Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 20.

Pharaoh Thutmos III the Conqueror as the Ottoman = Ataman Mehmet II, a conqueror from the XV century.

We continue our motion forward in time following the history of the "ancient" Egypt and approach the epoch of the famous conqueror Thutmos, or Thutmos III. According to our reconstruction, this is already the XV century of the new era - a few millennia later than it is assumed in Scaligerian chronology. Apparently, this new dating can also be obtained with the aid of the independent astronomical method.

1. The astronomical dating of the reign of Thutmos III by the zodiacs of Dendera concurs with the New Chronology of Egypt.

The famous Temple of Dendera contains inscription that allowed the Egyptologists to estimate that it was built by Pharaoh Thutmos III ([99], pages 774 and 776). Brugsch cites the following translation of this inscription:

"The great foundation of [the temple in] Dendera, the reconstruction of the memorial building endeavoured by King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of Both Lands, Ra-Men-Kheper [or Men-Kheper-Ra], son of the Sun, crowned monarch Thutmos [the Third] after the finding of this [presumably, the plan of the temple to be - Auth.] in the ancient writings from the times of King Khufu" ([99], page 776).

We see Thutmos III refer to King Khufu (Cheops) in the traditional pronunciation - the Khut or the Goth, in other words. Therefore, it appears that the Great Sphinx and the Great Pyramids were built before the Temple of Dendera. This order corresponds to the one that is customary for the Scaligerian chronology. The New Chronology yields the same order, which means that it is probably correct.

Another version of the "ancient" Egyptian legend of the construction of the Dendera Temple is as follows: "King Thutmos III ordered to erect this building [to erect and not to reconstruct - Auth.] in memory of his mother, the goddess Hathor, Lady of Ant (Tentira)" ([99], page 375).

We have the unique opportunity to estimate the lifetime of Thutmos III or his immediate predecessors, namely, Thutmos II and Thutmos I. The inscription cited above tells us nothing about the "number" of Thutmos. The arbitrary number enclosed in parentheses is an invention of the Egyptologists.

Let us remind the reader that the ceiling of the Dendera Temple is adorned with two graphical representations related to astronomy - the Round and the Long Zodiac, which demonstrate the planetary dispositions in constellations. These zodiacs can be dated astronomically; all of the above is related in detail in CHRON3, Part 2.

It turns out that a single precise astronomical solution exists for the Round Zodiac - namely, 1185 A. D. There is also a precise astronomical solution for the Long Zodiac of Dendera, and it is unique as well - 1168 A. D. Therefore, both Dendera Zodiacs date from the XII century A. D.

Therefore, Pharaoh Thutmos, who was involved in the reconstruction of the Dendera Temple, must have lived in the XII century A. D. the earliest. This is in good correspondence with the dating of the Thutmos epoch that we suggest - the XV century A. D.

As we have pointed out already, our reconstruction suggests that the Temple of Dendera could have been erected in the XV century as a memorial construction to commemorate the 300-year anniversary of some major dynastic event that took place in the XII century. Both anniversary dates, 1165 and 1185, were recorded in its zodiacs.

Incidentally, the Ataman = Ottoman rulers were called Sultans, whereas the "ancient" Egyptian Pharaohs went by the "Suthen" title ([99], page 5) - which is basically the same as the title of a Sultan, and also "Suthen-Shebt" ([99], page 5), which is once again identifiable as the mediaeval title "Sultan-Shah". The estate of the "royal children" and the "royal grandchildren" was known to the ancient Egyptians under the collective term of Suthen-Reh - in other words, "Sultan Rex", or "Sultan King" ([99], page 85). All of the titles mentioned above are explicitly mediaeval in origin.

2. The great conqueror of the XV century Pharaoh, Sultan and Ataman Thutmos III, also known as Mohammed (Mehmet) II.

Brugsch begins his account of the reign of Thutmos III as follows: "This great ruler, whose reign lasted almost 54 years . . . has left a whole multitude of monuments, starting with the vast temple and ending with a tiny scarab effigy with the name of Thutmos III inscribed upon it - the documents left from this reign are truly countless . . .

The ruler wages war against the strongest kingdoms of the epoch, and victoriously reaches the faraway borders of the world known in that epoch . . . We shall yet be amazed by the accumulated riches that poured into the Pharaoh's treasury . . .

The chronicles of wars waged by Thutmos III are transcribed as holy symbols on the internal part of the walls . . . All these walls have long been destroyed, pillaged and taken apart into stones; only brief fragments of what used to be long lines of text have survived on the pieces of walls that remain intact; however, even those suffice for a general reconstruction of the glorious chronicle wherein the victories of Thutmos were written and getting a basic idea of the enormous distances that he had covered together with his troops.

Over the course of twenty years, the great Pharaoh launched more than thirteen campaigns against foreign nations" ([99], page 302).

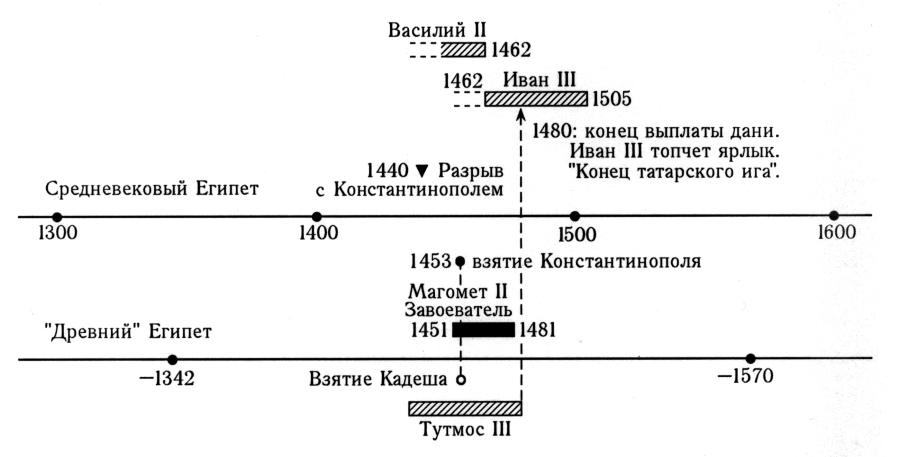

Our reconstruction suggests the following identification. The Ottoman = Ataman conquest started in the XV century. It continued until the end of the XVI century. Apparently, the "ancient" Egyptian chronicles describe it as the conquests of Thutmos, who might be a collective image, primarily based on the famous Mohammed II the Conqueror, also known as Sultan Mehmet II, regnant in 1451-1481 A. D. ([797], page 797). An ancient portrait of Mehmet II can be seen in fig. 20.1.

3. The capture of Kadesh = Czar-Grad by Pharaoh (Ataman) Thutmos in 1453.

One of the main events that took place during the reign of Pharaoh Thutmos III was the capture of the city of Kadesh ([99], pages 306-308). Above, in our analysis of the biography of Ramses II, we already identified the city of Kadesh as mentioned in the "ancient" Egyptian chronicles as Czar-Grad. After the Trojan War of the XIII century Czar-Grad remained the capital of Byzantium for a short while, although it was already controlled by Russia, or the Horde, and the Ottoman = Ataman Empire in the XIV-XV century.

4. Relations between Russia, or the Horde, and the Ottoman = Ataman Empire in the XV century: two parts of the Great Empire.

We shall briefly relate the history of this period in its Scaligerian version, which is correct, in a way, yet in need of a serious rethinking. In order to understand the events in question one must simply retain the awareness that Czar-Grad was already controlled by Russia and the Ottomans in the XIV-XV century, as we have already mentioned, yet strived to regain some degree of independence.

Apparently, in the beginning of the XV century Constantinople swayed towards siding with the West European vicegerents of the Horde, and its rulers entered a union with the Western affiliate of the "Mongolian" Authority - Vatican (named after Batu-Khan) in the newly founded Italian Rome. Scaligerian history describes this event somewhat distortedly - as the recognition of the Italian Catholic Pope's supremacy by the Byzantine Church at the famous Council of Ferrara and Florence of the alleged years 1438-1439, qv above.

As a result, the relations between Constantinople and the Horde, or Russia, and the Ottomans (or Atamans) were severed immediately, since, according to our reconstruction, Islam had still been one with the Orthodox Christianity as practised in the Empire - the religious schism between the Horde and the Ottomans took place somewhat later.

Having strained the relations with the Imperial capital, Czar-Grad automatically sealed its fate, having made its fall imminent. 14 years later, in 1453, it was taken by Mehmet II, whose troops included Russians, as we demonstrate in CHRON4. The participation of Russian troops in the storm of Constantinople is a hypothesis of ours, since every trace of this event was wiped out from Russian history by the Romanovian historians with the utmost diligence. Nevertheless, the information that we have at our disposal allows us to regard said fact as definite (see CHRON4).

The fall of Czar-Grad, or the Byzantine Rome, is a crucial event in the history of the Great = Mongolian Empire. Our reconstruction of the ensuing events is as follows (see fig. 20.2).

The Russians and the Ottomans regarded the capture of Czar-Grad as the final sanctification of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire by the authority of the Evangelical Jerusalem = Czar-Grad = Troy - the city where Jesus Christ (Andronicus-Christ 1152-1185) lived and was crucified finally became part of the Empire and somehow passed on its primary Christian halidoms as well as its supreme ecclesiastical authority.

As a result, Russia (or the Horde) remained the key military and administrative centre of the "Mongolian" Empire, whereas the Ottoman = Ataman Empire became the proud owner of Jerusalem, the city described in the Gospels, or Troy (Trinity).

Two centres have emerged as a result; the dissension between the Horde and the started to grow as a result. This situation obviously led to the important and awkward issue of supremacy within the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, which was still a united state. There were two contestants to the throne – Ataman Sultan Mehmet II and the Great Czar, or Khan of Russia Ivan III (or, alternatively, Vassily II). It is believed that Vassily was already blinded by that time, and so Ivan III was the de facto ruler.

However, since Czar-Grad (Jerusalem), the holy city of Christ, had ended up in the possession of Mehmet II, this gave the latter formal priority, which ended in 1481, the year of his death. The spiritual leadership was an arbitrary matter and didn’t stem from the real balance of military power within the Great = “Mongolian” Empire. As we have seen, the military supremacy of Russia, or the Horde (also known as Israel) was overwhelming during the epoch in question.

As soon as Mehmet II died, in 1481, Ivan III publicly declared about his refusal to obey Czar-Grad in any way at all, even formally. This was the first discordance within the Great “Mongolian” Empire, which is when the Muscovites made their claim about Moscow being the Third Rome (see CHRON5, Chapter 12:9). The budding religious dissent must have flowered shortly.

Issues of subordination translated into taxation in the Great = “Mongolian” Empire. The sum was an altogether different issue – loyal subjects paid a small tax, which could be returned to them as fees (mind the words of the Chinese Khan’s state official as cited in CHRON5, Part 2: “China”). Faraway conquered lands paid real tax, of course.

Nevertheless, the very fact of taxation was a symbol of subordination within the Empire – for loyal subjects and conquered lands alike. The party paying the tax recognized itself as subordinate to the party receiving it. This was a rule of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire.

Therefore, the temporary recognition of the Evangelical Jerusalem’s supremacy by Russia, or the Horde, for a period of 30 years (between 1453 and 1481) must have been expressed as the payment of some tribute to the City of Christ, possibly of a purely symbolic nature.

Therefore, the famous refusal of Ivan III to pay tax in 1480 must have meant that Russia (the Horde) declared itself unwilling to recognize Czar-Grad as its ecclesiastical capital, which was expressed in the famous formula about Moscow being the Third Rome.

In the consensual “Romanovian” rendition of the Russian history the fact that Russia was paying a symbolic tribute to the Ottomana = Atamans during those thirty years transformed into the “tragic three hundred years of slavery” suffered by the Russian nation under the yoke of the monstrous Tartar invaders, whereas the refusal of Ivan III to pay tribute was interpreted by the Romanovian historians as “the end of the Great Tartar Yoke in Russia”.

One must think, Ivan III would be greatly surprised to learn how his epoch would be described a mere 200 years later by Tatishchev, Miller, Bayer, Schlezer, Karamzin, Klyuchevskiy, Solovyov and other “specialists in the field of Russian history”.

Let us however return to the XV century. The above sequence of events was perfectly natural. Both Czar-Grad and Moscow were capitals of two enormous parts of the Great Empire. The temporary prevalence of Constantinople after 1453 wasn’t that great, and the first event to interfere with the normal flow of things, namely, the death of Mehmet II, put an end to this prevalence immediately.

This explains the oddities inherent in the Millerian and Romanovian rendition of “the end of the Tartar Yoke in Russia”, which falls over precisely this year, 1480. It is believed that after the refusal of Ivan III to pay tax the “Russian” and the “Tartar” troops faced each other for battle at River Ugra.

“The troops of the opposing parties stand on either coast of the Ugra, reluctant to engage in battle” (“The Ugra Stand”)” ([942], age 40). This meditative “stand” is declared to have ended the horrendous Tartar yoke – the bloody epoch of foreign rule came to its end peacefully and surreptitiously.

We are of the opinion that everything is perfectly clear. There was no yoke and no reason for the Russians and the Ottomans to engage in battle in 1480. One must be aware that during the epoch of Czar-Grad’s capture Mehmet II and Ivan III (or Vassily II) were allies according to our reconstruction, and possibly friends. Therefore, there were no problems between the allies while Mehmet II was still alive. Ivan III recognized the religious leadership of Mehmet II and paid the symbolic tribute without any qualms – one must also remember that Mehmet II was older than Ivan III.

However, recognizing the superiority of Mehmet II, Ivan III could by no means recognize that of Mehmet’s successor. The accumulating discrepancies – religious, for instance, between Russia, or the Horde, and the Ottomans, have led to certain disputes, but by no means military action – the two parties managed to remain on friendly turns up until the very epoch of the Romanovs.

The pro-Western Romanovs initiated an endlessly long and useless war with Turkey, which diverted Russia from all other affairs for centuries to come and resulted in the dissolution of Turkey.

However, let us once again return to the XV century. The Western Europe, which was conquered by the “Mongols”, or the Great Ones, as early as in the XIV century, was largely controlled by the Horde, or Russia – to a greater extent than by the Ottomans (or Atamans). Apparently, the greater part of the tribute paid by the Westerners went to Russia. Therefore, the Ottomans must have regarded the Western Europe as an integral part of Russia, or the Horde – to the extent of calling it Ruthenia (the Horde, or Russia).

Below we shall see this circumstance reflected in the “ancient” Egyptian chronicles from the epoch of Thutmos, which date from the second part of the XV century in reality. The Egyptian chronicles of stone use the word Ruthenia, or Russia, for referring to the whole of Europe, the East and the West alike. The fact that Ruthenia was a mediaeval name of Russia is mentioned in [517] and in Part 6 of the present work.

Also, one has to keep in mind that the same Great = “Mongolian” (primarily Russian) conquest of the XIV century resulted in the transfer of many Russian names to the territory of the Western Europe.

We shall simply cite a single example that we believe to be vivid enough – the name Ruthenia transforming into Luthenia (R -- L), or Latinia (Italy in reverse: TL = LT). The Etruscans were the ones who brought the Russian names to Italy in the XIII-XIV century, among them – the name Ruthenia, which has eventually become Latinia and then Italy. Therefore, every time we see Ruthenia, or Latinia, mentioned in the stone chronicles of the “ancient” Egyptians, we must find out which country was referred to exactly – Russia, Italy, Prussia etc.

Our final comment is as follows. We may never have managed to reconstruct and understand the XV century history if we weren’t suddenly helped by the history of the “ancient” Egypt, or the stone chronicles of the pyramid land, transferred into the distant past by the Scaligerian “chronology”. As we understand today, the hieroglyphic writings of Egypt in Africa tell us a lot about the history of Europe – and, in particular, the history of Russia. They contain a more or less complete rendition of the XIV-XVII century history, sometimes with amazing details that were either lost elsewhere or destroyed in the creation of the false Scaligerian version.

It was only owing to the fact that the Egyptologists and the Scaligerite historians in general failed to recognize the whole significance and the meaning of the authentic “ancient” Egyptian documents carved in stone, hence their survival despite the endeavours of the hammer and chisel artists.

Western European Scaligerites were a great deal more successful. For instance, we don’t know whether the long lists of items sent to the rulers of the “Mongolian” Empire by their vessels as tribute in the XIV-XVI century have survived anywhere at all. Let us recollect that the vassals were very punctual about the tribute, doing all they could so as not to cross the Sulltan, or Ataman, and the Horde, or Israel (see CHRON5, Chapter 12:3.3). Most likely, no such documents have survived in Europe, the reasons being obvious enough. However, such lists do exist on the walls of the “ancient” Egyptian buildings – and they are very detailed indeed. We shall cover them below.

Now let us go over the “ancient” Egyptian chronicles carved in stone and see what they tell us about the events of the XIV-XVII (or even the XVIII) century.