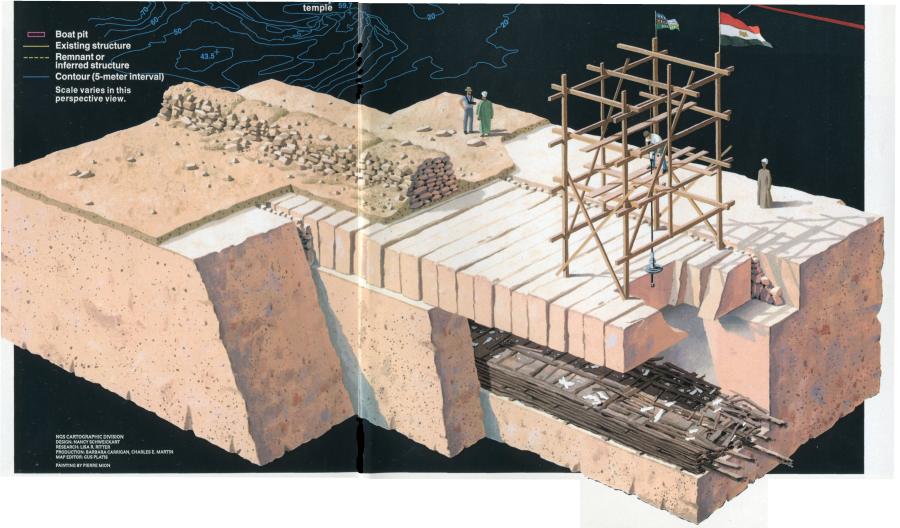

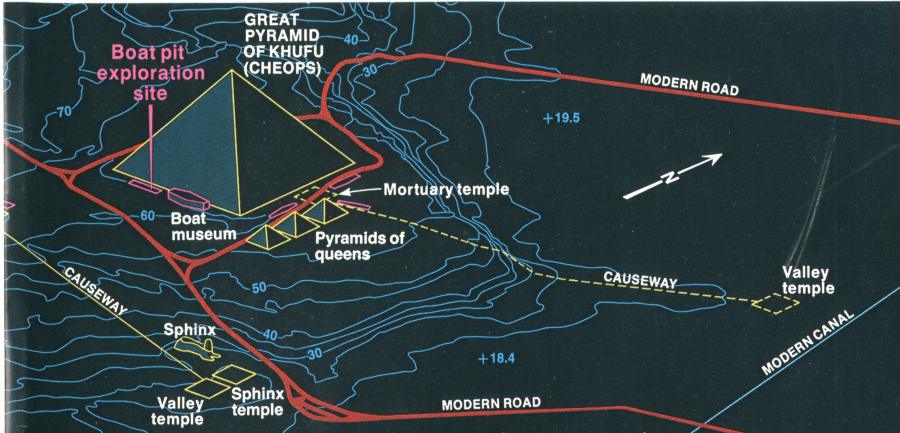

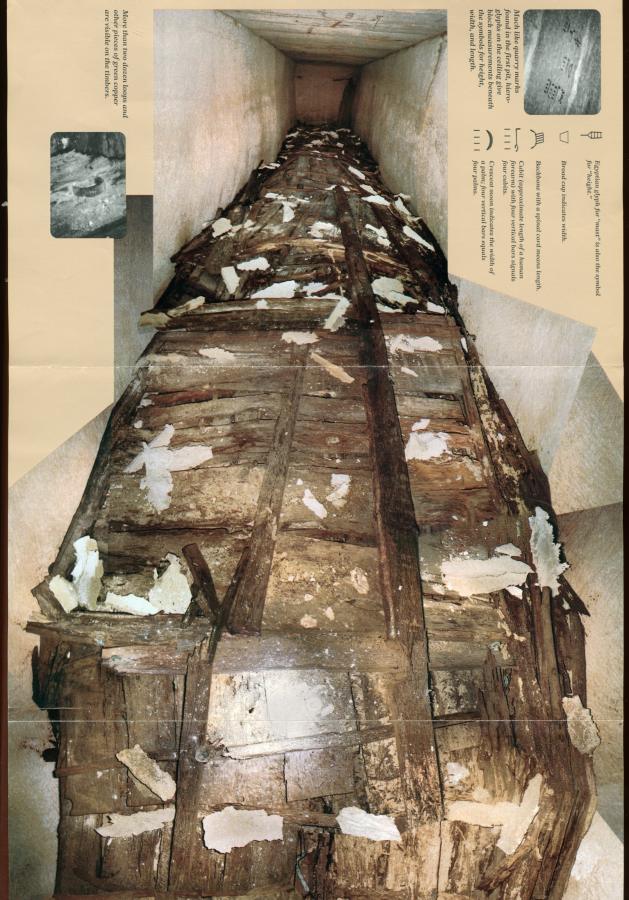

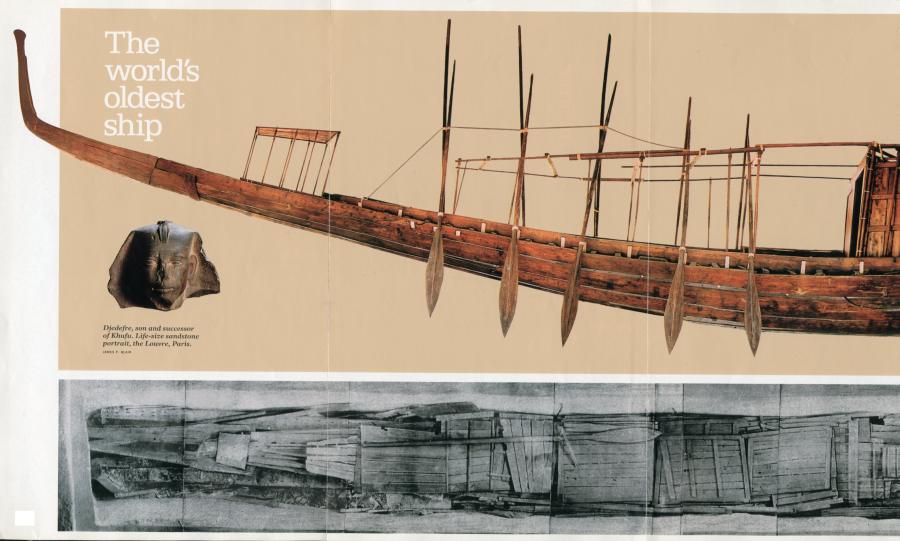

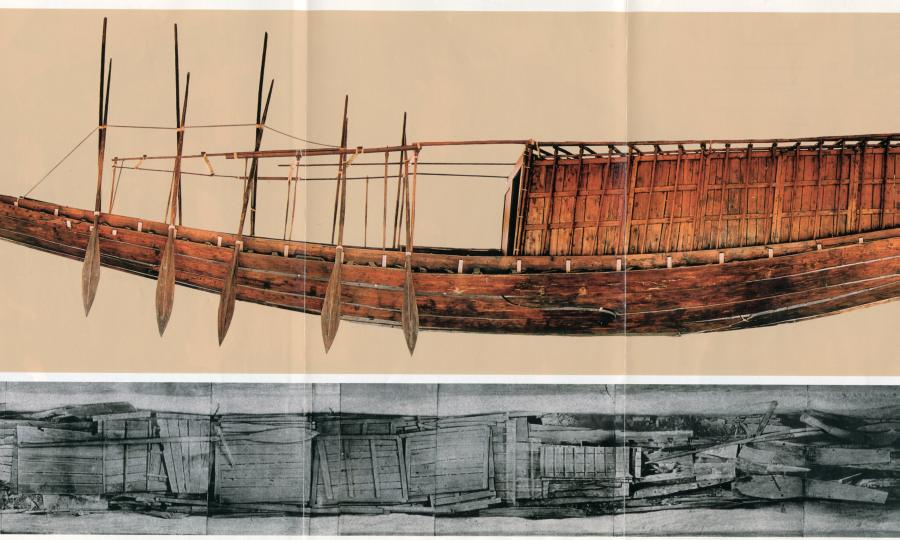

The fact that we shall be referring to in the present section was pointed out to us by I. V. Davidenko, Doctor of Geology and Mineralogy (Moscow). In 1954 a subterraneous chamber was discovered next to the largest European pyramid - the Pyramid of Cheops. It concealed a large wooden boat of the Pharaohs ([1281], page 513). The "ancient" Egyptians carefully disassembled it into individual details, which were then accurately piled up in the chamber. The chamber was opened by the researchers in 1954. They instantly noticed a fact that astonished them: "The chamber was sealed by the ancients with such care that it has preserved the aroma of cedar timber" ([1281], page 514). The boat was made of cedar. The first boat was taken apart into 1124 details, which were unearthed and accurately put together as a reconstruction of the boat. It has been put up for exhibition in a special museum built next to the pyramid of Cheops.

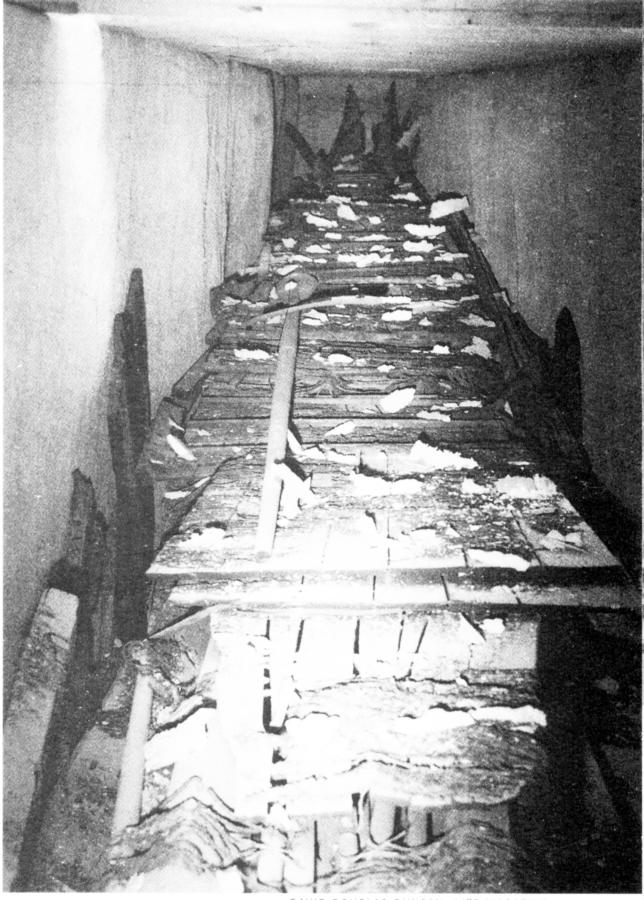

Already in 1954 scientists have noticed signs that indicated the presence of another subterraneous chamber nearby. Their assumptions were soon proven right - a second chamber was found next to the first, containing another Pharaoh's boat, also disassembled. Researchers treated this boat differently - they didn't touch it, drilling an accurate hole in the wall of the chamber, which was used for filming. The chamber was then re-sealed with great care. The second boat was left in the chamber just as it was discovered ([1281], page 513).

The site of the finding is indicated in fig. 19.141, which we took from [1281], page 520. Fig. 19.142 represents a section view of the subterraneous chamber that conceals the boat. Egyptologists and archaeologists date both royal boats to the epoch of the "ancient" Egyptian Pharaoh Khufu, or Cheops ([1281], page 522). They are considered to be funereal boats, and their age is said to equal 4600 years ([1281], page 514). The first one was used for the transportation of the body of Pharaoh Cheops ([1281], page 520). The second boat accompanied the first. The length of the first boat equals 142 feet, or 43 metres; the second boat is of a similar size.

Let us enquire about the following. How can it be that the aroma of cedar timber, which was noticed by the discoverers of the chamber, hasn't evaporated in 4600 years? See [1281], page 514. This is highly dubious. Maybe the boats are not as ancient as Scaligerite historians claim them to be, after all.

Another question that arises in this respect is as follows. Modern historians are trying to convince us that the Pharaohs lived right next to the pyramids. In this case, why would one have to build two enormous boats whose length exceeds forty metres in order to transport the Pharaoh's body over the small distance that lay between the palace and the pyramid? It is suggested that a symbolic voyage across the Nile was the only reason. This may be so.

On the other hand, our reconstruction suggests a different explanation, which appears more natural to us. Apparently, the "Egyptian Pharaohs" were the Czars, or Khans, of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire, whose residence was at a considerable distance from Africa and the country known as Egypt today - in Russia, or the Horde, that is, or the Ottoman (Ataman) Empire. They were embalmed posthumously and embarked on a long voyage on seafaring vessels. This fact appears to have become reflected in the "ancient" Greek myth of Charon, the ferrymen of the dead who took them to Hades across the Styx. The embalming procedure was necessary for the preservation of the bodies during the long journey across the sea.

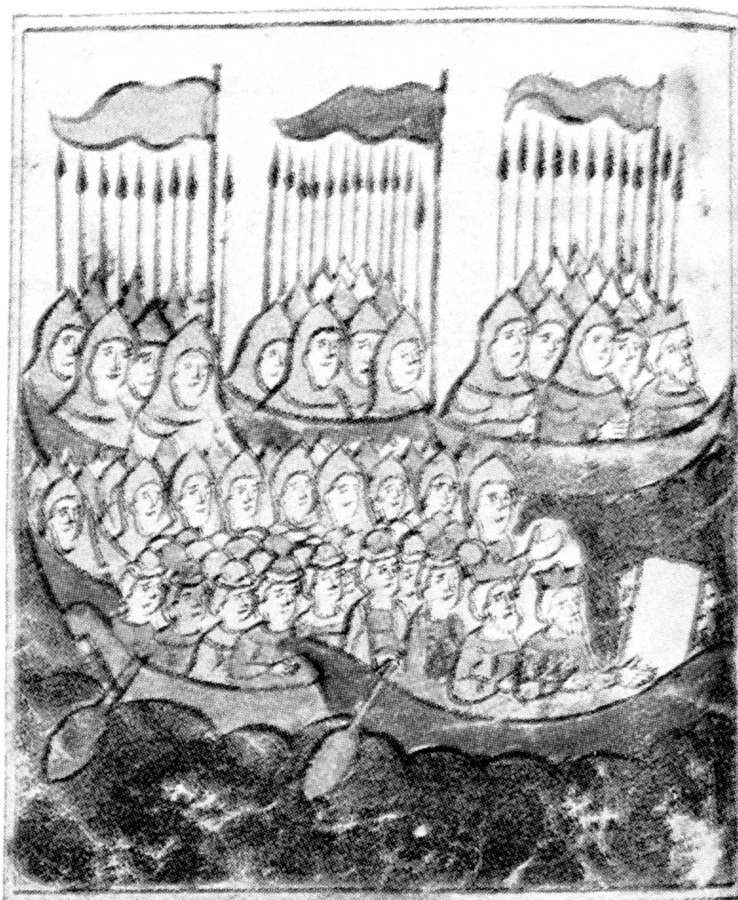

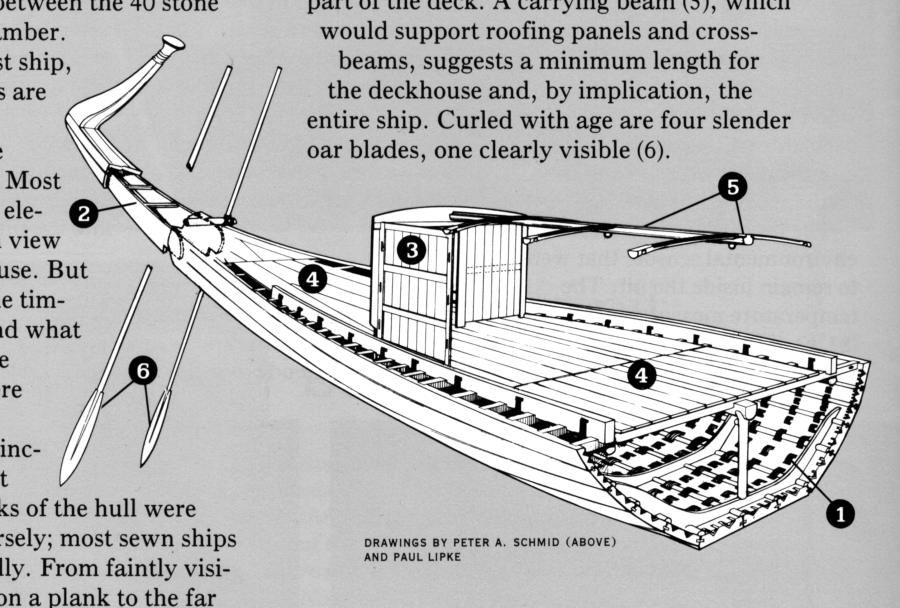

This reconstruction instantly puts things into a perspective. The bodies of the deceased Czars, or Khans, were taken from Europe to Africa on large rowboats, which could navigate rivers as well as the coasts of seas; such maritime voyages are known to us well enough from Russian history. The Russians used rowboats to reach Constantinople. Cossack rowboats still navigated the seas in the XVII century. Such boats have no need for a keel, due to the absence of sails. The longer the boat, the greater its ability to withstand sea waves. This may explain the large size of the boats of the Pharaohs - close to 40 metres.

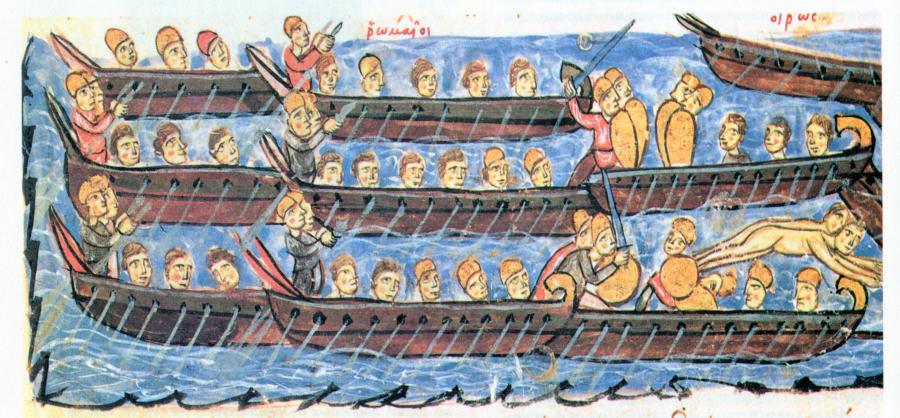

We must point out that the drawings of the old Russian rowboats are very similar to the boats of the Pharaohs. The same characteristic shapes and the same tall head and stern with curved ends. Russian rowboats are crescent-shaped, likewise the boats of the pharaohs. Russian rowboats can be seen in figs. 19.143, 19.144 and 19.145. In figs. 19.145 and 19.146 we see old drawings of Byzantine rowboats, which seem to be just the same as their Russian counterparts in shape and construction.

Thus, the "Mongolian" funereal rowboats would bring the body of the deceased Great Czar, or Khan, to the port of Alexandria in the estuary of the Nile, and then go up the Nile, reaching Cairo with its royal graveyard of the Gizeh. The boats would then be buried alongside the pharaoh. Therefore, we are of the opinion that the pair of boats as found in the subterraneous chambers was used for the transportation of the Pharaoh's body and ritual paraphernalia from Europe to Egypt.

We must emphasise that both boats were made of cedar ([1281], page 514). However, no cedars fit for timber have ever grown in Egypt. Hence the assumption of the historians that cedar timber was brought to Egypt from Lebanon ([1281], page 514). It has to be said that cedar trees also grow in Europe and in Siberia in large quantities.

In figs. 19.147 and 19.148 we see photographs of the two subterraneous chambers where the disassembled rowboats of the Pharaoh were discovered. Fig. 19.147 shows the first boat, and fig. 19.148, the second.

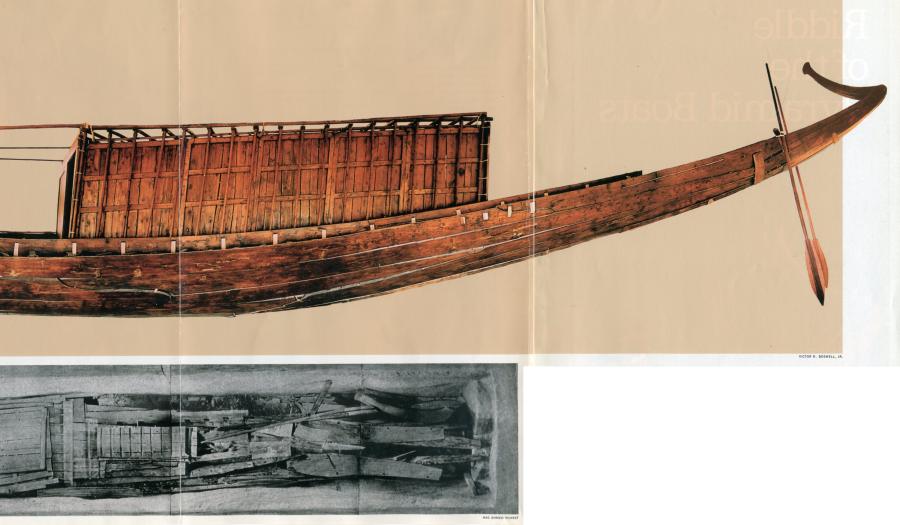

Figs. 19.149, 19.150 and 19.151 show the first of the pharaoh's boat in the assembled state. The drawings below correspond to the initial locations of the boat's parts in the subterraneous chamber. Fig. 19.152 represents the modern scheme of the boat, which was made during the assembly.

The important fact is that the Pharaoh's boats were made of wooden boards. This is visible in each of the photographs. Figs. 19.149, 19.150 and 19.151 also make it obvious that the edges of all the long boards are very smooth. The boards of the decks and the wooden shedding on top of the boat fit together perfectly well, without any gaps. Moreover, the hull boards are bent and also fit together perfectly; the technology of bending straight boards is also far from simple and tells us about the great skill of the "ancient" shipbuilders.

Our main conclusion is as follows. The "ancient" builders of the Pharaoh's rowboats must have used saws - it is very difficult to make such boards in such a quantity with nothing but axes. The saws had to be made of iron or steel. Therefore, the rowboats must date from the epoch of the XIV-XVII century - the 1600 years of their alleged age are right out of the question. Yet we are told that the "ancient" Egyptians who lived in the epoch of the Pharaohs were still unfamiliar with the metallurgy of iron, let alone steel saws. Therefore, the iron artefacts occasionally found in the tombs of the Pharaohs are usually declared rare and unique, or "later artefacts" that accidentally ended up in the royal tombs in later epochs.

17. Slavic ornaments on the "ancient" Egyptian clothing.

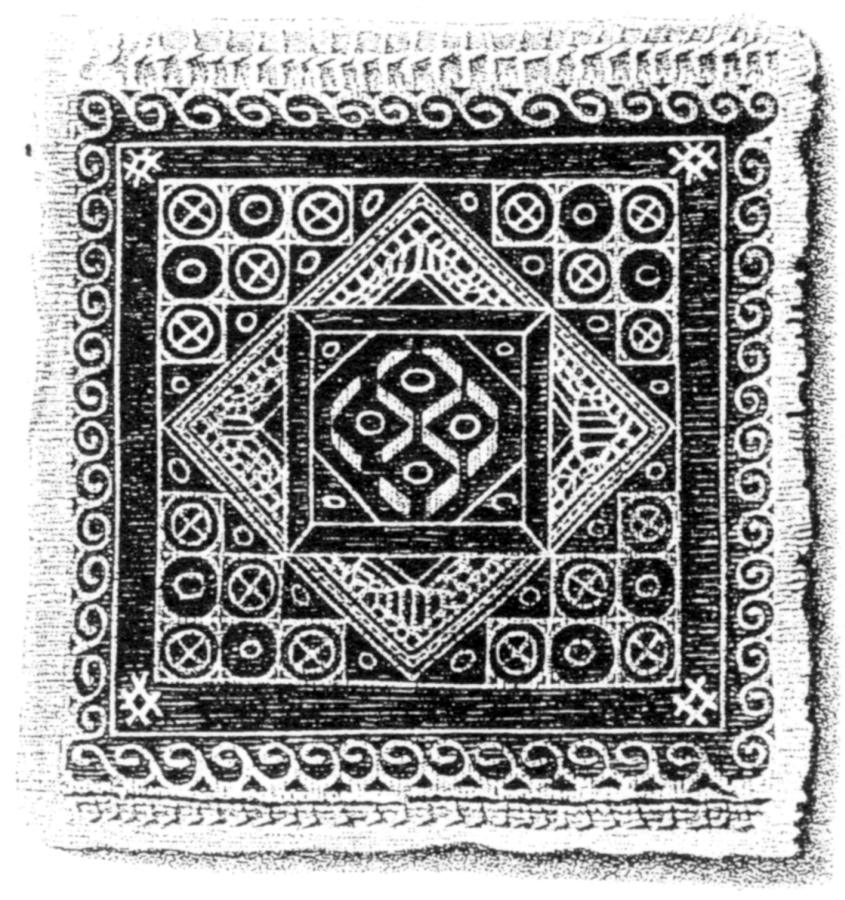

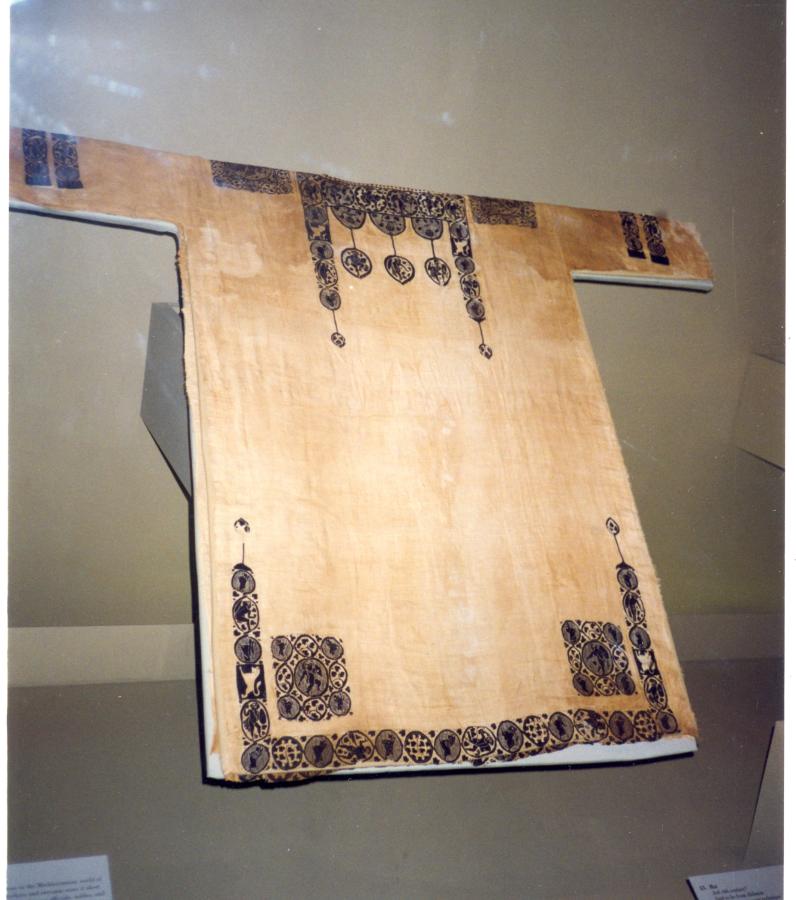

In fig. 19.153 we see an "ancient" Egyptian shirt found in the Memphis region. It is adorned with an ornament; a close-in of said ornament's fragment can be seen in fig. 19.154. This ornament is known to be Slavic. At the centre we see a cross surrounded by four circles and circumscribed by a square. Apart from that, the embroidery has many Qatar crosses circumscribed by circles. Another "ancient" Pharaoh's shirt with Slavic ornamentation can be seen in fig. 19.155. It is believed that the Christian Qatar crosses originated from Bulgaria, and later propagated all across Europe. See CHRON6 for more details.

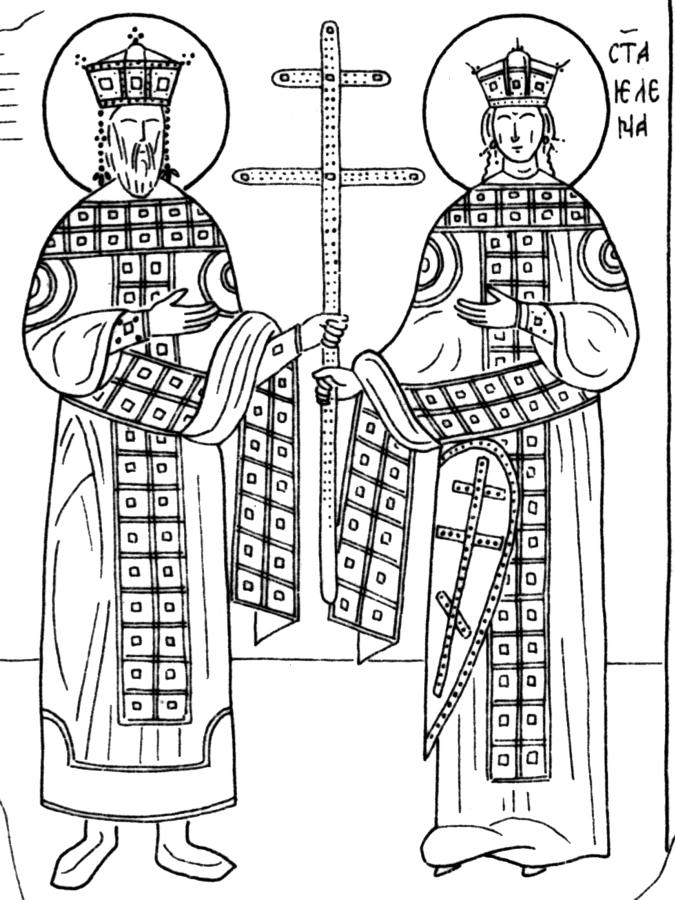

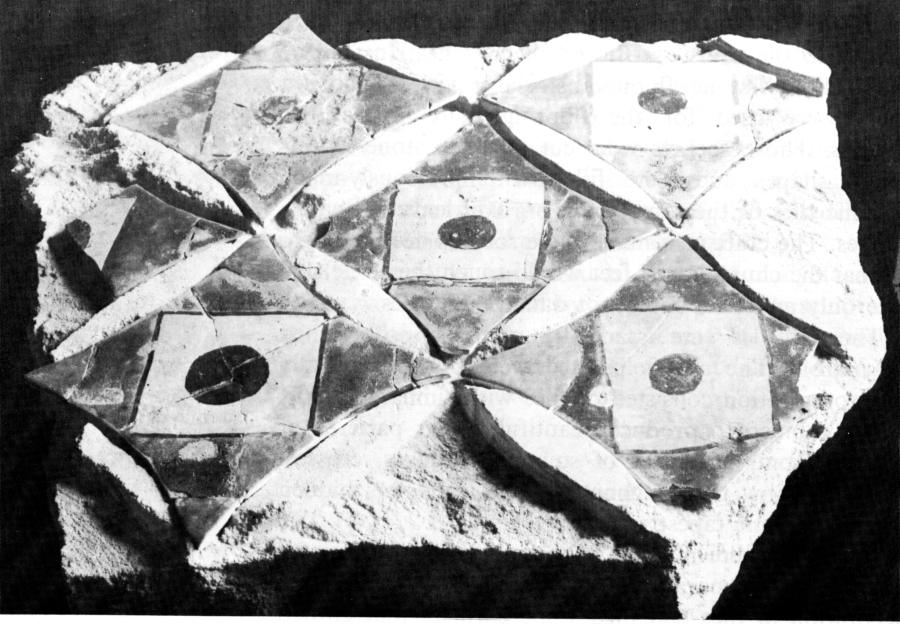

We cite mediaeval Slavic ornaments for comparison in figs. 19.156, 19.157 and 19.158. They were depicted in the mediaeval Serbian frescoes ([276] and the inlays of the ancient Bulgarian capital - Velikiy Preslav ([1411]). One of the most common elements of these ornaments is a cross inside of a square - a straight cross (fig. 19.156) or a slanted cross (figs. 19.157 and 19.158) surrounded by four marks - usually circles or dots. The same ornament can be seen in the centre of the "ancient" Egyptian embroidery.

Our reconstruction explains the Slavic attire of the "ancient" Egyptian mummies perfectly well - Egypt was the graveyard of the rulers and high ranking officials of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire, whose ethnic origins were Slavic and Turkic.

Finally, let us discuss the issue of the general style of the "ancient" Egyptian funereal artwork. It seems unique and quite different from what we see in Europe and in Russia. At the same time, our reconstruction demonstrates that Egypt was the royal graveyard of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire. How could this be? Why does the style of the mediaeval Russian sepulchres differ from the Egyptian? We believe the explanation to be as follows. Egypt must have been the ancient ancestral graveyard of the Czars. It was guarded well, and no trespassers were allowed. Therefore, a unique school of decorative art evolved there. The distinctly abstract character of the "ancient" Egyptian artwork can be partially explained by the fact that the Egyptian artists who decorated the royal tombs appear to have lived a secluded life, almost without any contacts with the outside world. The Valley of the Craftsmen is located near the Valley of the Kings, with ruins of an old settlement still intact. The residents of this settlement were the builders and the decorators of the royal tombs. It was a monastery in every sense of the word. There isn't a single tree in these parts - nothing but sand, rocks and stones. Food for the monks was delivered from afar. One gets the impression that many of the things depicted by the monastic artists were only familiar to them by hearsay; they didn't actively participate in the events reflected in their artwork. This must have resulted in the formation of the characteristic abstract style of the Egyptian funereal artwork.

It has to be noted that the Egyptian artwork is often rather frivolous, with many phallic symbols. This may also be explained that the artwork in question wasn't meant to be seen by the general public - only a narrow circle of the initiated. Only the members of the royal family came here, as well as certain high-ranking associates. It was virtually impossible for a stranger to reach Luxor (the Bight of the Kings) - the Nile was easy to guard, and the road across the desert was all but unreal.